Acute liver failure (ALF) is a rare condition with rapid onset and a high mortality rate characterised by coagulopathy, with INR>1.5, and any degree of encephalopathy in a patient without prior liver disease.1 Some of the most common causes are toxicity to drugs such as paracetamol, viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, Wilson's disease and ischaemic hepatitis.1,2 Although haematogenous spread of solid tumours often affects the liver, ALF caused by the spread of cancer is very uncommon, with few cases reported in the literature. In a study conducted in the United Kingdom over 18 years (1978–1995), this situation was documented in only 0.44% of patients, with cancers of haematological origin being the most common cause.3 In another more recent American multicentre study conducted by the Acute Liver Failure Study Group, which reviewed 1910 patients with ALF from 1998 to 2012, only 27 patients (1.4%) were identified with ALF secondary to tumour infiltration.4

The liver parenchyma is replaced by cancer cells which propagate sinusoidally, causing hepatocellular ischaemia and releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines. The increase in AST, LDH and hepatomegaly support this hypothesis; fulminant hepatic failure triggers multiple-organ failure, with a high mortality rate of 60–80%.5 The confirmation diagnosis is made by liver biopsy and in most cases is performed postmortem.3,6–9

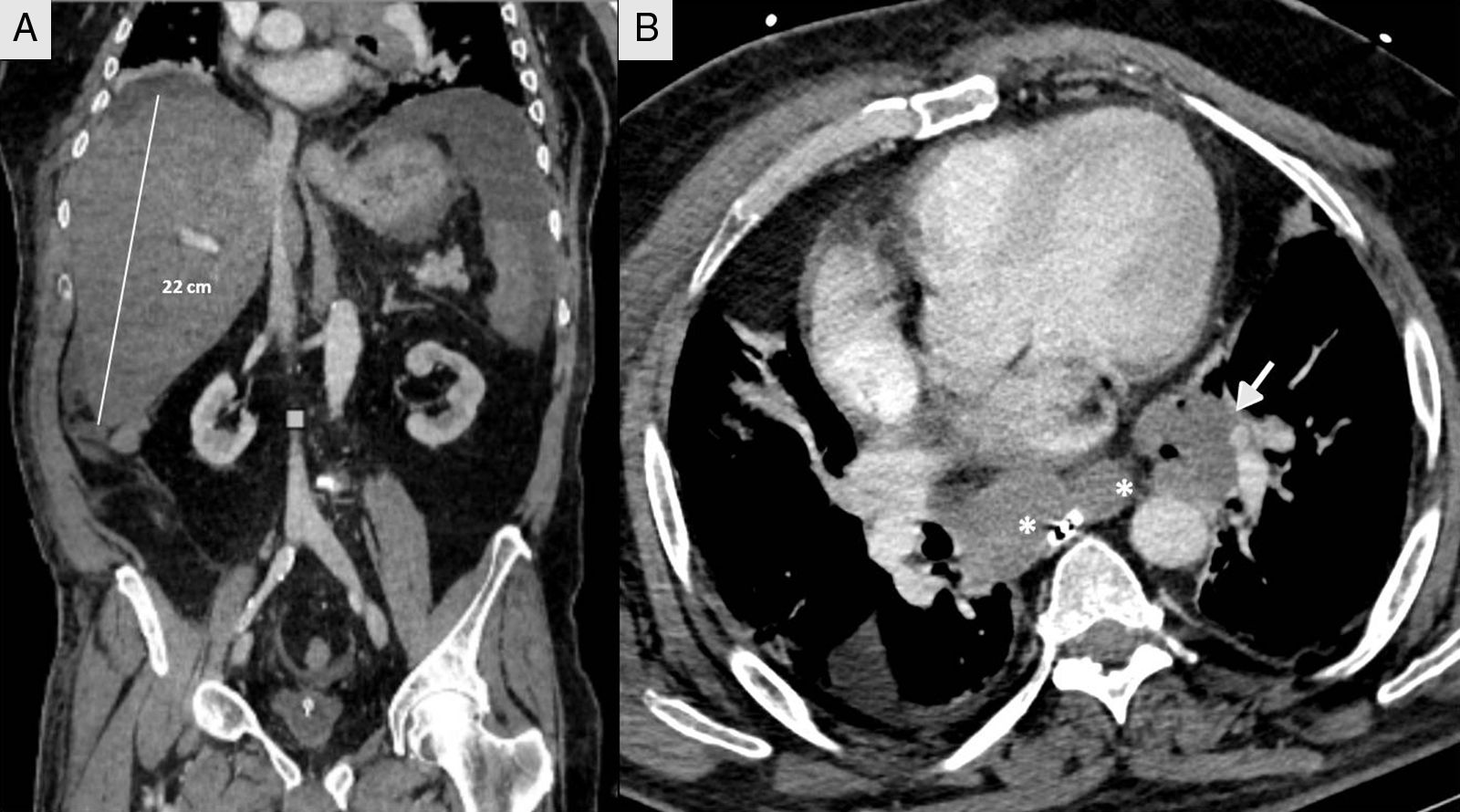

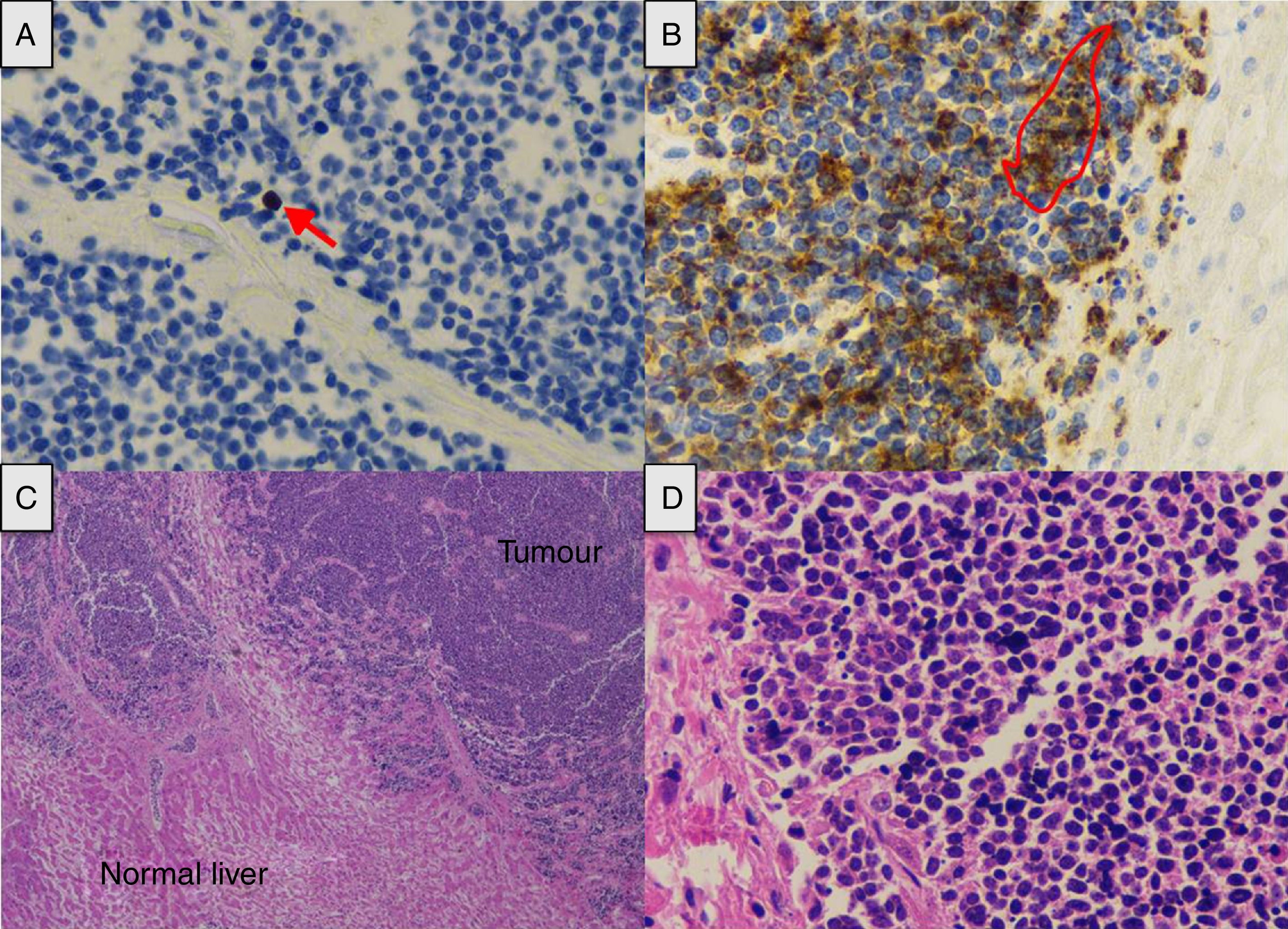

We present the case of a 66-year-old male shepherd, ex-smoker (40pack/years), moderate drinker, who had chronic bronchitis with home CPAP and hypertriglyceridemia. He had a ten-day history of upper respiratory tract infection, with no pyrexia, treated with levofloxacin and prednisone, with abdominal distension, meteorism and oliguria. He did not report the use of drugs of abuse or other hepatotoxic substances. He had no general symptoms, weight loss or family history of liver disease. On admission, a chest-abdomen CT was performed, showing marked hepatomegaly with an anteroposterior axis in the axial section of 30cm and 22cm in the coronal section, no focal lesions identified, with normal biliary tract and large subcarinal mediastinal masses of enlarged lymph nodes (Fig. 1). He was admitted to the internal medicine department initially with the following blood results: blood glucose 104mg/dl, creatinine 1.13mg/dl, urea 67mg/dl, sodium 