Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a global public health problem. Until recently, the efficacy of the treatments used was limited, with a sustained viral response (SVR) of less than 50%.

Acute HCV infection is generally asymptomatic. The problem arises with chronic infection (60–80% of cases), which causes progressive liver damage and gives rise to serious complications.

HCV is primarily transmitted parenterally, which is why many HCV patients also have human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

With the advent of direct-acting antivirals (DAA), the success rate has risen to up to 95%. However, there is still a small percentage of patients in whom DAA fail. Our objective was to assess response to DAA retreatment in patients who did not previously respond to these drugs, as well as the causes of this treatment failure.

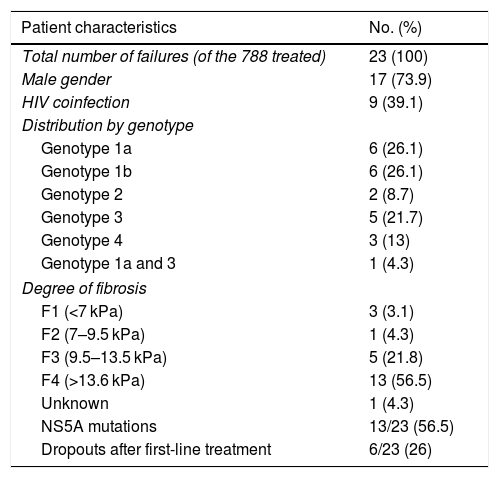

A single-centre retrospective study was performed between January 2012 and April 2018 that analysed 788 HCV patients treated with DAA. Of these, 22 patients (2.79%) with a median age of 57 years and prior DAA treatment failure, were retreated. Table 1 shows the characteristics of this sample. The characteristics of the total sample (gender, fibrosis and genotype) were not collected. The success rate after retreatment was 100%. One patient failed to respond twice and required a third treatment. There were no differences in treatment response between patients coinfected with HIV/HCV and monoinfected patients (Table 2).

Characteristics of the sample.

| Patient characteristics | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Total number of failures (of the 788 treated) | 23 (100) |

