In recent years there have been advances in the management of non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding that have helped reduce rebleeding and mortality. This document positioning of the Catalan Society of Digestologia is an update of evidence-based recommendations on management of gastrointestinal bleeding peptic ulcer.

En los últimos años se han producido avances en el manejo de la hemorragia digestiva alta no varicosa que han permitido disminuir la recidiva hemorrágica y la mortalidad. El presente documento de posicionamiento de la Societat Catalana de Digestologia es una actualización de las recomendaciones basadas en la evidencia sobre el manejo de la hemorragia digestiva por úlcera péptica.

In terms of gastrointestinal diseases, non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB), and particularly peptic ulcer bleeding, is one of the most common causes of hospitalisation and represents a significant economic and healthcare burden. Significant advances in the management of this gastroenterological condition have been made in recent years that have reduced rebleeding and mortality.1,2

This position paper is an update of the evidence-based recommendations on the management of gastrointestinal bleeding due to peptic ulcer. The Catalan Society of Gastroenterology invited the authors listed to contribute to the drafting and subsequent review of the UGIB management position paper. Two gastroenterologists (RCF and PGI) acted as coordinators. The authors included gastroenterologists/endoscopists/emergency physicians and surgeons. They drafted key questions/recommendations that were reviewed and approved by the participants. The coordinating team comprised four sub-working groups (initial measures, endoscopic treatment, hospital care and follow-up after discharge), each with its own coordinator. The key questions/recommendations were divided between these four sub-working groups for drafting. The recommendations are presented in chronological order, consistent with their application in clinical practice. They include the quality of evidence (QE) (high, moderate, low or very low) and the strength of recommendation (SR) (strong or weak), in accordance with the GRADE approach (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation).3 Finally, the manuscript was reviewed and accepted by all the authors and published on the Catalan Society of Gastroenterology's website as a Position Paper (Document de Posicionament).

Initial measuresMost patient deaths are not bleeding-related. Cardiopulmonary decompensation accounts for 37% of all non-bleeding-related causes of mortality.4,5 As such, prompt and appropriate initial resuscitation should precede any diagnostic measure (SR: strong; QE: moderate).