142mmol/l, potassium 4mmol/l, AST 266U/l, ALT 457U/l, alkaline phosphatase 174U/l, GGT 1033U/l, total bilirubin 2.5mg/dl, amylase 87U/l; normal blood count, coagulation: PT 79%, INR 1.17, derived fibrinogen 550mg/dl; arterial blood gases: pH 7.45, pCO2 35mmHg, pO2 71mmHg, bicarbonate 24.5mM/l and base excess +1.6mM/l. The patient made poor clinical progress, with liver failure (AST 4791U/l, ALT 2301U/l, alkaline phosphatase 286U/l, GGT 739U/l, total bilirubin 12.2mg/dl, LDH 5470U/l, ammonium 106mmol/l, coagulopathy with PT 28% and INR 2.79), acute oliguric renal failure (creatinine 3.8mg/dl, urea 105mg/dl), amylase 165U/l, lipase 185U/l, CK 1866U/l, potassium 7mmol/l, blood glucose 34mg/dl and metabolic acidosis with pH 7, lactate 13mmol/l and base excess −20mM/l. Given his poor progress, he was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU), requiring orotracheal intubation and connection to mechanical ventilation due to acute respiratory failure, haemodynamic instability and neurological deterioration in relation to metabolic encephalopathy. On examination, the patient's abdomen was very distended, tympanic and diffusely painful on palpation. Viral serology for hepatitis A, B, C and E was negative. Cytomegalovirus, syphilis, Epstein–Barr virus and herpes simplex virus were all negative. Serology for Leptospira was negative. Monoclonal antibody CA 72.4 and squamous cell-associated antigen negative. Autoimmunity studies (rheumatoid factor, ANA, AMA, ANCA and anti-smooth muscle) negative. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Leucocytes 19,300 without marked neutrophilia and procalcitonin 4.47ng/ml. The patient suddenly went into distributive shock refractory to the usual supportive treatment including vasopressor drugs, high-dose corticosteroids, continuous renal replacement techniques and empirical treatment with meropenem. He died 12h after being admitted to ICU. A post-mortem examination was carried out and the Pathology report confirmed the proliferation in the liver of chaotically distributed nested tumours which had surrounded and destroyed portal spaces and central veins, widening the sinusoids, trapping the hepatocytes and replacing them with fibrosis (Fig. 2). No masses or obstructions of infra-or suprahepatic vascular structures were identified. Hilum appeared normal. Mediastinal masses of enlarged lymph nodes of tumour-like appearance; subcarinal of 6cm×4cm, bilateral para-tracheal of 8cm×3cm and para-aortic