| Male gender | 17 (73.9) |

| HIV coinfection | 9 (39.1) |

| Distribution by genotype | |

| Genotype 1a | 6 (26.1) |

| Genotype 1b | 6 (26.1) |

| Genotype 2 | 2 (8.7) |

| Genotype 3 | 5 (21.7) |

| Genotype 4 | 3 (13) |

| Genotype 1a and 3 | 1 (4.3) |

| Degree of fibrosis | |

| F1 (<7 kPa) | 3 (3.1) |

| F2 (7–9.5 kPa) | 1 (4.3) |

| F3 (9.5–13.5 kPa) | 5 (21.8) |

| F4 (>13.6 kPa) | 13 (56.5) |

| Unknown | 1 (4.3) |

| NS5A mutations | 13/23 (56.5) |

| Dropouts after first-line treatment | 6/23 (26) |

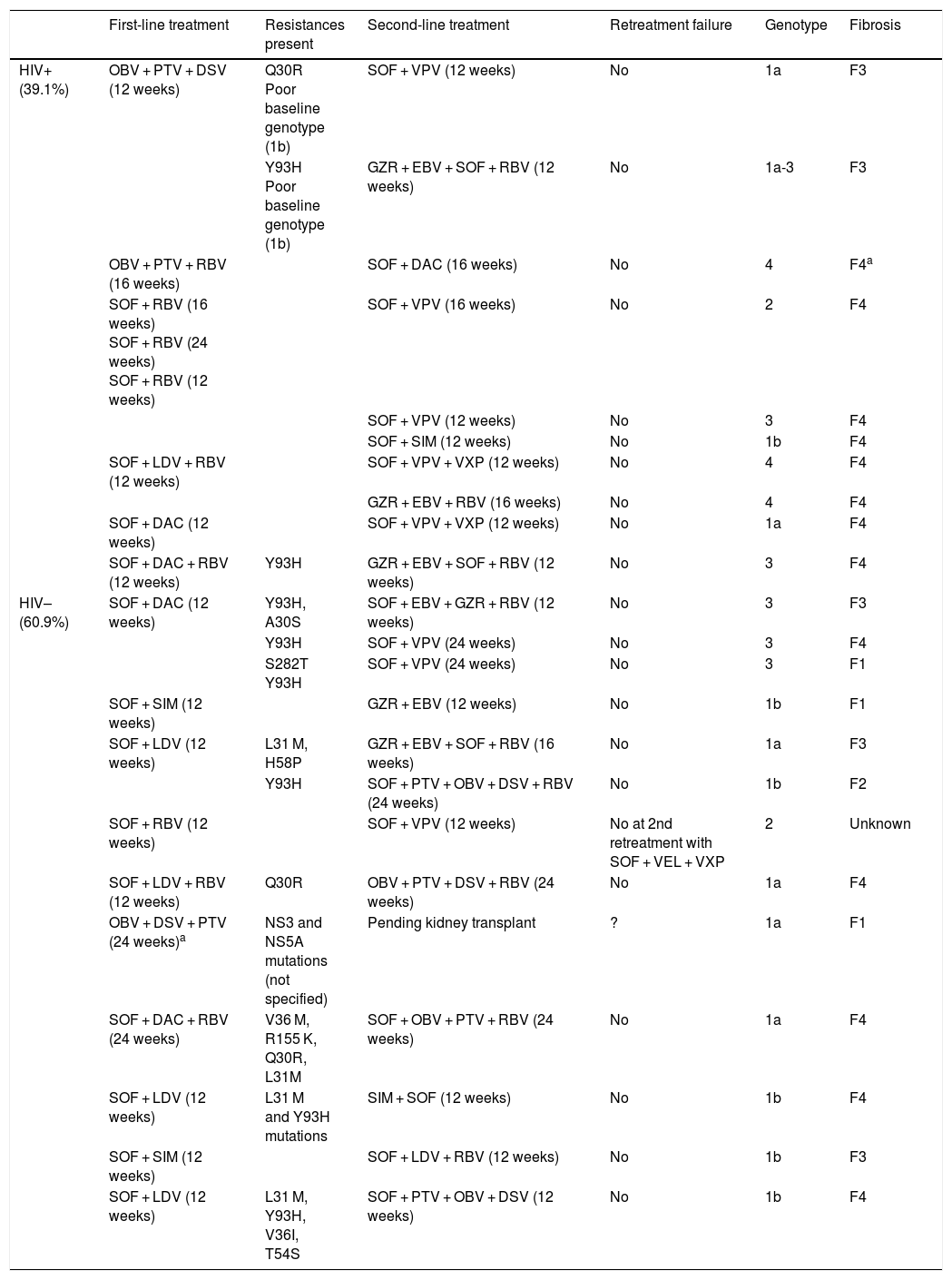

First- and second-line treatment regimen of patients treated with DAA.

| First-line treatment | Resistances present | Second-line treatment | Retreatment failure | Genotype | Fibrosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV+ (39.1%) | OBV + PTV + DSV (12 weeks) | Q30R Poor baseline genotype (1b) | SOF + VPV (12 weeks) | No | 1a | F3 |

| Y93H Poor baseline genotype (1b) | GZR + EBV + SOF + RBV (12 weeks) | No | 1a-3 | F3 | ||

| OBV + PTV + RBV (16 weeks) | SOF + DAC (16 weeks) | No | 4 | F4a | ||

| SOF + RBV (16 weeks) SOF + RBV (24 weeks) SOF + RBV (12 weeks) | SOF + VPV (16 weeks) | No | 2 | F4 | ||

| SOF + VPV (12 weeks) | No | 3 | F4 | |||

| SOF + SIM (12 weeks) | No | 1b | F4 | |||

| SOF + LDV + RBV (12 weeks) | SOF + VPV + VXP (12 weeks) | No | 4 | F4 | ||

| GZR + EBV + RBV (16 weeks) | No | 4 | F4 | |||

| SOF + DAC (12 weeks) | SOF + VPV + VXP (12 weeks) | No | 1a | F4 | ||

| SOF + DAC + RBV (12 weeks) | Y93H | GZR + EBV + SOF + RBV (12 weeks) | No | 3 | F4 | |

| HIV– (60.9%) | SOF + DAC (12 weeks) | Y93H, A30S | SOF + EBV + GZR + RBV (12 weeks) | No | 3 | F3 |

| Y93H | SOF + VPV (24 weeks) | No | 3 | F4 | ||

| S282T Y93H | SOF + VPV (24 weeks) | No | 3 | F1 | ||

| SOF + SIM (12 weeks) | GZR + EBV (12 weeks) | No | 1b | F1 | ||

| SOF + LDV (12 weeks) | L31 M, H58P | GZR + EBV + SOF + RBV (16 weeks) | No | 1a | F3 | |

