Simultaneous pancreas–kidney transplantation (PKT) is the treatment of choice for patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus and end-stage renal disease. Gastrointestinal bleeding is an uncommon complication following pancreas–kidney transplantation (around 1%), but it is associated with high morbidity and mortality. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding related to gastric ulcers is more frequent than lower bleeding. The rupture of a pseudo-aneurysm of the graft, from splenic or gastro-duodenal artery, is a rare cause of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding in this group of patients.1

Investigation of gastrointestinal bleeding in a pancreas–kidney transplant recipient includes initially an upper and/or lower endoscopy, followed for radiologic procedures as an abdominal computed tomography (CT) and a digital subtraction angiography (DSA).

Small bowel Capsule Endoscopy (SBCE) is an endoscopic tool for visualize small bowel and with a higher diagnostic yield in obscure gastrointestinal bleeding compared to radiologic procedures.2,3

This is a case of a patient with previous simultaneous pancreas–kidney transplantation who presented an obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Capsule endoscopy played an important role in the diagnosis and management.

A 53-year-old man underwent kidney–pancreas transplantation for type I diabetes mellitus and end-stage renal disease. After two years, he was admitted to the emergency room with 4 days of melena, without instability. Nasogastric lavage showed clear gastric content, with no blood. Hemoglobin level was 8.4g/dl with normal platelet count and coagulation parameters. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed showing a small sessile polyp lesion in antrum with no traces of blood.

After 24h, the patient had a rebleeding episode and 4 blood units were transfused. After clinical stabilization colonoscopy was performed showing diverticulosis in the sigmoid colon and abundant blood traces. CT angiography (CTA) was performed showing a 2.3cm pseudo-aneurysm at the anastomosis between the graft's pancreatic arteries and the recipient's common iliac arteries. There was no contrast extravasation into the intestinal lumen.

