We present the case of a 51-year-old man, a smoker of 60 pack-years with a 20-year history of excessive alcohol consumption (180g of ethanol per day), who had been diagnosed in another centre in 2011 with chronic pancreatitis with development of pancreatic pseudocysts.

He was admitted to the respiratory medicine department in November 2012 for a 7-day history of dyspnoea on moderate exertion and pleuritic pain in the right hemithorax. On examination, he was afebrile, with a cachectic appearance and spider naevi. Auscultation revealed dullness and hypophonesis in the right lung base. The abdomen was soft, palpable and non-painful, with no masses, megalias or findings suggestive of peritonism. Laboratory tests found: glucose 141mg/dL, creatinine 0.69mg/dL, total bilirubin 0.1mg/dL, glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase 12U/L, glutamic pyruvate transaminase 11U/L, gamma-glutamyl transferase 23U/L, alkaline phosphatase 79U/L, amylase 1536U/L, lipase 975U/L, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 170U/L, albumin 3.9g/dL, sodium 143mEq/L, potassium 4.2mEq/L, pro-brain natiuretic protein 76pg/mL, C-reactive protein 12mg/L, haemoglobin 13.2g/dL, haematocrit 41%, platelets 815×103/mm3, leukocytes 12.2×103/mm3 with 9.4×103/mm3 neutrophils, international normalised ratio 0.91, and prothrombin time 118%. Chest X-ray and computed tomography (CT) (Fig. 1) revealed right pleural effusion occupying 45% of the hemithorax and a small left pleural effusion. Abdominal CT (Fig. 2) showed a pancreas with calcifications in the tail, body and uncinate process, with discrete dilatation of the duct of Wirsung related to known chronic pancreatitis. A 3.5-cm hypodense collection was observed in the pancreatic tail–splenic hilum, another 2.6-cm collection in the pancreatic head and another extending from the pancreatic body around the celiac trunk, through the retroperitoneum towards the mediastinum and right pleural space. Diagnostic–therapeutic thoracocentesis was performed, obtaining pleural fluid with pH 7.38, amylase 95,000U/L, glucose 132mg/dL, triglycerides 24mg/dL, proteins 3.8g/dL, LDH 508U/L, and adenosine deaminase 25U/L. Suspecting a pancreatic pseudocyst fistulised to the pleura, the patient was transferred to our department.

