The incidence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) is increasing worldwide.

ObjectivesTo evaluate the incidence of IBD in Castilla y León describing clinical characteristics of the patients at diagnosis, the type of treatment received and their clinical course during the first year.

Materials and methodsProspective, multicenter and population-based incidence cohort study. Patients aged>18 years diagnosed during 2017 with IBD (Crohn’s disease [CD], ulcerative colitis [UC] and indeterminate colitis [IC]) were included from 8 hospitals in Castilla y León. Epidemiological, clinical, and therapeutic variables were registered. The global incidence and disease incidence were calculated.

Results290 patients were diagnosed with IBD (54.5% UC, 45.2% CD, and 0.3% IC), with a median follow-up of 9 months (range 8-11). The incidence rate of IBD in Castilla y Leon in 2017 was 16.6 cases per 10.000 inhabitants-year (9/105 UC cases and 7.5/105 CD cases), with a UC/CD ratio of 1.2:1. Use of systemic corticosteroids (47% vs. 30% p=0.002), immunomodulatory therapy (81% vs. 19%; p=0.000), biological therapy (29% vs. 8%; p=0.000), and surgery (11% vs. 2%; p=0.000) were significatively higher among patients with CD comparing with those with UC.

ConclusionsThe incidence of patients with UC in our population increases while the incidence of patients with CD remains stable. Patients with CD presents a worse natural history of the disease (use of corticosteroids, immunomodulatory therapy, biological therapy and surgery) compared to patients with UC in the first year of follow-up.

La incidencia de la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII) está aumentando en todo el mundo.

ObjetivosEvaluar la incidencia de EII en la Comunidad Autónoma de Castilla y León y describir las características clínicas de los pacientes al diagnóstico, el tipo de tratamiento recibido y la evolución clínica durante el primer año.

Material y métodosEstudio prospectivo, multicéntrico y poblacional en el que se incluyeron pacientes adultos diagnosticados de EII (enfermedad de Crohn [EC], colitis ulcerosa [CU] o colitis indeterminada [CI] durante el año 2017 procedentes de 8 centros de Castilla y León. Se incluyeron variables epidemiológicas, clínicas y terapéuticas. Se calculó la incidencia global y por enfermedades.

ResultadosDoscientos noeventa pacientes fueron diagnosticados de EII (54,5% de CU, 45.2% de EC y 0,3% de CI), con una mediana de seguimiento de 9 meses (rango 8–11). La tasa de incidencia fue de 16.6 casos/100.000 habitantes-año (9/105 casos de CU y 7.5/105 casos de EC), con una proporción CU/EC de 1,2:1. Los pacientes con EC recibieron significativamente más corticoides sistémicos (47% vs. 30% p=0.002), más tratamiento inmunomodulador (81% vs. 19% p=0.000), más tratamiento biológico (29% vs. 8% p=0.000) y mayor necesidad de cirugía (11% vs. 2% p=0.000).

ConclusionesLa incidencia de pacientes con CU en nuestro medio se incrementa mientras que la de EC se mantiene estable, con una historia natural de la enfermedad peor (uso de corticoides, inmunosupresores, biológicos y cirugía) para los pacientes con EC comparado con los pacientes con CU en el primer año de seguimiento.

Ulcerative colitis (UC)1 was first described in 1875, and 57 years later Crohn's disease (CD)2 was included together with indeterminate colitis (IC) in the group of conditions collectively known as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Currently, IBD is a global health problem that affects approximately 2.4 million people in Europe and 1.3 million in the United States.3

These diseases are the result of an altered immune response in a situation of intestinal dysbiosis, which is influenced by environmental factors in genetically predisposed individuals,4 and their incidence is increasing globally, particularly in western countries (USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Western Europe),5 coinciding with population growth and industrial and economic development, with prevalence figures of 1 in 200–300 inhabitants in developed countries.6,7 Meanwhile, new cases of IBD are appearing in developing countries, where the presence of these diseases was non-existent.3,6,7

Spain is the country that has published the largest number of prospective and population-based incidence studies, with figures similar to those reported in the rest of the European countries (5–12 cases of UC/100,000 inhabitants/year and 3.5–9.5 cases/100,000 inhabitants/year for patients with CD).4

Our primary objective was, based on the data collected prospectively at the national level for the EPIDEM-IBD registry that has just been published,8,9 to calculate the incidence of IBD in the community of Castile and León. Our secondary objectives were to describe the clinical characteristics of the patients at diagnosis, to evaluate the type of treatment received (immunosuppressive and/or biologic drugs and surgery), as well as the clinical course during the first year of disease progression from diagnosis.