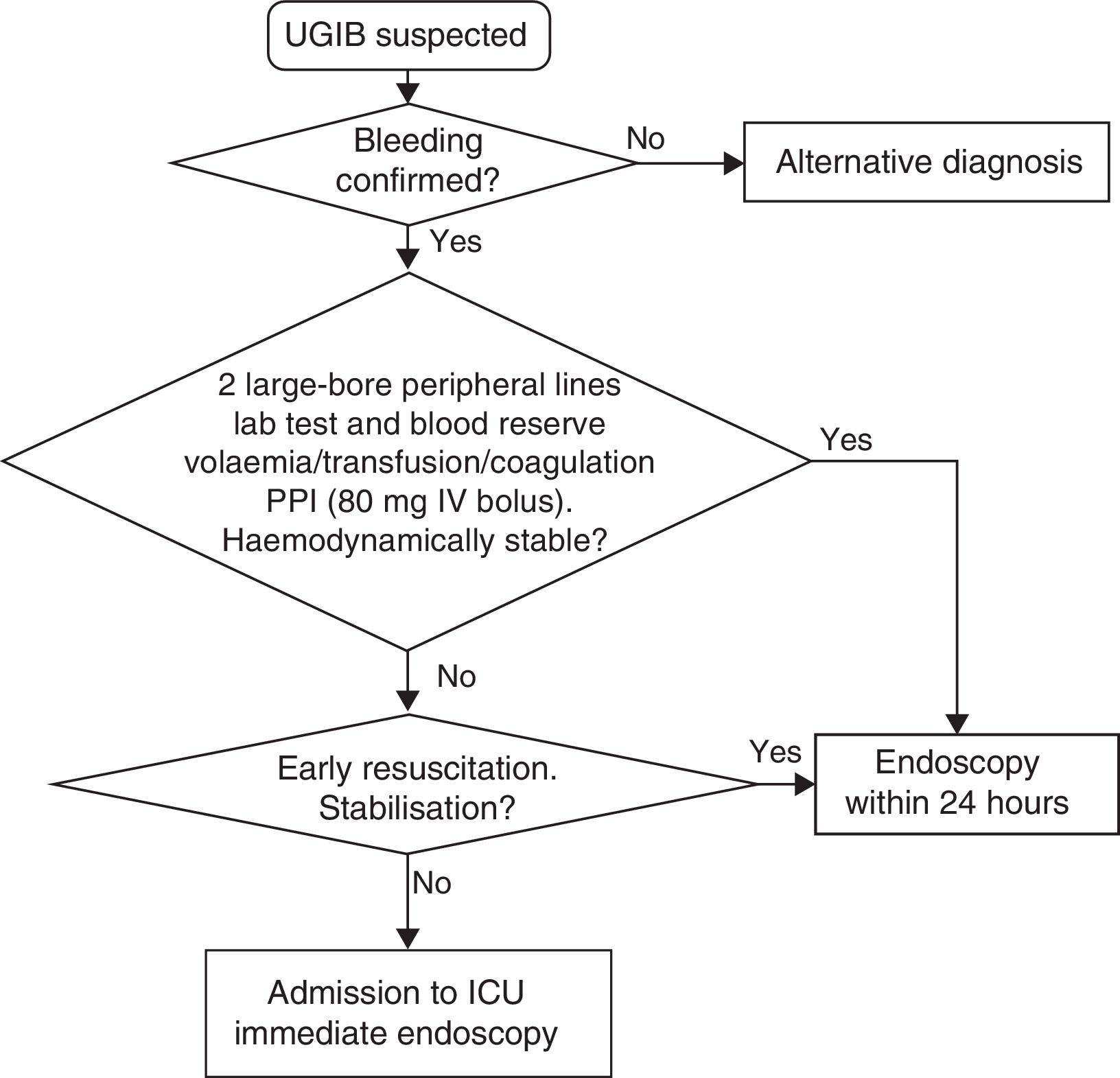

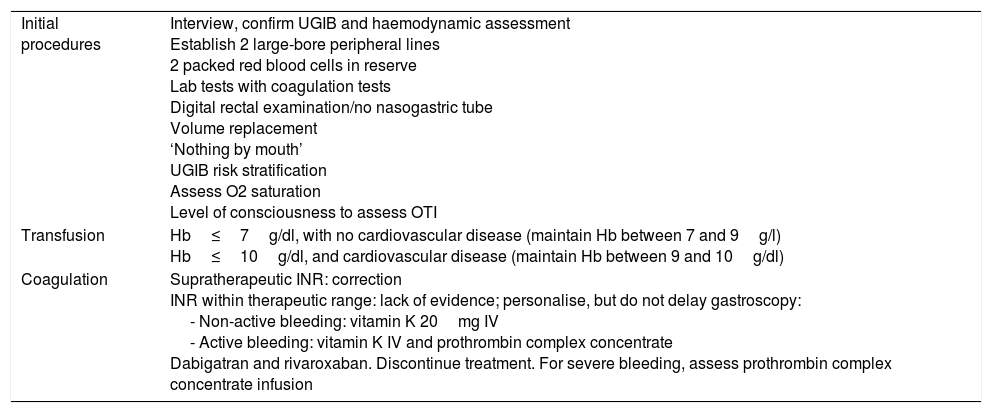

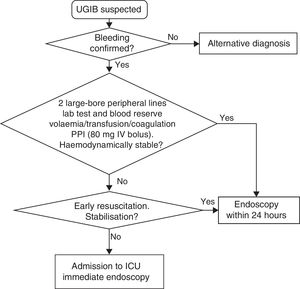

The measures to be taken immediately after admission are summarised in Table 1 and Fig. 1.

Initial measures in UGIB.

| Initial procedures | Interview, confirm UGIB and haemodynamic assessment Establish 2 large-bore peripheral lines 2 packed red blood cells in reserve Lab tests with coagulation tests Digital rectal examination/no nasogastric tube Volume replacement ‘Nothing by mouth’ UGIB risk stratification Assess O2 saturation Level of consciousness to assess OTI |

| Transfusion | Hb≤7g/dl, with no cardiovascular disease (maintain Hb between 7 and 9g/l) Hb≤10g/dl, and cardiovascular disease (maintain Hb between 9 and 10g/dl) |

| Coagulation | Supratherapeutic INR: correction INR within therapeutic range: lack of evidence; personalise, but do not delay gastroscopy: - Non-active bleeding: vitamin K 20mg IV - Active bleeding: vitamin K IV and prothrombin complex concentrate Dabigatran and rivaroxaban. Discontinue treatment. For severe bleeding, assess prothrombin complex concentrate infusion |

The initial interview should include assessment of the following:

- a.

Type of bleeding: “Coffee-ground vomitus” or haematemesis, with or without melaena.

- b.

Haemodynamic impact and severity: massive haematemesis, sweating, loss of consciousness (syncope or lipothymia).

- c.

Comorbidity: taking into account the patient's prior history or any clinical data suggestive of liver disease (patients with gastrointestinal bleeding from oesophageal or gastric varices require a different approach) and any history of cardiovascular disease.

- d.

Ask about the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants, including direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs): dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban and edoxaban.

The baseline physical examination should include the following:

- a.

Confirm the bleeding:

- 1.

Digital rectal examination (if in doubt).

- 2.

Nasogastric tubes rarely change the approach and are very uncomfortable for patients. Their use should be extremely restricted. Nasogastric intubation in patients with suspected UGIB is not a predictive factor for endoscopic therapy, has no impact on patient outcome, does not change clinical attitudes and may lead to complications.6 For all these reasons, nasogastric tubes should not be used routinely even though a very select group of patients could benefit from their placement. Should it be decided to place a nasogastric tube, the result obtained from the aspirate must be recorded in the patient's medical record as a quality indicator in the management of patients with UGIB (SR: strong; QE: moderate). The tube should be withdrawn after evaluating the appearance of the gastric aspirate. Cold saline lavage is not recommended and there is no clear evidence that nasogastric tube lavage improves the diagnostic or therapeutic performance of the endoscopy 7–9(SR: strong; QE: low).

- 1.

- b.

Assess the haemodynamic status: systolic blood pressure and heart rate, as well as signs of peripheral hypoperfusion. Bleeding severity is established from these data. Oxygen saturation and level of consciousness are also useful in the baseline assessment of patients with UGIB.

- c.

Rule out liver cirrhosis (evaluate clinical signs of chronic liver disease and the presence of encephalopathy and/or ascites).

After this baseline assessment, and once haemodynamic stabilisation has begun, it is recommended to complete the interview and the physical examination.

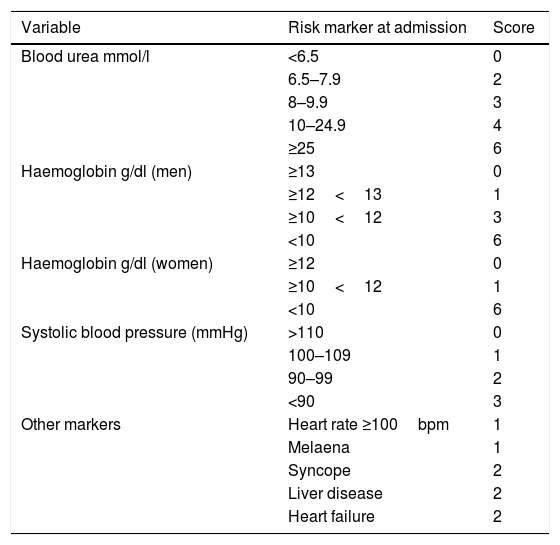

The use of validated classification systems is recommended to split the patients into high and low risk groups. Risk stratification may support such decisions as when to perform the endoscopy and when to discharge the patient (SR: strong; QE: moderate). In this regard, the Glasgow-Blatchford bleeding score is recommended for pre-endoscopic risk stratification (Table 2). Patients with a very low risk (score 0: systolic blood pressure ≥110mmHg, heart rate <100bpm, Hb 13g/dl in men or 12g/dl in women, BUN <6.5mmol/l and lack of melaena, no syncope, liver disease or heart failure) do not require emergency endoscopy or hospitalisation10 (SR: strong; QE: moderate).

