Abdominal pain is one of the most common reasons for visits to emergency departments and to gastroenterology departments. Differential diagnosis represents a major challenge, given the wide array of clinical entities that can cause abdominal pain, some of which have an unfavourable prognosis. In some cohorts, a specific diagnosis was ultimately not made in more than 30% of cases.1,2

We report the case of a 40-year-old man, an active smoker for more than the past 20 years, with no personal or family history of note, apart from closed abdominal trauma four years earlier, and not on regular drug treatment. He presented with constant epigastric abdominal pain radiating towards both hypochondriac regions with an onset eight hours earlier. He had no associated jaundice of the skin or mucous membranes, choluria or acholia; he also had no nausea or vomiting and no alterations in the frequency or characteristics of his bowel movements. He did not have a fever, constitutional syndrome or any other associated symptoms.

Physical examination revealed pain on epigastric palpation, without signs of peritoneal irritation and with preserved peristalsis and distal pulses. He also had no signs of collagenopathy. As an initial approach to diagnosis, blood tests were performed; the only notable findings were slight liver panel abnormalities (aspartate aminotransferase [AST] 66 U/l, alanine aminotransferase [ALT] 58 U/l, gamma-glutamyl transferase [GGT] 106 U/l and alkaline phosphatase [ALP] 76 U/l); blood amylase levels, kidney function, electrolytes and complete blood count values were normal. Given the findings observed, an emergency abdominal ultrasound was ordered and detected a hypoechoic periportal mass, causing stenosis of the portal vein and extending to the uncinate process. No cholelithiasis, bile duct dilation or other significant abnormalities were seen.

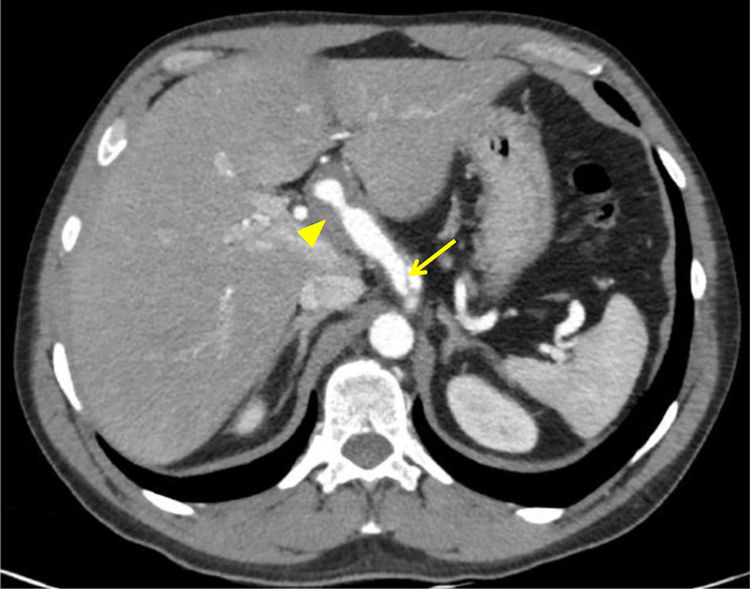

Therefore, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis was performed to conduct a detailed investigation of the ultrasound findings and complete the extension study. This found an “intimal flap” suggestive of coeliac trunk dissection extending to the hepatic artery with pseudoaneurysm of that artery, as well as dissection of the middle third of the superior mesenteric artery, with no aortic involvement (Fig. 1). No abnormalities were seen in the liver or in the biliopancreatic area.

In light of these findings, the angiology and vascular surgery departments were contacted and a decision was made to have the patient undergo elective surgery with hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm ligation and aorto-hepatic bypass with autologous right saphenous vein grafting. The patient was clinically and haemodynamically stable at all times and followed a satisfactory course in the postoperative period and thereafter. Acetylsalicylic acid was added as maintenance treatment.

Coeliac trunk dissection is an uncommon cause of abdominal pain, but a significant one due to its prognostic implications. On the one hand, it is important to distinguish cases with associated aortic dissection given its implications for treatment. On the other hand, it is necessary to identify certain associated risk factors, such as being a middle-aged man and having high blood pressure, trauma, collagen disease or iatrogenesis. In this case, despite the patient’s history of trauma four years earlier, the possibility that arterial dissection was an incidental finding in the study of abdominal pain of another origin cannot be ruled out.3,4

Regarding diagnosis, CT angiography is the most widely used technique, with the “intimal flap” and the thrombosed false lumen being more common findings of note. Doppler ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging and arteriography may also be useful. Regarding treatment, early surgery is required in cases of intra-abdominal bleeding or significant organ damage secondary to insufficient perfusion. Aorto-hepatic bypass has yielded good outcomes; however, stent placement has also shown favourable results. Nevertheless, the current trend is towards medical treatment in most cases, including fluid therapy, a strict diet, antihypertensive agents, antiplatelet agents and/or anticoagulants. Some studies have shown that antihypertensive agents do not modify the natural course of the disease. As for antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants, there are no clearly defined indications for their use. This option is reasonable if the patient is stable and has no warning signs and symptoms, with periodic follow-up CT scans to monitor the patient for ischaemia.4,5

In conclusion, the treatment to be used must be personalised depending on the patient’s characteristics, since, given the low frequency of the disease, there are no studies of a sufficient size to issue solid recommendations in this regard.5

FundingNo funding or grants were received for the conduct of the study.

Please cite this article as: Martínez-Domínguez SJ, Borao Laguna C, Saura Blasco N, Hernández Ainsa M, García Mateo S, Velamazán Sandalinas R, et al. Aproximación al manejo de la disección del tronco celíaco. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;45:137–138.