The study aimed to establish recommendations and quality criteria to enhance the healthcare process of PBC.

Patients and methodsIt was conducted using qualitative techniques, preceded by a literature review. A consensus conference involving five specialists in the field was held, followed by a Delphi process developed in two waves, in which 30 specialist physicians in family and community medicine, digestive system and internal medicine were invited to participate.

ResultsSeven recommendations and 15 sets of quality criteria, indicators and standards were obtained. Those with the highest consensus were «Know the impact on the patient’s quality of life. Consider their point of view and agree on recommendations and care» and «Evaluate possible fibrosis at the time of diagnosis and during PBC follow-up, assessing the evolution of factors associated with poor disease prognosis: noninvasive fibrosis (elastography > 2.1 kPa/year), GGT, ALP and bilirubin annually», respectively.

ConclusionsThe implementation of the consensus recommendations and criteria would provide better patient care. The need for multidisciplinary follow-up and an increased role of primary care is emphasized.

El estudio busca establecer recomendaciones y criterios de calidad para mejorar el proceso asistencial de la colangitis biliar primaria (CBP).

Pacientes y métodosEstudio llevado a cabo mediante el uso de técnicas cualitativas, precedidas por una revisión bibliográfica. Se realizó una conferencia de consenso en la que participaron cinco especialistas en la materia, seguida de un método Delphi desarrollado en dos olas al que se invitó a participar a 30 facultativos expertos en Medicina Familiar y Comunitaria, Aparato Digestivo y Medicina Interna.

ResultadosSe obtuvieron siete recomendaciones y 15 conjuntos de criterios de calidad, indicadores y estándares. Aquellas con mayor consenso fueron «conocer el impacto sobre la calidad de vida del paciente, tener en cuenta su punto de vista y acordar recomendaciones y cuidados» y «analizar la posible fibrosis en el momento del diagnóstico y durante el seguimiento de CBP, evaluando la evolución de los factores asociados con el mal pronóstico de la enfermedad: fibrosis de manera no invasiva (elastografía > 2,1 kPa/año), gamma-glutamil transferasa (GGT), fosfatasa alcalina (FA) y bilirrubina anualmente», respectivamente.

ConclusionesLa aplicación de las recomendaciones y criterios consensuados proporcionaría una mejor atención al paciente. Se subraya la necesidad de un seguimiento multidisciplinar y un mayor papel de la atención primaria (AP).

Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) is a chronic liver disease of unknown aetiology which progressively destroys the small bile ducts. The presence of autoantibodies in the blood of patients with this disorder suggests that the origin of the damage is autoimmune.1 However, recent studies suggest that immune-mediated impairment of the bile ducts may be secondary to a defect in bicarbonate secretion by biliary epithelial cells,2 specifically by predisposing them to cell deterioration as a consequence of attack by hydrophobic bile acids.3 A combination of genetic and environmental factors is thought to trigger the disease, which affects females more than males (9:1).

In most cases PBC is asymptomatic and is detected by abnormal liver function tests, mainly alkaline phosphatase (ALP).4 Without treatment, PBC slowly progresses (approximately 20 years), with the development of fibrosis and cirrhosis. However, in males the condition is very often more aggressive, with a poorer response rate and a higher incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma.5

For the diagnosis of PBC at least one of the following criteria have to be met: 1) elevated ALP and positive antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA) (present in >90% of patients); 2) increased ALP and PBC-specific antinuclear antibodies (Sp100 or gp210); or 3) increased ALP and compatible liver biopsy. There is currently no cure for PBC, but available therapies can delay liver damage, especially if treatment is started early. For this reason, early detection of patients suffering from PBC is crucial to increase their life expectancy and quality of life.6 However, there is limited access to AMA and/or specific ANA testing in primary care (PC), which delays the diagnosis.

Although the incidence of PBC is progressively increasing, it remains a minority disease, with an estimated prevalence in southern Europe of 27.9 patients per 100,000 people,7 although it varies according to the different geographical areas. It is worth mentioning that some of the symptoms often associated with PBC can have a significant impact on the sufferer's quality of life; Seventy-eight percent may experience asthenia at some point during the course of the disease and up to 70% may develop pruritus.8 These symptoms, mainly pruritus, become difficult to manage and clinically challenging, and delay in diagnosing PBC and starting the patient on targeted treatment will reduce their quality of life and overload the system due to the need for multiple outpatient consultations.