Glasgow-Blatchford bleeding score.

| Variable | Risk marker at admission | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Blood urea mmol/l | <6.5 | 0 |

| 6.5–7.9 | 2 | |

| 8–9.9 | 3 | |

| 10–24.9 | 4 | |

| ≥25 | 6 | |

| Haemoglobin g/dl (men) | ≥13 | 0 |

| ≥12<13 | 1 | |

| ≥10<12 | 3 | |

| <10 | 6 | |

| Haemoglobin g/dl (women) | ≥12 | 0 |

| ≥10<12 | 1 | |

| <10 | 6 | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | >110 | 0 |

| 100–109 | 1 | |

| 90–99 | 2 | |

| <90 | 3 | |

| Other markers | Heart rate ≥100bpm | 1 |

| Melaena | 1 | |

| Syncope | 2 | |

| Liver disease | 2 | |

| Heart failure | 2 |

Depending on the study, the cut-off point for low-risk patients was between 0 and 3 points.

The early correction of hypotension is the most effective initial measure to significantly reduce UGIB-associated mortality (SR: strong; QE: moderate).5

Initial management and haemodynamic stabilisation- 1.

Establish two large-bore peripheral lines for the rapid infusion of crystalloids (volume replacement) or blood products if necessary. 16G or 18G venous catheters have a peak infusion flow rate of 220ml/min and 105ml/min, respectively. This flow rate is much higher than the sum of the peak flow rate of the three lumen of a central venous catheter, some 70ml/min.11,12

- 2.

Conduct lab tests (complete blood count, coagulation tests, liver function and renal function tests with ionogram). Increased urea with normal creatinine levels is suggestive of UGIB, although it is only moderately reliable.13,14

- 3.

Store blood in reserve (at least two packed red blood cells).

- 4.

Replace volume with crystalloids. There is no evidence that colloids are better than normal saline solution (SR: strong; QE: high).15

- 5.

Specify ‘nothing by mouth’ should an endoscopy be required.

In patients with signs of severe bleeding and shock despite initial volume replacement, haematocrit levels do not reflect the degree of blood loss. In these cases, the joint administration of packed red blood cells and crystalloids is recommended. The transfusion criteria should be liberal until the patient has been stabilised.

In stable patients with no cardiovascular disease or active bleeding and haemoglobin ≤7g/dl, restrictive transfusion is recommended to maintain haemoglobin levels between 7 and 9g/dl (SR: strong; QE: moderate). However, in young, haemodynamically stable patients with no underlying disease and no signs of active bleeding, watchful waiting may be adopted with haemoglobin levels below 7g/dl, if the anaemia is well tolerated.16

In patients with cardiovascular disease and/or active bleeding, transfusion is recommended to maintain haemoglobin levels at least between 9 and 10g/dl (SR: strong; QE: low).

Correction of coagulation disordersIt is recommended to correct coagulation disorders in patients treated with anticoagulants and acute bleeding (SR: strong; QE: low).

- -

Coumarin derivatives:

In patients with supratherapeutic INR levels, it is recommended to correct coagulation to therapeutic levels, including before diagnostic and therapeutic procedures such as endoscopy. In the event of active bleeding and haemodynamic instability, coagulation must be corrected as a matter of urgency by administering vitamin K and prothrombin complex concentrate.17,18 Fresh frozen plasma could be administered as a second option (10ml/kg). For non-active bleeding, intravenous vitamin K can be administered (20mg, single dose). If the clinical situation allows, it is recommended to improve the INR to <2.5 before conducting the endoscopy with or without haemostatic therapy (SR: weak; QE: moderate).19

In patients with an INR within therapeutic range, there is no evidence one the benefit of correcting anticoagulation. Although very few studies have been conducted and only on small samples, no differences in the rebleeding, surgery or mortality rates of these patients have been shown when correction of anticoagulation is compared to maintaining anticoagulation within therapeutic range. In these cases, the risks and benefits of discontinuing anticoagulant therapy must be assessed for each individual patient. In any case, an INR within therapeutic range should not delay the endoscopy.20,21

The risks and benefits of maintaining anticoagulation must be weighed up in all patients. As a general rule, it is recommended to reverse anticoagulation with coumarin derivatives in patients with moderate to severe bleeding.

- -

DOAC:

It is recommended to temporarily suspend DOACs in patients with suspected acute bleeding in collaboration with the haematologist and/or cardiologist (SR: strong; QE: low). The use of prothrombin complex concentrates may be considered. The efficacy of these blood products to reverse anticoagulant effects is supported by both experimental and clinical data.

Dabigatran is eliminated by the kidneys, which means that it is important to maintain appropriate diuresis. In cases of severe uncontrolled bleeding, especially in patients with kidney failure, haemodialysis could be effective. Furthermore, dabigatran is the only anticoagulant with a specific marketed antidote: idarucizumab.22–24

Their use before endoscopy should not be systematically indicated. Intravenous erythromycin (single dose, 250mg administered 30–120min prior to the endoscopy) could be useful in a select group of patients (with suspected accumulation of blood and/or clots in the stomach) to improve the diagnostic efficacy of the emergency endoscope. Erythromycin significantly improves visibility during the endoscopy and reduces the need for a second examination, the number of blood units transfused and length of hospital stay (SR: strong; QE: high).25,26 It may also be administered before repeating the endoscopy to patients in whom the accumulation of blood in the stomach prevents appropriate visibility of the gastric mucosa (SR: strong; QE: moderate).

Intravenous proton pump inhibitors (PPI)Administering intravenous PPI prior to endoscopy reduces active bleeding and high-risk clinical signs, the need for endoscopic therapy and mean length of hospital stay (SR: strong; QE: moderate), but it has not been shown to reduce rebleeding, the need for surgery or mortality.27

Its administration should not delay the endoscopy (SR: strong; QE: moderate).

