Pseudocirrhosis is a radiological term that refers to a condition showing changes in hepatic contour that mimic cirrhosis in the absence of the typical histopathological findings of cirrhosis in pathology tests.1 This entity has been described primarily in cases of metastatic breast cancer with or without use of systemic chemotherapy (CT). However, similar cases have been observed in other malignancies, such as pancreatic, oesophageal and thyroid cancer.2–5 Its prevalence and the exact mechanisms underlying its onset are still unknown. According to the studies published to date, it has been suggested that the morphological changes may be secondary to both the effect of metastatic infiltration of healthy tissue and the hepatotoxicity of CT.6

This article presents the case of a 39-year-old female patient who was admitted to the digestive diseases department in August 2015 with abnormal liver function test results and evidence of diffuse parenchymal liver disease on her abdominal CT scan.

Her personal medical history included a mastectomy with right lymph node dissection due to pT1b(m) pN1a invasive ductal carcinoma (ER−, PR, HER2+++, p53 [80%], Ki-67 [30%], BRCA−) in June 2012. She received adjuvant CT with 4 cycles of cyclophosphamide+doxorubicin followed by combined therapy with docetaxel+trastuzumab for 3 months until March 2013. She then continued on trastuzumab monotherapy until she had completed one year of therapy, finishing chemotherapy in January 2014 and having a prophylactic left mastectomy in June 2014. The patient remained asymptomatic and with normal blood test results for 26 months of follow-up, and had a chest-abdominal CT scan in May 2014, which was completely normal.

