The presence of air in regions of the abdomen may be due to 2 diseases: gastric emphysema and emphysematous gastritis, which differ in aetiology, clinical presentation, evolution and prognosis.1,2

Gastric emphysema was described by Brouardel in 1985 as a generally benign disease caused by disruption of the gastric mucosa and subsequent infiltration of the mucosa by air. It is usually a self-limiting disease and resolves without sequelae.2

Emphysematous gastritis is a rare and severe gas-forming infection in the gastric wall. It is caused by the disruption of the mucosa and subsequent invasion of the gastric wall by gas-forming bacteria. This results in acute suppurative inflammation of the wall that compromises the submucosa and muscle layer, with the formation of abscesses, necrosis and marked leucocyte infiltration.3 Incidence has increased, associated with immunodeficiency syndromes. Aetiology may differ, but a common factor in all cases is increased intragastric pressure caused by, for example, nasogastric intubation, hyperemesis, acute pancreatitis, duodenal obstruction, use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, peptic ulcer, alcoholism, acids and alkalis, high dose dexamethasone therapy, instrumentation of the upper gastrointestinal tract, general anaesthesia, and cardiac resuscitation. It may also be associated with recent surgery, trauma, haemodialysis, malignant neoplasms, extensive burns, and gastric infarction.4

The diagnostic method of choice is computed tomography (CT), while the preferred treatment is antibiotic therapy and surgery when medical treatment fails. Due to its initial non-specific symptoms and rare occurrence, diagnosis is usually late and the disease often progresses to severe peritonitis with a very poor prognosis.