It is particularly important to administer intravenous PPI if the endoscopy is not expected to be conducted immediately. The starting dose is not well established due to a lack of randomised studies. The recommended dose is an 80mg bolus of intravenous PPI, followed by an 8mg/h infusion dissolved in normal saline (in a dextrose solution). The infusion should be changed every 12h due to the molecule's instability in solution. The only randomised study used esomeprazole. Although it is likely that all PPIs are equivalent, it is unknown whether other PPI will be equally effective.27,28

Other drugsUse of tranexamic acid, somatostatin or its analogue octreotide in patients with UGIB is not recommended (SR: strong; QE: low).29,30

EndoscopySpecific UGIB management protocols should include access to an emergency endoscopy, an endoscopist trained in performing endoscopic haemostatic techniques and a nurse trained in performing emergency endoscopy (SR: strong; QE: low).

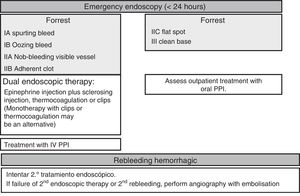

Endoscopy prioritisationEarly endoscopy (within the first 24h of admission) is recommended as it enables the risk of rebleeding to be stratified and facilitates the early discharge of low-risk patients. It also enables endoscopic treatment to be conducted early in high-risk patients (SR: strong; QE: moderate).1,31

The analysis of subgroups in largely observational studies suggests that very early endoscopy within the first 12h in very high-risk patients reduces hospital stay (SR: strong; QE: low).32–35

Very high-risk patients (with persistent haemodynamic instability) may also benefit from endoscopy within the first 6h so as to administer endoscopic haemostatic therapy even earlier. However, no studies have been conducted that confirm this assumption (SR: strong; QE: very low).

It is recommended to assess the risks and benefits of endoscopy on an individual patient basis, particularly patients at risk of complications. This includes subjects with acute coronary syndrome, perforation or persistent haemodynamic instability (SR: strong; QE: low).

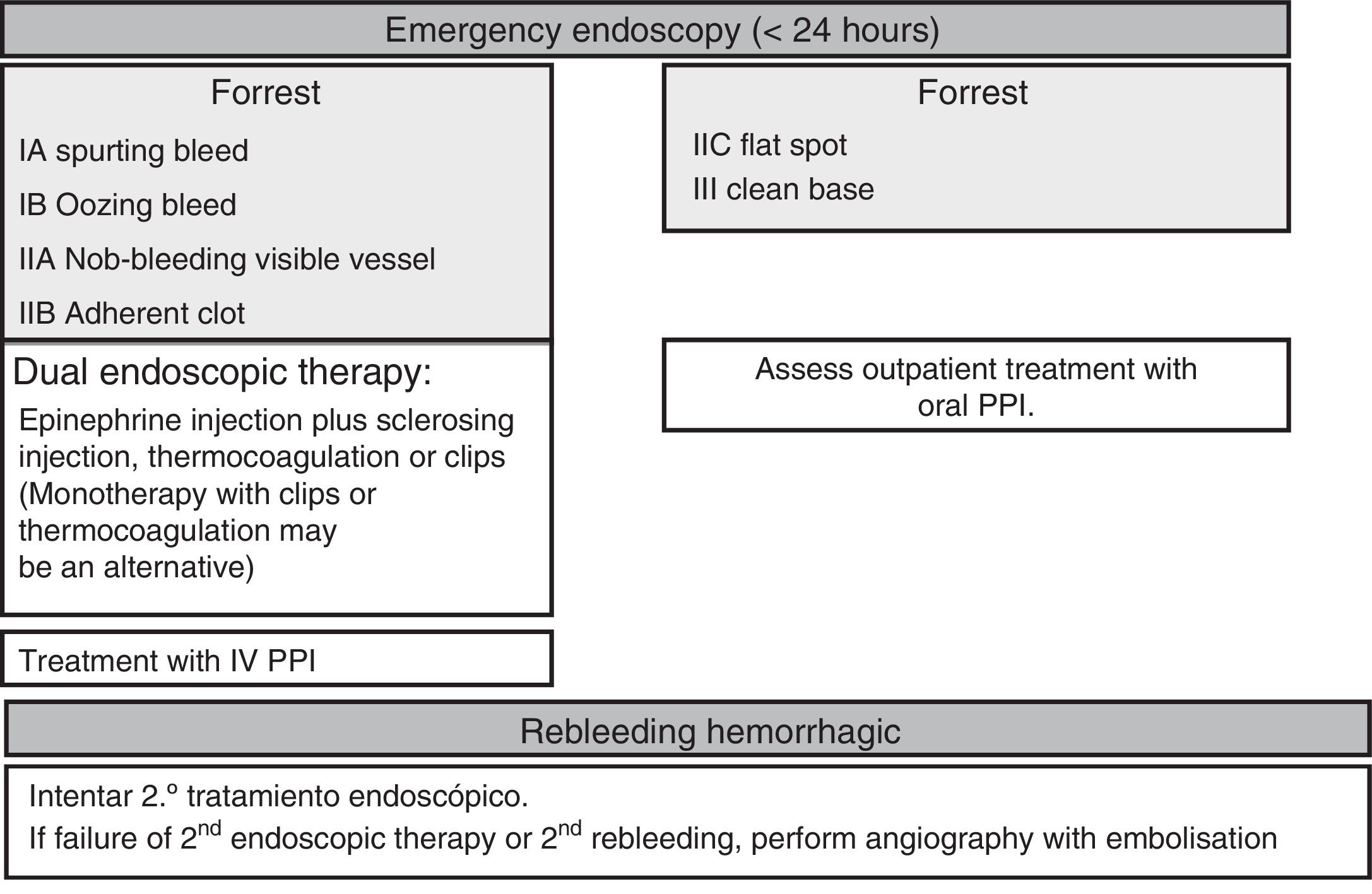

Endoscopic therapyThe endoscopy should identify the presence and type of stigmata of recent bleeding as they have a predictive value for the risk of persistent bleeding or rebleeding and determine whether or not endoscopic haemostatic therapy is indicated. Endoscopic therapy is not indicated in patients with low-risk stigmata (ulcers with a flat spot or a clean base) given the good prognosis of these lesions with less than a 5% chance of rebleeding (SR: strong; QE: high).36 Irrigation should be performed to dislodge any adherent clot found attached to an ulcer, and the underlying lesion may require endoscopic therapy. If the clot fails to dislodge, endoscopic therapy applied to the base of the clot is safe and may reduce the rate of rebleeding, particularly in patients at a higher risk of bleeding (the elderly, presence of comorbidities, etc.). However, there is no evidence to suggest that this treatment is better than high-dose PPI (SR: strong; QE: high).37

Endoscopic therapy is indicated in patients with active bleeding (spurting or oozing) or with a non-bleeding visible vessel (SR: strong; QE: high).38 The aim of endoscopic therapy is to achieve permanent haemostasis; in other words, to control the initial bleeding and prevent rebleeding.

