We present the case of an 82-year-old male who attended the Emergency Department with haematemesis and melaena. His previous medical history included hypertension, atrial fibrillation on anticoagulant therapy, an operated abdominal aortic aneurysm and a previous episode seven months earlier of upper gastrointestinal bleeding caused by a Dieulafoy lesion (DL) in the gastric fundus, which had been treated by sclerosis and placement of endoclips.

On arrival at our hospital, the patient had blood pressure of 85/50mmHg, a heart rate of 120bpm and haemoglobin of 6.5g/dl, for which he was resuscitated with volume and transfusion of blood products. Subsequently, within the first 8h of the patient arriving in the emergency department, a gastroscopy was performed in which a large clot was identified adhered to the greater curvature-fundus. It was not possible to clearly visualise the focus of the bleeding, but it was treated by injecting adrenaline and polidocanol through the clot. Another gastroscopy was performed the next day, showing a clot of less than 1cm in size, as well as small adjacent punctate disruptions in the mucosa, probably corresponding to the sclerosis of the previous day and the endoclips placed in the previous admission. As there were no signs of re-bleeding and it was not possible to determine the exact point of origin of the bleeding, no treatment was carried out this time.

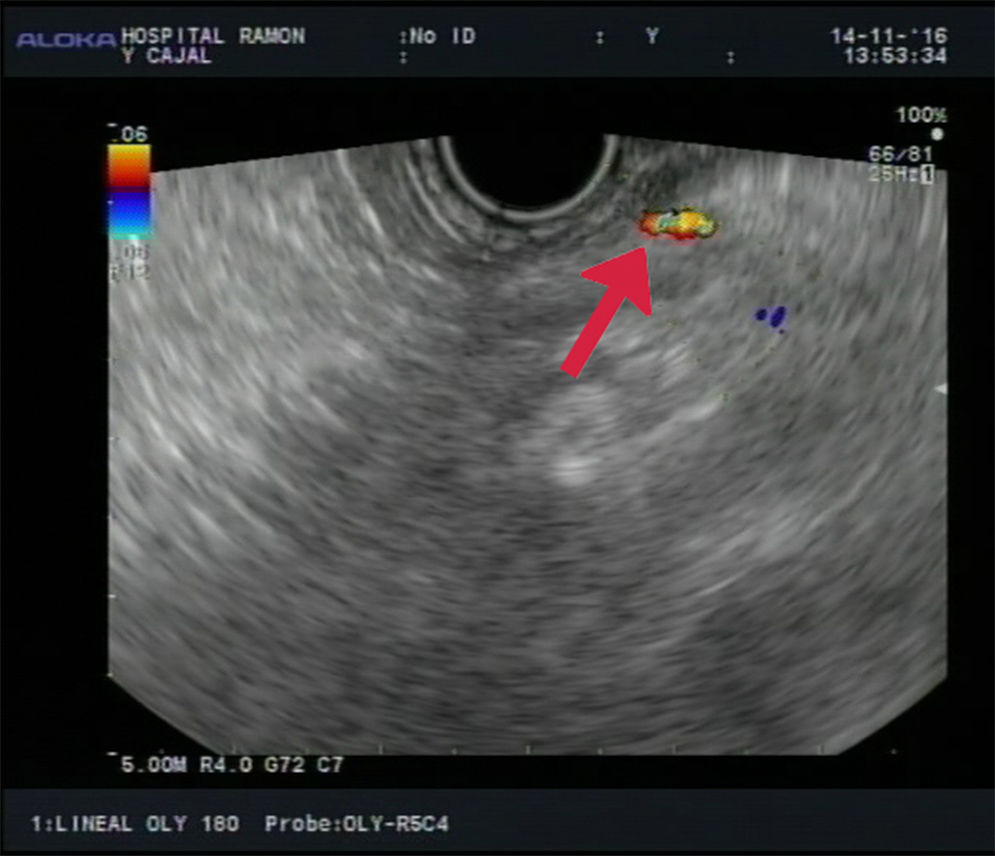

Back on the ward, the patient had melaena and anaemia once again. An endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) was performed in which a 2mm calibre vessel was identified coming through the stomach wall at the level of the gastric fundus, highly compatible with Dieulafoy's lesion (Fig. 1). The lesion was sclerosed using an endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided needle, injecting 0.5mg of adrenaline and 2cc of polidocanol, after which the flow at that level was seen to disappear. After that, over the next 6 months of follow-up, the patient had no external signs of bleeding and did not require further transfusions.

DL is a vascular malformation in the gastrointestinal tract, most commonly occurring in the stomach.1–4 It consists of a submucosal artery that is histologically normal but follows a tortuous path and does not undergo normal branching, thereby becoming 10 times larger than the normal calibre of the capillaries in the gastrointestinal mucosa.1,5–7

Although uncommon, DL is important as a serious cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, representing approximately 1–2% of cases.2,7 The aetiology and pathogenesis are unknown, although it typically affects adult males with multiple comorbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease.1,2 The use of NSAIDs has also been associated with DL, probably as a result of the ischaemia and atrophy they cause in the gastrointestinal mucosa, which makes bleeding in these patients more likely.1,6,8

DL can remain silent for years, starting in most cases as sudden-onset painless gastrointestinal bleeding, which can have high morbidity and mortality rates, and has a tendency to recur.2,4,5,8

Endoscopy is the diagnostic technique of choice in this disease.4,8 However, in up to 33% of cases, repeat endoscopies are needed to reach a definitive diagnosis,2,6,7 as DL can be difficult to detect if there is no active bleeding due to the small size of the lesion and the normal appearance of the surrounding mucosa.

From the point of view of treatment, endoscopy has proven to be a safe and effective technique, achieving primary haemostasis in 90–100% of cases.2 There are several endoscopic therapeutic options available,2,5,6 with better results reported with mechanical methods, as well as with combination therapy compared to monotherapy.2,4,8

However, despite advances in endoscopy in this field having led to a dramatic reduction in the mortality rate from DL-related bleeding (from 80% to 8%), relegating surgery to the background,4 the risk of re-bleeding in these patients is estimated to range from 9% to 40%.2

This makes the diagnosis and treatment of DL extremely challenging in a not insignificant number of cases, which explains the growing interest in the study of other minimally invasive techniques as alternatives to endoscopy, such as arteriography with selective embolisation4,7 or EUS.1,2,5,8

In recent years, EUS has been singled out as a technological resource of great utility in the management of DL,2,3,5,9 particularly in cases where endoscopy has previously failed. With Doppler ultrasound, the trajectory of the malformed submucosal vessel can be demarcated with great precision, and selective sclerosis performed on it by injecting substances such as adrenaline or ethanol.3,4,9 Furthermore, Doppler ultrasound can also be used to confirm successful ablation of the lesion after treatment, using Doppler to demonstrate absence of flow in the malformed artery.2,3

Our case provides a clear example of the role of EUS in the management of recurrent DL-related bleeding, as this was the decisive technique in our patient in controlling DL refractory to endoscopic treatment.

Please cite this article as: García de la Filia I, Hernanz N, Vázquez Sequeiros E, Tavío Hernández E. Hemorragia digestiva recurrente por lesión de Dieulafoy tratada con éxito mediante esclerosis guiada por ecoendoscopia. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:319–320.