To assess the comorbidity, concomitant medications, healthcare resource use and healthcare costs of chronic hepatitis C virus patients in the Spanish population.

Patients and methodsRetrospective, observational, non-interventional study. Patients included were ≥18 years of age who accessed medical care between 2010 and 2013. Patients were divided into 2 groups based on the presence or absence of liver cirrhosis. The follow-up period was 12 months. Main assessment criteria included general comorbidity level (determined by the resource utilisation band score) and prevalence of specific comorbidities, concomitant medications, healthcare resource use and healthcare costs. Statistical analysis was performed using regression models and ANCOVA, p<.05.

ResultsOne thousand fifty-five patients were enrolled, the mean age was 57.9 years and 55.5% were male. A percentage of 43.5 of patients had a moderate level of comorbidity according to the resource utilisation band score. The mean time from diagnosis was 18.1 years and 7.5% of the patients died during the follow-up period. The most common comorbidities were dyslipidaemia (40.3%), hypertension (40.1%) and generalised pain (38.1%). Cirrhosis was associated with cardiovascular events (OR 3.8), organ failures (OR 2.2), alcoholism (OR 2.1), diabetes (OR 1.2) and age (OR 1.2); p<.05. The most commonly used medications were anti-infectives (67.8%) and nervous system medications (66.8%). The mean total cost per patient was €3198 (71.5% healthcare costs, 28.5% indirect/non-healthcare costs). In the corrected model, the total costs per patient-year were €2211 for those without cirrhosis and €7641 for patients with cirrhosis; p<.001.

ConclusionsChronic hepatitis C virus patients are associated with a high level of comorbidity and the use of concomitant medications, especially in patients with liver cirrhosis. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection represents a substantial economic burden on the Spanish National Health System.

Evaluar la comorbilidad, los medicamentos concomitantes, el uso de los recursos y los costes sanitarios asociados a los pacientes portadores del virus de la hepatitis C crónica en población española.

Pacientes y métodosEstudio retrospectivo, observacional, no intervencionista. Se incluyeron pacientes≥18 años, que demandaron atención durante los años 2010-2013. Se dividieron en 2 grupos en función de la presencia/ausencia de cirrosis hepática. El período de seguimiento fue de 12 meses. Las principales mediciones fueron: comorbilidad general (banda de utilización de recursos) y específica, medicamentos concomitantes, uso de recursos y costes sanitarios. El análisis estadístico fue realizado utilizando modelos de regresión y ANCOVA, p<0,05.

ResultadosSe seleccionaron 1.055 pacientes con una edad media de 57,9 años, y el 55,5% eran varones. El 43,5% de los pacientes presentaron un grado de comorbilidad moderado (banda de utilización de recursos). El tiempo medio desde el diagnóstico fue de 18,1 años y el 7,5% de los pacientes fallecieron durante el período de seguimiento. Las comorbilidades más frecuentes fueron: dislipidemia (40,3%), hipertensión (40,1%) y dolor generalizado (38,1%). La cirrosis se asoció con los eventos cardiovasculares (OR 3,8), los fallos orgánicos (OR 2,2), el alcoholismo (OR 2,1), la diabetes (OR 1,2) y la edad (OR 1,2); p<0,05. Los medicamentos más utilizados fueron antiinfecciosos (67,8%) y fármacos para el sistema nervioso (66,8%). El coste total medio por paciente fue de 3.198€ (71,5% costes sanitarios, 28,5% costes indirectos/no sanitarios). En el modelo corregido, el coste total por paciente-año fue de 2.211€ sin cirrosis y de 7.641€ con cirrosis; p<0,001.

ConclusionesLos pacientes con virus de la hepatitis C crónica se asocian a una elevada comorbilidad y uso de medicación concomitante, especialmente en los sujetos con cirrosis hepática. La infección por virus de la hepatitis C crónica supone una importante carga económica para el Sistema Nacional de Salud.

Hepatitis C is a liver disease caused by the hepatitis C virus.1 The virus is transmitted parenterally, with its main routes of infection being blood transfusion products and the shared use of needles for intravenous drug use.1,2 It is a global health problem that affects more than 170 million people worldwide. The prevalence in Europe varies according to country and ranges between 2% and 3% of the overall population.2–4

Following the natural course of the disease, it is known that 60–90% of infected patients will develop chronic hepatitis C (CHC) and 20% of these will develop cirrhosis.1,3 The decompensation of cirrhosis can cause liver failure or hepatocellular carcinoma (3–5% at 5 years). Therefore, early detection and treatment are very important for its prevention.1,2,5–7 It has been estimated that CHC is responsible for approximately one million deaths per year worldwide.3

The objective of current therapy for CHC is to achieve a sustained viral response, defined as the absence of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-RNA in serum 12 weeks after stopping treatment.8 The standard procedure for patients with CHC is rapidly changing; until recently, treatment was based on interferon and ribavirin, with a 50% cure rate, although it sometimes caused frequent adverse reactions. In recent years, new and innovative direct-acting antiviral medications have been developed, which are much more effective and safe and better tolerated than former treatments, allowing oral administration. Treatment with oral direct-acting antivirals can cure most patients infected with HCV. Therefore, the new therapeutic arsenal available against this disease forces us to identify those patients most likely to benefit from the best therapeutic strategy available.8–10

The social and economic burden of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is considerable and has resulted in the World Health Organisation recommending local studies to define the extent of the problem and to prioritise preventive measures.10–15 According to one naturalistic study conducted in Italy, liver disease represents a mean monthly cost of €645 per patient, with hospitalisation contributing to 50% of costs.11 In Spain, despite having clinical guidelines that support adequate management of these patients,16 there is little information on the true economic burden of HCV infection, covering both direct costs for the use of healthcare services and indirect costs to society (loss of productivity). Although a reduction in the number of new cases of hepatitis C is foreseen over the coming years,2 the total number of cases of chronic liver disease seen in Spain is likely to increase. This is partly due to screening strategies used to identify asymptomatic cases of chronic hepatitis and partly due to decompensation of undiagnosed cases of latent cirrhosis (hepatic morbidity), which increases the cost of the disease.1,2,14 The aim of this study was to evaluate comorbidities, concomitant medications, use of resources and healthcare costs associated with CHC patients in Spain.

Patients and methodsStudy design and populationAn observational retrospective study was conducted based on medical records (computerised databases with anonymous data) of patients seen at 8 Primary Care centres (PC; La Roca del Vallés and Girona; Barcelona). The population assigned to these centres was primarily urban, lower-middle class and predominantly industrial.

Inclusion/exclusion criteriaPatients with CHC diagnosis according to the International Classification of Primary Care (D72)17 and/or the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (070.4, 070.5), who required medical care between 01/01/2010 and 31/12/2013 (index date) were identified. They had to meet the following criteria: (a) age ≥18 years; (b) be diagnosed with CHC at least 12 months prior to the start of the study (active patients in the database); (c) be in the chronic prescriptions programme (with records of the daily dose, interval and duration of each treatment, ≥2 prescriptions during the follow-up period); and (d) have proof that regular follow-up of these patients during the study period will be possible (≥2 healthcare records in the computer system). Patients transferred to other centres, or patients who had moved and/or who were outside the area were excluded from the study.

