Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is associated with an increased risk of developing dysplasia and cancer. This is mainly due to the chronic inflammation, which is an independent risk factor linked to the duration and extent of the disease.1

The risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) in IBD has decreased in recent years, probably due to the optimisation of medical treatment and endoscopic surveillance. However, despite these advances, there is a lack of consensus on the optimal strategies for surveillance and the decision to resort to surgical intervention.2

We present the case of a patient with a diagnosis of CRC and long-standing ulcerative colitis (UC). Genetic testing confirmed he was a carrier of the familial BRCA1 pathogenic mutation, raising the possibility of a genetic link between the two diseases.

This was a 35-year-old male with a 15-year history of pan-ulcerative colitis on treatment with mesalazine. Onset had been at age 20 with a mild-to-moderate flare-up. He was initially treated with azathioprine, but it was discontinued after three months due to gastrointestinal intolerance. Since then he has been on monotherapy with mesalazine and remained in clinical remission at check-ups.

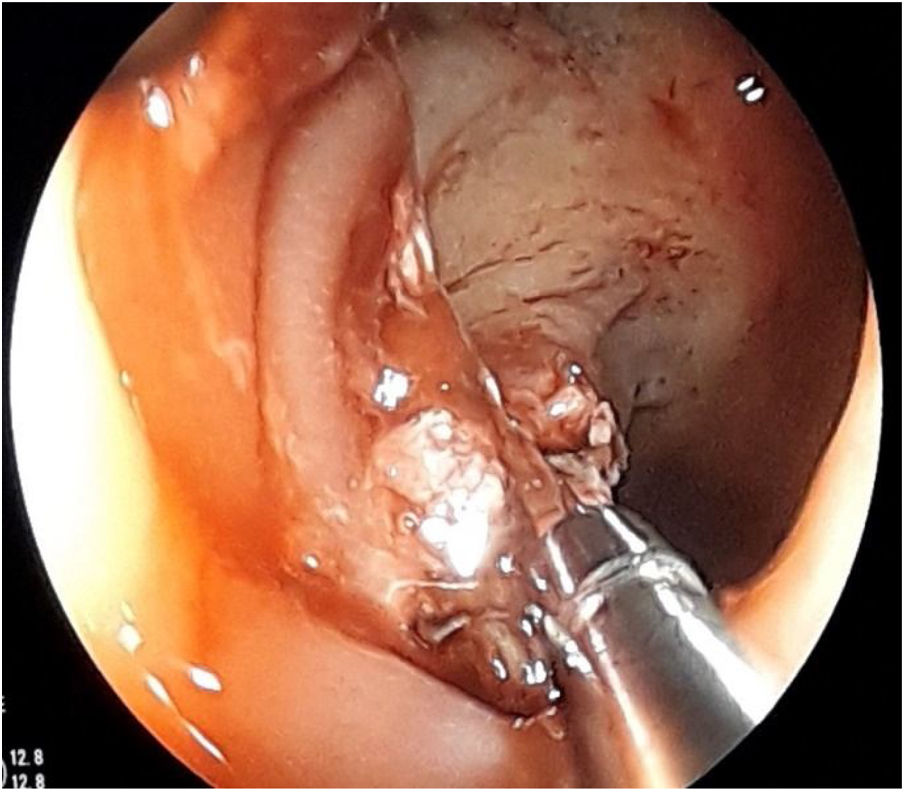

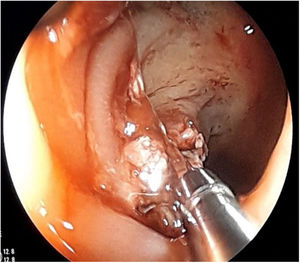

The first endoscopy for CRC surveillance ten years after diagnosis detected a flat polyp (0-IIa) of about 2cm in the transverse colon which was biopsied and tattooed, as it exhibited the non-lifting sign (Fig. 1). He was referred to surgery and had a total proctocolectomy, with examination of the surgical specimen confirming ulcerative-invasive adenocarcinoma.

As the patient had a family history of breast cancer diagnosed at a young age (mother died at age 40, sister diagnosed at 35 and carrier of the BRCA mutation), he was referred to the Genetic Counselling Unit, where he was diagnosed as having a mutation in BRCA1, with particular susceptibility to breast and prostate cancer and, in his case, to CRC due to his history of IBD.

Inflammatory bowel disease develops in patients who are genetically predisposed and then exposed to environmental factors, which are not fully understood. These patients have an increased risk of CRC, attributable to the carcinogenic effect of chronic mucosal inflammation.

The risk of colorectal cancer for any patient with ulcerative colitis is high, estimated at 2% after 10 years of disease, 8% after 20 years and 18% after 30 years.3

There are reports in the literature of various different genetic factors being involved in the development and severity of IBD. However, the potential for simultaneous predisposition to UC and CRC has not been studied from a genetic point of view.

Alterations in the expression of the E-cadherin gene (CDH1), DNA methylation (mainly its promoters p14 and p16) and microRNA can act as oncogenes and favour the development of CRC in this type of patient.4

BRCA 1/2 mutations are associated with an increased risk of breast, ovarian, pancreatic and prostate cancer. However, no association with colorectal cancer has been demonstrated to date.

In the case of our patient, there was a double risk factor for developing CRC: long-standing extensive UC or pan-UC, and being a carrier of the familial BRCA1 pathogenic mutation.

Early detection of these genetic alterations could be useful, as we could use them as molecular biomarkers for risk in order to predict dysplasia and cancer.5

Although this is a case report, in view of the lack of cases published in the world medical literature associating the BRCA mutation with CRC and IBD, this finding highlights the importance of genetic testing in the clinical management of both CRC and IBD.

It is particularly relevant in young patients with IBD and a family history of CRC. Routine genetic testing should be considered in such patients, as it could modify the clinical management and the choice of optimal strategy when detecting low-grade dysplasia, which is still very much the subject of debate.

Please cite this article as: Moreno Moraleda I, Lázaro Sáez M, Diéguez Castillo C, Hernández Martínez Á. Enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal y cáncer colorrectal hereditario: ¿existe un vínculo genético? Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;44:133–134.