Controlled studies have shown that endoscopic therapy with thermocoagulation or injections effectively meets this objective and significantly reduces the need for emergency surgery while improving patient survival (SR: strong; QE: high).39

In terms of endoscopic therapy, there is currently robust evidence to suggest that despite being effective in achieving initial haemostasis, monotherapy with epinephrine injection does not yield optimal results as it is associated with higher rates of rebleeding than dual therapy (SR: strong; QE: high). Epinephrine injection should be administered with a second endoscopic haemostatic therapy, such as endoscopic clips, thermocoagulation (with bipolar electrocoagulation or “heater probe”) or sclerosing injection (absolute alcohol, polidocanol or ethanolamine), thrombin injection or tissue adhesive injection.40,41 Endoscopic clips and thermocoagulation may also be used in monotherapy as combination therapy has not been shown to be clearly superior to monotherapy in comparative studies (SR: weak; QR: moderate).42 However, the statistical power of these studies is questionable.

As such, epinephrine pre-injection may be useful in clinical practice, particularly in the event of active bleeding, as this facilitates initial haemostasis and the application of a more satisfactory definitive treatment using thermocoagulation or clips. In comparative studies, clips have been shown to be as effective as thermocoagulation or sclerosing injection, although with varied outcomes. New types of clip are currently available that offer technical advantages over their predecessors, such as their size, the ability to guide their placement and greater adherence strength and stability once they have been released. Nevertheless, studies that evaluate their benefit in clinical practice have yet to be conducted. The advantage of clips over thermocoagulation or injection is that they do not cause tissue damage, making them potentially indicated for anticoagulated patients or patients on antiplatelet therapy, although this indication has not been properly evaluated (SR: weak; QE: very low). Laser, argon gas, monopolar electrocoagulation or thrombin or tissue adhesive injections are not recommended in first-line endoscopic therapy as they have not been shown to be more effective than other methods and are associated with a potential risk of severe complications.38 Having said that, bipolar electrocoagulation, the “heater probe” and sclerosing injection are not without their risks. Although Hemospray® could be used as salvage therapy in specific scenarios (e.g. hidden ulcers or lesions with diffuse bleeding), it cannot be recommended owing to the lack of controlled studies.43,44

Second-lookThe systematic conduct of a second-look endoscopy is not recommended because its benefit in clinical practice has not been proven in controlled studies (SR: strong; QE: high). Nevertheless, these same studies also suggest that it could be useful in certain very high-risk patients, but suitable studies with prognostic scores to identify these patients with an appropriate degree of sensitivity and specificity should be conducted (SR: weak; QE: low). Furthermore, studies to assess the feasibility of a second-look endoscopy are outdated and do not include the appropriate antisecretory therapy or, in many cases, optimal haemostatic therapy strategies.45–47 In this regard, a recent randomised study48 found that after endoscopic therapy, the infusion of high-dose PPI is not inferior to second-look endoscopy with an IV bolus of PPI in the prevention of rebleeding. Nevertheless, a study conducted on the Asian population with the random choice of non-inferiority margin and without showing whether or not the increased intragastric pH was sufficient.

Hospital carePrognostic scores and acting in accordance with the prognosisPost-endoscopy prognostic scores are recommended in order to split patients into different groups according to their rebleeding and mortality risk, and to thereby optimise the clinical approach (SR: weak; QE: moderate).49 Furthermore, the use of clinical trajectories could optimise the multidisciplinary management and protocols of patients with UGIB and reduce the length of hospital stay.

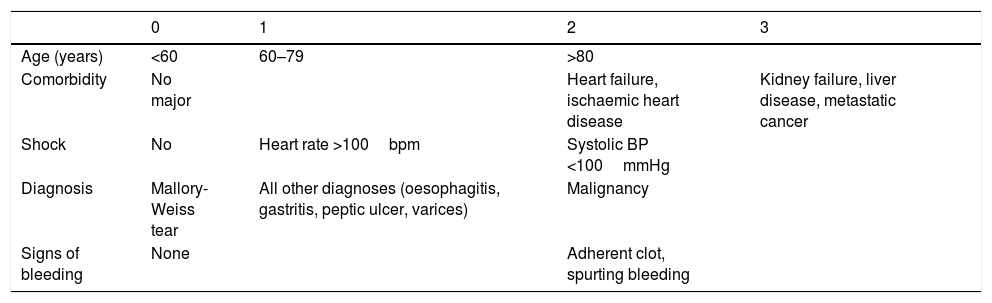

The Rockall score50 (Table 3) is the most well-known prognostic score and has been validated in numerous studies. It can identify patients with the lowest risk of rebleeding and mortality who could benefit from outpatient care. It can also identify high-risk patients who require appropriate care to minimise morbidity and mortality. Low-risk patients with limited or no comorbidity could begin their diet and be discharged after the endoscopy (SR: strong; QE high). Clinical judgement may be used based on the following parameters: haemodynamic stability, lack of comorbidities, ulcers with a flat spot or a clean base and appropriate family support at the patient's home. Patients at high risk of rebleeding and mortality, both according to clinical criteria (elderly, hypovolaemic shock and severe comorbidity) and endoscopic criteria (Forrest Ia-IIb) should be hospitalised for at least 72h and should fast for the first 24–48h in the event that a second endoscopy or surgery may be necessary.

Rockall score.