Study and follow-up groupsPatients were classified into 2 groups based on the presence or absence of prior cirrhosis (D97). Patients were followed for 12 months from the date of the first outpatient contact (medical visit with primary care doctor or specialist).

Diagnosis of chronic hepatitis C and cirrhosisThe CHC diagnosis was obtained from the International Classification of Primary Care17 (D72) and hospital discharge and emergency codes were in accordance with the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (070.4, 070.5). Specific anti-HCV antibodies were detected in all patients included in the study and an HCV-RNA test was performed to confirm chronic infection. The diagnosis of cirrhosis was obtained from the diagnostic code.17 Clinical diagnosis was determined in all cases by an ultrasound of the liver and in some cases by liver biopsy or FibroScan.

Socio-demographic and comorbidity variablesThe variables were: age (continuous and by range: 18–44, 45–64, 65–74 and over 74); gender; body mass index (kg/m2) and time since diagnosis of the disease (hepatitis C), as well as the following personal history17: hypertension (K86, K87); diabetes (T90); lipid disorder (T93); obesity (T82); active smoker (P17); alcohol abuse (P15, P16); all types of organ failure (heart, liver); coronary heart disease (codes K74, K76, K75); cerebrovascular accident (K90, K91, K93); chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (R95, chronic airflow obstruction); bronchial asthma (R96); dementia or cognitive impairment (P70, P20); neurological diseases: Parkinson's disease (N87), epilepsy (N88), multiple sclerosis (N86) and other neurological diseases (N99); depressive disorder (P76); generalised anxiety disorder (P74); psychosis (P72, schizophrenia); malignant neoplasms (A79, B72-75, D74-78, F75, H75, K72, L71, L97, N74-76, R84-86, T71-73, U75-79, W72-73, X75-81, Y77-79); HIV (B90); anaemia (all types); chronic renal failure (U99); generalised pain (A01); tuberculosis (A70). As a summary variable of the general comorbidity for each patient, the following was used: (a) the Charlson comorbidity index18 as an indicator of severity; and (b) the individual case-mix index, obtained from the adjusted clinical groups, which is a patient classification system for iso-consumption of resources.19 The adjusted clinical groups application provides resource utilisation bands (RUB), where each patient, based on their general morbidity, is grouped into one of 5 mutually-exclusive categories: 1: healthy users or very low morbidity; 2: low morbidity; 3: moderate morbidity; 4: high morbidity; and 5: very high morbidity).

Concomitant medicationsDue to the retrospective and non-interventional nature of the study design, the assignment of a patient to a particular therapeutic strategy was determined based on current clinical practice (at the treating clinician's discretion). Information was obtained for the following therapeutic groups according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System20: Group A (Alimentary tract and metabolism), Group B (Blood and blood forming organs), Group C (Cardiovascular system), Group D (Dermatologicals), G Group (Genito urinary system and sex hormones), Group H (Systemic hormonal preparations, excluding sex hormones and insulins), Group J (Antiinfectives for systemic use), Group L (Antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents), Group M (Musculo-skeletal system), Group N (Nervous system), Group R (Respiratory system) and Group S (Sensory organs). Information was then divided in more detail into major subgroups of the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System, such as antibiotics, antiepileptics, anti-asthmatics, lipid modifying agents, etc. The information was obtained from the dispensing of pharmaceuticals for prescriptions filled by the pharmacy, according to the pharmaceutical prescription monitoring application of CatSalut.

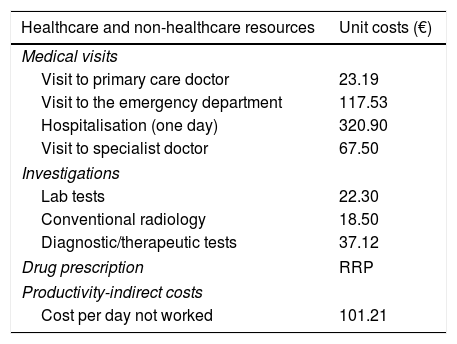

Use of resources and costsHealthcare costs related to healthcare activities (medical visits, days of hospitalisation, emergency, diagnostic or therapeutic requests and medication) provided by professionals, and non-healthcare costs (indirect) related to loss of productivity (days of disability/temporary leave; source: electronic medical record) were considered. Cost was expressed as mean cost per patient (annual cost/unit). Table 1 shows the various study concepts and their economic valuations (for 2014). The different fees were obtained from the analytical accounting of the centres, except medication and days off work. Prescriptions (acute, chronic and/or on-demand) were quantified by retail price per pack at the time of prescription. The cost of test strips to determine capillary glucose values was included. The days of occupational disability or loss of productivity were quantified according to the average interprofessional wage (source: INE).21 Patients with temporary or permanent disability were quantified in terms of work days missed. This study did not contemplate non-healthcare direct costs, i.e. those considered “out-of-pocket” costs paid by the patient/family, as they are not recorded in the database. The retroviral medication administered to patients was excluded from the cost analysis.

Details of unit costs and loss of productivity (for 2014).

| Healthcare and non-healthcare resources | Unit costs (€) |

|---|---|

| Medical visits | |

| Visit to primary care doctor | 23.19 |

| Visit to the emergency department | 117.53 |

| Hospitalisation (one day) | 320.90 |

| Visit to specialist doctor | 67.50 |

| Investigations | |

| Lab tests | 22.30 |

| Conventional radiology | 18.50 |

| Diagnostic/therapeutic tests | 37.12 |

| Drug prescription | RRP |

| Productivity-indirect costs | |

| Cost per day not worked | 101.21 |

RRP: recommended retail price including VAT.

Source of healthcare resources: analytical accounting done by the authors and the Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE – Spanish Statistics Institute).

Records (anonymous and pseudonymous) were kept confidential according to the Organic Data Protection Law (Organic Law 15/1999 of December 13). The study was classified by the Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios (Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices) (EPA-OD) and was subsequently approved by the Independent Ethics Committee of the Unió Catalana d’Hospitals de Barcelona.

Statistical analysisA univariate descriptive statistical analysis was conducted for the variables of interest. For qualitative data, the absolute and relative frequency were calculated. Ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were based on the total number of subjects with no missing values. For quantitative data, the mean and standard deviation were used. Goodness of fit to the normal distribution was evaluated using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The analysis of variance, chi-square test and Pearson correlation coefficient were used for the bivariate analysis. A logistic regression analysis was performed to obtain variables associated with the profiles of patients with cirrhosis (dependent variable), using the Enter procedure (statistic: Wald). Costs were compared according to recommendations outlined by Thompson and Barber22 by analysis of covariance (generalised linear model: ANCOVA), with gender, age, RUBs, Charlson comorbidity index and time since diagnosis as covariables. SPSSWIN Version 18 software was used, with statistical significance set at p values <0.05.

