Acute liver failure (ALF) is an uncommon syndrome due to severe deterioration of liver cell function that may require an emergency liver transplantation (ETx). Clinical signs include a decrease in prothrombin index (PI) (<40%) and hepatic encephalopathy. Severe ALF can be fulminant when it appears within <2 weeks of clinical onset or subfulminant if it appears within 2–8 weeks.1 In Spain, approximately one third of ALF cases are due to hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, although around 5% are due to autoimmune hepatitis (AIH). This figure, however, is underestimated since cases caused by non-classical phenotype AIH are classified as cryptogenic ALF.

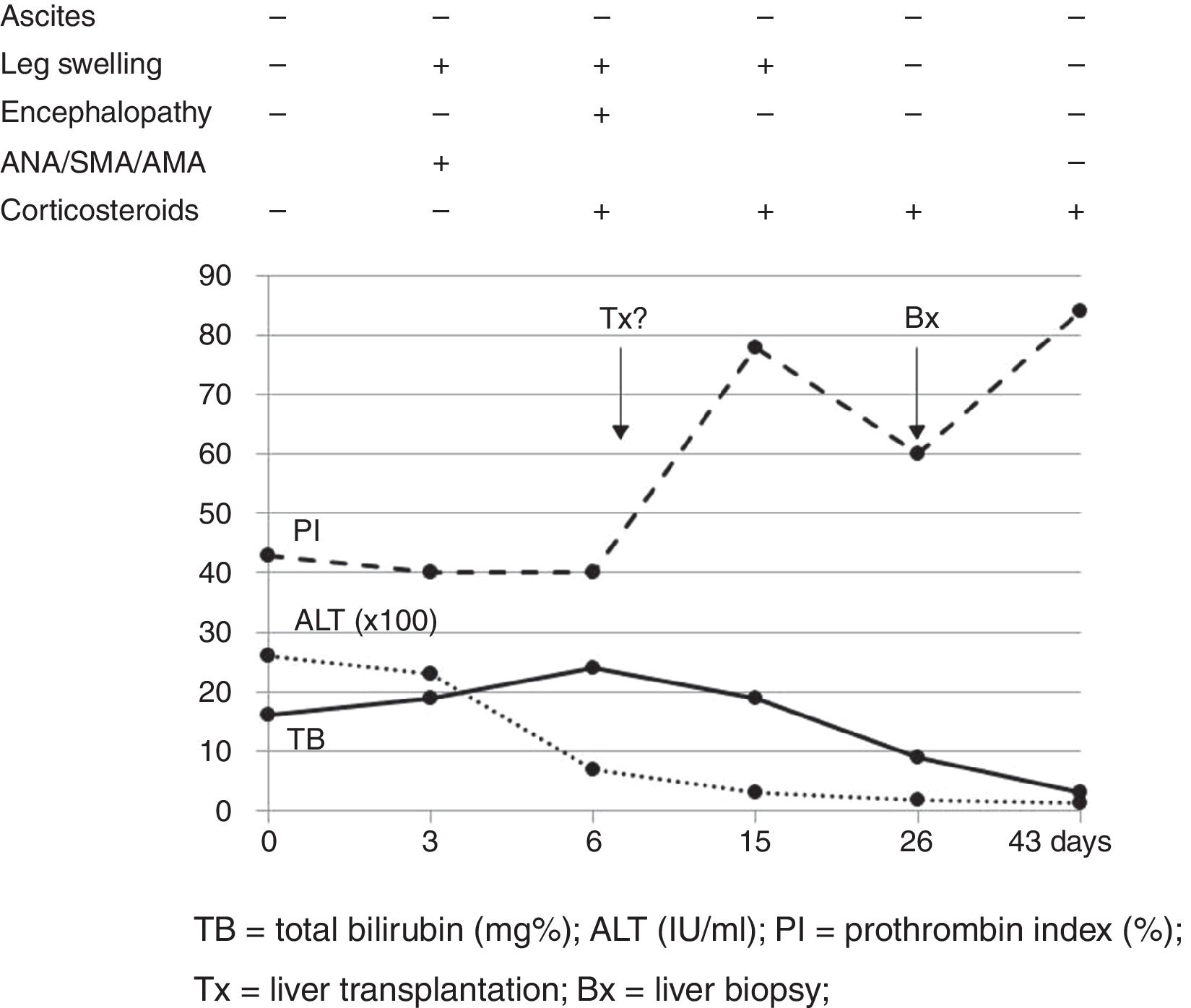

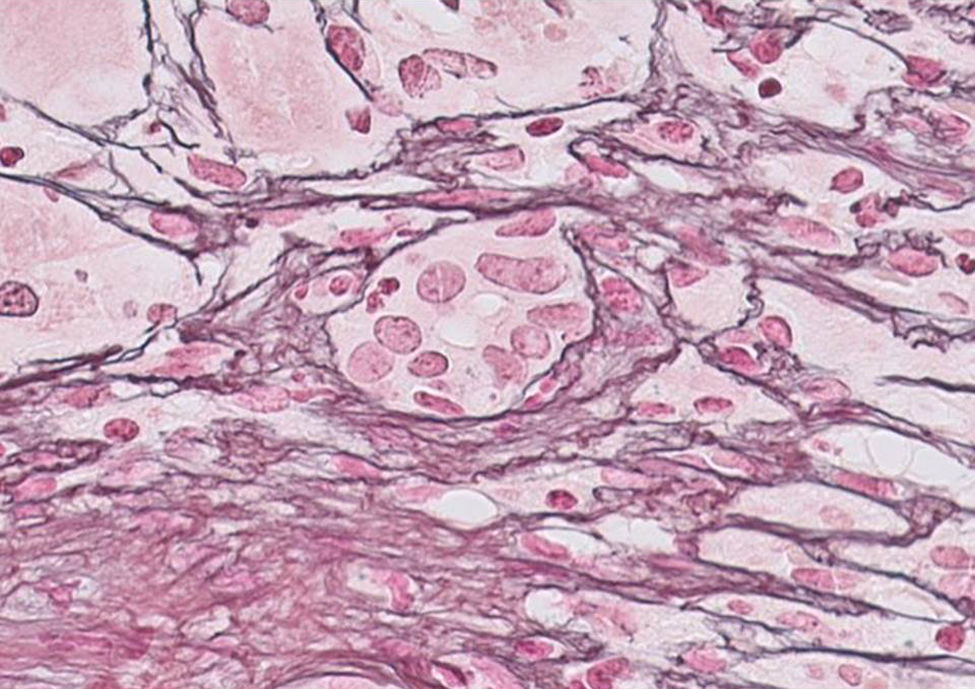

Our case study is a 29-year-old female patient, with no significant medical history, who was 20 weeks pregnant. She was referred to the hospital after suffering from jaundice and choluria for 2 days. She had no risk factors for hepatic diseases and said she had not travelled recently or consumed any drugs/hepatotoxic substances. She had yellow discolouration of the skin and sclera (jaundice) but was alert and oriented and had no asterixis. At admission, her lab test results were: AST 3205IU/ml, ALT 2664IU/ml, direct bilirubin 12.9mg%, indirect bilirubin 3.1mg%, leukocytes 13,820/mm3, INR 1.91 and PI 43% (Fig. 1). The Doppler ultrasound was normal. The Obstetrics department confirmed it was a normal pregnancy. Hepatotropic virus results (HAV, HBV, HCV, HDV, HEV, CMV, EBV and herpes simplex) were negative, while autoantibody screen results (ANA-1/320, SMA-1/320 and AMA-1/320 and IgG–IgA–IgM–IgE 1870–235–79–124mg/dl) were