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | <60 | 60–79 | >80 | |

| Comorbidity | No major | Heart failure, ischaemic heart disease | Kidney failure, liver disease, metastatic cancer | |

| Shock | No | Heart rate >100bpm | Systolic BP <100mmHg | |

| Diagnosis | Mallory-Weiss tear | All other diagnoses (oesophagitis, gastritis, peptic ulcer, varices) | Malignancy | |

| Signs of bleeding | None | Adherent clot, spurting bleeding |

Low (0–2), intermediate (3–4) or high (≥5) mortality.

After effective endoscopic therapy, the administration of a PPI (80mg intravenous bolus followed by a continuous 8mg/h infusion) has been shown to reduce rebleeding, the need for surgery and mortality in patients at high risk of rebleeding (SR: strong; QE: high).51 A bolus of intravenous PPI could equally be administered within 72h of conducting the endoscopy.52 Alternatively, high oral doses could be administered if the patient is ready to begin an oral diet (SR: weak; QE: moderate).53 High PPI doses can be maintained beyond the first 72h in patients at high risk of rebleeding. Patients with low-risk lesions can be administered a standard PPI dose once daily.

Rebleeding treatmentRebleeding is defined as the presence of haematemesis and/or melaena associated with signs of hypovolaemia (systolic blood pressure <100mmHg and/or heart rate >100 beats per minute) and/or anaemia (fall in haemoglobin levels >2g/l) in <12h. Endoscopic therapy is the first-choice treatment in patients who rebleed, irrespective of whether or not they have previously received treatment (SR: strong; QE: moderate). A single study published years ago clearly shows that a second round of endoscopic therapy could prevent surgery in more than 70% of patients who present rebleeding without increased mortality or complications. Nevertheless, it is recommended to discuss all patients who rebleed during hospitalisation with the surgical team (SR: strong; QE: low).54 Should the second endoscopic therapy fail, emergency salvage surgery or angiography with embolisation should be considered. Percutaneous angiography with supraselective embolisation of the bleeding vessel could be considered an alternative to surgery in patients refractory to endoscopic therapy or in cases when it cannot be used (SR: weak; QE: low).55

Centres without access to interventional radiology could opt for surgery or to transfer the patient to a specialist interventional radiology unit.

Use of antiplatelet drugs and anticoagulantsRestarting antiplatelet therapy early after controlling the bleeding reduces the risk of cardiovascular mortality without significantly increasing the risk of rebleeding. Antiplatelet therapy can be safely readministered from the third day after the endoscopy in patients with recent clinical signs of haemostasis, and immediately in the absence of clinical signs of haemostasis (SR: strong; QE moderate).56–59