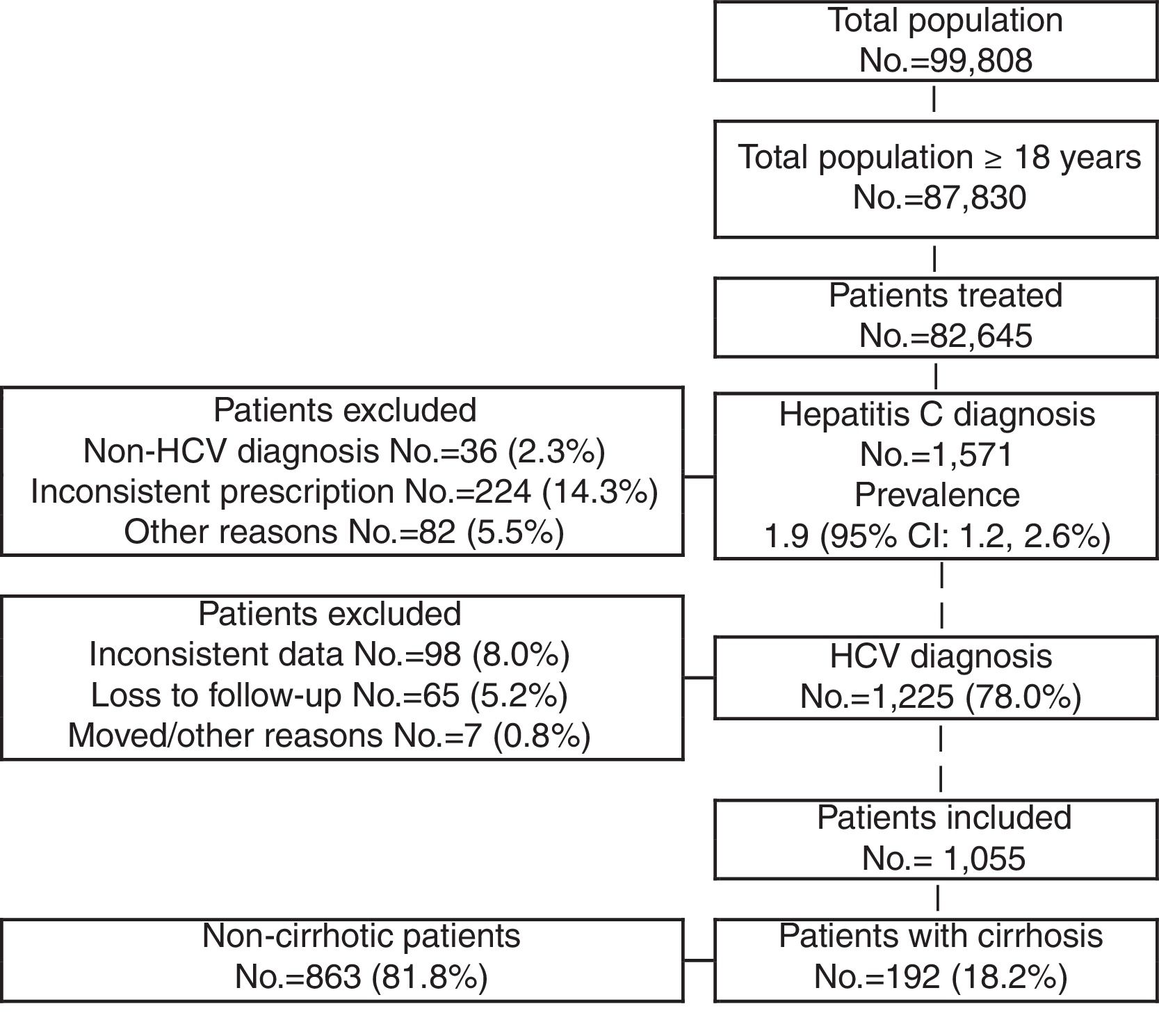

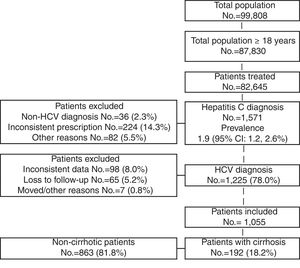

ResultsOf an initial population of 87,830 subjects ≥18 years, 82,645 patients received care during the period of 2010–2013. Of these, 1571 were diagnosed as HCV carriers (prevalence 1.9%; 95% CI 1.2–2.6). Finally, 1055 HCV carriers who met the inclusion/exclusion criteria and who could be followed during the study period were analysed (Fig. 1).

Study flowchart. A restrospective observational design was created, based on the review of medical records (computerised databases, with anonymous data) of patients followed at outpatient and inpatient clinics who required healthcare between 2010 and 2013.

HCV: chronic hepatitis C virus.

