Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection may present as reactivation of a latent infection or as primary infection. In patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), reactivation is more common and usually presents in a context of severe cortico-refractory flare-ups of ulcerative colitis (UC).1,2 Although primary infection is less common, it may have more serious consequences3 and its management may be more complex, especially in immunosuppressed patients. Below we present 2 cases of primary CMV infection in patients with IBD.

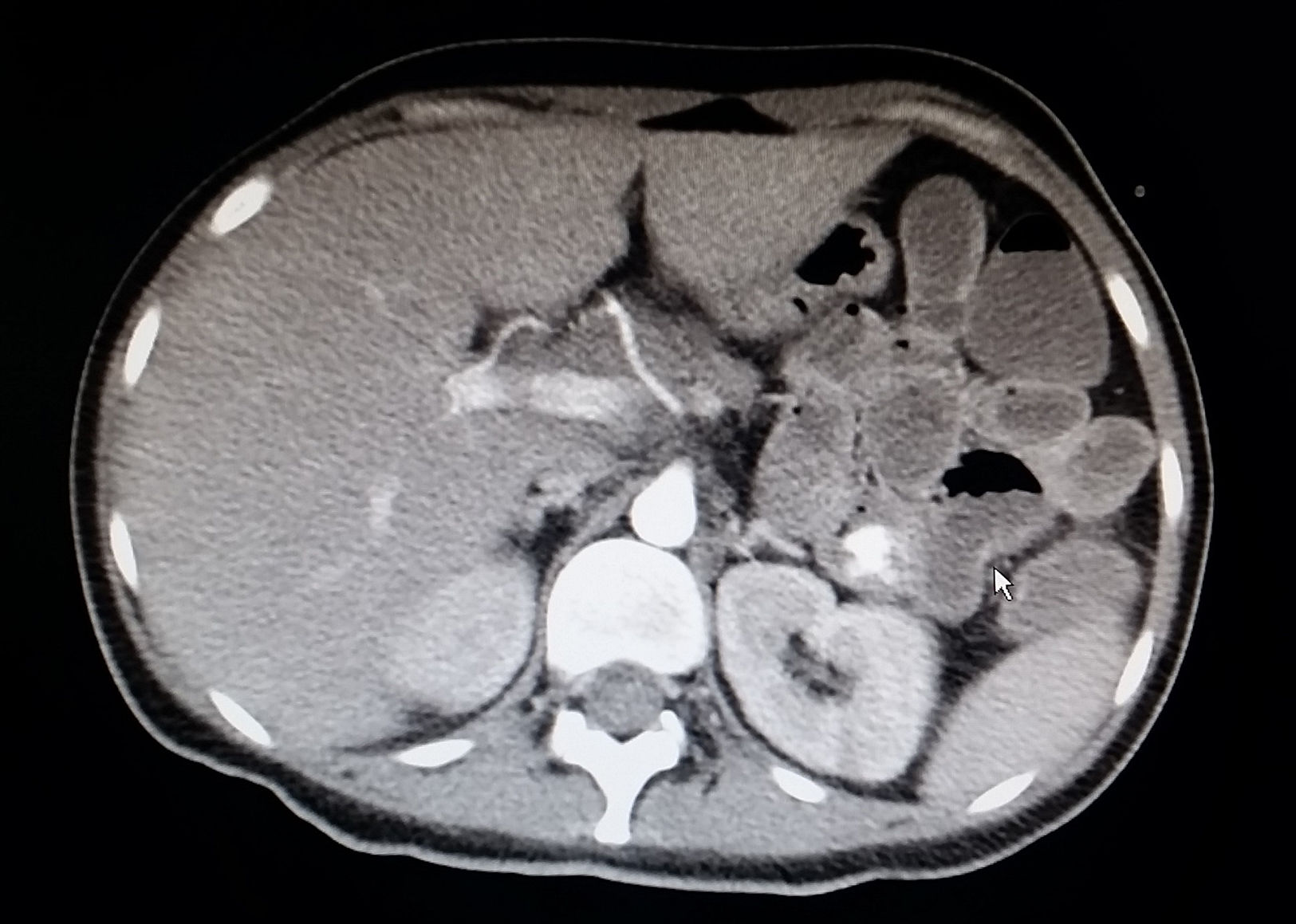

Case 1A 30-year-old woman having been diagnosed 5 years earlier with distal UC was being treated with mesalazine and azathioprine started due to cortico-dependence 4 years later. She was admitted to our unit, having been referred from another centre due to a severe cortico-refractory flare-up associated with fever and leukopenia. On admission, the patient was having 15 bowel movements per day with traces of blood, and pain in her left flank. Laboratory testing revealed pancytopenia (haemoglobin 7.3g/dl, neutrophils 600 × 106/l, platelets 102,000 × 106/l), hypoalbuminaemia (23.6g/l), elevated acute phase reactants (C-reactive protein [CRP] 123mg/dl and faecal calprotectin 4236mg/kg) and a normal liver panel. Rectoscopy showed an erythematous mucosa with deep “geographic” ulcers. These ulcers were biopsied. As CMV infection was strongly suspected, treatment was started with intravenous cyclosporine and ganciclovir. Transfusion support, colony-stimulating factor, antibiotic coverage and enteral nutrition were started as well. CMV serology was negative for IgG and positive for IgM, with a viral load (VL) of 16,923copies, and the rectal biopsies revealed CMV through immunohistochemistry, thereby confirming a diagnosis of primary CMV infection affecting the bowel. Chorioretinitis and HIV infection were ruled out. Given the persistence of fever and pancytopenia, despite an improvement in gastrointestinal signs and symptoms and a decrease in CRP, ganciclovir was replaced with foscarnet and bone marrow aspiration ruled out haemophagocytosis. Following initial clinical improvement, the patient had an episode of haematemesis without haemodynamic instability secondary to duodenal ulcers due to CMV (according to biopsy) verified on emergency gastroscopy. Subsequently, she had an episode of persistent rectal bleeding with haemodynamic instability requiring mechanical ventilation and haemodynamic support with amines. An angiogram confirmed active bleeding in the proximal jejunum which subsided following embolisation (Figs. 1 and 2). Treatment with cyclosporine was maintained until the patient developed hypertension a few days prior to discharge, and infliximab was started as maintenance treatment. On discharge, valganciclovir (900mg/12h) was started and maintained until the VL became negative. At this point, azathioprine was restarted due to a risk of macrophage activation syndrome (MAS).

