Proton-pump inhibitors (PPI) are among the most widely used drugs worldwide, and specifically in Spain.1 They are well tolerated, but in recent years have been linked to various infrequent but potentially serious adverse effects, such as: calcium, magnesium and vitamin B12 deficiency, Clostridium difficile infection, pneumonia, increased risk of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients, as well as acute interstitial nephritis (AIN), the prevalence of which appears to be increasing in the elderly population.2,3

We report the case of a 42-year-old man, single kidney from birth, who was admitted to the nephrology service for acute deterioration of kidney function. He reported flu-like symptoms lasting 10–15 days. He had recently taken NSAIDs (ibuprofen 600mg/8h for 5–7 days) in combination with omeprazole 20mg/day. He presented no symptoms suggestive of systemic disease/glomerulonephritis, only polyuria and polydipsia. The physical examination was unremarkable. Laboratory tests showed creatinine: 2.8mg/dL (0.6–1.19) and urea: 65.3mg/dL (10–50), high (57) ESR (0–10) and mild eosinophilia 4.9% (0–4). Mild leukocytosis. Other studies (immunology, serology, microbiology and ultrasound) were normal. We suspected a drug aetiology, so potentially nephrotoxic drugs were suspended. Given the deterioration of kidney function and high suspicion of drug-related AIN, empirical treatment was started with prednisone 40mg/day for 2 weeks, and then tapered slowly.

The patient made good progress, with recovery of kidney function 1 month after starting corticosteroid therapy.