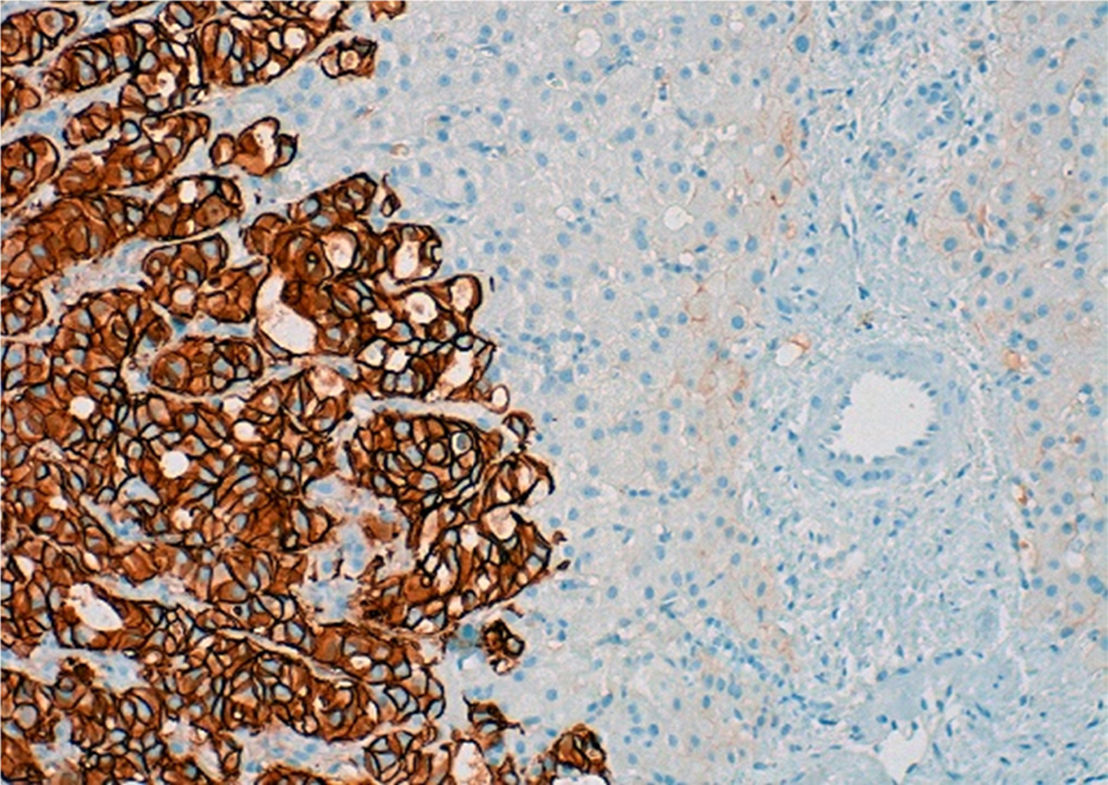

On admission, the patient had been suffering from asthaenia and jaundice for 3 months with no other associated symptoms. She said she did not take drugs or toxic substances. Her physical examination was normal, and blood tests showed she had hypertransaminasaemia with indirect hyperbilirubinaemia and EBV, CMV, HBV, HAV and HCV tests were negative. The CT scan (Fig. 1) performed one month prior to admission showed diffuse parenchymal liver disease, predominantly in the left lobe of the liver, with a heterogeneous pattern of signal intensity; there were no SOL of the liver or signs of metastasis, suggesting veno-occlusive disease of the liver. During her admission, her liver function deteriorated (Child–Pugh B7 and MELD 16) and she had progressive thrombocytopaenia, with low levels of antinuclear antibodies (ANA); the rest of the autoimmune study was negative.

CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast dye on 30/07/2015: diffuse parenchymal liver disease, predominantly in the left lobe of the liver, with a heterogeneous mosaic pattern of signal intensity with permeable hepatic veins. It also shows areas of capsular retraction and changes in hepatic contour.

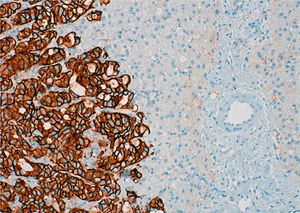

An MRI scan of the liver showed a regenerative liver with extensive areas of fibrosis and signs of portal hypertension, with no evidence of lesions indicative of malignancy. Hepatic vein involvement was ruled out using Doppler ultrasound and an endoscopy revealed grade III/IV oesophageal varices and moderate portal hypertensive gastropathy (PHG). Finally, given her blood clotting disorder, it was decided to perform an ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy of the liver, obtaining 2 fragmented thin cylinders of liver tissue with a retained architectural pattern. Microscopic examination showed poorly defined areas of fibrosis with nests of tumour cells and vascular invasion of the sinusoids and some portal veins, explaining the mechanism of portal hypertension (presinusoidal and sinusoidal). However, there were no signs of veno-occlusive disease since the central veins were not affected, and no nodular regenerative hyperplasia (NRH) nodules were found either. Immunohistochemistry showed positive nuclear staining for GATA-3, which is characteristic of, but not specific to, the mammary tissue. Infiltrating cells were also HER2+++ (Fig. 2) with negative staining for ER and PR (similar behaviour to primary breast tumours). Therefore, the findings confirmed the presence of liver metastases from breast carcinoma more than 2 years after diagnosis, despite performing a mastectomy, 2 cycles of adjuvant CT and one year of biological treatment. Over the course of 2 months, the patient's clinical condition, blood test results and imaging deteriorated, resulting finally in her death.

Pseudocirrhosis with hepatic metastasis may be associated with retraction of Glisson's capsule over liver metastases as a result of CT, mimicking macronodular cirrhosis.7 It is independent of the presence and/or size of hepatic metastases and is secondary to CT agents. Toxicity causes parenchymal ischaemia with secondary transformation into NRH in the absence of the characteristic fibrous bridges present in cirrhosis. Pathophysiologically, NRH may cause portal hypertension due to compression of the sinusoids and central veins, in a similar way to veno-occlusive disease. Very few articles have been published in the literature on cases of pseudocirrhosis in the absence of CT. To explain this phenomenon, a desmoplastic reaction in the form of extensive fibrosis secondary to infiltration of atypical metastatic cells has been put forward as the possible mechanism of such pseudocirrhosis.6

The patient may be asymptomatic and only have abnormal blood test results. Once the disease progresses, typical signs of decompensated cirrhosis of the liver may be observed. Radiological findings are typical of cirrhosis, including irregularity of the liver contour, multifocal capsular retraction, decreased volume of the right lobe, hypertrophy of the caudate lobe and left lobe, possibly accompanied by signs of portal hypertension. It may be helpful to compare images of the pseudocirrhotic liver with earlier scans showing an anatomically normal liver. Morphological changes usually develop over a very short period of time, ranging from weeks to a few months after starting CT, progressing more quickly than cirrhosis. The only way to distinguish real cirrhosis from pseudocirrhosis is a liver biopsy. However, this is an invasive method that cannot always be performed. Therefore, a good medical history is essential to link radiological findings to the patient's personal history.

Please cite this article as: Hidalgo-Blanco A, Aguirresarobe-Gil de San Vicente M, Aresti S, de Miguel E, Cabriada-Nuno JL. Seudocirrosis en cáncer de mama metastásico. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:111–113.