The term haemobilia refers to any gastrointestinal bleeding originating from the biliary Tree.1 Its aetiology is quite varied and determines the necessary treatment. Currently, most cases are secondary to accidental or iatrogenic trauma.2 Vascular disorders, such as arterial pseudoaneurysms, are an uncommon cause. This article will look at 2 cases of haemobilia secondary to pseudoaneurysms of the cystic artery, both associated with symptoms of acute cholecystitis.

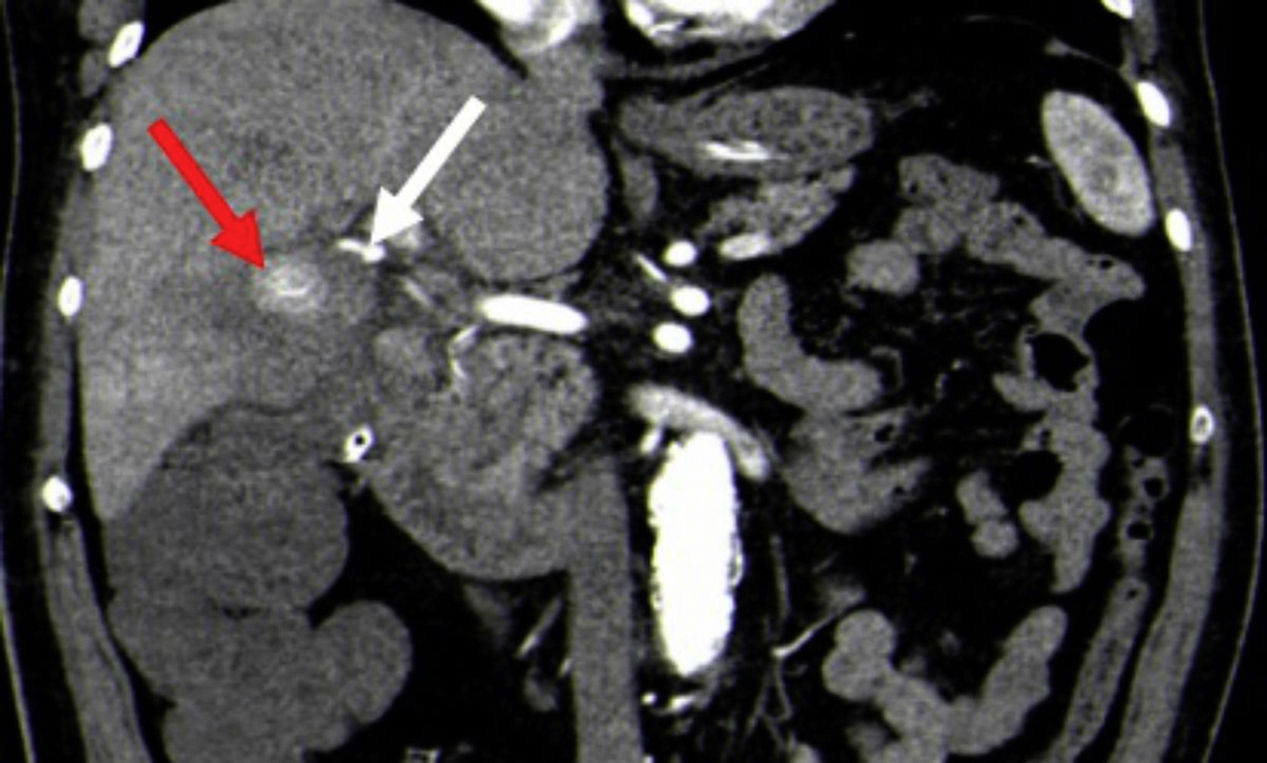

The first case is a 74-year-old male patient with right upper quadrant pain associated with fever, haematemesis and melaena. His lab results showed elevated amylase, lipase and cholestasis markers. An upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy was performed, which revealed bleeding from the duodenal papilla. A CT angiogram showed a 2-cm pseudoaneurysmal lesion adjacent to the infundibulum of the gallbladder, with a large gallstone lying in that region (Fig. 1) as well as signs of acute cholecystitis. The patient had a vascular anatomical variant: common hepatic artery with origin in the superior mesenteric artery, dividing into 3 branches before the hepatic hilum. An arteriogram was then performed which revealed the pseudoaneurysmal lesion, without managing to identify the artery supplying the pseudoaneurysm, making embolisation impossible. Finally, the patient underwent laparoscopic surgery, which revealed acute cholecystitis with active gallbladder bleeding, requiring conversion to open cholecystectomy. He had a large 3×2cm gallstone lying against the wall of the gallbladder within the infundibulum, eroding the aforementioned pseudoaneurysm.