Material and methodsA prospective, multicentre, population-based study including all patients over 18 years of age diagnosed with IBD (CD, UC or IC) from 1 January 2017 to 31 December 2017 in the autonomous community of Castile and León, with the participation of eight hospitals from five provinces of the community (Valladolid: Hospital Universitario Río Hortega [Río Hortega University Hospital], Hospital Clínico Universitario [University Clinical Hospital] and Hospital Medina del Campo [Medina del Campo Hospital]; Burgos: Hospital Universitario [University Hospital] and Hospital Santos Reyes de Aranda de Duero [Santos Reyes de Aranda de Duero Hospital]; Complejo Asistencial Universitario de León [León University Healthcare Complex], Hospital Universitario de Salamanca [Salamanca University Hospital] and Hospital Virgen de la Concha [Virgen de la Concha Hospital] in Zamora), with a total population of 1,745,988 inhabitants in that year and a mean follow-up of nine months (range 8−11).10 In Spain, the health system is public, with only 15% of patients having private insurance, and of these, only 15% do not use the public system, so it was decided at the national level not to include these patients, given that they would not significantly modify the incidence results.11

Incident cases of IBD in the different hospitals were included prospectively, checking the endoscopy, pathology and radiology databases in order to avoid losing cases. Subsequently, a visit was made at three months and at one year.

The following variables were collected using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap),12 with the permission of the Spanish Association of Gastroenterology (www.aegastro.es), a non-profit society:

- -

Sex and age.

- -

Diagnosis of IBD following the guidelines of the European Crohn's and Colitis organisation (ECCO) and the European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (ESGAR).13,14

- -

Phenotype and extension according to the Montreal classification.15

- -

Time elapsed until diagnosis: time from the patient's first symptomatic consultation with their doctor until the diagnosis was established.

- -

Smoking habit: a smoker was defined as a patient who smoked more than seven cigarettes a week for at least six months prior to diagnosis and had smoked at least one cigarette in the six months prior to diagnosis; an ex-smoker was a patient who had stopped smoking for at least six months prior to diagnosis, and a non-smoker was a patient who had never smoked or only smoked very sporadically.

- -

First-degree family history of IBD.

- -

Prior appendectomy.

- -

Extraintestinal manifestations.

- -

Pharmacological treatments received since IBD diagnosis:

- o

Mesalazine.

- o

Corticosteroids: systemic, topical or rectal.

- o

Immunosuppressive drugs: azathioprine, mercaptopurine and methotrexate.

- o

Biologics: infliximab, adalimumab, ustekinumab, and vedolizumab.

- o

- -

Surgery at diagnosis or during follow-up.

- -

Hospitalisation and reasons for admission.

To carry out the statistical analysis, the data was processed using the statistical software IBM SPSS 22. A descriptive analysis of the sample was performed, providing medians (interquartile range) and frequency (percentage) according to the type of variable. A comparative analysis was carried out between both diseases (UC vs. CD), evaluating epidemiological and clinical data and types of treatment. Depending on the type of variables, either the Mann–Whitney U test or the chi-square test (Fisher) were used. To calculate the incidence per 100,000 inhabitants, data from the National Statistics System were used for the reference population, using this data as the denominator. In addition, the age-standardised rate adjusted to the European population was calculated.

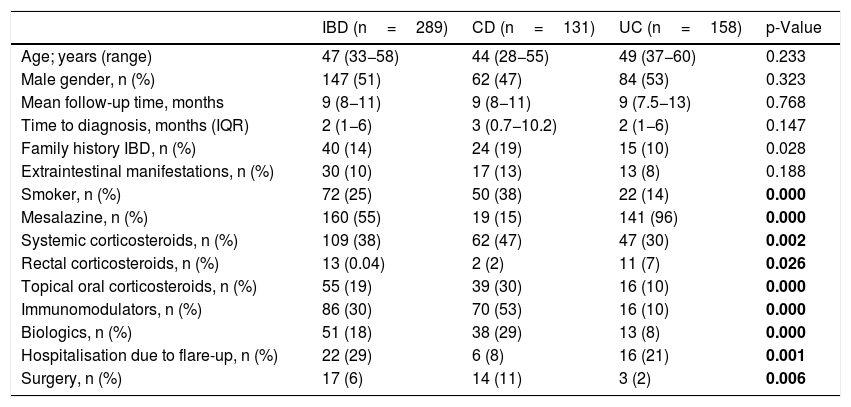

ResultsDuring the inclusion period (12 months) a total of 290 patients were diagnosed with IBD. Of these, 158 patients (54.5%) were diagnosed with UC, 131 (45.2%) with CD and one (0.3%) with IC, with a median follow-up of nine months (range 8–11 months); 51% were male (147), with a mean age of 47 years (33–58). The epidemiological data are summarised in Table 1.