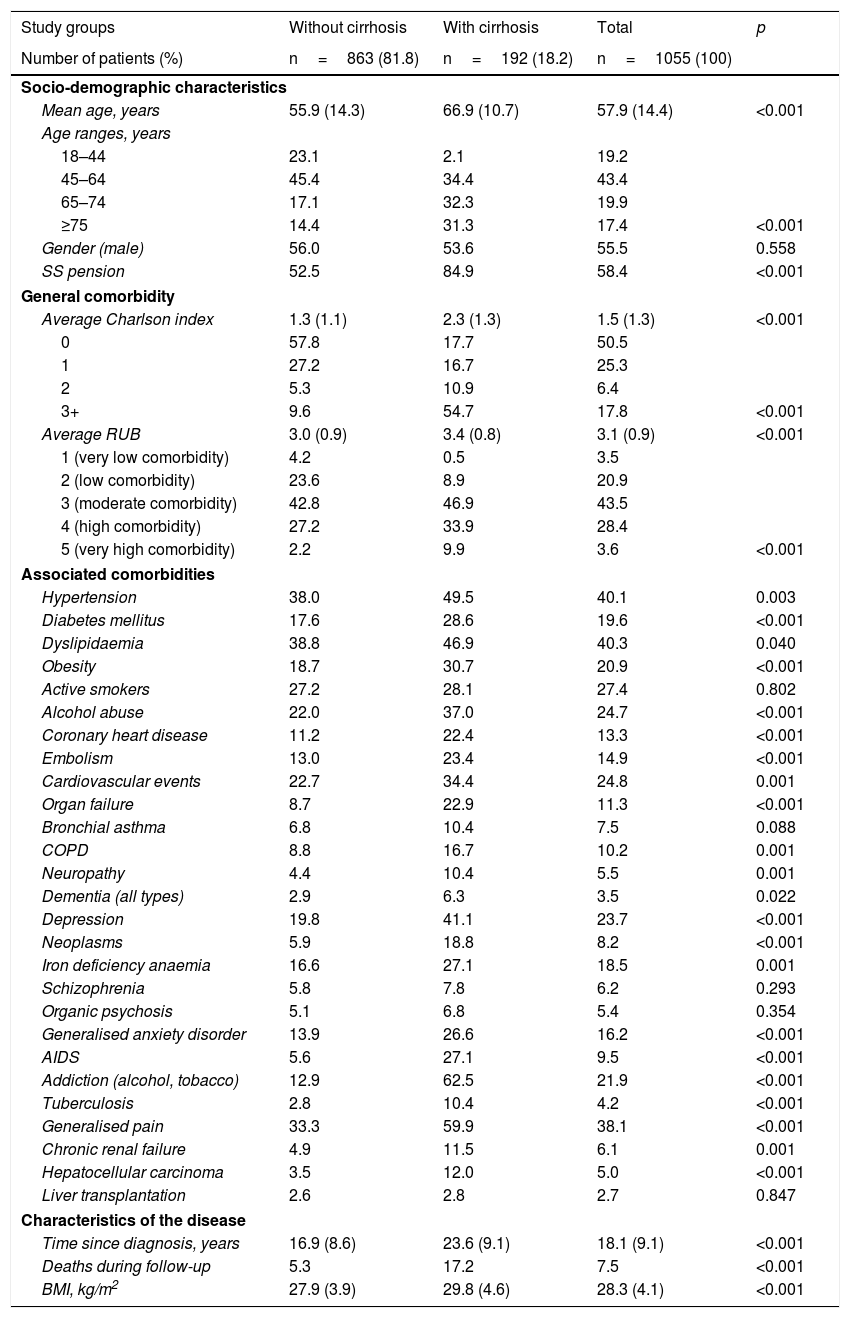

Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics of the group of patients studied based on the presence/absence of cirrhosis. The mean age was 57.9 years (43.4% of patients were 45–64 years), 55.5% were men and the mean RUB score was 3.1 points per patient (moderate comorbidity, 43.5%). Dyslipidaemia (40.3%), hypertension (40.1%) and generalised pain (38.1%) were the most common comorbidities. Cardiovascular and mental illnesses were also prevalent personal histories. Mean time since diagnosis was 18.1 years and 7.5% of patients died during the follow-up period. Of the 1055 patients included in the study, 192 (18.2%) had cirrhosis. Most of the variables studied (demographic characteristics, general/specific and disease-related comorbidities) were higher with the presence of cirrhosis. In the logistic regression model, cirrhosis was associated primarily with cardiovascular events (OR 3.8; 95% CI 2.5–6.8), organ failure (OR 2.2; 95% CI 1.3–3.2), alcohol abuse (OR 2.1; 95% CI 1.3–3.3), diabetes (OR 1.2; 95% CI 1.1–1.5) and age (OR 1.2; 95% CI 1.1–1.3).

Baseline characteristics of the patients studied.

| Study groups | Without cirrhosis | With cirrhosis | Total | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (%) | n=863 (81.8) | n=192 (18.2) | n=1055 (100) | |

| Socio-demographic characteristics | ||||

| Mean age, years | 55.9 (14.3) | 66.9 (10.7) | 57.9 (14.4) | <0.001 |

| Age ranges, years | ||||

| 18–44 | 23.1 | 2.1 | 19.2 | |

| 45–64 | 45.4 | 34.4 | 43.4 | |

| 65–74 | 17.1 | 32.3 | 19.9 | |

| ≥75 | 14.4 | 31.3 | 17.4 | <0.001 |

| Gender (male) | 56.0 | 53.6 | 55.5 | 0.558 |

| SS pension | 52.5 | 84.9 | 58.4 | <0.001 |

| General comorbidity | ||||

| Average Charlson index | 1.3 (1.1) | 2.3 (1.3) | 1.5 (1.3) | <0.001 |

| 0 | 57.8 | 17.7 | 50.5 | |

| 1 | 27.2 | 16.7 | 25.3 | |

| 2 | 5.3 | 10.9 | 6.4 | |

| 3+ | 9.6 | 54.7 | 17.8 | <0.001 |

| Average RUB | 3.0 (0.9) | 3.4 (0.8) | 3.1 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| 1 (very low comorbidity) | 4.2 | 0.5 | 3.5 | |

| 2 (low comorbidity) | 23.6 | 8.9 | 20.9 | |

| 3 (moderate comorbidity) | 42.8 | 46.9 | 43.5 | |

| 4 (high comorbidity) | 27.2 | 33.9 | 28.4 | |

| 5 (very high comorbidity) | 2.2 | 9.9 | 3.6 | <0.001 |

| Associated comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 38.0 | 49.5 | 40.1 | 0.003 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 17.6 | 28.6 | 19.6 | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 38.8 | 46.9 | 40.3 | 0.040 |

| Obesity | 18.7 | 30.7 | 20.9 | <0.001 |

| Active smokers | 27.2 | 28.1 | 27.4 | 0.802 |

| Alcohol abuse | 22.0 | 37.0 | 24.7 | <0.001 |

| Coronary heart disease | 11.2 | 22.4 | 13.3 | <0.001 |

| Embolism | 13.0 | 23.4 | 14.9 | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular events | 22.7 | 34.4 | 24.8 | 0.001 |

| Organ failure | 8.7 | 22.9 | 11.3 | <0.001 |

| Bronchial asthma | 6.8 | 10.4 | 7.5 | 0.088 |

| COPD | 8.8 | 16.7 | 10.2 | 0.001 |

| Neuropathy | 4.4 | 10.4 | 5.5 | 0.001 |

| Dementia (all types) | 2.9 | 6.3 | 3.5 | 0.022 |

| Depression | 19.8 | 41.1 | 23.7 | <0.001 |

| Neoplasms | 5.9 | 18.8 | 8.2 | <0.001 |

| Iron deficiency anaemia | 16.6 | 27.1 | 18.5 | 0.001 |

| Schizophrenia | 5.8 | 7.8 | 6.2 | 0.293 |

| Organic psychosis | 5.1 | 6.8 | 5.4 | 0.354 |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | 13.9 | 26.6 | 16.2 | <0.001 |

| AIDS | 5.6 | 27.1 | 9.5 | <0.001 |

| Addiction (alcohol, tobacco) | 12.9 | 62.5 | 21.9 | <0.001 |

| Tuberculosis | 2.8 | 10.4 | 4.2 | <0.001 |

| Generalised pain | 33.3 | 59.9 | 38.1 | <0.001 |

| Chronic renal failure | 4.9 | 11.5 | 6.1 | 0.001 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 3.5 | 12.0 | 5.0 | <0.001 |

| Liver transplantation | 2.6 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 0.847 |

| Characteristics of the disease | ||||

| Time since diagnosis, years | 16.9 (8.6) | 23.6 (9.1) | 18.1 (9.1) | <0.001 |

| Deaths during follow-up | 5.3 | 17.2 | 7.5 | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.9 (3.9) | 29.8 (4.6) | 28.3 (4.1) | <0.001 |

RUB: resource utilisation bands; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BMI: body mass index; SS: social security.

Values expressed as percentage or mean (standard deviation).