positive. Other serological test results (copper, ceruloplasmin and α-1 antitrypsin) were normal. No percutaneous/transjugular liver biopsy (biopsy) was performed due to abnormal clotting and foetal radiation. In accordance with consensus criteria,2–5 a diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis with overlap syndrome (ANA+, AMA+) was considered.6 On day 5, a course of methylprednisolone was started (50mg/24h-IV/10 days followed by a tapering dose regimen). On day 6, the patient deteriorated: malleolar and pretibial oedema, grade II encephalopathy (flapping +), blood pressure 24.2mg%, INR 1.8, PI 40%, factor V 72% and urine sediment normal. Her condition was classified as fulminant ALF with MELD score of 241 (Fig. 1). On day 8, encephalopathy was grade III and the possibility of an ETx was contemplated since 3 of the King's College criteria (non-A, non-B hepatitis; TB>18mg%; and duration of jaundice before onset of encephalopathy >7 days) were met. After 24h, the patient improved (PI 54%, INR 1.5, TB 18.6mg%, AST/ALT 307/665IU/ml), ruling out an ETx. On day 26, once PI had returned to normal, a percutaneous biopsy was performed (Fig. 1): grade 2, stage 2 AIH, “portal inflammation with necrosis of the limiting plate and bridging periportal fibrosis, with destruction of bile ducts and disappearance of interlobular bile ducts” (Fig. 2). On day 43, the patient was discharged with normal obstetric control, almost normal lab test results and tapered doses of corticosteroids+azathioprine (50mg/day). Three days later, she suffered a miscarriage. After 4 months, all lab test results were normal and autoantibody screen results were negative.

