Primary colorectal lymphoma comprises 10–20% of lymphomas, and only 0.2–0.6% of malignant neoplasms of the large intestine. Its clinical presentation is nonspecific, and its diagnosis late. Most are non-Hodgkin lymphomas, with the most common histological subtype being diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.1–3

We present the case of a 28-year-old male, who sought medical advice due to a sensation of rigidity in the right iliac fossa, which in less than 30 days became a large mass, visible to the naked eye in supine position. Associated with this, he presented marked anorexia and a weight loss of 9kg over the past 3 months, with a sensation of fullness after eating and intermittent abdominal pain.

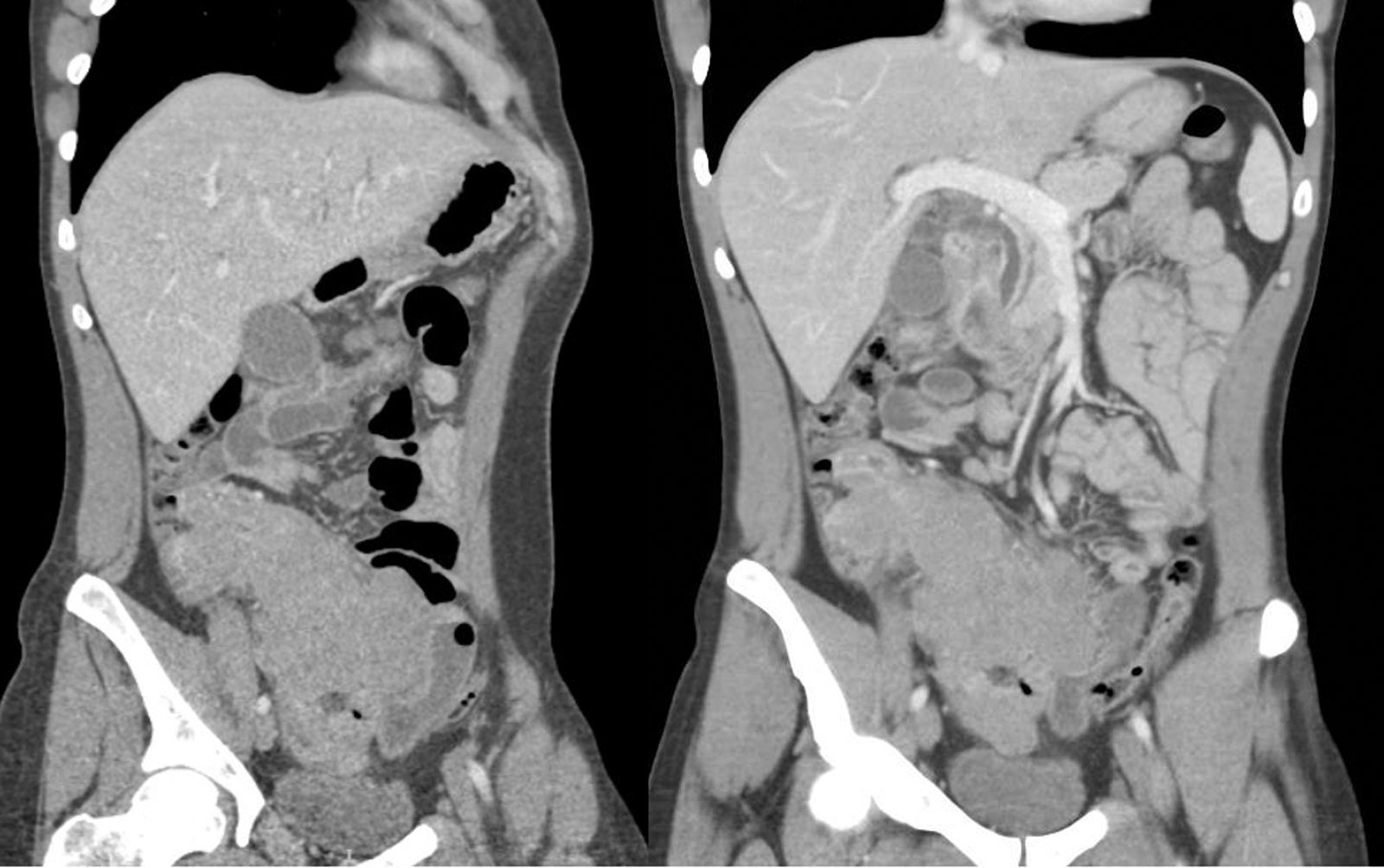

An abdominal CT scan with contrast was performed, showing marked ascending colon wall thickening, ileocolic lymphadenopathies, duodenal wall thickening, minimal dilation of the bile ducts and hypodense lesions in the pancreatic body-neck (Fig. 1).