Not only must the necessary diagnostic tools be provided to identify affected patients, but proper use of these tools must also be encouraged. It is essential to promote an adequate level of awareness in the medical community about the existence of this disorder and the availability of therapeutic options which can drastically improve the prognosis of these patients. The need to increase awareness and understanding of the disease is highlighted by a recent Spanish study which revealed that up to 15% of patients with PBC were undiagnosed and lost in the system.9 Moreover, sufficient data was available to be able to make the diagnosis without any additional testing. It is important to stress that these “lost” patients tend to have more advanced fibrosis, which therefore means a worse prognosis and so requires the earliest possible intervention. Consequently, in addition to a greater awareness on the part of the medical profession, it is important to have adequate structuring of the care procedure.8,10 The management of such a process in the context of PBC should incorporate elements that allow for evidence-based monitoring of the quality levels of healthcare support received by these people.11

Within this framework, we planned this study with the aim of providing recommendations to improve the care process for PBC and shorten the time it takes to diagnose and manage the disease, in order to establish quality criteria and indicators to help monitor the care received by these patients, so action can be taken to optimise that care if necessary.

MethodsQualitative study based on the application of unanimity search methods,12,13 within the framework of a quality assurance action, involving healthcare professionals from the disciplines directly involved in the diagnosis and treatment of PBC. The qualitative methods used were first the consensus conference14 and then the Delphi method.15 Qualitative methods were chosen because they allow for a more in-depth exploration of the aspects to be studied. Similarly, they make it possible to capture nuances and contextual factors which are beyond the scope of quantitative techniques, and to reach agreement among experts in a field where there is no body of evidence. Such a conference is one of the most widespread processes for the development of medical recommendations and guidelines.16 The choice of the Delphi method responded to the need to reach consensus on criteria for practice, determining the degree of accord among experts to agree on specific criteria for PBC.

The leadership of this study was carried out by a panel of experts, including three specialists in Family and Community Medicine and two in Hepatology dedicated to cholestatic and autoimmune liver diseases, along with four experts in qualitative research methods (all with at least eight years of professional experience and significant contributions to scientific journals and congresses). The research was conducted from April to December 2022.

Consensus conferenceThe members of the expert panel took part in this technique. It consisted of a debate led by a moderator based on scripted questions previously prepared by the research team, in which each of the proposals made by the participants were debated and agreed on. It was conducted in three stages, with the aim of putting forward a list of initial ideas for both recommendations and quality criteria in the diagnosis and treatment of PBC. Initially, online, synchronously, we presented the study and defined the milestones to be achieved and a first list of questions to be included in the debate, which took place from 19 to 27 April. For this purpose, we circulated and used the results of a scoping review of the literature using the PubMed database. In this case, we used the combination of the following: Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) descriptors: Primary Biliary Cirrhosis, Primary Biliary Cholangitis, Quality of healthcare and Quality indicators. Information was extracted from articles registered in English or Spanish, with no time limit. In a second phase, from 19 May to 2 June, asynchronously online, the questions on the first list were defined and clarified, with the experts incorporating clarifications and suggestions, clarifying those aspects that were recommendations and those that could form part of the list of indicators. Then, in a third, synchronous face-to-face session on 7 June, a debate session was held with the final aim of reaching a consensus on a definitive proposal for the recommendations and quality criteria that would subsequently form part of the Delphi method questionnaire 0.

Delphi methodThirty Spanish National Health System healthcare professionals from different autonomous regions and from the specialities of Family and Community Medicine, Gastroenterology and Internal Medicine (autoimmune) were invited to answer questionnaire 0 (Appendix A). Initially, a list of potential participants was drawn up on the basis of the recommendations provided by the expert panel. Each was asked to suggest a minimum of 10 people who met the following inclusion criteria: 10 or more years of professional experience and with publications, papers or lectures at conferences in their specialist areas. A preliminary list was obtained containing 59 candidates. In order to ensure the representativeness of the sample and to eliminate any potential bias, a randomisation was carried out among the proposed physicians, with the aim of selecting a total of 30 people who would finally make up the final lists of participants in the study.

