To show the importance of the differential diagnosis between emphysematous gastritis (EG) and gastric emphysema (GE), we present two cases of gastric pneumatosis (GP) that required different therapeutic approaches.

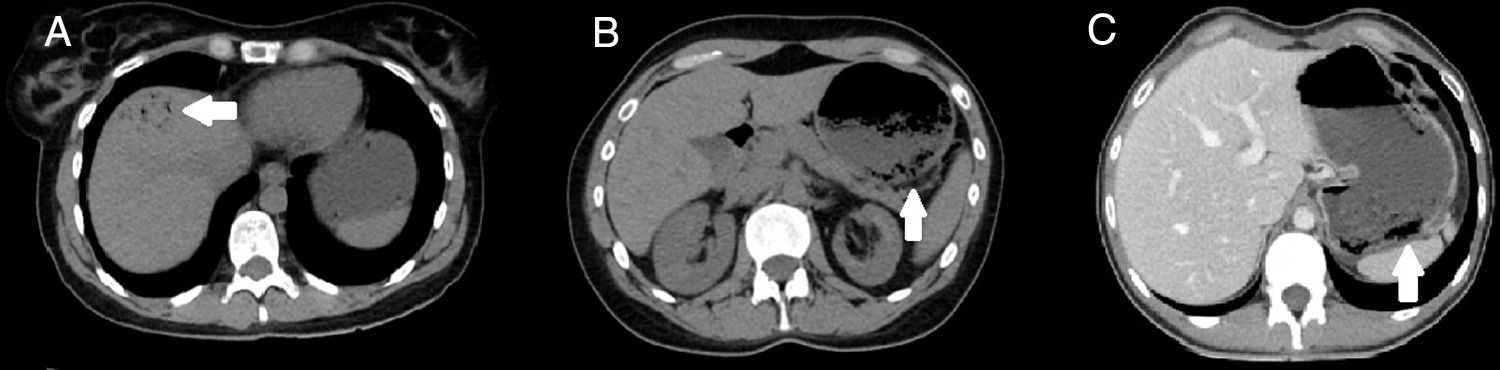

A 34-year-old female with a history of endometriosis presented with abdominal pain and vomiting for 24 h. Her abdominal pain was accompanied by signs of peritonism and blood tests showed leukocytosis with neutrophilia. CT showed necrosis with gastric pneumatosis and portal pneumatosis (Fig. 1A and B). The acute abdomen and blood test results along with the radiological suspicion of emphysematous gastritis led to the decision for emergency surgery. As diagnostic laparotomy showed no evidence of intra-abdominal abnormalities, an intraoperative gastroscopy was performed, which revealed necrosis of the gastric mucosa without transmural involvement. No additional surgical procedures were performed. Endoscopic samples were taken for histological and microbiological analysis, with negative cultures and normal histology. The patient made satisfactory progress with broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, and was discharged on day 7 after surgery. In the end, she was diagnosed with EG, with negative cultures and no clear precipitating cause.

A 25-year-old female with diabetes presented with 48 h of abdominal pain associated with copious vomiting. She had abdominal pain, but no peritonism or abnormal lab test results. CT showed gastric pneumatosis without portal pneumatosis (Fig. 1C). Gastric emphysema caused by increased intragastric pressure was suspected, and she was started on conservative medical treatment with fluid therapy, nil by mouth, nasogastric (NG) tube and proton pump inhibitors (PPI). The subsequent gastroscopy showed erosive gastritis, with normal histology and negative microbiology. The patient made good clinical progress and was discharged on day 3 with the diagnosis of GE.

EG and GE are two diseases with different aetiology, symptoms, treatment and prognosis. However, because of the similarity in the radiological findings, the differential diagnosis is complex. The presence of GP is typical in both conditions.1–3

EG is a serious infection induced by gas-producing microorganisms which invade the wall and cause inflammation, with the development of necrosis, abscesses and leukocyte invasion. Some of the typical causal germs are Streptococcus spp., Enterobacter spp., Clostridium spp., S. aureus, P. aeruginosa and Candida spp.1 However, as with our patient, in a high percentage of cases it is not possible to isolate the germ responsible.

Risk factors for EG include ingestion of caustic substances, vomiting, gastric distension, cancer, recent surgery and treatment with NSAID, corticosteroids or chemotherapy. The common precipitating factor is gastric mucosal injury due to hyperpressure and subsequent colonisation by infectious agents.2

Meanwhile, GE is defined as the presence of gas in the stomach walls caused by disruption of the mucosa and subsequent dissection of air into the wall. Instrument-related iatrogenic trauma to the mucosa (by intubation or endoscopy) is the predominant cause.2 In our case, the precipitating factor was the increase in endoluminal pressure associated with vomiting.

The initial symptoms in both conditions are nonspecific (nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, etc.), which makes the diagnosis more complex. However, fever and systemic involvement tend to be more common in EG, while GE is generally asymptomatic or causes few symptoms.1–3

The presence of gastric pneumatosis on CT is a typical feature of both disorders, while gastric wall thickening and portal pneumatosis are findings suggestive of EG. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy enables the gastric mucosa to be viewed and samples to be taken for histological and/or microbiological analysis.3

An accurate differential diagnosis is important due to the differences in treatment approach and outcome. EG has a high mortality rate and requires broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy (with coverage of Gram-negative, Gram-positive and anaerobic germs), fluid therapy, and sometimes emergency surgery (where conservative treatment fails or in cases of suspected complications, such as transmural necrosis or perforation). In our case, surgery was required at the outset due to a suspected complication. GE, in contrast, is generally self-limiting with conservative treatment (nil by mouth, gastric decompression with NG tube, PPI, fluid therapy and analgesia).4,5

FundingNo funding was received for this study.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Garrosa-Muñoz S, López-Sánchez J, Muñoz-Bellvís L. Enfisema gástrico y gastritis enfisematosa, entidades aparentemente similares con tratamiento muy diferente. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;44:366–367.