AIH presents in episodes, attacking both healthy livers and livers affected by prior flare-ups.3–5 Diagnosis can be difficult when features of the classical phenotype are absent2–4; therefore, the International AIH Group defined several score-based diagnostic criteria,3–5 with liver biopsy results (not pathognomonic) being essential for diagnosis.4 As in our case, AIH sometimes overlaps with primary biliary cholangitis criteria. This overlap syndrome is more a clinical than a histological entity, sharing features of both AIH (predominant phenotype) and cholestasis (Paris and EASL criteria),5,6 and must be interpreted within the context of a systemic autoimmune phenomenon. Only follow-up will determine the direction in which each process will develop.4–6 Almost 6% of AIH cases start out as ALF, requiring differential diagnosis with viral hepatitis, Wilson's disease and α-1 antitrypsin deficiency, in addition to other concomitant or pre-existing hepatic processes associated exclusively with pregnancy (second trimester) (preeclampsia, HELLP, intrahepatic cholestasis and acute fatty liver of pregnancy). The diagnosis of such processes tends to be simple using clinical, analytical and ultrasound data.7–9 A probable diagnosis of AIH is sufficient to be able to start steroid therapy early, with prognosis and the need for ETx depending on early treatment. Our patient was placed on the ETx list but did not actually receive a transplant since her symptoms improved within 48h. The difficulty of personalising the need for ETx using parameters/criteria of varying strictness5,10 due to the presence of false negatives and positives (as in our case) has resulted in these criteria being reviewed in multi-centre studies between various ETx units.10 There is a state of immune tolerance during pregnancy due to hyperoestrogenaemia (induces shift from Th1 response to Th2 response or changes in anti-inflammatory cytokine profile).7,8 This may explain spontaneous improvement in some cases of AIH during pregnancy and the appearance of acute episodes towards the end of pregnancy or postpartum once oestrogen levels fall. Prior to modern-day treatments, rates of foetal morbidity and mortality and complications in pregnant women were high.7 Today, pregnancy in a woman with AIH is safe for both the mother and her foetus, provided that she receives proper pre-natal care.7,8 In our case, the patient suffered a miscarriage 3 days after discharge, and it seems reasonable to say that AIH+ALF were responsible for this given that steroid treatment is considered safe during pregnancy. To summarise, a fast differential diagnosis is necessary in the event of acute liver symptoms in pregnant women, when resulting in ALF, along with early immunosuppressant therapy, with prognostic value, even before reaching a definite histological diagnosis.

Please cite this article as: Caballero-Mateos AM, López Garrido MÁ, Becerra Massare P, de Teresa Galván J. Insuficiencia hepática aguda grave (IHAG) fulminante de origen autoinmune en gestante. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:259–260.