A 24-year-old man had been diagnosed with colic Crohn's disease 8 years earlier and treated with azathioprine and adalimumab due to concomitant perianal disease. He was admitted due to fever for the past week associated with an increased number of bowel movements with occasional traces of blood and an abnormal liver panel (AST 127U/l, ALT 130U/l). A physical examination revealed inguinal and supraclavicular lymphadenopathy measuring a millimetre. Serologies for viral hepatitis and HIV, blood cultures, urine culture, faecal culture, and determination of C. difficile toxin were negative. A CT scan of the chest and abdomen ruled out lymphoproliferative impairment and ileocolonoscopy ruled out CD activity. During admission, his diarrhoea spontaneously remitted, whereas his fever and liver abnormalities persisted for several days with no other associated symptoms. Finally, serology enabled a diagnosis of primary CMV infection (positive for IgM, negative for IgG and a VL of 23,000copies). Treatment with intravenous ganciclovir was started and maintained for 12 days, and immunosuppression was suspended. The patient followed a good clinical course with good laboratory values. Subsequently, treatment was started with valganciclovir until the VL became negative, and the prior immunosuppression was reintroduced.

Primary CMV infection is generally asymptomatic or may present as a syndrome similar to mononucleosis.1 Some 65%-90% of the adult population is seropositive for IgG-CMV.4 Therefore, symptomatic primary infections in adults are very uncommon. However, disseminated forms have been reported in immunosuppressed patients. In this situation, the organs of the gastrointestinal tract are most commonly affected.5 In patients with IBD, interest in CMV has been focused on its local reactivation in the colon in patients with cortico-refractory UC. However, in immunosuppressed patients (especially those on thiopurines),6–10 primary CMV infection may constitute a true opportunistic infection and represent the most common precipitating factor associated with the development of MAS in these patients.3 In the 2 cases presented above, primary CMV infection behaved as a serious opportunistic infection leading to hospital admission and specific treatment. In one of them, it was life-threatening and required bone marrow aspiration to rule out MAS. However, in patients with IBD who present persistent fever and are being treated with anti-TNF or thiopurines there is a tendency to look for intracellular pathogens (tuberculosis, Listeria, Histoplasma, etc.). The importance of the cases presented lies in the need to consider this diagnosis (beyond the colic reactivation usually considered in IBD) in immunosuppressed patients with IBD. Finally, it should be noted that, in both cases, treatment with anti-TNF, as well as thiopurine treatment, were restarted or established.

Please cite this article as: Torres P, Lobatón T, Cañete F, Clos A, Mañosa M, Cabré E, et al. Primoinfección por citomegalovirus en enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:453–454.