To facilitate collaboration, a specific online platform for Delphi17 studies was made available. Invitations to participants were issued by the Sociedad Española de Calidad Asistencial (SECA) [Spanish Society for Healthcare Quality]. Each received a personal invitation with instructions and conditions of access, specifying the expectation of a minimum of two to a maximum of four rounds, depending on the degree of consensus reached after successive phases of participation. They all gave their prior consent to take part in this study and sufficient unanimity was achieved in the second round of participation. There was an interval of approximately one month between each of the two rounds. The survey was conducted from 11 October to 7 November 2022. The second from 21 November to 13 December 2022.

Questionnaire 0 was structured in two blocks: 1) recommendations; and 2) quality criteria, indicators and standards. The first covered general aspects and “don'ts” and addressed key elements in the relationship with patients. This block was assessed on a scale from 0 (minimum value) to 10 (maximum value) for each of the following criteria: importance of the recommendation; frequency in the centre's routine clinical practice; and applicability in the health clinic.

The block of quality criteria, indicators and standards was assessed with respect to the importance of each judgement on a scale of 0 (minimum value) to 10 (maximum value), whether the indicator was currently monitored in the centre with a dichotomous answer of yes/no or the option of having no information on it; whether it could be measured from the available information systems with a dichotomous answer of yes/no or the option of having no information on it; and to what extent the proposed standard was considered realistic on a scale of 0–10. Also, if any of the participants had any suggestion on the wording for a new contribution, they could propose it in an open field. This information was used in the second round.

Three levels of unanimity were established for accepting or eliminating elements: those with a high consensus score for integrating the proposal into the set of recommendations or indicator scorecard; those with a very low score agreed for outright discarding the suggestion or indicator scorecard; and unclear consensus, elements that were subjected to a second round of voting to clarify whether they should be included in the recommendations or indicator scorecard because the scores given were unclear. Tables 1 and 2 show the analysis criteria for awarding levels of consensus with their corresponding cut-off points, both for the block of suggestions and for the indicator scorecard. The results were reviewed by the panel of experts of this study, who were allowed, according to their experience and clinical practice, to incorporate recommendations which in their opinion should be part of the final list.

Cut-off points used in the two waves in the indicator scorecard block.

| Wave | Consensus level | Column ≥ 8 (questions 0−10) | % Yes (yes/no questions) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 | Acceptance | Importance criterion > 80% | |

| Rejection | Importance criterion < 65% | Indicator feasible < 50% | |

| Wave 2 | Acceptance | Importance criterion > 80% | |

| Rejection | Does not meet the acceptance criterion |

The starting point was an initial list of 102 suggestions or quality criteria which were complemented in the expert panel discussions by covering the different milestones or critical moments in the care process. Initially, they were divided into eight categories: knowledge of the disease and resources (22 recommendations); diagnostic protocols (26); management, diagnosis and follow-up from PC (15); referral to specialists (4); waiting times (14); accessibility to diagnostic tests from different levels (4); coordination between hospital care and PC specialists (13); and other aspects related to early detection and management of the disease (4). In a second round of the consensus conference, the proposals were finalised by defining three blocks of recommendations, consisting of general (8), on the relationship with patients (17) and “don'ts” (17); in addition to 17 quality criteria and 13 standards. In the last phase of the conference, which was held in-person, a set of suggestions and lists of indicators were finalised, which gave rise to the Delphi questionnaire 0.

