Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS) is an exceptional disorder in paediatric and adolescent patients. It is often confused with other conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), delaying its diagnosis for years after the first consultation. We describe the case of a teenager with symptoms of tenesmus and rectal bleeding initially classified as ulcerative proctitis but who was later, in view of refractoriness to treatment, diagnosed with SRUS.

The patient was a 15-year-old boy with a history of bronchial asthma and a 1-year history of diarrhoea with up to 7 small-volume stools daily with mucus and haematochezia associated with colicky abdominal pain. Laboratory tests were normal. Colonoscopy revealed an erythematous inflamed erosive ring in the rectum with undamaged distal rectal mucosa and rest of the colonic mucosa normal; histological study reported non-specific chronic rectitis. With a presumed diagnosis of ulcerative proctitis, he initiated treatment with topical mesalazine and was referred to the IBD clinic for follow-up.

The patient was shy and withdrawn and reluctant to provide any information, so his mother described the symptoms. Due to the persistence of symptoms despite the treatment initially described, he was treated with a combination of both topical mesalazine with topical budesonide, and topical mesalazine with oral mesalazine, also with no response. Oral corticosteroids were also tried, similarly with no improvement observed.

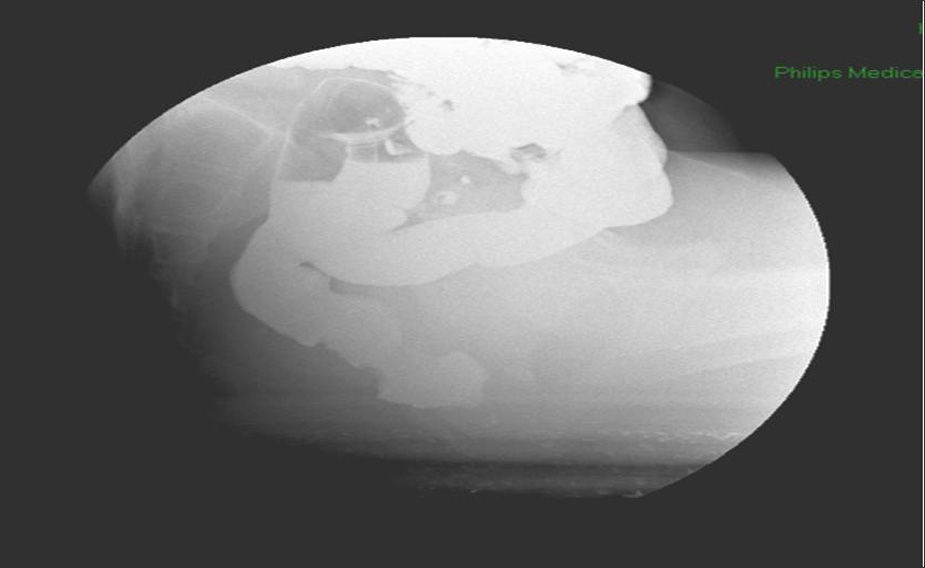

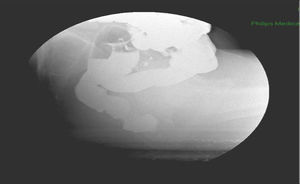

At that time, in view of the refractoriness to treatment and the non-typical appearance of the ulcerative proctitis in the initial colonoscopy, we reconsidered the diagnosis and decided to repeat the endoscopic and histological study, observing persistence of a circumferential ring around 7–8cm from the anal margin, polypoid, erosive and friable, but not affecting the distal rectal mucosa (Fig. 1). Biopsies reported benign border and base of the ulcer with development of granulation tissue, regenerative epithelial changes, and fibromuscular proliferation in the lamina propria, with no changes indicative of IBD, suggesting the possibility of a lesion associated with prolapse. After re-questioning the patient about the symptoms, with the aforementioned difficulties, the symptoms were more suggestive of tenesmus and defaecation urgency with small-volume stools and incomplete evacuation, all associated with colicky abdominal pain that improved after defaecation, suggesting the possibility of an alteration in rectal defaecation dynamics that in turn led to the onset of SRUS. Video defecography was performed, observing recto-rectal intussusception during defaecation with no anal prolapse (Fig. 2). Anorectal manometry found slight hypotony of the anal sphincter, slight loss of strength in the sphincter muscles and early defaecation urgency with normal expulsion test.

Plantago ovata was prescribed and biofeedback initiated, with a good clinical response to date.

The first clinical and histopathological description of solitary rectal ulcer, a benign chronic disease, dates from 1969.1 It is a rare entity with an incidence of 1/100000 population/year, more common in young adults aged between 20 and 35 years, especially in females.2 Presentation in childhood or adolescence is exceptional, with only isolated case series having been reported.3–6

Clinically, it manifests with rectal bleeding, which is usually mild, often accompanied by mucus, as well as tenesmus, straining, feeling of incomplete evacuation, abdominal pain, proctalgia and, occasionally, defaecation urgency.2–6 There may be some degree of rectal prolapse or internal rectal intussusception accompanied by a feeling of obstruction, although external rectal prolapse has rarely been observed.6 It has been described as a basic disorder of defaecation dynamics with prolapse of the rectal mucosa through the contracting puborectalis muscle, due to the increased intra-abdominal pressure with consequent strangulation of the rectal mucosa leading to ischaemia, congestion, oedema and ulceration of the mucosa.7 Another aetiopathogenic possibility is direct trauma as a result of attempts to digitally remove hard stools from the rectum.

Rectoscopy with biopsies is essential for diagnosis. The typical finding is a superficial ulcerated lesion of variable morphology (round, oval, linear or serpiginous) surrounded by an erythematous halo and located in the anterior or antero-lateral wall of the rectum. However, the lesion is not always solitary–it can be multiple or circumferential as in our case–nor ulcerated, with hyperaemic or polypoid lesions also having been described.8 It can therefore be confused, as in our patient, with other more common entities such as IBD, infectious rectitis, lesions due to sexual abuse or even rectal cancer, with the consequent delay in diagnosis.

The histological findings are characteristic: thickening of the mucosa, elongation and distortion of the glands, oedematous lamina propria with a large amount of collagen and variable proliferation of fibroblasts, and thickening of the muscularis mucosae, with muscle fibres that ascend vertically.1

Anorectal manometry and video defecography are useful for assessing the integrity of the rectal sphincters and the physiological state of the anus and rectum, although their diagnostic role is limited.9

Treatment of SRUS is problematic, and there are no consensual therapeutic recommendations. It is advisable to reassure the patient and their family that the condition is benign. There are 4 basic pillars of treatment: hygiene-dietary measures, pharmacological treatment, biofeedback and surgery. The response to increasing the intake of dietary fibre combined with bulk-forming laxatives is variable, and patients with associated rectal prolapse are least likely to benefit from these measures. Various topical drugs, such as sucralfate, aminosalicylates and corticosteroids, have been empirically tested with varied results.6,10 The encouraging results obtained with behavioural therapies in constipation have prompted clinicians to use biofeedback techniques in the treatment of SRUS.11 One third of patients, especially those who present rectal prolapse, do not respond to the measures described above, and present disabling symptoms that will require surgical treatment, which usually consists of resection of the thickened mucosa and rectopexy.12

In short, SRUS is a rare entity, particularly in paediatric and adolescent patients, with a chronic, benign course and which requires a high index of suspicion for early diagnosis.

Please cite this article as: Hernández Martínez A, Lázaro Sáez M, San Juan López C, Suárez Crespo JF. Úlcera rectal solitaria en paciente adolescente. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:665–667.