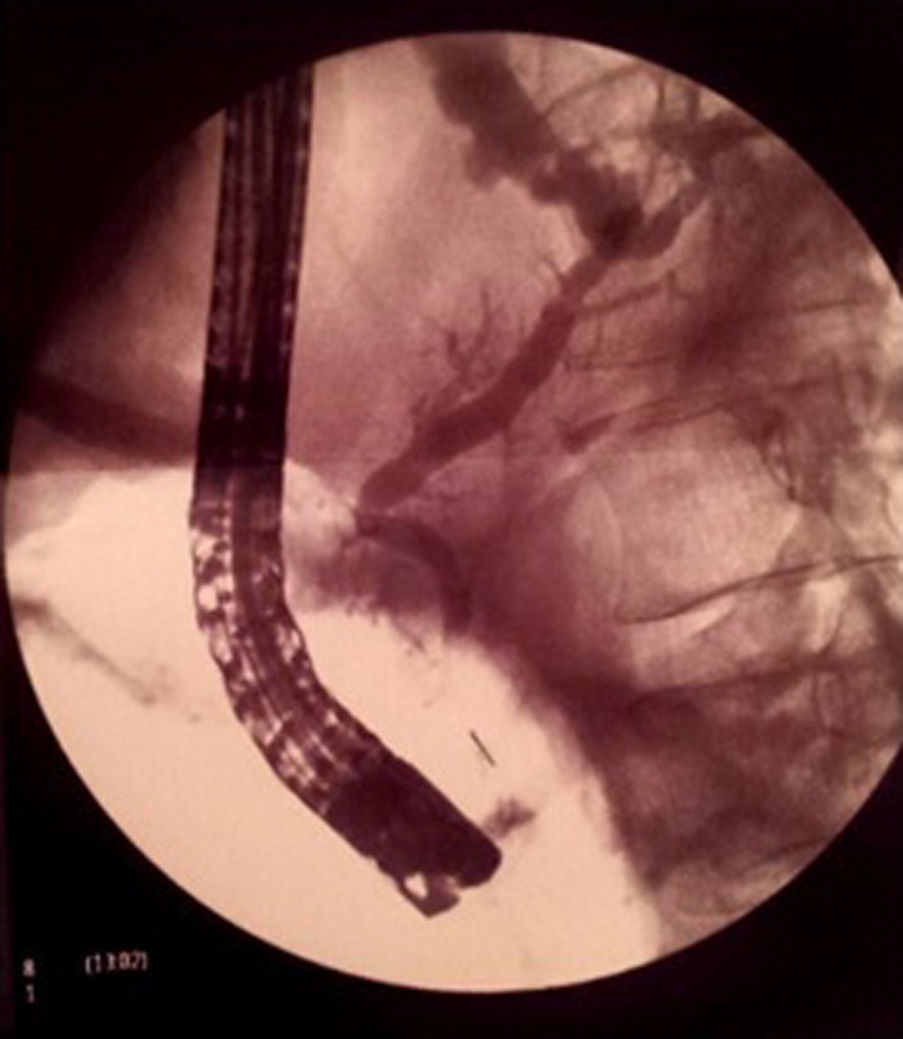

Magnetic resonance cholangio-pancreaticography (MRCP) without secretin was requested for confirmation of the suspected pancreatic fistula, revealing a pseudocyst fistulised to the pleural space by direct contact, but no pancreatic duct disruption. In view of these findings, enteral feeding through a nasojejunal tube was initiated plus octreotide for 3 weeks, requiring repeated therapeutic thoracocenteses for a progressive increase in the right pleural effusion until it almost completely occupied the hemithorax, with contralateral mediastinal shift. Given the patient's gradual clinical–radiological deterioration, the MRCP was repeated. On this occasion, however, pancreatic duct disruption could not be ruled out, so he was referred to a reference centre for diagnostic–therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) (Fig. 3). During the examination, relative cephalic Wirsung duct stenosis was observed, with slight dilatation of the body and tail, and no intraductal calculi. The presence of a fistula at the level of the pancreatic tail was confirmed. Placement of a 15-cm 8.5F plastic stent was uneventful, with good clinical–radiological evolution; the patient has been asymptomatic over the 2 years of follow-up. The stent was exchanged when required, before eventual removal in May 2014.

Pancreaticopleural fistula is a rare complication (<1%) of chronic pancreatitis, predominating in alcoholic pancreatitis,1–5 although up to 50% of patients have no previous history of the condition.4 The incidence described in the literature ranges between 0.4% and 4.5%, with age at diagnosis varying from 20 up to 60 years old.6 Another important aspect to take into account is the patient's chronic smoking, as an independent factor in the development of chronic pancreatitis.7

The main cause is rupture of a pseudocyst into the pleural space and, less commonly, direct leakage from the main pancreatic duct.1,8 The fistula can be anterior or posterior: if it is anterior, it will manifest as ascites, and if posterior, as pleural effusion.2–5 It should be suspected when there is persistent or recurrent pleural effusion in the context of pancreatitis,4 as occurred in our patient. Only 24% of cases present abdominal pain, with symptoms usually lasting 5–6 weeks. The pleural effusion is predominantly left-sided (77%),1,8 and less frequently right-sided (19%) or bilateral (14%). This complication should be suspected in a patient with chronic pancreatitis and concomitant dyspnoea, recurrent cough or pleuritic pain, even if they are asymptomatic from a gastrointestinal point of view.6 There are other causes of increased amylase in pleural fluid; differential diagnosis should be made with neoplasms in the lungs and female genital tract, pneumonia, oesophageal perforation, lymphoma, leukaemia, liver cirrhosis, hydronephrosis and tuberculosis,1,2 which we ruled out in our case by the patient's clinical features, and laboratory and radiological tests. When pleural fluid is seen on imaging techniques (X-ray, CT), diagnostic–therapeutic thoracocentesis is required to confirm the pancreatic origin with amylase >4000U/L and protein >3g/100mL.1,4 The preferred diagnostic technique is MRCP, which can confirm the presence of pancreaticopleural fistula and determine its location. If this is contraindicated or inconclusive, diagnostic–therapeutic ERCP is indicated.

Based on the foregoing findings, treatment was started with enteral nutrition, repeated thoracentesis and octreotide, but the patient did not respond, as occurs in 40–50% of cases described in the literature.2,4 When there is a leak in the head–body (or ductal stenosis) and poor response to/failure of medical treatment, a pancreatic stent is inserted by ERCP that will resolve the pancreatic duct disruption with no complications, as happened in our case.3,9 This reduces the ductal pressure, aiding drainage of secretions by a physiological route and facilitating duct healing.2 In some situations, such as complete rupture or obstruction of the duct, or a fistula originating in the distal segment of the pancreatic duct,6 as in our case, stent placement is limited, and for this reason the patient was referred to a reference centre.

When medical-endoscopic treatment fails, or the duct is completely obstructed, surgical treatment—which has a mortality rate of between 3% and 5%—should be considered.8

In conclusion, a pancreaticopleural fistula should be suspected in a patient with dyspnoea, chest pain or recurrent cough, especially those with chronic pancreatitis. Diagnostic–therapeutic thoracocentesis is required to confirm the diagnosis, verifying a pancreatic origin with amylase levels >4000U/L and proteins >3g/100mL. The treatment of choice is medical with octreotide or somatostatin. If this fails, or if the fistula is located in the tail, the first option is surgery. However, in the absence of stenosis and intraductal calculi, treatment by ERCP can be considered in reference centres (as in our case), since this has a lower morbidity and mortality rate than surgery.10

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Please cite this article as: Sánchez A, Ramírez de la Piscina P, Duca IM, Estrada S, Salvador M, Campos A, et al. Derrame pleural de predominio derecho secundario a fístula pancreatopleural en paciente con pancreatitis crónica asintomática. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:529–531.