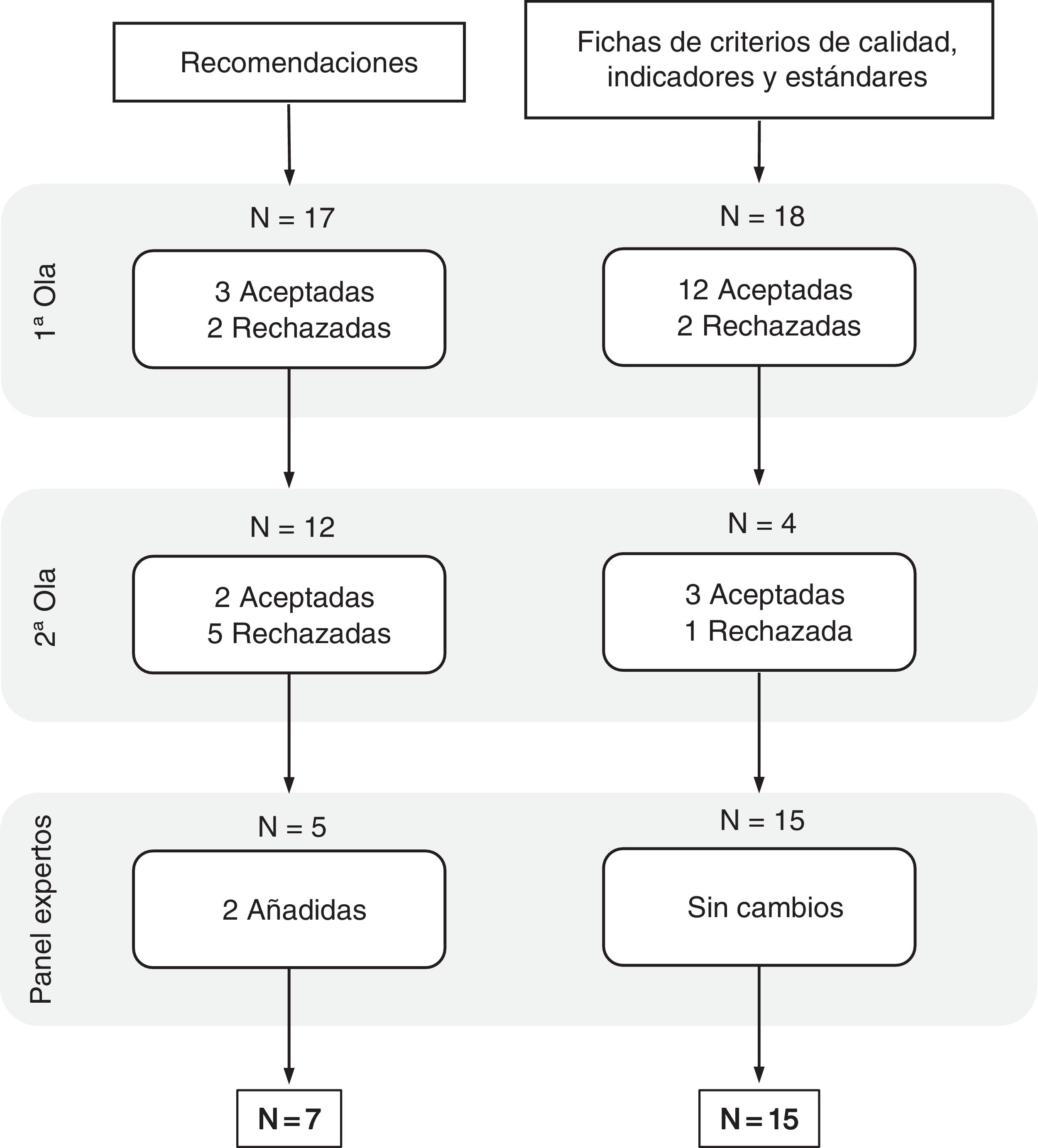

Delphi methodQuestionnaire 0 consisted of 17 recommendations and 18 lists covering the quality criteria, together with their corresponding indicators and standards.

The participation rate in both waves was 96.6% (n = 29), distributed as shown in Table 3.

Percentage of participation, both in the first and second wave, distributed by professional profile.

| Profile | No. of invitations | No. of responses | % Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Medicine (autoimmune) | 3 | 3 | 100% |

| Gastroenterology | 7 | 7 | 100% |

| Hepatology | 11 | 10 | 90.9% |

| Family and Community Medicine | 9 | 9 | 100% |

| Total | 30 | 29 | 96.6% |

At the end of the second round, a consensus proposal of seven recommendations and 15 lists with corresponding quality criteria, indicators and standards was obtained (Fig. 1). Both the suggestions (Table 4) and the lists of indicators (Table 5) were prioritised according to the criteria set by the expert panel. The data corresponding to the descriptive results for each element in the first and second phase can be found in Appendices B and C respectively.