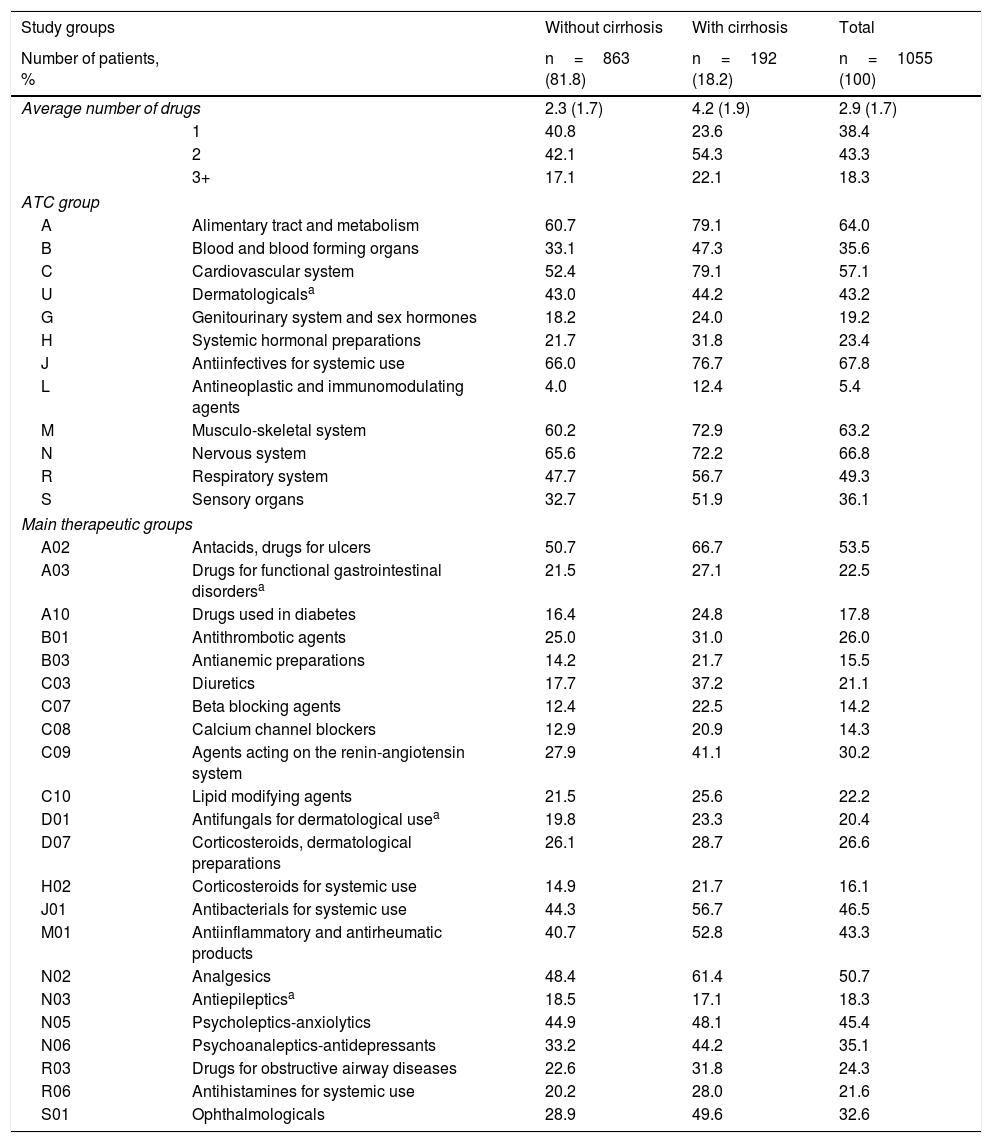

Concomitant medications administered to patients during the follow-up period are shown in Table 3. The mean number of drugs administered was 2.9 (SD 1.7) per patient-year. In general, the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System categories most commonly used were: Antiinfectives for systemic use (67.8%), Nervous system (66.8%), Alimentary tract and metabolism (64.0%), Musculo-skeletal system (63.2%) and Cardiovascular system (57.1%). The main treatment groups were: A02-Antacids (53.5%), N02-Analgesics (50.7%), J01-Antibacterials (46.5%), N05-Anxiolytics (45.4%) and M01-Antiinflammatory products (43.3%). In most of the groups studied, patients with cirrhosis tended to use a higher number of medications than those patients without cirrhosis, with a general mean of 4.2 versus 2.3 medications per patient-year, respectively (p<0.001).

Concomitant medication administered during the follow-up period.

| Study groups | Without cirrhosis | With cirrhosis | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients, % | n=863 (81.8) | n=192 (18.2) | n=1055 (100) | |

| Average number of drugs | 2.3 (1.7) | 4.2 (1.9) | 2.9 (1.7) | |

| 1 | 40.8 | 23.6 | 38.4 | |

| 2 | 42.1 | 54.3 | 43.3 | |

| 3+ | 17.1 | 22.1 | 18.3 | |

| ATC group | ||||

| A | Alimentary tract and metabolism | 60.7 | 79.1 | 64.0 |

| B | Blood and blood forming organs | 33.1 | 47.3 | 35.6 |

| C | Cardiovascular system | 52.4 | 79.1 | 57.1 |

| U | Dermatologicalsa | 43.0 | 44.2 | 43.2 |

| G | Genitourinary system and sex hormones | 18.2 | 24.0 | 19.2 |

| H | Systemic hormonal preparations | 21.7 | 31.8 | 23.4 |

| J | Antiinfectives for systemic use | 66.0 | 76.7 | 67.8 |

| L | Antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents | 4.0 | 12.4 | 5.4 |

| M | Musculo-skeletal system | 60.2 | 72.9 | 63.2 |

| N | Nervous system | 65.6 | 72.2 | 66.8 |

| R | Respiratory system | 47.7 | 56.7 | 49.3 |

| S | Sensory organs | 32.7 | 51.9 | 36.1 |

| Main therapeutic groups | ||||

| A02 | Antacids, drugs for ulcers | 50.7 | 66.7 | 53.5 |

| A03 | Drugs for functional gastrointestinal disordersa | 21.5 | 27.1 | 22.5 |

| A10 | Drugs used in diabetes | 16.4 | 24.8 | 17.8 |

| B01 | Antithrombotic agents | 25.0 | 31.0 | 26.0 |

| B03 | Antianemic preparations | 14.2 | 21.7 | 15.5 |

| C03 | Diuretics | 17.7 | 37.2 | 21.1 |

| C07 | Beta blocking agents | 12.4 | 22.5 | 14.2 |

| C08 | Calcium channel blockers | 12.9 | 20.9 | 14.3 |

| C09 | Agents acting on the renin-angiotensin system | 27.9 | 41.1 | 30.2 |

| C10 | Lipid modifying agents | 21.5 | 25.6 | 22.2 |

| D01 | Antifungals for dermatological usea | 19.8 | 23.3 | 20.4 |

| D07 | Corticosteroids, dermatological preparations | 26.1 | 28.7 | 26.6 |

| H02 | Corticosteroids for systemic use | 14.9 | 21.7 | 16.1 |

| J01 | Antibacterials for systemic use | 44.3 | 56.7 | 46.5 |

| M01 | Antiinflammatory and antirheumatic products | 40.7 | 52.8 | 43.3 |

| N02 | Analgesics | 48.4 | 61.4 | 50.7 |

| N03 | Antiepilepticsa | 18.5 | 17.1 | 18.3 |

| N05 | Psycholeptics-anxiolytics | 44.9 | 48.1 | 45.4 |

| N06 | Psychoanaleptics-antidepressants | 33.2 | 44.2 | 35.1 |

| R03 | Drugs for obstructive airway diseases | 22.6 | 31.8 | 24.3 |

| R06 | Antihistamines for systemic use | 20.2 | 28.0 | 21.6 |

| S01 | Ophthalmologicals | 28.9 | 49.6 | 32.6 |

ATC: Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System.