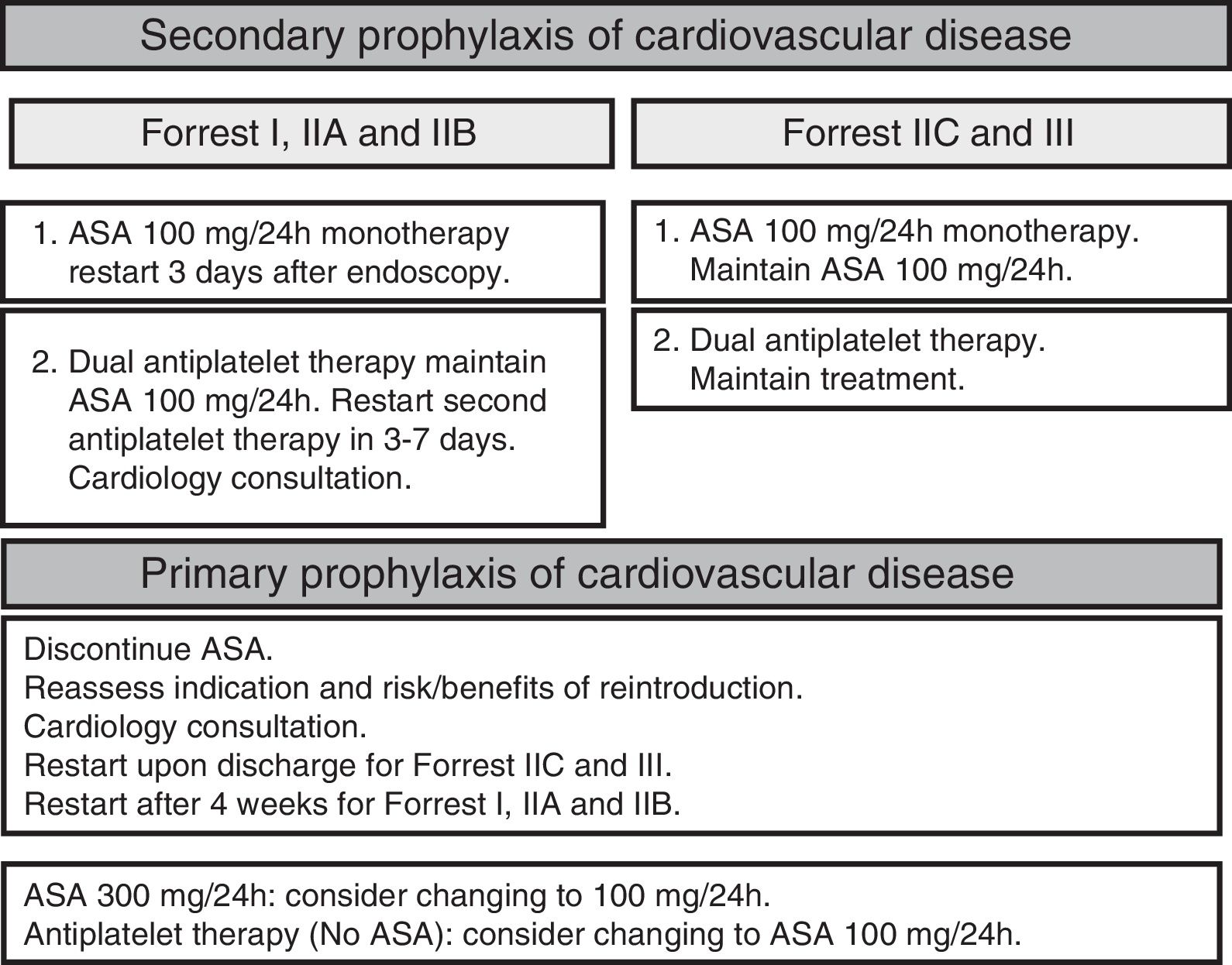

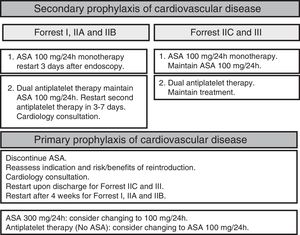

Patients on dual antiplatelet therapy are considered to be at high thromboembolic risk. It is recommended to continue antiplatelet treatment with acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) and to temporarily suspend clopidogrel as this does not significantly increase the risk of cardiovascular complications (SR: strong; QE moderate). In patients who have had a drug-eluting stent inserted within the last month, the decision of whether or not to maintain dual antiplatelet therapy should be taken with a cardiologist (Fig. 2).

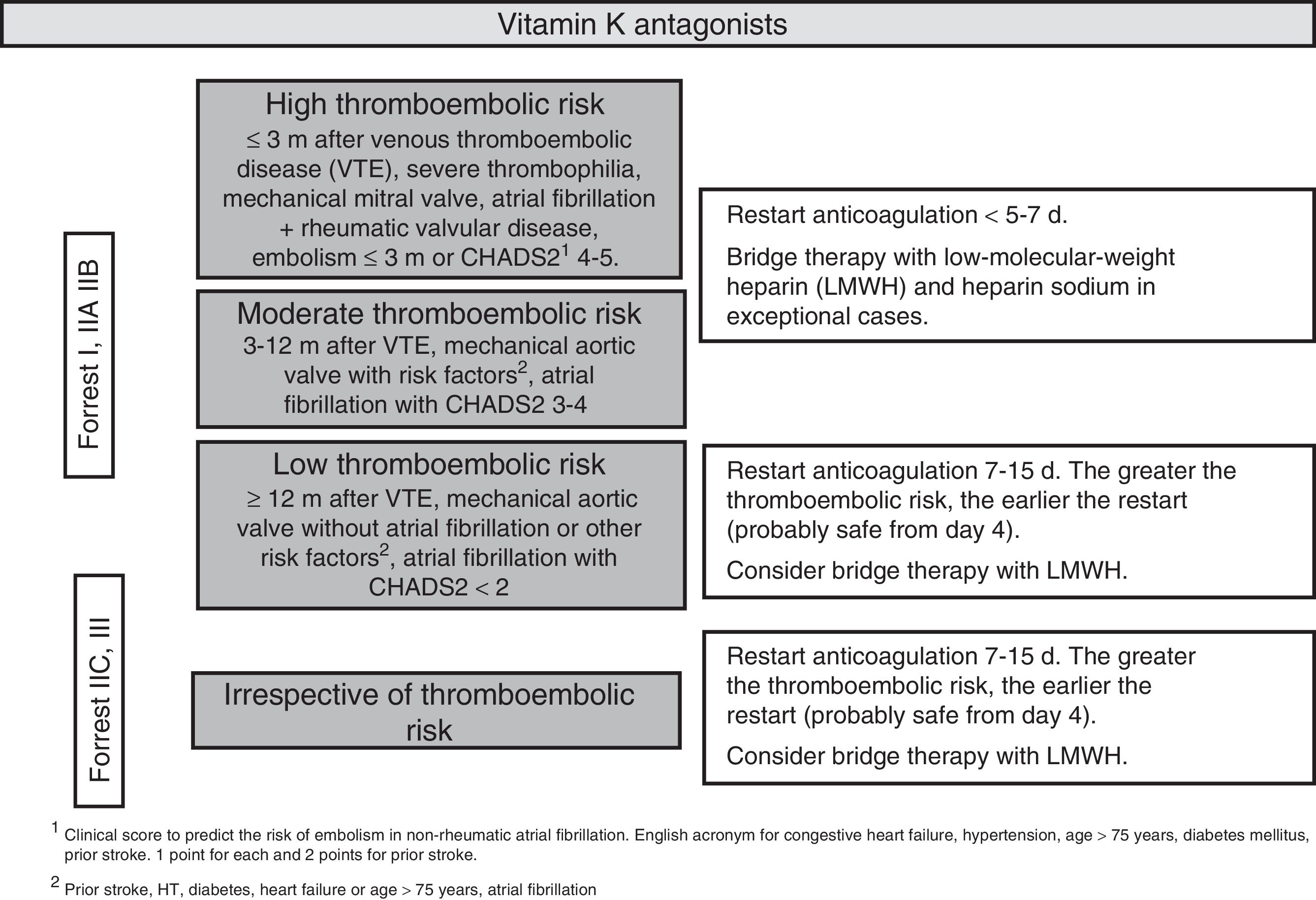

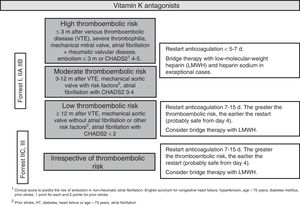

After an episode of UGIB, long-term anticoagulation therapy should be restarted as it decreases cardiovascular mortality. However, evidence supporting the best time to reintroduce anticoagulants is limited.60,61 After the endoscopy, the thromboembolic risk associated with the discontinuation of anticoagulants should be assessed on an individual patient basis. It is recommended to restart anticoagulation therapy 7–15 days after the bleeding episode. The risk of bleeding does not increase in this time frame, while the thromboembolic and mortality risk decreases.62 Restarting anticoagulation therapy during the first seven days could moderately increase the risk of bleeding but decrease the risk of thrombosis and thrombosis-related mortality.63,64 Patients with a moderate or high thromboembolic risk (Fig. 3) could benefit from restarting anticoagulation earlier (SR: strong, QE: moderate).65

It is recommended to administer low molecular weight heparin as bridge therapy during hospitalisation. Heparin sodium would only be indicated in exceptionally high-risk cases (e.g. caged-ball prosthetic mitral valves) (SR: strong; QE low).