Descriptive and comparative demographic variables of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis.

| IBD (n=289) | CD (n=131) | UC (n=158) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age; years (range) | 47 (33−58) | 44 (28−55) | 49 (37−60) | 0.233 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 147 (51) | 62 (47) | 84 (53) | 0.323 |

| Mean follow-up time, months | 9 (8−11) | 9 (8−11) | 9 (7.5−13) | 0.768 |

| Time to diagnosis, months (IQR) | 2 (1−6) | 3 (0.7−10.2) | 2 (1−6) | 0.147 |

| Family history IBD, n (%) | 40 (14) | 24 (19) | 15 (10) | 0.028 |

| Extraintestinal manifestations, n (%) | 30 (10) | 17 (13) | 13 (8) | 0.188 |

| Smoker, n (%) | 72 (25) | 50 (38) | 22 (14) | 0.000 |

| Mesalazine, n (%) | 160 (55) | 19 (15) | 141 (96) | 0.000 |

| Systemic corticosteroids, n (%) | 109 (38) | 62 (47) | 47 (30) | 0.002 |

| Rectal corticosteroids, n (%) | 13 (0.04) | 2 (2) | 11 (7) | 0.026 |

| Topical oral corticosteroids, n (%) | 55 (19) | 39 (30) | 16 (10) | 0.000 |

| Immunomodulators, n (%) | 86 (30) | 70 (53) | 16 (10) | 0.000 |

| Biologics, n (%) | 51 (18) | 38 (29) | 13 (8) | 0.000 |

| Hospitalisation due to flare-up, n (%) | 22 (29) | 6 (8) | 16 (21) | 0.001 |

| Surgery, n (%) | 17 (6) | 14 (11) | 3 (2) | 0.006 |

Data are expressed as median, interquartile range (IQR), absolute and relative frequency. Mann–Whitney U test or Chi Square (Fisher) test.

CD: Crohn's disease; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; UC: ulcerative colitis.

In bold, statistically significant differences between UC and CD, p<0.05.