| Y93H | SOF + PTV + OBV + DSV + RBV (24 weeks) | No | 1b | F2 | ||

| SOF + RBV (12 weeks) | SOF + VPV (12 weeks) | No at 2nd retreatment with SOF + VEL + VXP | 2 | Unknown | ||

| SOF + LDV + RBV (12 weeks) | Q30R | OBV + PTV + DSV + RBV (24 weeks) | No | 1a | F4 | |

| OBV + DSV + PTV (24 weeks)a | NS3 and NS5A mutations (not specified) | Pending kidney transplant | ? | 1a | F1 | |

| SOF + DAC + RBV (24 weeks) | V36 M, R155 K, Q30R, L31M | SOF + OBV + PTV + RBV (24 weeks) | No | 1a | F4 | |

| SOF + LDV (12 weeks) | L31 M and Y93H mutations | SIM + SOF (12 weeks) | No | 1b | F4 | |

| SOF + SIM (12 weeks) | SOF + LDV + RBV (12 weeks) | No | 1b | F3 | ||

| SOF + LDV (12 weeks) | L31 M, Y93H, V36I, T54S | SOF + PTV + OBV + DSV (12 weeks) | No | 1b | F4 |

DSV: dasabuvir; EBV: elbasvir; GZR: grazoprevir; LDV: ledipasvir; OBV: ombitasvir; PTV: paritaprevir; RBV: ribavirin; SIM: simeprevir; SOF: sofosbuvir; VEL: velpatasvir; VXP: voxilaprevir F4.

Our study's success rate is similar to the rate achieved by de Lédinghen et al.1 for retreatment with sofosbuvir (SOF) + grazoprevir/elbasvir + ribavirin for 16–24 weeks in patients with HCV genotypes 1 or 4 in whom first-line DAA treatment failed and who were resistant to NS5A/NS3 inhibitors, who obtained a SVR rate of 100%.

A comparison of the SVR rate between monoinfected and HCV/HIV coinfected patients in our study reveals that, of the 22 patients in whom first-line DAA treatment failed, nine (40.9%) were HIV + and all nine responded (100% success rate in HIV + patients). Of the 13 HIV– patients (59.1%), 13 obtained a SVR (100%). In our series, the response rate in coinfected patients was similar to monoinfected patients, which is consistent with the findings of Berenguer et al.2

Having analysed the possible causes of first-line DAA treatment failure, it can be deduced that resistance to NS5A inhibitors was the primary cause (56.5%). However, unlike the findings published by de Lédinghen et al.,1 our study found that the SVR following the retreatment of patients with NS5A resistance was 100%, meaning that even with the onset of resistance, patients can be retreated with a different NS5A inhibitor. These results are consistent with those published by Halfon et al.3

With regard to the other factors that could have influenced the SVR, the degree of fibrosis (predominantly assessed by elastography and occasionally by liver biopsy) was also not decisive, a fact that has already been reported by Bourliere et al.,4 while patients with genotype 3 were successfully treated in all cases, despite it being considered a difficult genotype to treat.

The characteristics of the only patient in whom DAA treatment failed twice are: male, genotype 2, unknown degree of fibrosis, HIV– and no NS5A amplification. The patient was treated with SOF/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir to achieve a SVR. When patients fail DAA treatment twice, as was the case with our patient, the combination of SOF/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir for 12 weeks is proposed as salvage therapy in all patients without cirrhosis or with compensated cirrhosis, regardless of the type of treatment or genotype (AI).5 The patient who was not retreated is a patient awaiting a kidney transplant due to polycystic kidney disease with F1 fibrosis. This decision was taken by the patient's doctor.

One limitation of our study is the small number of patients retreated, due to the low number of first-line treatment failures.

It can be concluded that the SVR rate following DAA retreatment is very high among patients in whom this treatment previously failed, suggesting that all such patients should be retreated. The causes of treatment failure are consistent with those published in the literature.

FundingThis research did not receive specific financial support from public sector agencies, the commercial sector or non-profit organisations.

Please cite this article as: López Zúñiga MÁ, Prieto Moreno M, de Jesús S, López Ruz MÁ. Respuesta al retratamiento de pacientes virus hepatitis C que han fallado a los antivirales de acción directa. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;42:558–561.