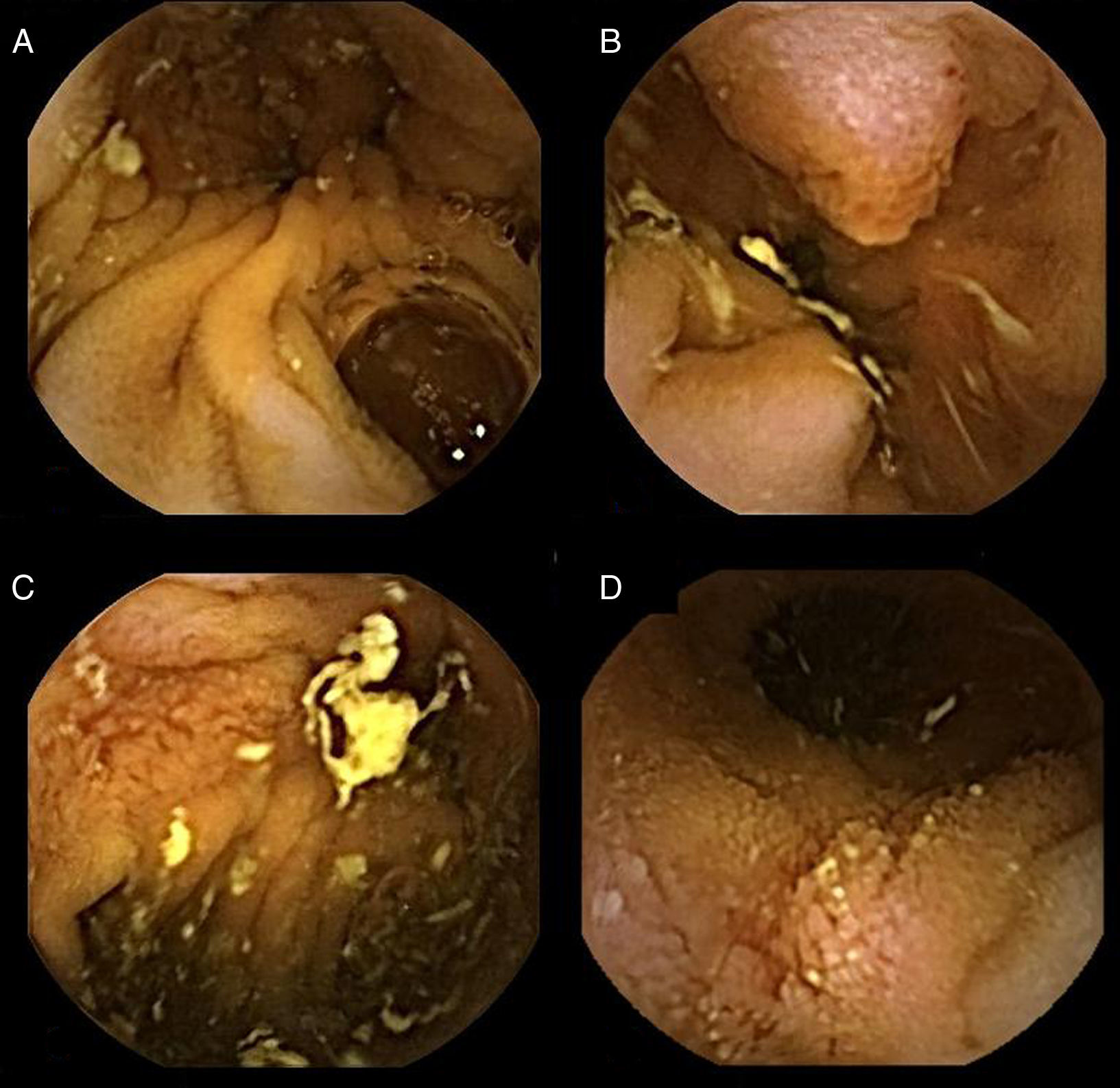

A Pillcam Small Bowel Capsule Endoscopy (SB2, Given Imaging, YoKneam, Israel) was administered, showing as the most important finding, a cavity located in medium jejunum (40min after pylorus) where the capsule was retained for more than 3h surrounded by several ulcerative lesions, mucosal erythema and neovascularization as well as a polypoid image that seemed to correspond to ampulla of Vater (Fig. 1). These findings suggested that the pseudo-aneurysm was fissuring the small bowel, so an urgent angiography was performed.

The angiography of the right common iliac artery confirmed a pseudo-aneurysm originated in the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) anastomosis (Fig. 2). Embolization of the aneurysmal sac was performed. First, two coils were placed in a branch of the SMA to prevent retrograde filling of the pseudo-aneurysm and later, detachable coils were used to treat the aneurysmal sac. The final angiography showed an 80% exclusion of the pseudo-aneurysm. Subsequent Doppler ultrasound and CTA confirmed its complete occlusion. Additionally, a micotic aneurysm was ruled out after a labeled leukocyte scintigraphy.

The patient presented an excellent outcome, with no recurrent bleeding episodes, and was discharged in a week. After 1 year of follow-up the patient has not presented any rebleeding episode, Doppler ultrasound remains without changes, and the pancreas and kidney transplant continue to function properly.

This is a rare case of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding due to a donor pancreatic artery pseudo-aneurysm, complicated with an arterioenteric fistula.

There are few cases reported in the medical literature.4–7

The pseudo-aneurysms are serious, usually late-onset complications, which could be located at any intraparenchymal artery of the graft, at the interposed arterial graft or at the donor-recipient anastomosis and may debut as arterio-enteric fistula (duodenum-enteric bypass).

Clinical presentation is usually as a lower gastrointestinal bleeding (enteric bypass), right lower quadrant pain, pulsate mass, sepsis (infectious ethology) and hemodynamic instability in case of rupture.

The diagnosis is usually made by Doppler ultrasound, CTA, MRA or DSA. The endovascular approach is becoming the treatment of choice due to the high risk of graft loss associated with open surgical correction. If the patient is stable and the origin of the aneurysm is not infectious it can be treated by angiographic embolization. In cases of hemodynamic instability (ruptured risk or recent rupture) or when embolization is not feasible, surgical treatment (transplantectomy) should be considered.8–11

In this case, a small pseudo-aneurysm was diagnosed previously by CT examination but wall contact was not demonstrated initially and bleeding was not suspected. SBCE showed the presence of ulcers at this level and an arteria-enteric fissure of the donor artery pseudo-aneurysm was suspected. So we must highlight the superiority of the capsule to visualize lesions like ulcers that go unnoticed by the radiology.

In conclusion, gastrointestinal bleeding due to a donor artery pseudo-aneurysm with arterio-enteric fistula is a severe complication in kidney–pancreas transplanted recipients, and although Doppler ultrasound, CTA, MRA angiography and arteriography are the main diagnostic studies, capsule endoscopy could play a role in selected cases if radiology studies are normal.