It seems reasonable to administer DOACs in the same way as coumarin derivatives, although in these cases bridge therapy with heparin may not be necessary. Given the lack of data to establish a firm recommendation, all decisions should be taken together with a cardiologist. The possibility of switching to a new oral anticoagulant with a lower risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, such as apixaban or edoxaban, could be assessed after a UGIB episode (SR: strong; QE: low).66

Fig. 4 summarises hospital management of UGIB.

Post-discharge follow-upUlcer treatmentAfter discharge, patients with a gastroduodenal ulcer caused by Helicobacter pylori (Hp) should take a PPI in accordance with the prescribed eradication regimen.67 They should then continue to take a PPI for four weeks for a duodenal ulcer or for eight weeks in the case of a gastric ulcer (SR: strong; QE: high).68,69

For gastric ulcers of unknown cause, a PPI should continue to be taken until healing is confirmed by endoscopy. A double PPI dose is recommended for ulcers not infected by Hp in patients with no prior history of NSAIDs or antiplatelet drugs, or for refractory ulcers (SR: moderate; QE: strong).70

Differentiating between benign and malignant gastric ulcers is more difficult in UGIB, and biopsies should always be taken in the baseline endoscopy whenever possible. In any case, ulcer healing should be confirmed by biopsies even if the ulcer appears to have healed.71,72 A finding of no malignancy in the baseline pathology study could be a false negative in 2–6% of cases (SR: weak; QE: moderate).71–73 The endoscopy follow-up for gastric ulcers should be performed after six to eight weeks as most ulcers will be healed by standard PPI treatment during this time (SR: strong; QE: high).74

Helicobacter pylori infectionThe Hp infection must be examined early (acute phase) and after the appropriate antibiotic therapy in all patients with UGIB secondary to peptic ulcer (SR: strong; QE: high). The risk of rebleeding diminishes almost completely with Hp eradication.9,75–77

The rate of false negatives is high when the Hp detection tests are conducted during an acute bleeding episode. As such, these tests should be repeated when the initial result is negative (SR: strong; QE: high). The rate of false negatives arising from Hp diagnostic tests during bleeding episodes is high (25–55%).31,77,78 Performing an endoscopy during the bleeding episode enables the urease test (quick and simple) to be conducted, although diagnostic sensitivity is low in this scenario.79 It seems to be more beneficial in these cases to perform a histological examination of the gastric biopsies (antrum and body) as this method offers higher sensitivity, or to simultaneously conduct the urease and histology tests. For this reason, when the initial result is negative,80,81 Hp infection should be reassessed four to eight weeks after the acute episode using the 12C urea breath test in accordance with the European protocol, which includes the prior administration of citric acid.82 Although the Maastricht IV/Florence Consensus report also recommended the use of a stool antigen test (monoclonal ELISA)83 as a diagnostic alternative to the breath test, the reliability of the various stool tests varies depending on the manufacturer and the technique used, and the results in our setting are inferior to the breath test.84,85

Treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugsNo single NSAID has been shown to be superior to any other in terms of pain control efficacy, which means that in terms of clinical response alone, it is not possible to recommend a specific drug.86–88

However, two important aspects must be taken into account when recommending NSAIDs to patients with a history of UGIB: firstly, to carefully reassess the suitability of the NSAID indication; and secondly, the patient's cardiovascular and gastrointestinal risk. Patients with a history of UGIB will always be considered to be of high gastrointestinal risk, which means we only need to assess their cardiovascular risk.89

Most non-selective NSAIDs increase cardiovascular risk, and this is particularly true of diclofenac, with a relative risk (RR) of 1.40 (1.27–1.55; 95% CI). COX-2 inhibitors increase cardiovascular risk to a lesser extent, with an RR for celecoxib of 1.26 (1.09–1.47; 95% CI). The exception is etoricoxib, which has a thrombotic cardiovascular event risk profile comparable to diclofenac.90,91

The risk of gastrointestinal complications is halved with the use of selective COX-2 inhibitors versus non-selective NSAIDs. For example, the RR of diclofenac is 3.34 (2.79–3.99; 95% CI) versus the RR of celecoxib of 1.45 (1.17–1.81; 95% CI).92,93

As such, use of NSAIDs in high cardiovascular risk patients should be avoided as far as possible, administering low doses of celecoxib with a PPI if their use is absolutely essential. Celecoxib with a PPI should also be administered to low cardiovascular risk patients. This combination significantly reduces, although does not completely eliminate, the risk of rebleeding (SR: strong; QE: high).89,94–97

Treatment with acetylsalicylic acid and/or clopidogrelASA, clopidogrel, prasugrel and ticagrelor increase the risk of UGIB.98–100 Patients with a history of UGIB and taking any of these drugs should receive a PPI.101–104

Patients with UGIB who are taking clopidogrel to treat their cardiovascular disease are at a high risk of rebleeding, which is further increased when combining ASA with a PPI (SR: strong; QE: moderate).102

Various pharmacological studies have suggested that PPIs could competitively inhibit clopidogrel activation by the enzyme CYP2C19, increasing the risk of ischaemic events in patients treated with both a PPI and clopidogrel.105,106 In observational clinical studies, the clinical significance of the interaction between the two drugs has been contradictory.107 A recent meta-analysis of randomised clinical studies to assess the interaction between clopidogrel and PPIs found no differences in the onset of cardiovascular events, but demonstrated a significant reduction in the number of gastrointestinal bleeding episodes in the patient group treated with PPIs.108

The best quality evidence suggests that the pharmacological interaction between PPIs and clopidogrel has no relevant clinical implications. Therefore, the benefit derived from the secondary prevention of bleeding with a PPI clearly outweighs the cardiovascular risk that the interaction between PPIs and clopidogrel might entail (SR: strong: QE: moderate).108

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: García-Iglesias P, Botargues J-M, Feu Caballé F, Villanueva Sánchez C, Calvet Calvo X, Brullet Benedi E, et al. Manejo de la hemorragia digestiva alta no varicosa: documento de posicionamiento de la Societat Catalana de Digestologia. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:363–374.