Values expressed as percentage or mean (standard deviation).

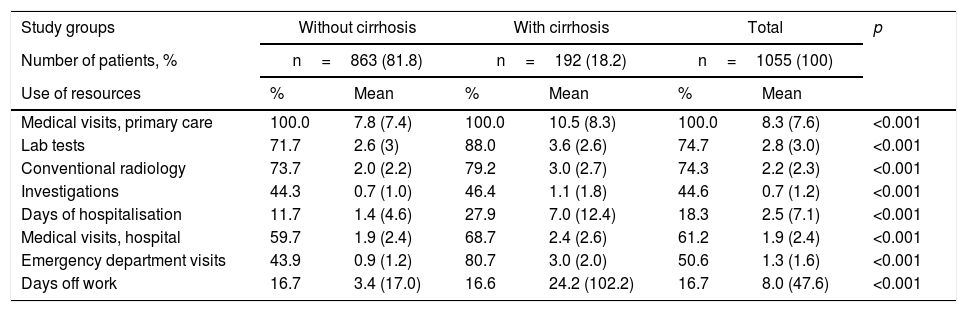

Compared with patient without cirrhosis, patients with cirrhosis had a higher mean number of Primary Care visits (10.5 versus 7.8; p<0.001), days of hospitalisation (7.0 versus 1.4; p<0.001), Specialised Care visits (2.4 versus 1.9; p<0.001) and hospital emergency visits (3.0 versus 0.9; p<0.001) (Table 4). There were also differences in the number of days off work (34.2 versus 3.4; p<0.001). A total of 21 patients were receiving temporary-permanent disability.

Use of resources by study groups.

| Study groups | Without cirrhosis | With cirrhosis | Total | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients, % | n=863 (81.8) | n=192 (18.2) | n=1055 (100) | ||||

| Use of resources | % | Mean | % | Mean | % | Mean | |

| Medical visits, primary care | 100.0 | 7.8 (7.4) | 100.0 | 10.5 (8.3) | 100.0 | 8.3 (7.6) | <0.001 |

| Lab tests | 71.7 | 2.6 (3) | 88.0 | 3.6 (2.6) | 74.7 | 2.8 (3.0) | <0.001 |

| Conventional radiology | 73.7 | 2.0 (2.2) | 79.2 | 3.0 (2.7) | 74.3 | 2.2 (2.3) | <0.001 |

| Investigations | 44.3 | 0.7 (1.0) | 46.4 | 1.1 (1.8) | 44.6 | 0.7 (1.2) | <0.001 |

| Days of hospitalisation | 11.7 | 1.4 (4.6) | 27.9 | 7.0 (12.4) | 18.3 | 2.5 (7.1) | <0.001 |

| Medical visits, hospital | 59.7 | 1.9 (2.4) | 68.7 | 2.4 (2.6) | 61.2 | 1.9 (2.4) | <0.001 |

| Emergency department visits | 43.9 | 0.9 (1.2) | 80.7 | 3.0 (2.0) | 50.6 | 1.3 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| Days off work | 16.7 | 3.4 (17.0) | 16.6 | 24.2 (102.2) | 16.7 | 8.0 (47.6) | <0.001 |

Values expressed as percentage or mean (standard deviation).

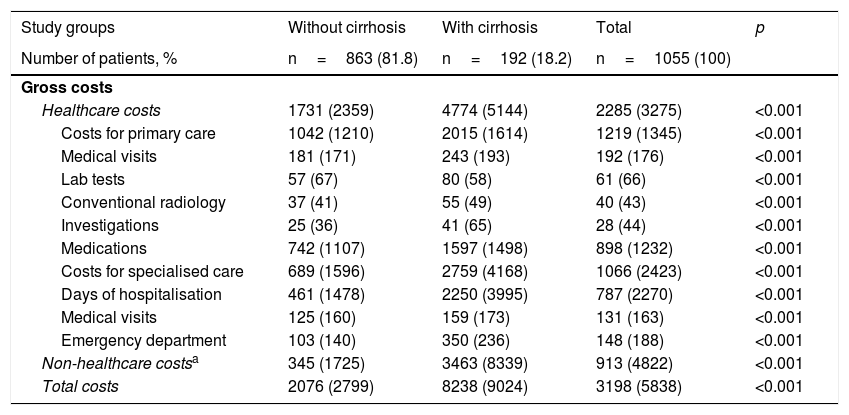

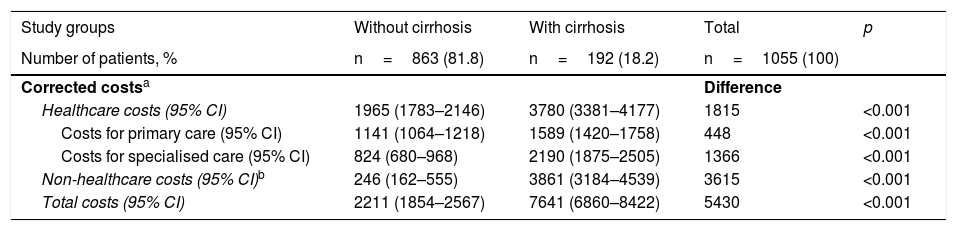

Table 5 shows the distribution of direct costs (healthcare) and indirect costs according to the presence or absence of cirrhosis. The total gross cost of all patients treated was 3.3 million euros, with 71.5% of such amount corresponding to direct costs (healthcare) and 28.5% corresponding to indirect costs. With regard to healthcare costs, 38.1% were primary care costs (medication 28.1%, medical visits 6.0%) and 33.3% were specialised care costs. The total mean cost per patient with HCV (including direct and indirect costs) was €3198. The costs for patients without cirrhosis were lower than for patients with cirrhosis (€2076 versus €8238, p<0.001). The different components of the cost also decreased proportionally. In the corrected model (ANCOVA, Table 6), these differences were maintained, with costs of €2211 (95% CI 1854–2567) versus €7641 (95% CI 6860–8422), with p<0.001 (difference of €5430 per patient), respectively.