on the anterior side of the arch of 4cm×3cm. There was no compression of venous circulation in this area. Growth of the same type of cells was also observed in the mediastinal and para-aortic lymph nodes. Immunohistochemical study (Fig. 2) was positive for chromogranin, CD56, PGP9.5 and focally with weak intensity for CK7, concluding that it was a WHO grade 2 of 3, large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (2 mitosis/10 high power field [HPF] and Ki-67 of 5%), with massive infiltration of the liver and mediastinal lymphadenopathy, without identifying the primary lesion.

(A) Tumour proliferation index (arrow) (Ki-67×40). (B) The tumour cell expresses chromogranin in its cytoplasm as a marker of neuroendocrine differentiation (contour) (chromogranin×40). (C) Extensive tumour infiltration (haematoxylin-eosin×2). (D) The nuclear distribution of chromatin is similar to that referred to as “salt and pepper” (haematoxylin-eosin×40).

Neuroendocrine tumours are a very heterogeneous group of tumours that produce hormones and can arise in any organ. Within this type of cancer, neuroendocrine carcinomas are poorly differentiated tumours with a high rate of proliferation and very aggressive behaviour that tend to already have metastasis at the time of diagnosis. Some 13% begin with unknown primary tumour9 and the most common location is the gastrointestinal tract. The Ki-67 index classifies them histologically, grade 2 tumours being those with a Ki-67 index of 3–20%. Other indicators of poor prognosis are high levels of chromogranin A (CGA) and the mitotic index.10

We are reminded by this case report that ALF with multiple organ failure due to tumour infiltration is a possibility and, although uncommon, has to be taken into consideration. In our case, neither the medical history nor the imaging tests helped us establish the diagnosis and we were only able to confirm it post-mortem.

To the Pathology Department at Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias and Drs María Aurora Astudillo and Guillermo Eduardo Mendoza.

To the Radiology Department at Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias and Dr Alicia Mesa.

Please cite this article as: de Cima Iglesias S, Viña Soria L, Martín Iglesias L, Astola Hidalgo I, López-Amor L, Escudero Augusto D. Una causa inusual de fallo hepático agudo: infiltración tumoral por carcinoma neuroendocrino. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:320–323.