Small bowel tumours are very rare, accounting for 1%–6% of all gastrointestinal (GI) cancers. Between 1% and 4% correspond to metastatic tumours, most commonly originating from malignant melanoma, lung cancer and colon cancer.1

Metastatic involvement of the small intestine is rare from a clinical point of view, but not so much from a histopathology perspective, with an incidence of 2%–14% according to autopsy series.2

The clinical manifestation of intestinal metastases is generally due to a complication of the disease, such as perforation, obstruction or active bleeding.3 Presence of any of these is associated with poorer prognosis of the underlying disease, and requires urgent surgical treatment.

We present 2 cases of patients with primary lung cancer who presented intestinal obstruction due to metastasis.

The first case, a 78-year-old man, smoker of 40 pack-years, was diagnosed with squamous cell lung cancer T2aN0M1 (hepatic) and treated with chemo- and radiotherapy. Nine months later, he presented to the emergency department for symptoms of bowel obstruction. Abdominal X-ray and computed tomography (CT) revealed dilatation of loops to the mid-jejunum with change in calibre secondary to adhesion or internal hernia. The patient underwent surgery, during which an obstruction was found in the jejunum as a result of a stenosing tumour. Complete resection and anastomosis were performed. Histopathology classified the tumour as squamous cell carcinoma metastasis. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 8. He continued with chemotherapy but died due to disease progression 20 months after the surgery.