Distribution of direct costs (healthcare) and indirect costs by study group (in euros).

| Study groups | Without cirrhosis | With cirrhosis | Total | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients, % | n=863 (81.8) | n=192 (18.2) | n=1055 (100) | |

| Gross costs | ||||

| Healthcare costs | 1731 (2359) | 4774 (5144) | 2285 (3275) | <0.001 |

| Costs for primary care | 1042 (1210) | 2015 (1614) | 1219 (1345) | <0.001 |

| Medical visits | 181 (171) | 243 (193) | 192 (176) | <0.001 |

| Lab tests | 57 (67) | 80 (58) | 61 (66) | <0.001 |

| Conventional radiology | 37 (41) | 55 (49) | 40 (43) | <0.001 |

| Investigations | 25 (36) | 41 (65) | 28 (44) | <0.001 |

| Medications | 742 (1107) | 1597 (1498) | 898 (1232) | <0.001 |

| Costs for specialised care | 689 (1596) | 2759 (4168) | 1066 (2423) | <0.001 |

| Days of hospitalisation | 461 (1478) | 2250 (3995) | 787 (2270) | <0.001 |

| Medical visits | 125 (160) | 159 (173) | 131 (163) | <0.001 |

| Emergency department | 103 (140) | 350 (236) | 148 (188) | <0.001 |

| Non-healthcare costsa | 345 (1725) | 3463 (8339) | 913 (4822) | <0.001 |

| Total costs | 2076 (2799) | 8238 (9024) | 3198 (5838) | <0.001 |

Values expressed as mean (standard deviation).

Distribution of corrected direct costs (healthcare) and indirect costs by study group (in euros).

| Study groups | Without cirrhosis | With cirrhosis | Total | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients, % | n=863 (81.8) | n=192 (18.2) | n=1055 (100) | |

| Corrected costsa | Difference | |||

| Healthcare costs (95% CI) | 1965 (1783–2146) | 3780 (3381–4177) | 1815 | <0.001 |

| Costs for primary care (95% CI) | 1141 (1064–1218) | 1589 (1420–1758) | 448 | <0.001 |

| Costs for specialised care (95% CI) | 824 (680–968) | 2190 (1875–2505) | 1366 | <0.001 |

| Non-healthcare costs (95% CI)b | 246 (162–555) | 3861 (3184–4539) | 3615 | <0.001 |

| Total costs (95% CI) | 2211 (1854–2567) | 7641 (6860–8422) | 5430 | <0.001 |

CI: Confidence interval.

Values expressed as mean (standard deviation).

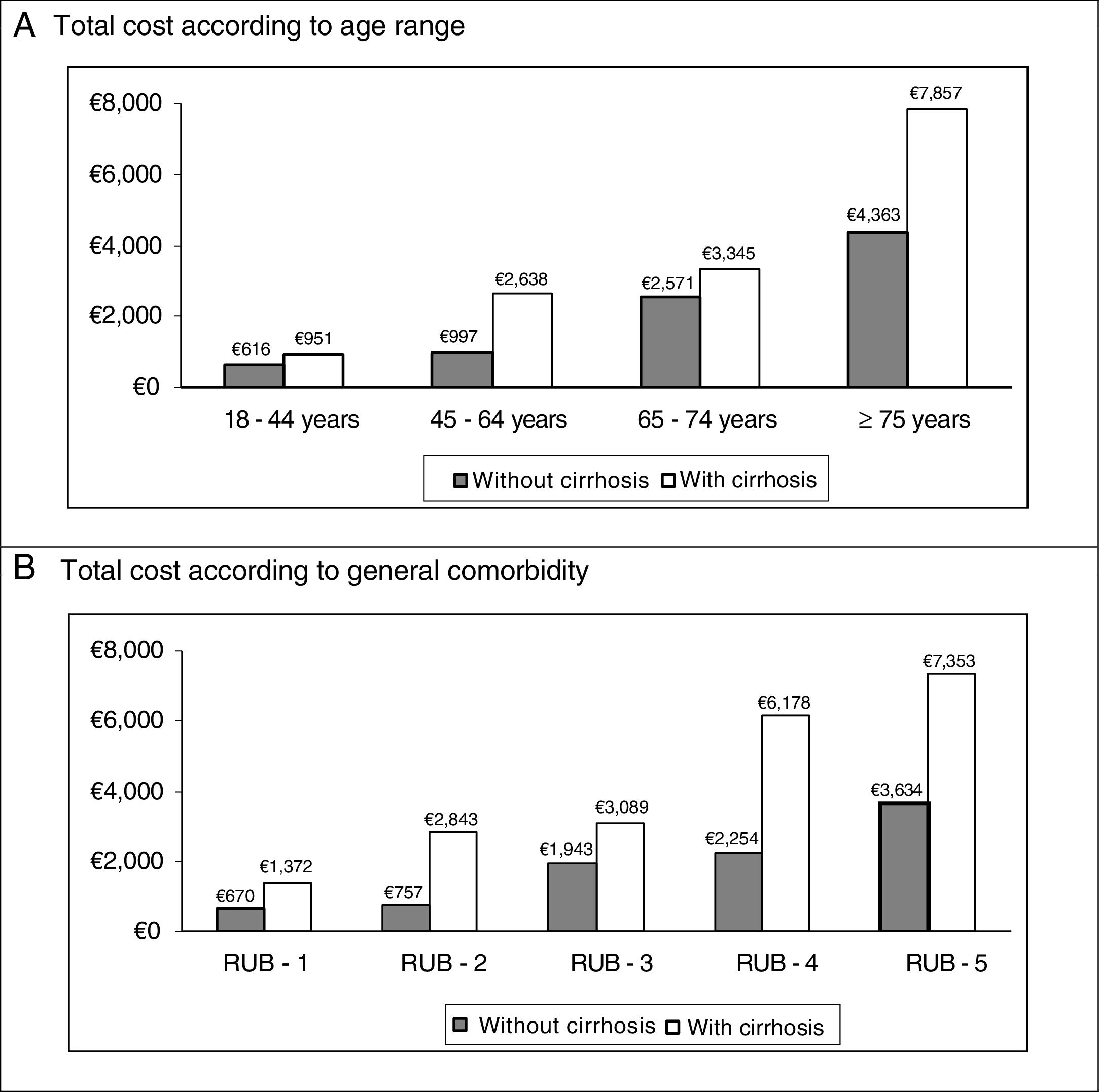

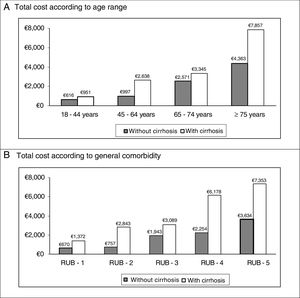

In the binary correlations, age had a direct association with general comorbidity (RUB: r=0.465; p<0.001), while direct costs (healthcare) were associated with cirrhosis (r=0.407; p<0.001), renal failure (r=0.418, p<0.001) and general comorbidity (r=0.300, p<0.001). The distribution of the total cost for the patients studied by age group and the general comorbidity in both study groups (absence/presence of cirrhosis) are shown in Fig. 2. It must be noted that a higher cost was observed in patients with cirrhosis in all the comparisons.

