The most common causes of acute hepatitis are alcohol and hepatotropic viruses. However, other much less common infectious agents can also cause acute hepatitis in the context of systemic diseases. We present the case of a patient diagnosed with secondary syphilis with hepatic involvement.

This was a 26-year-old homosexual male with no relevant previous medical history. He went to Accident and Emergency with a two-week history of asthenia, epigastric pain, pharyngeal discomfort and mucocutaneous jaundice. His regular partner had been diagnosed with syphilis two months earlier, so the patient had also had serology for Treponema pallidum at that time, which was negative. He reported no fever, altered bowel habit, recent travel, contact with small children, tattoos or previous transfusions, use of potentially hepatotoxic substances or ingestion of spoiled food.

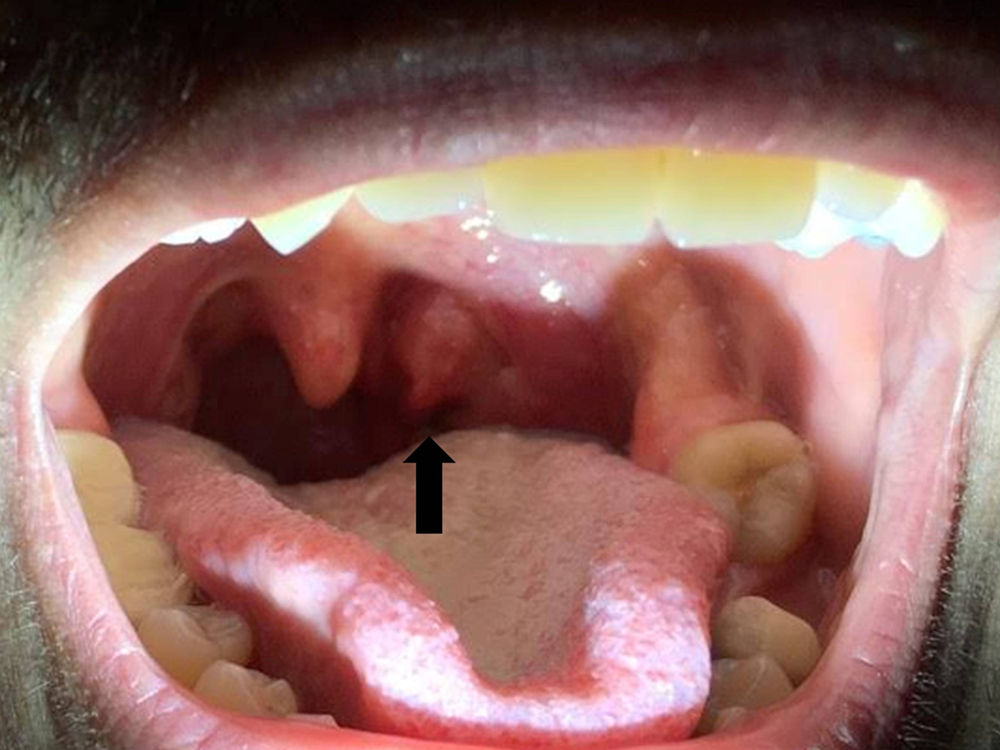

On physical examination, an ulcer was found on the left tonsil with a blackish fibrinous base (Fig. 1), in addition to jaundice. There were no signs of lymphadenopathy, skin lesions, genital lesions or neurological alterations.

Blood tests showed abnormal liver function tests, predominantly with cholestasis [aspartate aminotransferase (AST): 176IU/l; alanine aminotransferase (ALT): 371IU/l; gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT): 540IU/l; alkaline phosphatase (AP): 1032IU/l; and total bilirubin of 7.9mg/dl] with complete blood count, coagulation and other basic clinical biochemistry normal. Abdominal ultrasound showed no abnormal findings.

One month before attending Accident and Emergency, the patient had been assessed in Hepatology Outpatients for non-specific malaise with slight elevation of transaminases, and a full investigation for liver disease was requested. Serology for common hepatotropic viruses (hepatitis A, B, C and E) as well as HIV, autoimmunity (ANA, AMA, anti-LKM and smooth muscle antibodies), iron profile, ceruloplasmin and alpha-1 AT were all negative. Serology for syphilis was repeated, resulting in positive IgG, rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test 1/32 and positive T. pallidum haemagglutination assay (TPHA). A sample was taken of the ulcer on the left tonsil, interpreted as syphilitic chancre, with T. pallidum confirmed in the genome amplification.

As secondary syphilis with hepatic involvement was suspected, treatment was prescribed with penicillin G benzathine. The patient made good progress, with improvement both clinically and analytically.

Syphilis is a sexually or vertically transmitted disease caused by the spirochete T. pallidum. Syphilitic liver involvement is very uncommon (<1% of cases) and can occur in the secondary or tertiary phase of disease1 due to multiplication and haematogenous spread of the spirochete to the liver.2 In the secondary syphilis phase, cholestasis occurs, with a characteristic elevation of alkaline phosphatase; this is usually accompanied by pyrexia, the typical palmoplantar rash and even nephrotic syndrome, although all three signs do not always have to be present.3 In the tertiary phase, the characteristic lesions are syphilitic gummas, most common in the right lobe of the liver and generally asymptomatic, unless they cause compression leading to Budd–Chiari syndrome.4

The diagnosis can be established in the presence of abnormal liver function tests, positive serology and improvement after antibiotic treatment.5 The liver biopsy findings are not pathognomonic (periportal necrosis, endotheliitis, cholangitis or pericholangitis) unless the spirochete is detected in the hepatic lobule, which is very uncommon.6 Therefore, although some authors consider it advisable to perform a liver biopsy for the definitive diagnosis,7 it does not seem to be essential. In most of the patients described in the literature, syphilis coexists with other sexually transmitted diseases (HBV, HCV, HIV, etc.),2 so it has to be taken into account that finding one cause of liver disease does not exclude others.

The treatment of syphilitic hepatitis consists of administration of penicillin G benzathine, or doxycycline or macrolides in the case of allergy to beta-lactams.8 In the second week of treatment, jaundice (an idiosyncratic reaction known as Jarisch–Herxheimer) with uncertain pathophysiology may develop,8 but it clears up without sequelae in virtually all cases.

In our patient, liver involvement represented an unusual manifestation of secondary syphilis, as no pyrexia, palmoplantar rash or nephrotic syndrome were detected. Nor did he have any other concomitant sexually transmitted disease. The previous epidemiological history in his partner (not revealed initially by the patient), the cholestasis with elevation of alkaline phosphatase and, finally, the positive serology, pointed to the diagnosis. The atypical location of the syphilitic chancre on the tonsil was interesting and confirms the importance of a thorough history and physical examination. As the genome amplification was positive for T. pallidum and the patient had an excellent response to the antibiotic treatment, liver biopsy was not considered necessary.

In conclusion, liver dysfunction related to secondary syphilis is an uncommon occurrence, but should be suspected in at-risk patients. Liver biopsy is not considered essential for diagnosis in all cases. In the majority of patients, the outcome is excellent once they start treatment with penicillin G benzathine.

Please cite this article as: Honrubia-López R, Rueda-García JL, Burgos-García A, Fernández-Martos R, Mora-Sanz P. Hepatitis aguda como manifestación de sífilis secundaria. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:505–506.