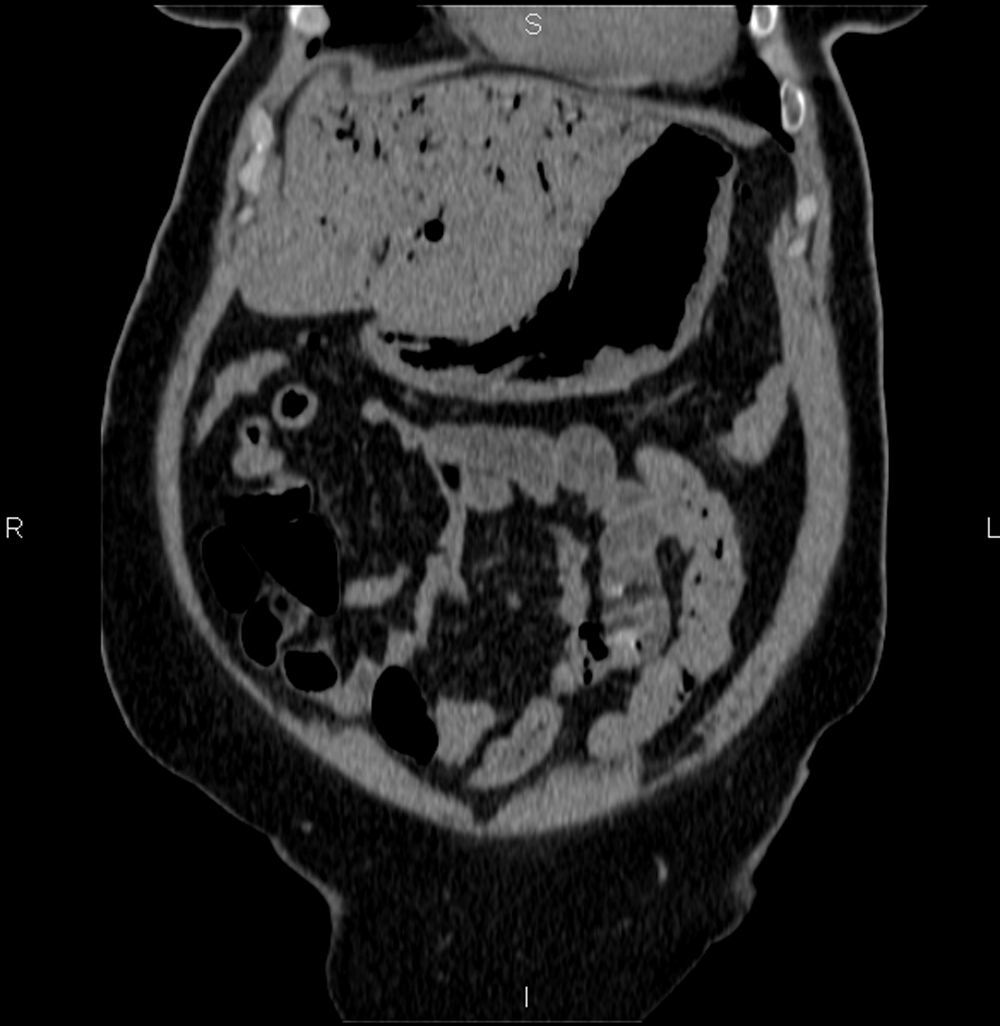

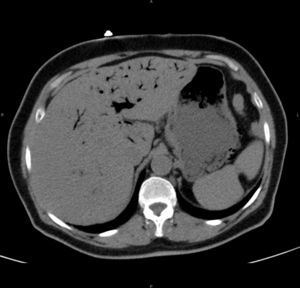

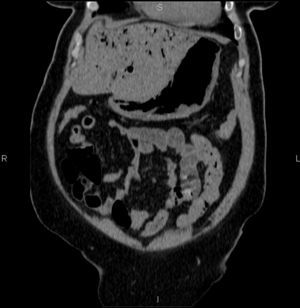

We present the case of a 75-year-old woman with a history of high blood pressure, non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus, rheumatic valvular heart disease with mitral valve replacement by a metal stent and tricuspid ring, and moderate/severe aortic stenosis. She reported a 4-month history of diarrhoea, which in the last month was accompanied by vomiting after meals. Five days previously, she presented a new episode of diarrhoea without fever, accompanied by intense epigastric pain irradiating to the back, associated with vomiting and general malaise. In the emergency department, the patient remained hypotensive, with metabolic acidosis. An urgent abdominal CT scan without contrast revealed emphysematous gastritis and gas in the intrahepatic bile duct (Figs. 1 and 2). Fibre-optic endoscopy showed haemorrhagic gastritis. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) and started on treatment with metronizadole and piperacillin-tazobactam, proton pump inhibitors, fluid therapy and total parenteral nutrition. In the ICU, the patient remained haemodynamically stable and did not require vasoactive support. She presented progressive mixed inflammatory/iron deficiency anaemia, for which she received treatment with intravenous iron and vitamin B complex. On the fourth day of admission, right basal consolidation was observed on the chest radiograph. Epigastric and right upper quadrant pain gradually subsided during her stay in the ICU. A follow-up CT scan on the sixth day of admission showed that the cystic pneumatosis of the gastric wall had resolved, but gas remained in the hepatic portal system. Results of blood cultures, urine cultures and sputum culture taken from the patient on admission were negative, while pathological study of the gastric biopsy found histological changes on the base of the ulcer with a small number of bacilli consistent with Helicobacter pylori. Given the patient's good progress (and once she was able to tolerate food and liquid by mouth), she was discharged to internal medicine on the 12th day of admission.

This entity was first described by Galen, who named it “erysipelatous tumour of the stomach”.5 Decreased acidity or presence of lesions in the gastric mucosa could permit bacterial colonization of the gastric wall. Another mechanism involves dissemination of the bacteria through the blood from a distant septic focus.5,6 However, the port of entry is often unknown,6 as in our patient. Gastric mucosa involvement can be superficial gastritis, necrotic gastritis, pangastritis or emphysematous gastritis. The latter is serious and the least common, and is characterized by the formation of abscesses in the gastric wall (especially in the submucosa), with a tendency to open into the gastric cavity and form gastric cellulitis that can spread to the peritoneal cavity, producing secondary peritonitis. There may be associated spontaneous pneumoperitoneum and air in the portal vein and its intrahepatic lobar or segmented branches. The existence of gas in the portal territory was previously an indication for primary surgery, but due to poor outcomes, early antibiotic treatment is currently preferred2; the case of our patient is an example of the presence of gas in the portal territory and favourable progress with antibiotic treatment without requiring surgery.

The microorganisms most frequently isolated are group A β-haemolytic streptococcus (Streptococcus pyogenes), staphylococcus (Staphylococcus aureus) and Escherichia coli. Other pathogens found are Enterobacter cloacae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Clostridium perfringens and welchii and Klebsiella pneumoniae.1,5,6

Initial symptoms are very non-specific: abdominal pain, diarrhoea, nausea, vomiting and fever, so early diagnosis is very difficult. In some cases, the clinical presentation is septic shock, although in other cases–like our patient–the presentation is sepsis. Diagnosis is by plain abdominal X-ray and/or abdominal CT scan. In addition to detecting the presence of gas in the abdominal wall, CT can also reveal gastric wall thickening.5 Less often, diagnosis is made by upper gastrointestinal fibre-optic endoscopy with biopsy sampling.

Current treatment should include antibiotics that cover Gram negative, Gram positive and anaerobic bacteria. Gastric acid secretion inhibitors, fluid therapy and parenteral nutrition should also be added.7 Surgery should be considered in the event that medical treatment fails or complications such as gastric perforation arise. Prompt diagnosis followed by appropriate antibiotic treatment improves the prognosis. Ideally, these patients should be monitored in ICUs. According to published case series, mortality is greater than 60%.8,9

If the patient progresses well, healing occurs with hyperplasia of the conjunctive tissue and residual fibrosis, or chronic cirrhotic gastritis that resembles Brinton linitis plastica in appearance and general characteristics.3

In conclusion, phlegmonous gastritis is a rare, rapidly progressive and potentially fatal bacterial infection of the gastric wall; in some cases, such as our patient, early antibiotic treatment can be curative, thus improving survival rates.

Please cite this article as: Zamora Elson M, Labarta Monzón L, Escos Orta J, Cambra Fierro P, Vernal Monteverde V, Seron Arbeloa C. Gastritis enfisematosa, eficacia del tratamiento con antibioterapia precoz. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:393–395.