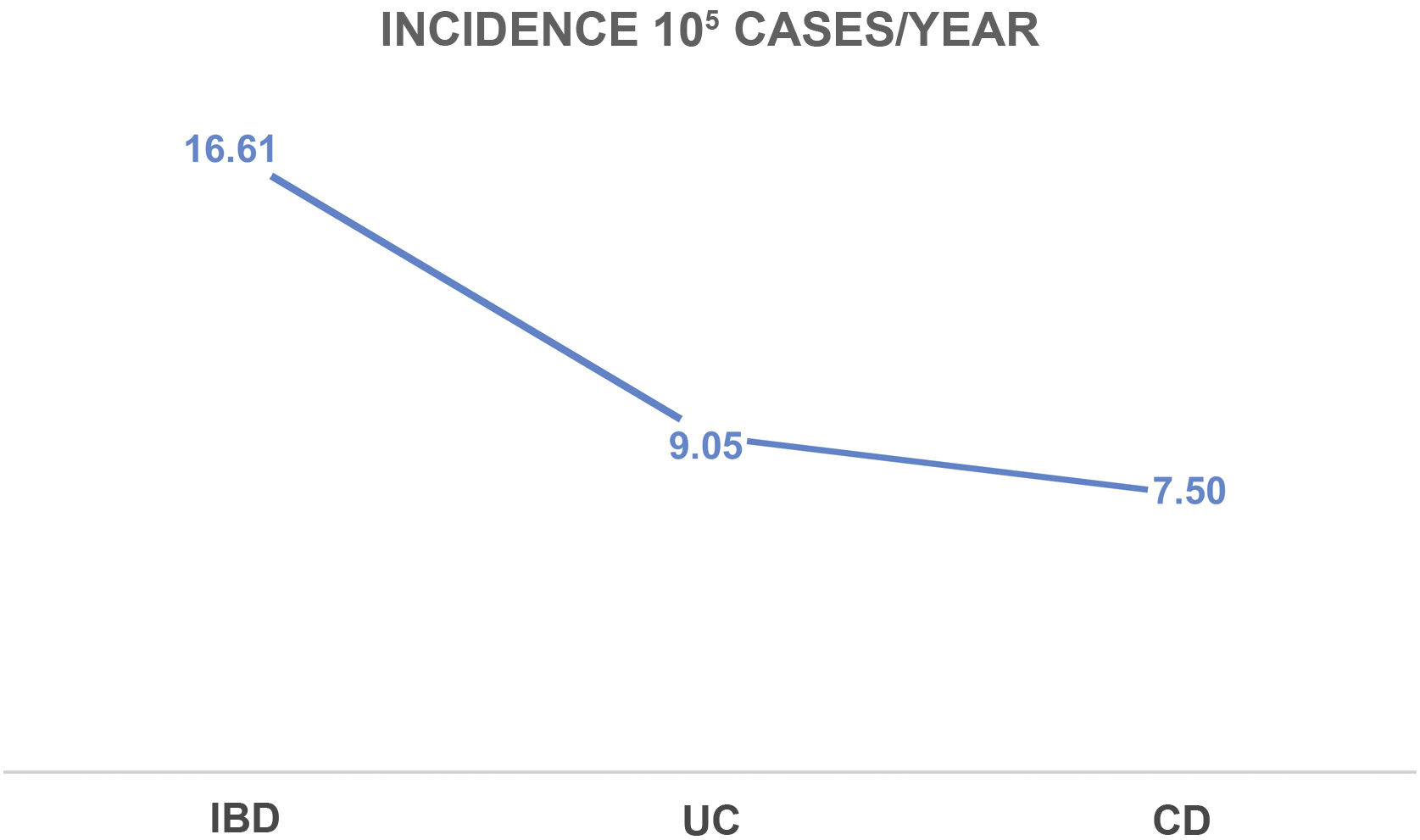

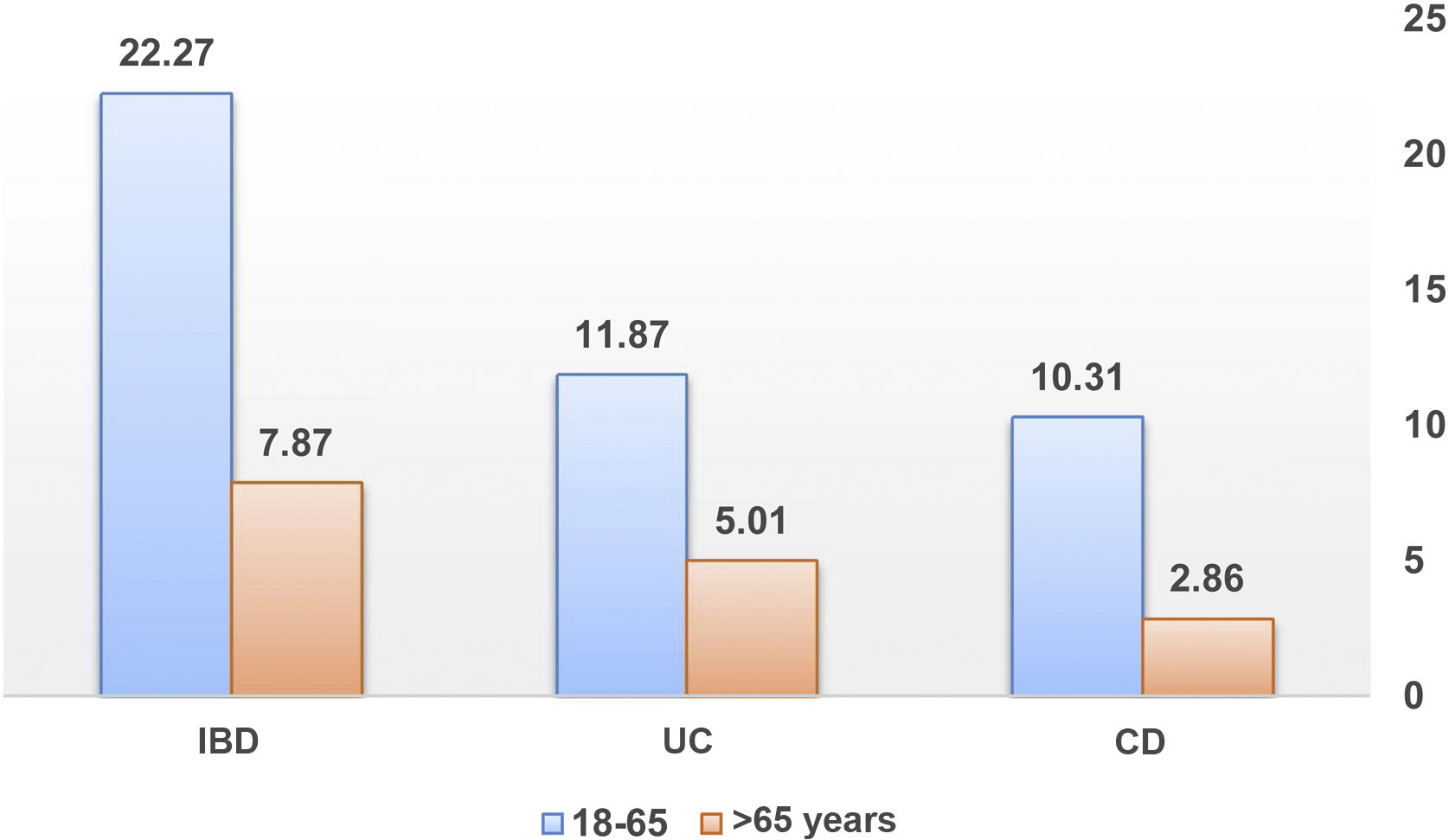

The IBD incidence rate in Castile and León in 2017 was 16.6 cases/100,000 inhabitants-year (9/105 cases of UC and 7.5/105 cases of CD), with a UC/CD ratio of 1.2:1. The incidence in patients older than 65 years was 7.9/105 (5/105 cases of UC and 2.9/105 cases of CD). These incidence rates are shown in Figs. 1–3.