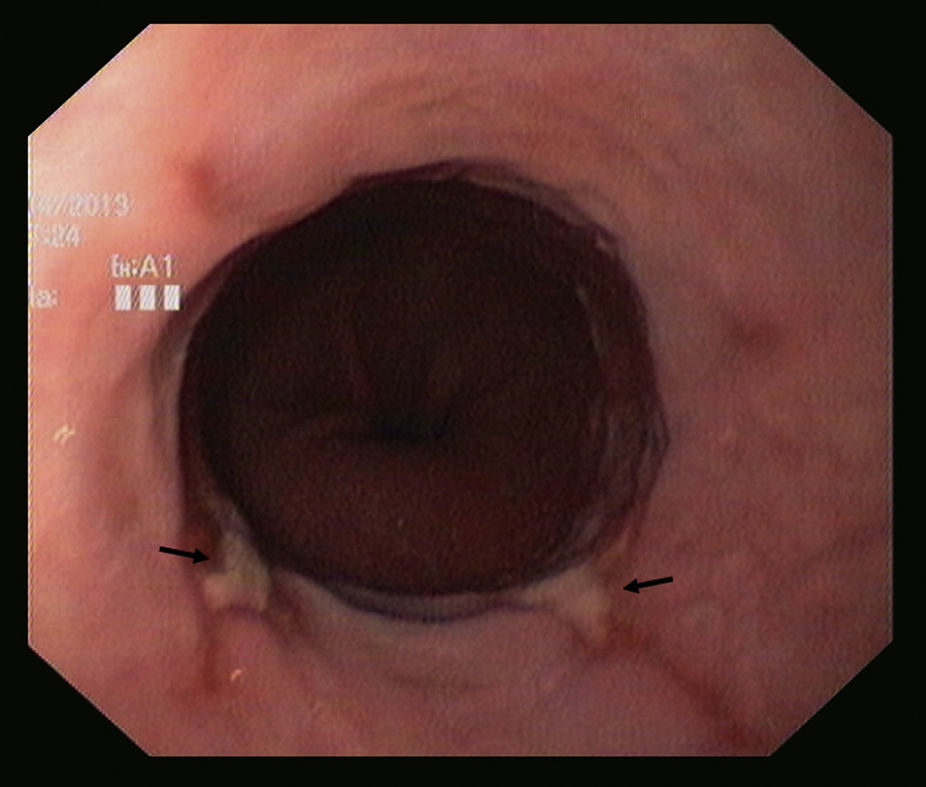

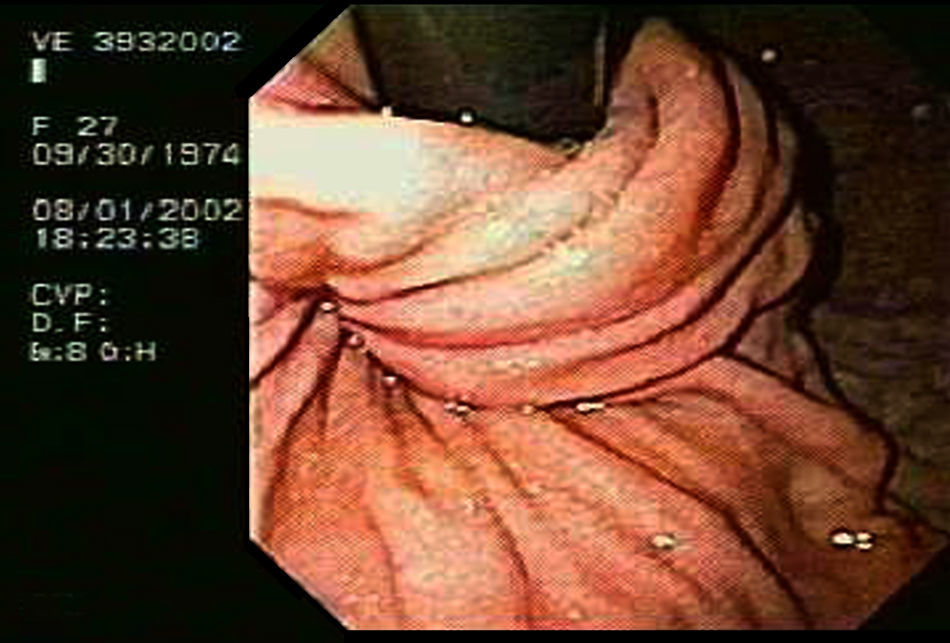

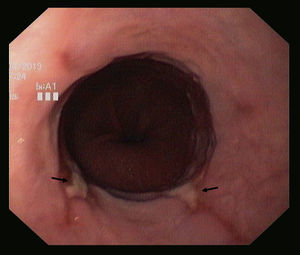

Five years later, following typical reflux symptoms, his primary care physician prescribed ranitidine 300mg and requested a gastroscopy, which showed a 4cm hiatal hernia and grade B oesophagitis, according to the Los Angeles classification system (Fig. 1). Symptoms persisted, so he was given lansoprazole 30mg/day and made good progress. However, 2 weeks after starting treatment impaired kidney function was observed: creatinine 2.7mg/dL and urea 63mg/dL. Lansoprazole was suspended and corticoid steroids were again prescribed, confirming the suspicion of proton-pump inhibitor induced AIN. He was referred to the gastroenterologist for assessment and a decision on which therapy to use. As PPI therapy was contraindicated due to serious adverse effects, and pathological acid reflux was confirmed with manometry and pH-metry, he was referred for surgery and underwent Nissen fundoplication. His clinical course was satisfactory, and he is currently asymptomatic (Fig. 2).

PPIs are often prescribed for indications that are not approved or clinically recommended.4 Despite this, it is important to bear in mind their potential adverse effects. Clinical suspicion of AIN is low, making it one the most serious and hard to diagnose of all adverse reactions.5 Interstitial nephritis is characterized by inflammatory infiltrate in the tubules and/or the interstitium of the kidney. Clinically, it takes two forms: acute and chronic. The acute form is associated with acute kidney injury (AKI), while in the chronic forms the clinical picture is less clear. AIN can be classified according to aetiology: drugs and toxic substances (most common), infectious, associated with systemic disease, idiopathic, neoplastic and metabolic disorders. Another clinical picture that must be considered in the differential diagnosis of AIN is atheroembolic renal disease, especially in the elderly.6

The drugs most commonly associated with this entity have so far been NSAIDs and antibiotics. However, a growing number of cases of AIN associated with PPI use have been published in recent years, and now these drugs, together with NSAIDs, are considered most commonly implicated in AIN.7 In addition, the clinical presentation of drug-induced NIA has changed, and now the standard fever, rash and eosinophilia triad is uncommon. In a review of over 150 cases, one of these symptoms was identified in 50% of patients, but all three in fewer than 5%.8

Histology is not necessary for the diagnosis of AIN if there is well-founded suspicion and potential causative agents can be removed.

The role of steroids in the treatment of drug-induced AIN has long been a subject of debate. At present, despite the absence of prospective randomized studies, it is accepted that steroid treatment is indicated and should begin immediately after diagnosis in order to reduce the risk of chronic kidney failure.9

It is sometimes difficult to identify the trigger drug in AIN, and re-exposure to the probable causative agent is not ethically justified. In our case, re-exposure enabled us to quickly establish the aetiologic diagnosis.

In patients with a high suspicion of AIN, guidelines recommend suspending all PPIs. The most effective alternative treatment of acid reflux in these patients would be an H2 blocker, although evidence has shown these to be far less successful than PPIs in controlling symptoms, complications and relapse. Ideally, if patients can be screened for predictors of successful surgical outcome, total or partial fundoplication would be equally or even more effective than PPIs.

The most common indications for anti-gastroesophageal reflux surgery include: (a) need for maintenance medical treatment, mainly in young patients, (b) resistance to PPIs, and (c) uncontrollable complications. Fundoplication is also indicated in patients contraindicated for PPI therapy due to severe adverse effects.

In conclusion, PPIs are widely used in clinical practice, and have a good risk/benefit profile. However, given their potential for toxicity, they should be carefully prescribed and the duration of treatment should be controlled.

Please cite this article as: Ruiz-Clavijo García D, Zúñiga Ripa A, González de la Higuera Carnicer B, Valdivielso Cortazar E, Bolado Concejo F, Urman Fernández J, et al. Nefritis intersticial aguda inducida por inhibidores de la bomba de protones: indicación poco frecuente de cirugía antirreflujo. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:87–88.