Recommendations selected after the second round, ordered from most to least important, and in case of equal scores the applicability criterion in the centre is selected.

| Recommendation | Importance of the recommendation ≥ 8 (%) | Applicability in the healthcare facility ≥ 8 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Knowing the impact on the patient's quality of life, taking into account the patient's point of view and agreeing on recommendations and care | 100% | 75.9% |

| Facilitate communication between PC doctors and Hepatology or Gastroenterology doctors to improve patient follow-up and ensure continuity of care* | 100% | 72.4% |

| Inform and train PC and Gastroenterology doctors about PBC and its early detection, diagnosis and therapy, determination of the risk of disease progression, symptom management and treatment of complications | 96.6% | 79.3% |

| Establish collaborations between PC, Hepatology and Gastroenterology specialists and patient associations* | 96.6% | 44.8% |

| Have clinical guidelines specifying the diagnostic algorithm for patients with elevated ALP with or without associated symptoms, and the criteria for referral to Hepatology or Gastroenterology | 93.1% | 89.7% |

| Have access from PC to request complete liver function tests with AST, ALT, ALP, GGT, bilirubin (direct fraction if elevated), determination of AMA and ANA, and abdominal ultrasound | 93.1% | 82.8% |

| Perform the appropriate liver disease investigations for the patient's clinical situation, which would include as a minimum the determination of AMA (and PBC-specific ANA) in the case of patients with predominantly cholestatic liver profile abnormalities | 93.1% | 82.8% |

ALP: alkaline phosphatase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AMA: antimitochondrial antibodies; ANA: antinuclear antibodies; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; GGT: gamma-glutamyl transferase; PBC: primary biliary cholangitis; PC: primary care.

Quality criteria, indicators and standards selected after round two.

| Criteria, indicators and standards | Importance of criterion ≥ 8 (%) | Indicator feasible (%) | Standard realistic ≥ 8 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria: analyse possible fibrosis at diagnosis and during follow-up of PBC, assessing changes in factors associated with poor prognosis of the disease: fibrosis, non-invasively (elastography > 2.1 kPa/year), GGT, ALP and bilirubin annually | 96.6% | 75.9% | 79.3% |

| Indicator: percentage of patients with PBC who have an assessment of fibrosis both at diagnosis and during follow-up visits by annual elastography, GGT, ALP and bilirubin | |||

| Standard: of patients diagnosed with PBC, 100% should have fibrosis assessment performed at diagnosis and during follow-up by annual elastography, GGT, ALP and bilirubin | |||

| Criterion: ensure an adequate differential diagnosis in patients treated as having overlap syndrome | 96.6% | 65.5% | 72.4% |

| Indicator: percentage of patients correctly diagnosed as having overlap syndrome | |||

| Standard: of patients with autoimmune association, 100% are correctly diagnosed as having overlap syndrome | |||

| Criterion: ensuring therapeutic adherence to UDCA treatment in PBC patients | 96.6% | 62.1% | 82.8% |

| Indicator: percentage of PBC patients who receive the correct dose of UDCA | |||

| Standard: at least 80% of patients must be correctly treated with UDCA | |||

| Criteria: if PBC is suspected, the patient has to be referred to a specialist in Hepatology or Gastroenterology and be seen in that department within a period of no more than two months | 93.1% | 82.8% | 37.9% |

| Indicator: percentage of patients seen within two months in the Hepatology/Gastroenterology department/unit | |||

| Standard: at least 90% of patients should be seen by Hepatology/Gastroenterology within two months of referral | |||

| Criterion: patients on treatment for PBC should have assessed response to treatment one year after starting treatment | 93.1% | 79.3% | 79.3% |

| Indicator: percentage of patients assessed with some treatment scale one year after starting treatment | |||

| Standard: 100% of patients should be assessed with some treatment scale one year after starting treatment. | |||

| Criterion: AMA-negative patients with high clinical suspicion have specific ANA findings | 93.1% | 79.3% | 75.9% |

| Indicator: percentage of patients with negative AMA and high clinical suspicion who have specific ANA findings | |||

| Standard: of patients with negative AMA and high clinical suspicion, 100% should have had specific ANA tests | |||

| Criterion: patients who have not responded to or have not tolerated the first line of treatment have the second line of treatment | 92.9% | 71.4% | 65.5% |

| Indicator: percentage of patients with second-line treatment | |||

| Standard: at least 90% of patients who do not respond to or tolerate first-line treatment should have second-line treatment | |||

| Criterion: channels should be in place to allow direct communication between PC and Hepatology/Gastroenterology | 89.7% | 86.2% | 69.0% |

| Indicator: existence of formal structures to enable this communication (e-consultation, inter-consultation, joint working groups) | |||

| Standard: have at least one type of formal structure in place to enable this communication | |||