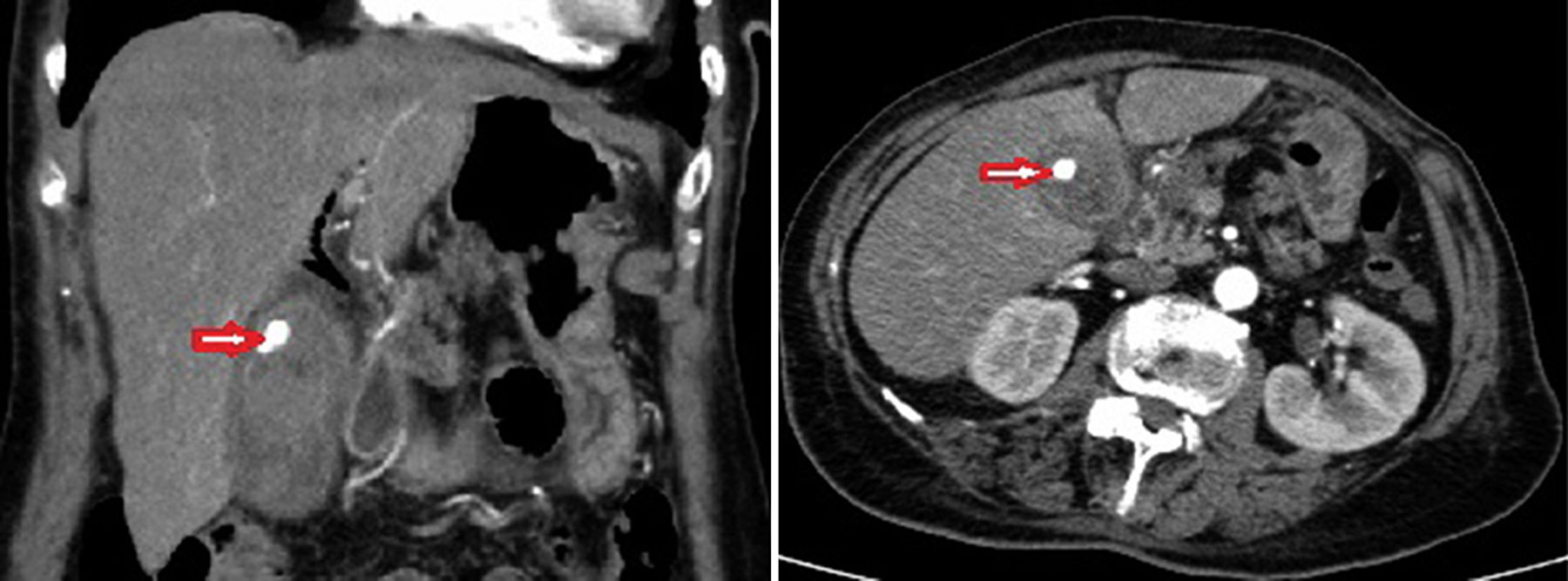

The second case is a 74-year-old female patient with right upper quadrant pain, fever and melaena, who developed anaemia during her hospital stay. She had elevated cytolysis and cholestasis markers. An abdominal ultrasound revealed acute cholecystitis with echogenic material within the gallbladder lumen and dilatation of the intrahepatic bile duct. The upper GI endoscopy showed blood clots in the 2nd part of the duodenum extruding from the papilla. An endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was performed to remove blood clots from the main bile duct. A CT angiogram revealed acute cholecystitis and a pseudoaneurysmal lesion of the cystic artery, with no signs of active bleeding, although there was hyperdense material within the gallbladder, suggesting intraluminal bleeding (Fig. 2). Finally, a laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed, which confirmed the presence of acute cholecystitis with a large blood clot and two 2-cm gallstones in the gallbladder.

Both patients had a favourable outcome with no further gastrointestinal bleeding.

Vascular disorders are an uncommon cause of haemobilia. Aneurysms or pseudoaneurysms occur mainly in the hepatic artery or one of its branches.3 Cases of haemobilia caused by vascular disorders of the cystic artery are very rare and generally occur following iatrogenic trauma, such as a laparoscopic cholecystectomy.4 Non-traumatic pseudoaneurysms of the cystic artery are rare and are generally due to inflammatory processes of the gallbladder, which, due to their proximity, cause vascular lesions which may produce a fistula between the artery and the gallbladder. The inflammatory process damages the vascular adventitia and causes thrombosis of the vasa vasorum, weakening the vessel wall. Another mechanism involved is erosion caused directly by large gallstones, which may lie against the cystic artery.5,6

The diagnostic methods to be used in these cases will depend on the patient's haemodynamic status. Provided that the patient remains stable, the first exam to be performed should be an upper GI endoscopy, which will allow doctors to rule out other sources of gastrointestinal bleeding and check for signs of bleeding from the papilla. Nevertheless, this does not allow treatment at the source of the bleeding and may give negative results if bleeding is intermittent.6

A CT angiogram is very useful because, in addition to revealing lesions that are the source of bleeding, it also identifies contrast extravasation if extensive enough.7

The most important examination method in cases of haemobilia with proven (generally by CR angiogram) or suspected active bleeding is angiography, especially since it allows for selective embolisation of the bleeding vessel.3 More and more authors consider embolisation to be the gold standard for the initial treatment of haemobilia with proven active bleeding, especially in high-risk surgical patients.6,7 Nevertheless, the intermittent nature of bleeding or the presence of atherosclerotic plaque, tortuous vessels or anatomical variants (as in our first case study) may make embolisation attempts impossible.2 Unlike cases of haemobilia involving branches of the hepatic artery, where the embolisation success rate is reasonably high (reaching up to 100%),8 the success rate in pseudoaneurysms of the cystic artery is lower (40%).7 The gallbladder must generally be removed following embolisation of the cystic artery due to the risk of gallbladder ischaemia, although some cases not requiring cholecystectomy but with good outcomes have been reported.7

Despite the possibility of angiographic treatment, most authors consider laparoscopic cholecystectomy with ligation of the cystic artery to be the treatment of choice. The patient's situation or technical complications may require use of or conversion to an open surgical procedure.

To conclude, the treatment of choice is cholecystectomy with ligation of the cystic artery, preferably using a laparoscopic approach, although angiographic treatment is an ideal alternative for haemodynamically stable, high-risk surgical patients.

Please cite this article as: Medina Velázquez R, Casimiro Pérez JA, Acosta Mérida MA, Marchena Gómez J. Pseudoaneurisma no traumático de la arteria cística como causa de hemobilia. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:257–259.