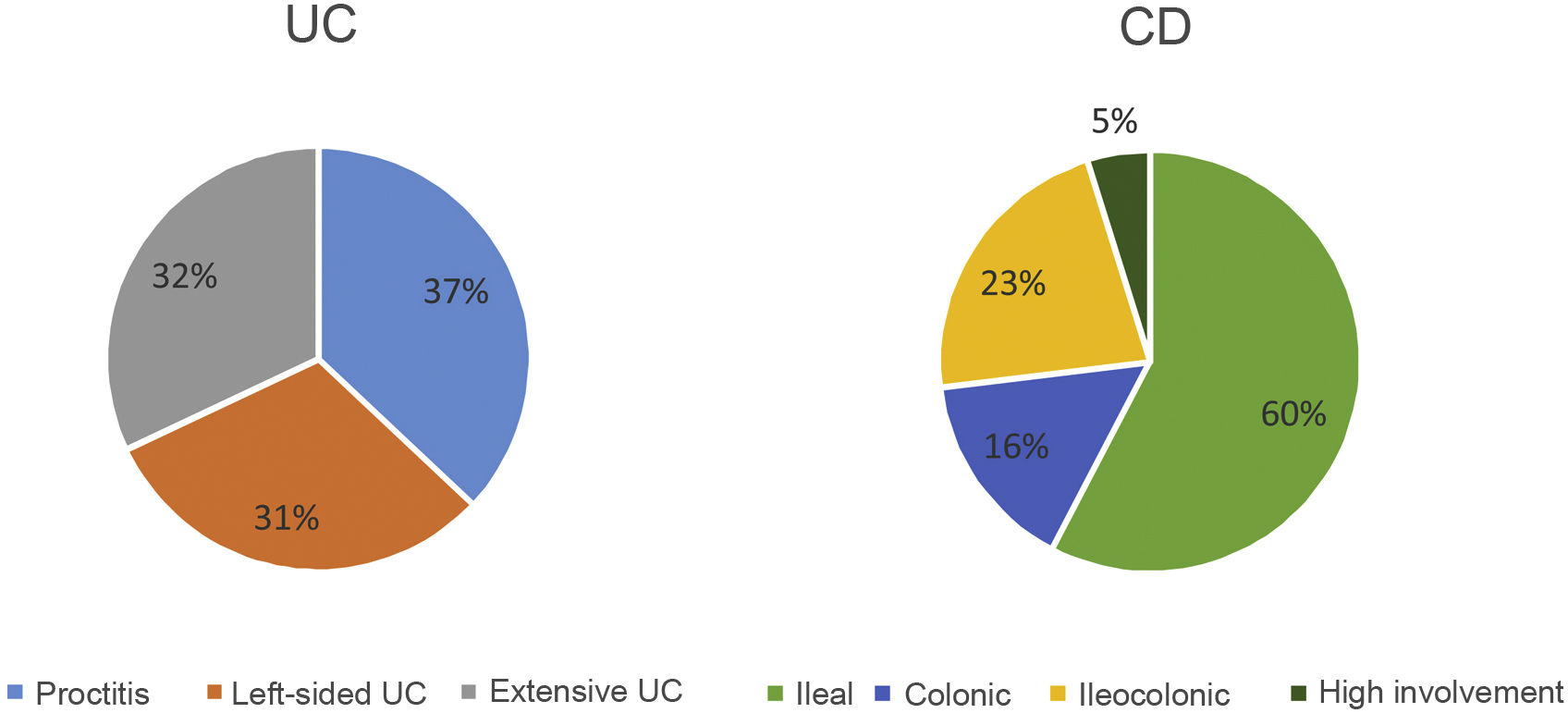

The extension at diagnosis (Fig. 4) in patients with UC was 37% proctitis (E1), 31% left-sided colitis (E2) and 32% extensive colitis (E3). In CD, 60% presented involvement in the terminal ileum (L1), 16% colonic involvement (L2) and 23% ileocolonic involvement (L3). Seven patients (5%) presented involvement of the upper digestive tract (L4) and 12 patients (9%) had concomitant perianal disease. The phenotype at diagnosis of CD was mostly inflammatory (B1) (84%), in 17 patients it was stenosing (B2) (13%) and in four patients it was fistulising (B3) (3%).

The median delay from symptom onset to diagnosis was two months (range 1−6 months). The family association was 14%.

Among active smokers (72 patients) more than 69% had CD, while among ex-smokers (98 patients) most (77%) were diagnosed with UC, these differences being statistically significant (p=0.000). At the time of diagnosis, 30 patients (10%) had extraintestinal manifestations, more frequent in CD.