| Criterion: all AMA-positive patients a should be assessed by Hepatology/Gastroenterology | 89.7% | 69.0% | 65.5% |

| Indicator: percentage of AMA-positive patients who have been assessed by Hepatology/Gastroenterology | |||

| Standard: 100% of AMA-positive patients should have been assessed by Hepatology/Gastroenterology | |||

| Criterion: patients with PBC should be assessed for extrahepatic symptoms (pruritus, fatigue) at follow-up visits | 89.7% | 62.1% | 79.3% |

| Indicator: percentage of patients with assessment of extrahepatic symptoms (pruritus, fatigue) at follow-up visits | |||

| Standard: at least 80% of patients assessed for extrahepatic symptoms at follow-up visits | |||

| Criterion: patients with PBC should be properly vaccinated according to the vaccination schedule and additionally with hepatitis A and B and pneumococcus | 89.7% | 62.1% | 69.0% |

| Indicator: percentage of patients with PBC vaccinated according to the vaccination schedule and additionally with hepatitis A and B and pneumococcus | |||

| Standard: at least 80% of PBC patients should be vaccinated according to the vaccination schedule and additionally with hepatitis A and B and pneumococcus | |||

| Criterion: patients with PBC should have the disease correctly recorded in their MR according to ICD-10 (K74.3) | 86.2% | 82.8% | 69.0% |

| Indicator: percentage of patients with PBC who have the disease correctly recorded in their MR using code K74.3 (ICD-10) | |||

| Standard: of patients with PBC, 100% must have the disease correctly recorded in their MR using the code K74.3 (ICD-10) | |||

| Criterion: liver ultrasound requested by PC cannot be delayed more than four weeks | 86.2% | 69.0% | 3.4% |

| Indicator: percentage of patients with ultrasound scan performed within four weeks | |||

| Standard: at least 90% of the patients must have been able to have the ultrasound within four weeks | |||

| Criterion: the initial investigations with blood tests including AMA and ANA and ultrasound in PC should not take more than six weeks | 86.2% | 58.6% | 27.6% |

| Indicator: percentage of patients with cholestasis who have a request for initial determinations of AMA, ANA and abdominal ultrasound | |||

| Standard: at least 90% of patients must have had the initial study within a maximum of six weeks | |||

| Criterion: bone disease assessment and follow-up with densitometry should be performed every two years in patients with PBC | 82.8% | 72.4% | 48.3% |

| Indicator: percentage of patients with bone disease assessment and follow-up with densitometry every two years | |||

| Standard: at least 80% of patients with assessment and follow-up of bone disease with densitometry every two years |

ALP: alkaline phosphatase; AMA: antimitochondrial antibodies; ANA: antinuclear antibodies; ICD: international classification of diseases; MR: medical records; PBC: primary biliary cholangitis; UDCA: ursodeoxycholic acid.

The results are shown in order of importance of the quality criteria. In the case of equal scores, the criterion is selected by whether or not it is feasible to measure the indicator, and if these are the same once again, by the degree to which the standard is considered realistic.

Among the 10 general recommendations proposed in questionnaire 0, after the two waves of participation, there were six that reached sufficient consensus to be considered elements which should not be left out of this panel. Proposals related to the importance of having self-reported measures of patients' quality of life or how communication between the two levels of care should be facilitated to ensure continuity of care stood out with broad unanimity. Furthermore, these measures exceeded their applicability by more than 70% in the centres above eight points (Table 4). The “don'ts” block of recommendations reached a low level of consensus in both importance and applicability and did not therefore form part of this group of final suggestions (Appendix A, Appendix B). Among those classified in relation to patients, the incorporation of patients' associations within collaborative teams between PC, hepatology and gastroenterology proved to be a very important proposal, but its applicability in healthcare centres above eight points was reduced to less than 50% acceptance (Table 4).

Criteria, indicators and standards for improving early diagnosis of primary biliary cholangitisOf the 18 lists of criteria, indicators and standards proposed in questionnaire 0, after the two waves of participation, 15 reached sufficient consensus to be considered as elements that should not be left out of the indicator scorecard. The most unanimous were focused on the definition of aspects related to diagnostic and referral criteria with the definition of their corresponding standards. In terms of considering the lists proposed as feasible and realistic were the areas where fewer of the scores reached 70% (Table 5). All the criteria proposed in these were considered important, with scores above 90% in virtually all cases. Those that were more related to length of delay, for example, for liver ultrasound or initial investigations with blood tests including AMA or ANA, or periods related to disease follow-up, although considered very important criteria, were to a lesser extent feasible and above all realistic (Table 5).

