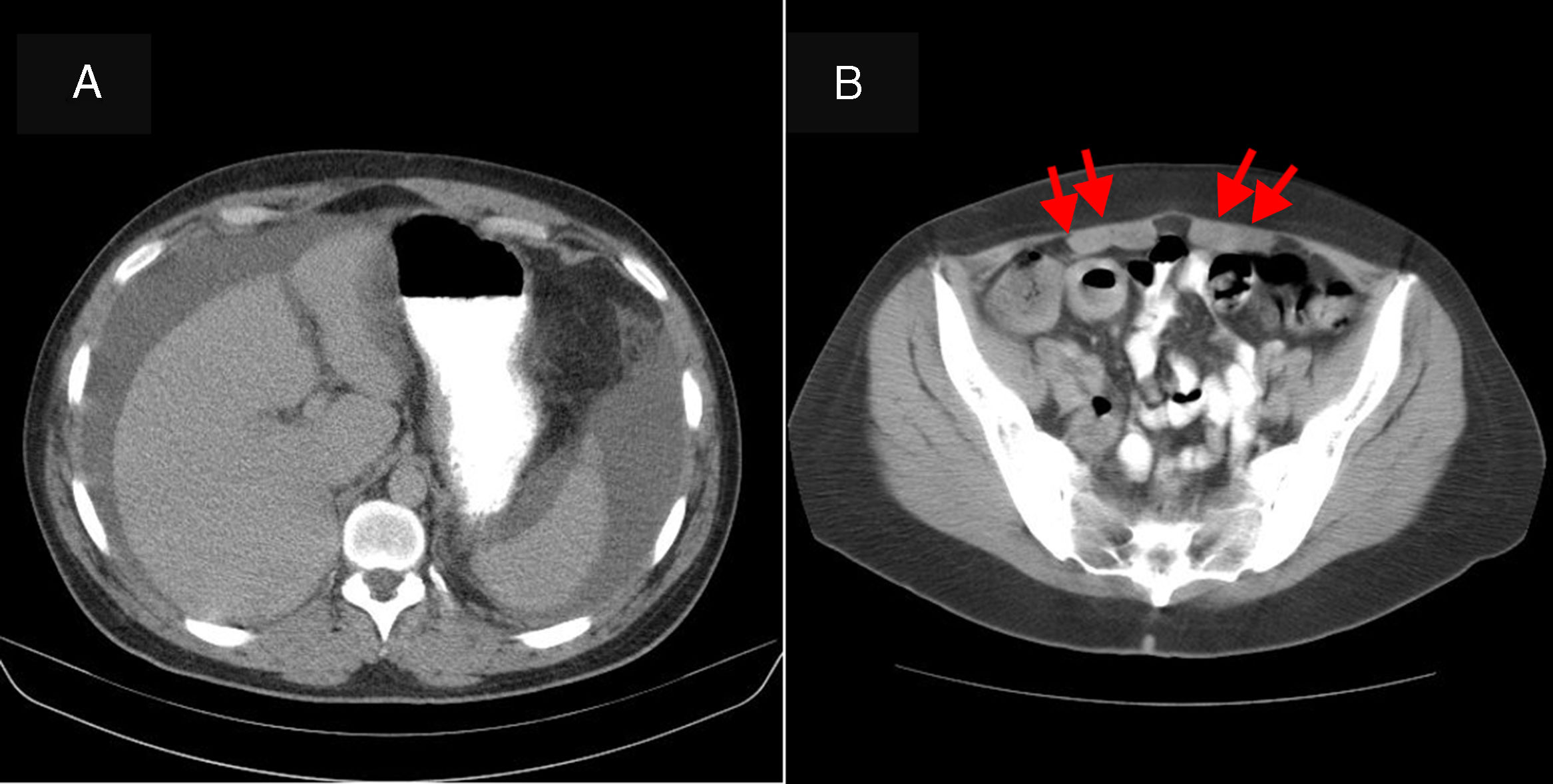

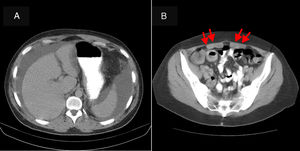

A 35-year-old man with a history of atopic rhinitis was admitted due to hypogastric abdominal pain for the past 20 days and gradual abdominal distension. He had no associated diarrhoea or other symptoms. He denied having consumed alcohol or other toxic substances. On physical examination he was found to be afebrile with a distended abdomen and dullness on both flanks, suggestive of ascites. Blood testing revealed: leukocytes 9930/μl, eosinophils 29.9% and no immature forms of myeloid cells. The rest of the complete blood count, amylase, the liver panel, total proteins, albumin, TSH and clotting were normal. A chest X-ray was also normal. An abdominal ultrasound with Doppler showed abundant free peritoneal fluid. The liver, splenoportal axis, pancreas and spleen as well as the rest of the examination were normal. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed a moderate amount of ascites and thickening of the abdominal mesenteric fat suggestive of oedema (Fig. 1). Diagnostic paracentesis revealed: cytology study with 95% eosinophils, with no evidence of malignant cells; adenosine deaminase (ADA) <40U/l; culture negative; seroalbumin gradient <1. A study of the usual parasites in faeces came back negative in 3 determinations. The patient did not report having travelled to any area endemic for parasitic infections. As eosinophilic gastroenteritis (EGE) was suspected, gastroscopy was ordered. This showed a normal oesophagus, stomach and duodenum (biopsies by normal segments) as well as normal intestinal transit. A PET-CT scan performed to screen for tumour disease ruled out metabolic abnormalities consistent with peritoneal carcinomatosis. It showed several lymph node formations of non-pathological size and metabolism in a mesentery with a reactive appearance. The study was completed with the following peripheral blood determinations: adenosine deaminase (ADA) normal; C1-inhibitor normal; Anisakis IgE negative; serology for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatotropic viruses negative; anti-smooth muscle antibodies (ASMAs) 1/640; antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs), antimitochondrial antibodies, antinuclear antibodies and anti-transglutaminase antibodies negative; and serum tryptase negative. A Mantoux test came back negative. With a suspected diagnosis of eosinophilic ascites and other causes of eosinophilia having been ruled out, treatment was started with 25mg of prednisone. A decrease in the patient's ascites was verified within a week. After 2 months, the patient's symptoms had completely disappeared.

EGE is an uncommon entity characterised by infiltration of eosinophils in any segment of the gastrointestinal wall, capable of affecting any layer, in the absence of other causes of eosinophilia.1