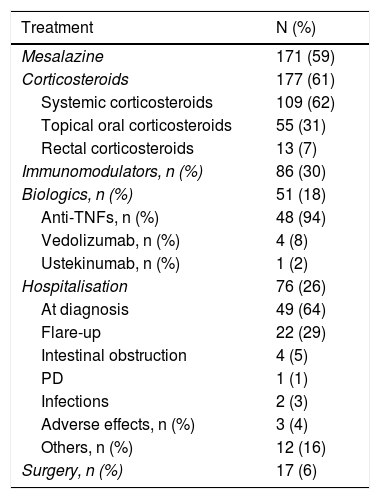

Regarding the medical treatment established during follow-up from the time of diagnosis (Table 2):

- -

One hundred and seventy-one patients (59%) received salicylates (oral and/or topical): almost all (96%) of the patients with UC and 14% of patients with CD.

- -

A total of 177 patients (61%) received corticosteroid therapy in its different forms (systemic, topical oral or rectal), 103 patients (58%) in the CD group and 74 patients (42%) in the UC group. Of the total number of patients treated with corticosteroids, 109 patients (62%) received them systemically (orally or intravenously), 55 patients (31%) received topical oral treatment and 13 (7%) topical rectal treatment. Significantly more CD patients (47%) received systemic corticosteroids, compared to 30% of UC patients (p=0.002). These differences were also significant when comparing the use of topical corticosteroids (30% vs. 10%; p=0.000) between patients with CD and those with UC. However, the use of rectal corticosteroids was significantly more frequent in patients with UC (7% vs. 2%; p=0.0026).

- -

Immunomodulatory therapy was used in a total of 86 patients (30%), being more frequently used in patients with CD (81%) than in patients with UC (19%); p=0.005.

- -

Regarding biologic treatment, significantly more patients with CD (29%) required biologic therapy compared to patients with UC (8%) (p=0.000), with anti-TNFs being the drugs mostly used (48 patients [17%]), while four patients received vedolizumab (1.4%) and one patient received ustekinumab (0.3%).

- -

Seventeen patients (6%) required surgery at diagnosis or during follow-up: nine patients (53%) in the abdominal region (resection of the small intestine and/or colon, total proctocolectomy with anastomosis or ileostomy), and eight patients (47%) in the perianal region (abscess drainage, seton and fistula treatment). The need for surgery was greater in patients with CD (11%) than in patients with UC (2%); p=0.000.

Medical and surgical treatment and hospitalisations.

| Treatment | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Mesalazine | 171 (59) |

| Corticosteroids | 177 (61) |

| Systemic corticosteroids | 109 (62) |

| Topical oral corticosteroids | 55 (31) |

| Rectal corticosteroids | 13 (7) |

| Immunomodulators, n (%) | 86 (30) |

| Biologics, n (%) | 51 (18) |

| Anti-TNFs, n (%) | 48 (94) |

| Vedolizumab, n (%) | 4 (8) |

| Ustekinumab, n (%) | 1 (2) |

| Hospitalisation | 76 (26) |

| At diagnosis | 49 (64) |

| Flare-up | 22 (29) |

| Intestinal obstruction | 4 (5) |

| PD | 1 (1) |

| Infections | 2 (3) |

| Adverse effects, n (%) | 3 (4) |

| Others, n (%) | 12 (16) |

| Surgery, n (%) | 17 (6) |

Data are expressed in absolute and relative frequency.

PD: perianal disease.

The overall hospitalisation rate was 26% (76 patients): 44 (58%) of the patients with CD and 32 patients (20%) with UC. The most common cause was admission at diagnosis (64%), followed by flare-up (29%), other causes (16%), obstruction (5%), adverse drug effects (4%), infections (3%) and perianal disease (1%). When analysing hospitalisation due to a clinical flare-up of the disease (22 patients), more UC patients (72%) were admitted than CD patients (27%); p=0.0001.

Table 1 shows the comparative study between the different variables of patients with CD and UC.

DiscussionIn recent decades, the incidence rates of IBD have been progressively increasing worldwide, in parallel with the industrial development of certain countries in Asia, Africa, South America and Eastern Europe, although prospective data are scarce and almost all come from retrospective data.6,7 In Shivananda's study of the north-south incidence in Europe for the years 1990–1993,16 a difference in incidence was reflected in favour of the countries of northern Europe, both for UC and CD, a difference that has currently been transferred to the east-west comparison, as reflected in the 2010 data from the European ECCO-EpiCom study.5 Compared to other European countries, Spain had similar rates, with an incidence of 9.4/105 for UC and 10.8/105 for CD,5 although it should be noted that only one Spanish centre from Galicia participated in this European study. Over time, new studies published in different parts of Spain (Oviedo, Madrid and Navarre) have shown this increase in the overall incidence of IBD in Spain, approaching the incidence described in northern European countries (5–12/105 for UC and 3.5–9.5/105 for CD).3,4,7 This study presents the first prospective data from an incident cohort of IBD in Castile and León with incidence rates similar to the highest reported in our country for patients with UC (9/105 cases), but lower for patients with CD (7.5/105 cases). This stability in the incidence of CD coincides with the rest of the Spanish regions that participated in the EPIDEM-IBD study.9