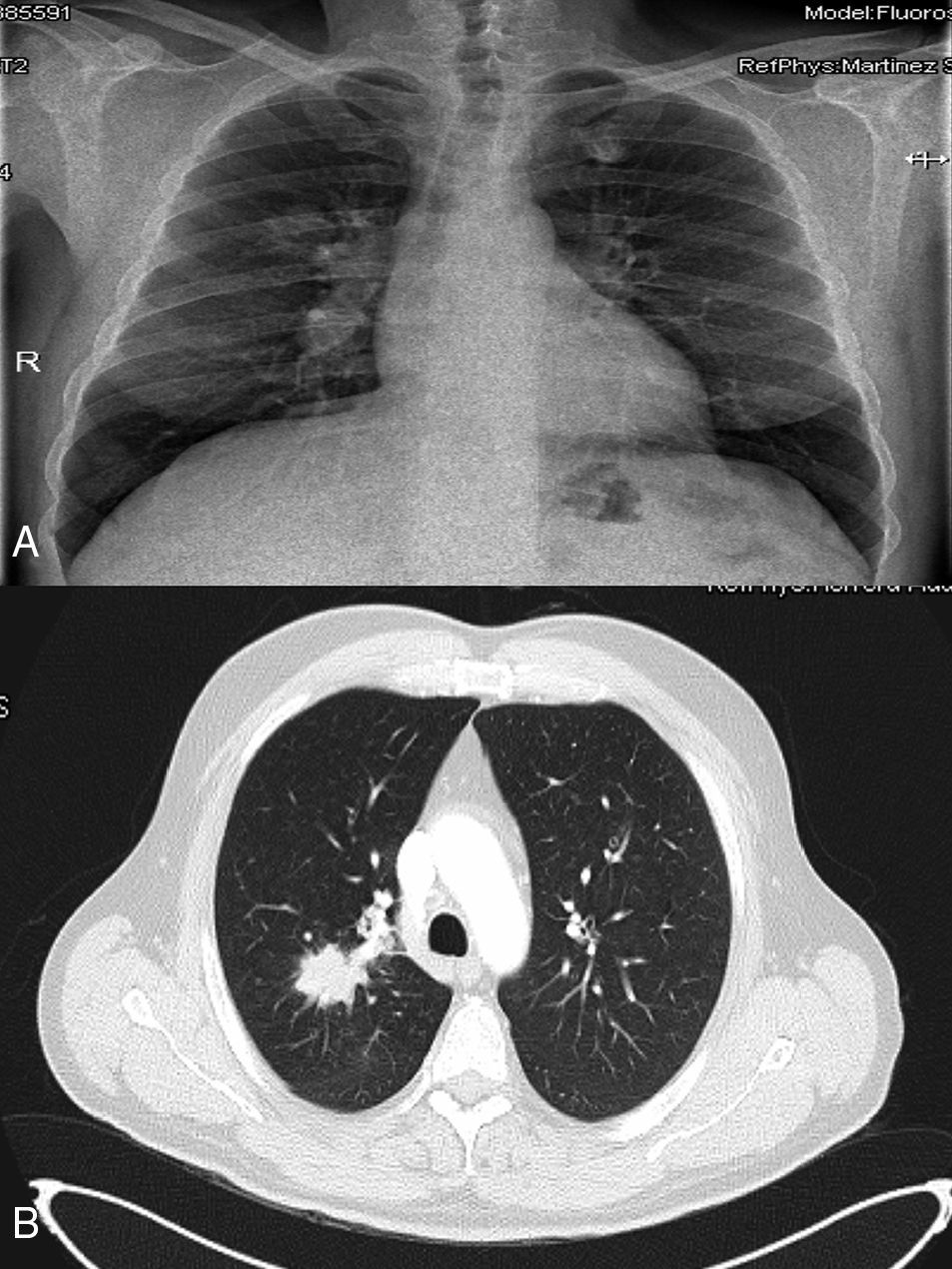

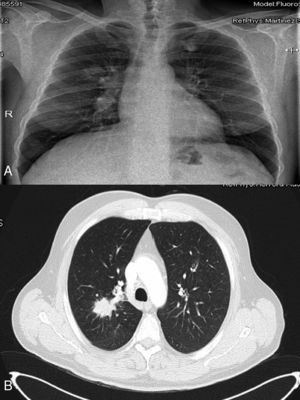

The second case, a 49-year-old man, smoker of 20 pack-years, was seen in the emergency department for abdominal pain. Abdominal CT (Fig. 1) showed a mass in the right iliac fossa with signs of necrosis and regional lymphadenopathies. Colonoscopy was performed due to suspected caecal cancer, with no evidence of lesions. However, a preoperative chest X-ray identified a poorly defined nodular image in the right upper lobe (Fig. 2A). A chest CT scan and bronchoscopy performed to complete the study showed a mass in the right upper lobe, with right hilar lymphadenopathies (Fig. 2B). Biopsy of the pulmonary and abdominal lesions identified small cell lung cancer. The patient was diagnosed with stage IV small cell lung cancer and treated initially with cisplatin-etoposide chemotherapy. After receiving the first cycle, he required urgent surgery due to a bowel obstruction secondary to the metastasis in the right iliac fossa affecting the terminal ileum. Complete resection of the tumour and ileocolic anastomosis were performed. The patient was discharged on day 7 post-surgery and recommenced chemotherapy treatment. Despite completing 6 cycles, disease progression was detected on the follow-up CT scan. Now, 9 months after diagnosis, he is receiving second-line chemotherapy, with stable disease.

Abdominal computed tomography, with oral and intravenous contrast. A large mass measuring 10.2×8.8cm can be seen in the right iliac fossa, affecting the terminal ileum and adjacent distal ileal loops; it also appears to encompass the appendix, with lateral displacement of the caecum. The inside of the mass shows fluid and oral contrast content, with air bubbles, probably due to necrosis and ulceration.

(A) Chest X-ray: mass in right upper lobe. (B) Computed tomography with oral and intravenous contrast, where a poorly defined mass with spiculated margins can be seen (measuring 50×27mm in axial plane), extending from the right hilar region with obstruction of the right superior lobe bronchus and posterior segmental bronchus, associated with right hilar lymphadenopathies.

More than half of lung cancers present distant metastases at the time of diagnosis,4 most often in the lymph nodes, liver, adrenal glands, brain and bone. The most common GI site for metastasis is the oesophagus, due to local infiltration. Intestinal metastases are rare, although more common than initially thought. They are most often located—in order of frequency—in the jejunum, ileum and duodenum.3

The most common histology of the primary lung tumour in our setting is adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, in similar proportions (23.5% and 22.7%, respectively),1,3 followed by large cell carcinoma (20.6%) and small cell carcinoma (19.6%).3

They are usually asymptomatic or generate non-specific symptoms such as anorexia and abdominal distension or pain, so clinical symptoms are sometimes difficult to distinguish from the effects of chemotherapy when the patient is already on treatment for their lung disease. Progression of the lesions leads to acute abdomen due to perforation, obstruction or haemorrhage.5 Manifestation prior to diagnosis of the primary tumour is unusual,4,5 although this occurred in one of our cases where the lung cancer was diagnosed during the preoperative study of the abdominal mass, considered as the primary tumour.

Diagnosis is usually made during surgery. Imaging techniques such as oesophago-gastro-duodenal transit, endoscopic capsule or CT can aid in the preoperative diagnosis, although they have low sensitivity in the detection of small intestinal lesions. Systematic use of positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) in lung cancer staging could help diagnose these small lesions, although there is still no conclusive evidence of its sensitivity. Definitive diagnosis is usually obtained by histopathology studies with the support of immunohistochemistry techniques for TTF-1, CDX2, CK7 and CK20, which can differentiate between primary and metastatic adenocarcinoma.5,6

The treatment of choice is resection of the affected area, with palliative intent. Intestinal metastases represent an advanced stage of the disease; they are generally associated with the presence of metastases in other locations, and indicate a poor prognosis, with maximum survival of 4 months.1,5 However, in certain patient series (prior surgery of the primary tumour, single metastases) where the small bowel metastases have been resected, patients have presented longer survival (6–8 months); cases of prolonged survival have also been reported, as happened in one of our patients.5,6

Advances in the systemic treatment of advanced stage lung cancer have managed to prolong survival in these patients, and consequently increase the likelihood of these types of complications. This heightens the importance of diagnosing intestinal metastases before their clinical expression, which could result in a relatively early diagnosis of the intestinal metastasis. Early surgical management of these lesions can help increase the survival of certain patients (low tumour burden, good general health) and prevent serious associated complications. The routine use of PET-CT in lung cancer staging will likely continue to increase the diagnosis of asymptomatic intestinal metastases, so the above should be taken into account in therapeutic decisions.

Thus, when non-specific bowel symptoms, anaemia or GI bleeding are found in a patient with a history of primary lung cancer, the possibility of intestinal metastatic disease should be considered as a possible cause. The appropriate diagnostic tests should then be performed, which can improve the prognosis by permitting complete resection of the lesion while the patient is in a better clinical condition, and preventing subsequent complications.7

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Please cite this article as: Romera-Barba E, Castañer-Ramón-Llín J, Navarro-Garcia I, Carrillo López MJ, Sánchez Pérez A, Vazquez-Rojas JL. Obstrucción intestinal por metástasis de cáncer de pulmón. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:466–468.