DiscussionThe recommendations, quality criteria, indicators and standards developed in this work are intended to assess the quality of care in this process and to improve the care provided to patients with PBC. Decisions taken took into consideration the impact on the person's quality of life, the capacity for early detection, the role of PC in early identification and evidence-based therapeutic approach, and the provision of patient-centred care.18 As far as we have been able to ascertain during the course of this study, the proposed quality indicators are not routinely measured in the centres. Monitoring of these indicators would be a step forward in terms of safeguards for patients with PBC, in line with practice guidelines.6,8,10

The participants identified difficulties in early diagnosis of PBC as the main barrier to quality of care. This means involving the first level of care,4 providing it with information and capacity for action, but also ensuring the adequacy of communication channels between levels and establishing routes to ensure that referral is not delayed time-wise.

The results reflect the need for a multidisciplinary approach to PBC and to seek new ways to facilitate patient adherence to treatment.19 The therapeutic indication to reduce the risks of disease progression was also one of the agreed priorities.

At the organisational level, these results suggest that health services should rethink, in order to facilitate early identification of PBC, access from PC to request complete liver function tests with aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), ALP, GGT, bilirubin (direct fraction if elevated), the determination of specific AMA and ANA and an abdominal ultrasound.

In the clinic, there was a broad consensus that a diagnostic algorithm for patients with high ALP20 with or without associated symptoms and criteria for referral to hepatology or gastroenterology would increase quality. In this case, the liver disease investigations should include, as a minimum, the determination of AMA (and PBC-specific ANA) in the case of patients with predominantly cholestatic liver profile abnormalities. The participants stressed that protocols for the care of patients with PBC should ensure that those who have not responded to or tolerated first-line treatment are candidates for second-line treatment. Also that compliance with the vaccination schedule, particularly hepatitis A and B and pneumococcal vaccination, should be ensured.

As key elements to ensure the quality of care in PBC, the participants in this study have highlighted the assessment of fibrosis and extrahepatic symptoms, the appropriate differential diagnosis in patients treated as having overlap syndrome and the importance of adequate recording of the disease in the patient's medical records (MR). They also stressed the need for all AMA-positive subjects to be assessed by Hepatology/Gastroenterology and for specific ANA testing to be performed in those with negative AMA and a high degree of clinical suspicion. Medical services need to review their protocols and agendas to address this criterion.

Regarding the relationship and communication with patients, the participants invite reflection on the measures currently in place to ensure adherence to treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA). In light of the debate, it should not be left to the subjects alone and protocols should be revised to include measures to strengthen communication with patients about PBC, for example, through negotiation processes based on techniques such as motivational interviewing.21

The agreed criteria, indicators and quality standards allow the monitoring of the quality levels of care for patients with PBC by the units and services. They also form the basis for establishing a quality standard, for example, as part of an accreditation process, to drive improvements in diagnostic and therapeutic procedures.

Although discussions were energised and individual work was encouraged to reduce the impact of possible biases due to dominant experts or peer pressure, it was possible that some of the proposals were overvalued or that some of the participants did not express opposing views. Professionals from different health services were invited in order to respect the diversity of procedures for the care of patients with PBC. However, not all regional health services were represented.

Author contributionsJ.J. Mira and M. Santiñá came up with the concept of the study and participated in implementation of the study, data analysis and the writing of a first draft. Á. Díaz-González, N. Fontanillas, M.C. Londoño, M. Noguerol, F. Pérez Escanilla gathered data and interpreted results. E. Gil-Hernández and M. Guilabert conducted the qualitative techniques, analysed results and participated in the writing of the first draft. All authors reviewed, provided input for and approved the wording.

FundingThis work was supported by unrestricted funding from Advanz Pharma.

During the conduct of this study, JJM was awarded a research intensification contract from Instituto de Salud Carlos III [Carlos III Research Institute] (reference INT22/00012).

Ethical considerationsThe research was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. No patients took part and no patient data were used. This work is part of a consensus study among a panel of experts based on recommendations from scientific evidence and clinical practice within the framework of quality assurance.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.