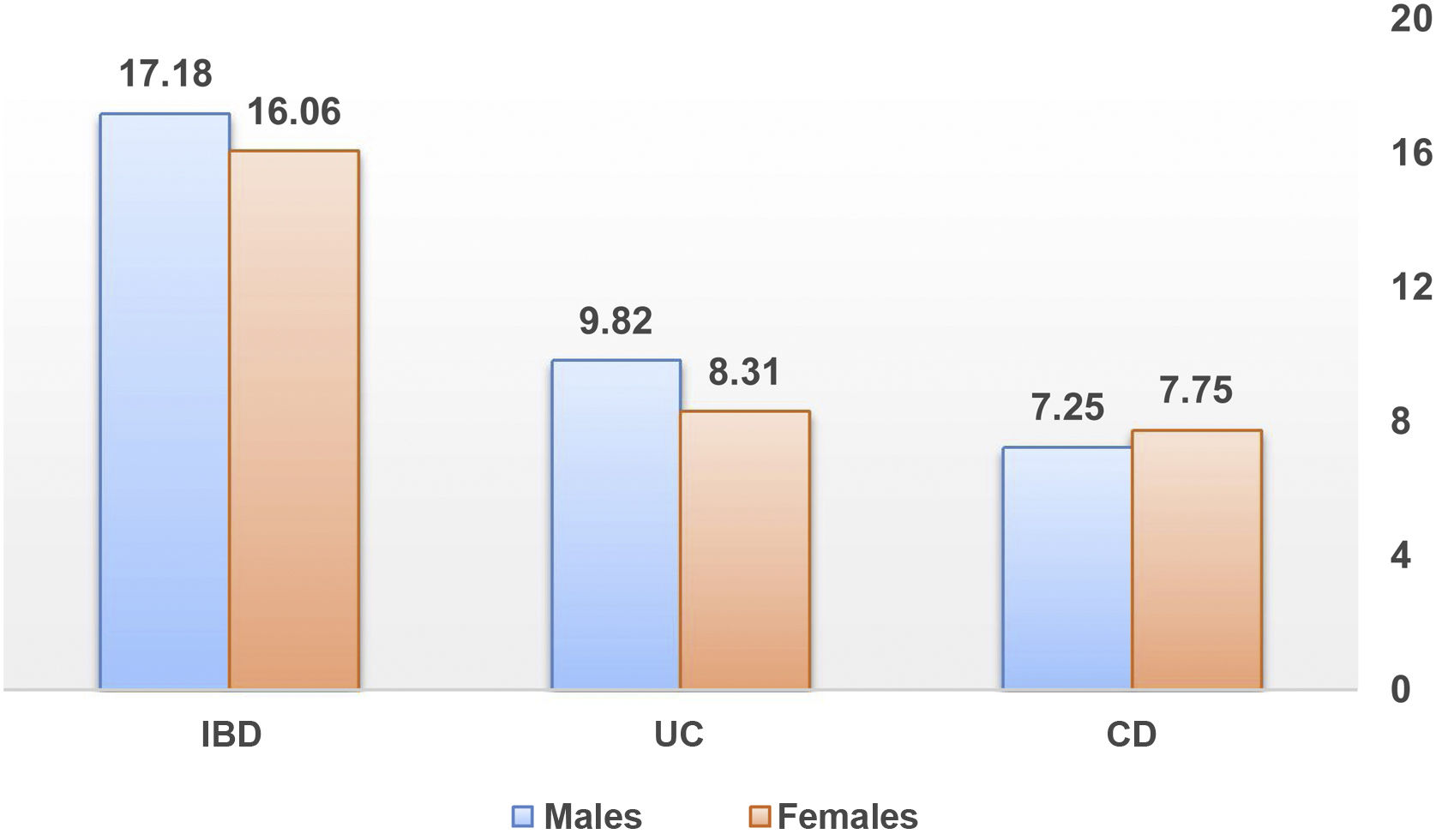

The female/male ratio for our IBD patients was 0.97, with a slight predominance of males in UC, but without statistical significance. The various published studies seem to agree that gender does not influence the incidence of IBD. Our data are within what has been described in the literature so far. However, a recent population study from the Asia-Pacific area shows that there is a predominance of the male sex in both IBD types at all ages.17

The clinical phenotypes and disease course of the subjects in our cohort were similar to those described in the latest prospective studies published, with a higher percentage of proctitis (37%) compared to the European series (20–21%),18,19 which probably reflects an exhaustive search for cases, due to our study design, which are often missed in tertiary hospitals. We also observed a lower percentage of high involvement (L4) in patients with CD (5%) compared to percentages of 10–15%, which is probably explained by the lack of early routine study of the upper tract in newly diagnosed patients with CD, and the short follow-up interval (one year). Although in the classic series20 the onset of patients with CD and an inflammatory pattern is approximately 80%, the Spanish data from the EpiCom study21 demonstrate a lower percentage (66–68%). Our data are closer to the classic series with a baseline percentage for the inflammatory pattern of 84%.

