There is currently a therapeutic arsenal to avoid colectomy in patients with moderate or severe ulcerative colitis (UC). Tacrolimus, an orally administered calcineurin inhibitor, is an effective option for inducing remission in severe UC.1 The efficacy of tacrolimus combined with vedolizumab has been demonstrated in partial response or secondary loss of response.

Ustekinumab (UST) is a drug that blocks the p40 subunit of interleukin 12/23 approved to treat moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis2 with an adequate safety profile.

We present the case of a 62-year-old man, diagnosed with long-standing, extensive, corticosteroid-dependent UC. Several treatments had previously failed: azathioprine, infliximab and apheresis. Adalimumab was effective in maintaining remission for six years, but there was a secondary loss of response that did not improve after intensification. No primary response to vedolizumab.

In 2019, the patient started treatment with tofacitinib, achieving early clinical remission free of corticosteroids for two years, and a significant decrease in faecal calprotectin (FC).

In January 2021, he suffered from COVID pneumonia and was admitted to the intensive care unit, requiring mechanical ventilation for two months. He made a full recovery, but developed a pulmonary thromboembolism.

Four months later, the UC worsened with an increase in the number of bloody stools and abdominal pain. The partial Mayo score was 7 points; haemoglobin, albumin and C-reactive protein values were normal, but FC was 1977 mg/kg. Endoscopic activity was Mayo 2 in the rectum and left colon.

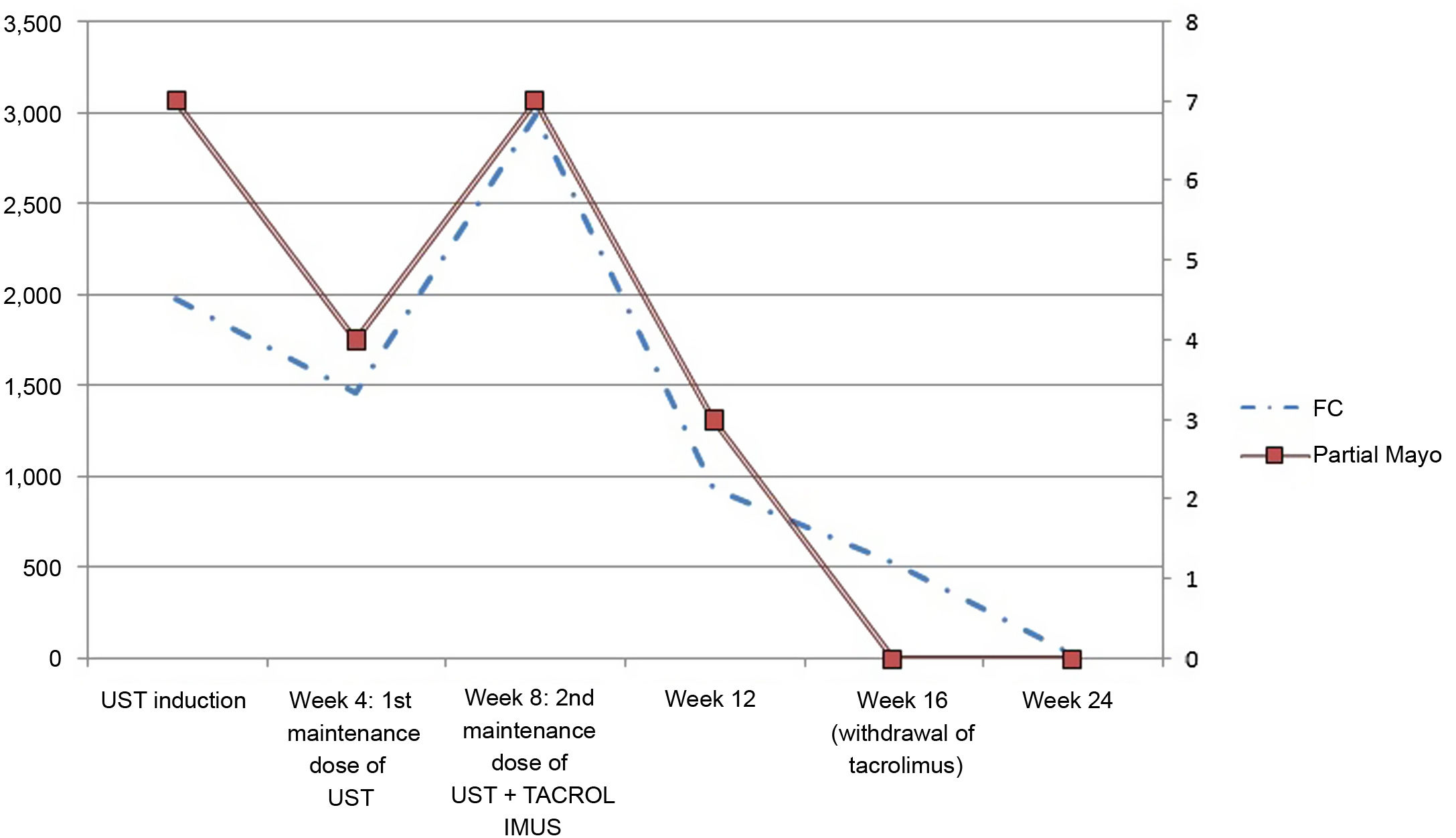

The patient was given the induction dose of 520 mg intravenous UST and oral prednisone (60 mg daily); corticosteroids were gradually reduced. Four weeks later, 90 mg subcutaneous UST was administered trying to optimise maintenance treatment, then 130 mg/intravenous/every four weeks, but there was no response. FC increased to 2983 mg/kg (Fig. 1).

At that time, oral tacrolimus was started at a dose of 0.15 mg/kg daily and adjusted according to trough levels of 10−155 ng/ml.

Eight weeks later, the patient achieved clinical remission (partial Mayo score 0) and tacrolimus was withdrawn. The patient is currently stable on UST 130 mg intravenously/every four weeks; FC progressively decreased to <27 mg/kg. He has not developed adverse effects.

Tacrolimus is a safe and effective drug to induce remission in severe UC; combined with UST, it can be an alternative in refractory UC.

To date, there is no evidence of these two drugs being used in combination in UC.

Two clinical cases have recently been published about the combination of cyclosporine and UST being used to induce remission in UC.3

A French multicentre study4 evaluated the efficacy and safety of cyclosporine in combination with vedolizumab in corticosteroid-refractory UC and with previous exposure to anti-TNF therapy. This combination prevented colectomy in two-thirds of patients after one year. Similarly, in the largest cohort of patients with severe corticosteroid-refractory UC induced with calcineurin inhibitors as a bridge to vedolizumab maintenance, reported by Ollech et al. in Canada, it prevented colectomy in 67% of cases after 12 months.5

In our patient, after a history of COVID-19 with pulmonary thromboembolism, UST was chosen due to the potential thrombotic risk of tofacitinib.

Ustekinumab is a safe therapeutic alternative in UC and Crohn's disease. Despite early optimisation of UST, there was no response, but using it in combination with tacrolimus made it possible to achieve clinical remission free of corticosteroids and normalisation of FC.

Tacrolimus may be an alternative to induce remission in combination with UST in refractory UC when the response is slow. More studies are needed to demonstrate the synergy of this combination.