There are 3 different disease types depending on the layer of the gastrointestinal wall that is affected. Mucosal impairment is the most common type (70%). It manifests as iron-deficiency anaemia, enteropathy, protein loss or malabsorption. Predominately muscular impairment (20%) is characterised by localised or diffuse thickening of the abdominal wall and is capable of causing obstructive symptoms. Finally, subserous impairment (10%) features ascites rich in eosinophils or, in severe cases, peritonitis, perforation or intestinal intussusception.2 Other less common forms of presentation are obstructive jaundice due to biliary tract impairment and extraintestinal manifestations such as eosinophilic cystitis, eosinophilic splenitis and eosinophilic hepatitis.

Talley et al. identified 3 diagnostic criteria for EGE: (1) gastrointestinal symptoms; (2) gastrointestinal tract biopsies showing eosinophilic infiltration or radiological characteristics with peripheral eosinophilia or ascites rich in eosinophils; and (3) absence of parasitic or extraintestinal disease.3 Although peripheral eosinophilia is present in most patients, it is present at even higher rates in subserous forms. It may be absent in 30% of cases.

Among patients with EGE, 50% have a concomitant allergic disorder (asthma, rhinitis or a food or drug intolerance).4 This suggests that EGE may result from immune deregulation in response to an allergic reaction. Parasitic infestation and drugs may also act as triggers.

Diagnosis of subserous EGE may be complicated due to its rarity and the non-specific nature of its signs and symptoms. The most common symptoms are: abdominal pain (90.45%), nausea and vomiting (57.1%), diarrhoea (52.3%), and abdominal distension (38.1%).5 Eosinophilic ascites should be suspected in all patients with abdominal pain, ascites and peripheral hypereosinophilia.6,7 The key to diagnosis is confirmation of ascitic fluid rich in eosinophils. Diagnosis requires ruling out parasitic diseases, abdominal tuberculosis, rupture of a hydatid cyst, chronic pancreatitis, vasculitis (Churg–Strauss), hypereosinophilic syndrome, malignancy and Crohn's disease.8

The overall prognosis for eosinophilic ascites is good, with an excellent response to oral steroids as a first line of treatment. It is advisable to start with prednisone 20–40mg per day. This achieves remission of symptoms in 80% of patients within a week and returns eosinophil counts to normal within 2 weeks. However, recurrence may be seen in 50% of patients when treatment is suspended.1 Surgery is reserved for the few cases with obstructive complications.

As eosinophilic ascites represents the most unusual variety of EGE, and due to the non-specific nature of its symptoms and the potential absence of both peripheral eosinophilia and infiltration of eosinophils in the gastrointestinal wall, diagnosis represents quite a challenge for the gastroenterologist and requires a high degree of suspicion.

Please cite this article as: Martín-Lagos Maldonado A, Alcazar Jaén LM, Benavente Fernández A. Ascitis eosinofílica: a propósito de un caso. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:372–374.