In our incident cohort, the use of salicylates was practically the norm in patients with UC, but we must point out that up to 15% of patients with CD were treated with salicylates, which confirms the resistance to change from a classic attitude in previous decades, since the evidence of the efficacy of salicylates in patients with CD is very low22 and their use in this scenario is currently not recommended by clinical guidelines.23

Regarding the natural history, globally the patients with CD in our incident cohort presented a worse clinical course than the patients with UC, evaluated by a greater consumption of corticosteroids, immunomodulators, biologics and surgery during the first year after diagnosis, with statistically significant differences, data that confirm what was published in previous European cohorts.18

The need for hospitalisation in IBD patients is common due to disease flare-ups. Specifically in patients with UC, a hospitalisation rate of 23% has been described in the Epi-IBD study at five years, being higher in western countries than in eastern ones.19 In the systematic review of population studies, published in 2018,24 the percentage of admissions in patients with UC was 17–29% per year. In our cohort, the percentage of admissions for patients with UC was 20%, and although the overall number of admissions was numerically higher in patients with CD (56%), it is noteworthy that admissions due to a disease flare-up were statistically more frequent in patients with UC (23%) than in patients with CD (8%) (p=0.001).

It has been described that the percentages of surgery in patients with UC and CD have remained stable during the last decades, with figures similar to those reported in our cohort during the first year (2% in UC and 11% in CD).

The greatest strength of our study is that it is a population-based and prospective study that included different tertiary and regional hospitals with exhaustive methodology, and it reflects the current incidence rates of patients with IBD in our community of Castile and León. A weakness, perhaps, is the short follow-up (nine months on average) of the patients, although the data from the national study will be published with a five-year follow-up, in which patients from our community are included. However, our results are consistent with those published in other countries with the same follow-up period.

ConclusionsThe incidence of patients with UC in our setting is increasing, while that of CD remains stable, with higher requirements in terms of the use of corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, biologics and surgery for patients with CD compared to patients with UC in the first year of follow-up, which indirectly translates into a worse natural history for these patients.

FundingFinancial support for the logistics and coordination of the research of the study at the national level through a FIS (Health Research Fund) grant from the Carlos III Institute (PI16/01296 and PFI17/00143), GETECCU (Spanish Working Group on Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis) and MSD, without having any role in the design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript or in the decision to publish it.

Conflicts of interestDr R. Sáiz: support for training activities for Jannsen, Ferring and Gilead.

Dr J Barrio: has served in speaking or consulting roles and has received research or educational funding from MSD, AbbVie, Takeda, Janssen and Ferring.

Dr L. Fernández-Salazar: support for research and/or training activities for Tillots Pharma, Janssen and Takeda.

Dr L. Arias: scientific advice, support for research and/or training activities for AbbVie, FAES Pharma, Kern Pharma, Ferring and MSD.

Dr M. Sierra Ausín: has received fees for training activities, research support and advisory services for Takeda, Janssen, MSD, AbbVie, Pfizer, Ferring and Falk.

Dr C. Piñero: scientific advice, support for research and/or training activities for AbbVie, FAES Pharma, Janssen, Ferring, Pfizer and Takeda.

Dr A. Fuentes Coronel: support for research and/or training activities for AbbVie, Ferring, MSD, Falk, Tillots Pharma, Janssen, Pfizer and Takeda.

Dr L. Mata: scientific advice, support for research and/or training activities for Janssen, AbbVie, Faes and Takeda.

Dr M. Vásquez: no conflict of interest.

Dr A. Carbajo: support for training activities for Jannsen and AbbVie.

Dr N. Alcaide: no conflict of interest.

RN N. Cano: scientific advice, support for research and/or training activities for Janssen, Sandoz, Takeda, AbbVie and MSD.

Dr A. Nuñez: support for training activities for Jannsen and AbbVie.

Dr P. Fradejas: scientific advice, support for research and/or training activities for AbbVie, FAES, Falk, Ferring, Kern Pharma, MSD, Pfizer Pharma and Takeda.

Dr M. Ibáñez: scientific advice, support for research and/or training activities for Janssen, AbbVie, Faes and Takeda.

Dr L. Hernández: no conflicts of interest.

Dr B. Sicilia: scientific advice, support for research and/or training activities for Tillots Pharma, Kern Pharma, AbbVie, Janssen, Pfizer and Takeda.