DiscussionThe data from our cohort of patients show that the prevalence of CHC was 1.9% and 18.2% of patients had cirrhosis. The mean time from diagnosis of CHC to inclusion in the study was 18.1 years. These results appear to be consistent with available literature.2–4 In our study, the mean patient age was slightly higher than the age reported in other references. This observation may be coincidental, or may also be due to the fact that our data are more recent, reflecting the progressive ageing of the population infected with HCV. The study results show that patients infected with HCV, and especially patients with cirrhosis, are associated with comorbidity and the use of concomitant medications, a circumstance that results in greater use of healthcare resources and higher costs for the national healthcare system. There are very few observational studies describing these variables in real-life situations, which has repercussions on the comparison of results from other references. However, one strength of the study is perhaps the fact that it is an observational, non-interventional study based on the results obtained in clinical practice and therefore provides relevant information on epidemiological, clinical and economic aspects of this group of patients. Nevertheless, it should be noted that without adequate standardisation of methodologies for measuring the variables studied, the results obtained should be interpreted with care, forcing us to be cautious about the external validity of the results.

In our study, the overall disease burden (Charlson index, RUB) related to CHC carriers was high. Cardiovascular, metabolic, mental and musculo-skeletal diseases were the most prevalent, especially in patients with cirrhosis; these results are also consistent with the references consulted.23–27 As an example, HCV is associated with a trend towards obesity. Chen et al.28 detected 28.8% of obese people in a cohort of 1118 patients with CHC; independent factors associated with obesity were age and viral load. In a randomised cohort of 1627 Spanish patients (SEEDO’97 study),29 a higher prevalence of obesity was observed in women with CHC, although the predisposition to obesity in these patients may also be related to changes in lifestyle induced by the infection. In 2 published studies, McKibben et al.30 and Serres et al.31 concluded that HCV may increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, though it should be determined whether duration of the infection or the treatment administered may influence the development of atheromatous plaque. In this aspect, cirrhosis causes insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes, but it is associated with greater comorbidity (alcohol abuse, medical illnesses and mental illnesses). Furthermore, in patients with genotype 1, hepatic steatosis is associated with factors related to the individual, such as body mass index, body fat and visceral obesity, whereas in patients with genotype 3, it is associated with viral load. Our results are similar to those reported in the consulted references,32,33 although it should be noted that in our study the genotype and retroviral treatment of these patients were not quantified and it should therefore be interpreted as a limitation of the study.

The most commonly used medications were: antiinfectives, nervous system, metabolism, musculo-skeletal system and cardiovascular system. These results are consistent with the morbidity burden of these patients, especially in subjects with cirrhosis. Lauffenburger et al.,34 in a retrospective study conducted between 2006 and 2010, observed the large amount of medication these patients are exposed to, which is a circumstance that can have repercussions in that almost half of them showed side effects and/or adverse reactions to medication. Information provided by Mohammad et al.35 and other authors6,8,9,36 follows the same line of argument as ours.

The total cost of patients with CHC was high. Healthcare costs had an independent association with time since diagnosis, cirrhosis, age, general comorbidity and diabetes. It is worth mentioning that the limited studies conducted on the cost of the disease and their variability make it difficult to compare the results obtained. This variation was mainly due to the methodology used, government fees and the specific protocols followed in each country. In the references consulted, variations in CHC costs were observed, ranging from $12,000 to $25,000. El Khoury et al.12 conducted a systematic review of the literature to identify the cost of CHC, identifying only 45 related studies. The authors concluded that hepatitis C imposes a high economic cost worldwide and it is important to separate this from the morbidity burden of patients (refractory ascites $16,740, decompensated cirrhosis $4660, diuretic-sensitive ascites $3400). Davis et al.37 assessed the cost in terms of medications and medical services in the USA for a period of 12 months after diagnosis. They analysed 20,662 patients (mean age 49 years; men 61%) and obtained a cost of $20,961 per patient-year (4 times higher than the general population). The hospitalisation rate was 24%. The conclusions of the study were that the cost of patients with CHC is high for healthcare organisations and that it is necessary to improve efforts for early detection and treatment of CHC, especially prior to progression to cirrhosis of the liver. Sapra et al.38 (n=3795, age 50.2 years; women 36.2%) also highlighted the high comorbidity (anaemia 29.2%, depression 11.5%) and average cost of these patients ($6377), not including days off work. Tandon et al.39 detail the high economic burden of the disease, which is related to the comorbidity associated with these patients. Razavi et al.40 detail the high costs associated with CHC in an interesting study. However, they also show that the prevalence of CHC is on the decline (lower incidence). Nevertheless, cases of liver disease will continue to increase, as will the costs for the relevant healthcare. Our results are difficult to compare, but generally are consistent with these studies, highlighting the association between comorbidity (cirrhosis) and cost. The indirect cost of the patients in our study may have been higher if the measurement criteria for loss of productivity provided by Eurostat (€21/h) or Eurofund (7.7h/day not worked) had been followed. However, to the best of our knowledge, these are offset by the lower wages in Spain, which are consistent with the source consulted.21

The article presents limitations typical of retrospective studies, such as under-reporting of the disease or possible variability between professionals and patients due to observational design. It should be noted that this type of design is not without bias (factors not taken into account), such as socio-economic level, cultural or education level, pharmacological doses consumed, duration of treatment, therapeutic adequacy, not having differentiated the different genotypes of patients, retroviral treatment administered, possible side effects, or classification of cirrhosis (compensated and decompensated), which should be minimised. The main objection to the study is its undoubted selection bias by the lead physician when administering one or another drug, and the external validity, so the results must be interpreted with caution. It must also be noted that the study data were obtained prior to development of the new direct-acting antivirals, which may modify some of the study results (rapid development of new molecules and their use).

To conclude, this observational cohort study found that HCV infection is associated with a high prevalence of comorbidities and use of concomitant medications, especially in patients with cirrhosis, which results in increased use of resources and costs for the Spanish National Healthcare System. On taking these findings into account, efforts to identify patients with HCV infection via adequate screening (early detection programmes) and to start effective antiviral therapy are shown as relevant priorities. It is hoped that the success of such initiatives will minimise the risk of long-term sequelae in CHC patients.

AuthorshipThe conception and design of the manuscript were the responsibility of A. Sicras and R. Navarro; data collection and statistical analysis were the responsibility of A. Sicras; and data interpretation, drafting, review and approval of the manuscript submitted were the responsibility of all authors.

Conflict of interestThe study was sponsored by Gilead Sciences. A. Sicras is an independent consultant who helped develop this manuscript. The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Sicras-Mainar A, Navarro-Artieda R, Sáez-Zafra M. Comorbilidad, medicación concomitante, uso de recursos y costes sanitarios asociados a los pacientes portadores del virus de la hepatitis C crónica en España. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:234–244.