As regards his blood tests, moderate hypertransaminasaemia and cholestasis were notable, with normal tumour markers, including β2-microglobulin.

The colonoscopy showed a normal mucosa and colon calibre up to the ascending colon where good luminal distension was not obtained, while the ileoscopy revealed extensive necrotic ulcerations suggestive of intestinal lymphoma, which were biopsied. In the oral endoscopy, similar ulcerations were seen in the proximal duodenum.

The histology was reported as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the germinal centre immunophenotype.

The initial staging PET-CT showed extensive intestinal lymphomatous involvement in the hypogastrium and right iliac fossa, with a central metabolic zone compatible with necrosis, confirming a posterior intestinal perforation of the ascending colon by CT, which required an urgent right hemicolectomy, with a partial small intestine resection and latero-lateral ileocolic anastomosis, in light of the macroscopic finding of a large tumour mass occupying the entire ascending colon, caecum and terminal ileum, without the involvement of other neighbouring organs.

The histology of the surgical specimen revealed a high-grade, intermediate-large cell lymphoproliferative process, with starry-sky areas and necrotic foci, associated with Epstein–Barr virus (intensely positive EBERs), with a high proliferative index (Ki-67, almost 100%) and a Bcl-2 negative and CD20 positive germinal centre phenotype. Although the translocation t(8;14) was negative, Burkitt lymphoma associated with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) was reported based on the cellularity, association with Epstein–Barr virus and the extremely high proliferative index of the lymphoma (Ki-67, almost 100%), which is typical of this neoplasm compared to other types of lymphoproliferative diseases. The surgical specimen contained large mesenteric lymph nodes, not infiltrated by the lymphoma.

It was classified as stage IVB Burkitt lymphoma and chemotherapy was initiated in a clinical trial regimen. After two cycles, he has shown an excellent intermediate metabolic response to chemotherapy by PET-CT, and is awaiting his last cycle of chemotherapy.

Primary colorectal lymphoma is a very uncommon malignant neoplasm. Burkitt lymphoma accounts for only 15% of all gastrointestinal lymphomas.4

The most common symptoms are abdominal pain, anorexia and weight loss.1,3 The lack of specificity often leads to a delay in its diagnosis.

Colonoscopy is a useful diagnostic tool, despite frequent errors in the histological diagnosis of biopsies, due to the collection of samples of non-specific adjacent tissue. In the Ding et al. series, lesions were identified macroscopically in 95.7% of cases (44/46), while biopsies were diagnostic in only 21.7% (10/46).5 In all other cases, the biopsies showed no alterations or diagnostic errors, as occurred in our case.

Endoscopic findings range from ulcerations to polypoid lesions.2,3

Burkitt lymphoma is characterized by its association with chromosomal translocation (8:14, 8:22 and 2:8), and overexpression of the c-Myc oncogene. It is the fastest-growing lymphoma. Its incidence is higher in children, and is uncommon in adulthood.

There are three clinical variants: endemic (associated with malaria and EBV in most cases), immunosuppression-related (associated with HIV and EBV in 40%) and sporadic, associated with EBV in 20%, like ours. The influence of EBV on the pathogenesis of Burkitt lymphoma is unknown.6

Rapid tumour growth and late diagnosis (non-specific symptoms, variable macroscopic appearance and low cost-effectiveness of endoscopic biopsy) frequently imply the need for an urgent laparotomy, prior to the histological confirmation and initiation of treatment, due to complications (bowel obstruction, perforation or haemorrhage).

The treatment of choice is chemotherapy, administered aggressively in adults due to its worse prognosis and treatment response.7 The cure rate is 90% in developed countries. Early diagnosis is essential to ensure optimal medical treatment and avoid surgical complications.

FundingWe have not received funding for the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of interestNone of the authors has any conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Sendra-Fernández C, Pizarro-Moreno Á, Silva-Ruiz P, Mejías-Manzano MÁ. Linfoma de Burkitt con extensa afectación ileocolónica. Presentación como masa abdominal de crecimiento rápido. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:288–290.