Tailgut cysts are rare congenital tumours of the presacral space. The accepted origin is a developmental abnormality arising during the embryonic phase, developing from remnants of the primitive gut due to incorrect involution of the appendix or tail at the distal end of the caudal portion of the gut (tailgut).1

This study looks at a series of 4 cases of tailgut cysts that have been surgically removed at our centre.

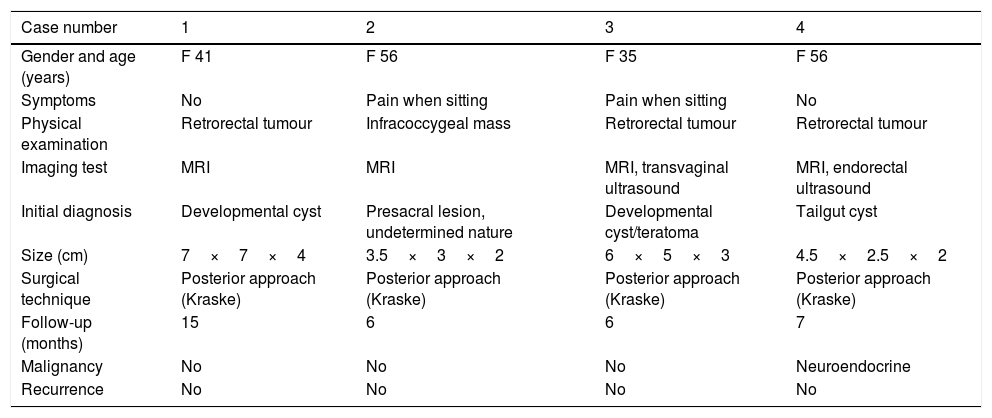

The clinical and pathological characteristics of these tailgut cysts are summarised in Table 1.

Clinical data for cases of tailgut cysts.

| Case number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender and age (years) | F 41 | F 56 | F 35 | F 56 |

| Symptoms | No | Pain when sitting | Pain when sitting | No |

| Physical examination | Retrorectal tumour | Infracoccygeal mass | Retrorectal tumour | Retrorectal tumour |

| Imaging test | MRI | MRI | MRI, transvaginal ultrasound | MRI, endorectal ultrasound |

| Initial diagnosis | Developmental cyst | Presacral lesion, undetermined nature | Developmental cyst/teratoma | Tailgut cyst |

| Size (cm) | 7×7×4 | 3.5×3×2 | 6×5×3 | 4.5×2.5×2 |

| Surgical technique | Posterior approach (Kraske) | Posterior approach (Kraske) | Posterior approach (Kraske) | Posterior approach (Kraske) |

| Follow-up (months) | 15 | 6 | 6 | 7 |

| Malignancy | No | No | No | Neuroendocrine |

| Recurrence | No | No | No | No |

F: female; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

All patients were female, with a mean age of 47 years. The mean size of the lesions was 5.2cm.

Two of the 4 patients had no local symptoms attributable to the lesion when first evaluated; one of these patients was referred after finding the lesion during a gynaecological check-up, and the other was being treated for an anal fistula. The other 2 patients reported experiencing pain for several months when sitting. In 3 of the cases, the rectal examination detected a well-defined, mobile retrorectal mass, while the other case had a soft, palpable, infracoccygeal mass.

All patients underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which showed lesions with well-defined borders, compression of the local rectal wall and no infiltration. The lesions were heterogeneous in appearance with multiple cystic components, showing areas of hypointensity or hyperintensity on T1-weighted sequences and hyperintense areas on T2-weighted sequences; only one lesion had a more complex morphology, with areas with solid and cystic components (partial hyperintensity on T1 and extreme hyperintensity on T2). In this case, an endorectal ultrasound was performed, with similar findings.

All patients were operated on by the same surgeon using a posterior approach with transsacral resection (Kraske technique); 3 patients also had a partial coccygectomy while 1 had a complete coccygectomy, with additional removal of the last sacral vertebra. Resection was always macroscopically complete, with no intraoperative injury to muscle fibres of the anal sphincter or significant blood loss. Primary closure was performed on all patients, and biological mesh was used in 2 cases, which was sutured to the levator ani muscle.

Histological examination revealed that the lesions had multiple cystic components; different subtypes were identified in the epithelium, along with sub-acute or chronic inflammatory changes in some samples. A solid component (coinciding with the complex solid-cystic lesion observed previously on MR images) was detected in one case, with the incidental finding of a neuroendocrine tumour (NET) measuring 1.5cm, with Ki-67 labelling index of less than 2%; it was classified as grade 1.

The mean length of hospital stay was 4 days, with a mean follow-up of 8.5 months. No complications were detected during the immediate post-operative period or during the follow-up period, and there were no reports of disease recurrence.

Middledorpf first described a congenital presacral cyst in 1885,2 but it was not until 1988 that Hjermstad and Helwig speculated that they originate from remnants of the primitive gut, providing the largest case series to date, with 53 cases.1 More than 200 cases of tailgut cysts have been recorded in international literature. Most publications mention isolated cases, but some series are larger and from reference centres (Table 2).

Main published series that include tailgut cysts.

| Series | Year | n | Mean age (years) | F | Technique | F/U (months) | Recurrence | Malignancy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Johnson AR et al. | 1986 | 5 | 32 | 4 | U | U | U | 0 |

| Hjermstad BM et al. | 1988 | 53 | 35 | 41 | Posterior approach (22) | 10 | 4 | 1 |

| Transanal (9) | ||||||||

| Abdominoperineal resection (1) | ||||||||

| Unknown (21) | ||||||||

| Hannon J et al. | 1994 | 4 | 37.8 | 4 | Transsacral (2) | 36 | 1 | 0 |

| Combined abdominosacral (2) | ||||||||

| Prasad AR et al. | 2000 | 5 | 50.4 | 4 | U | U | U | 2 |

| Singer MA et al. | 2003 | 4 | 42.5 | 3 | Parasacrococcygeal | U | U | 0 |

| Lev-Chelouche D et al. | 2003 | 12 | 37 | 12 | Posterior approach (9) | 54 | 0 | 0 |

| Anterior approach (3) | ||||||||

| Yang DM et al. | 2005 | 5 | 43.6 | 5 | U | U | U | 0 |

| Buchs N et al. | 2007 | 10 | 38.4 | 10 | Transperineal (6) | 60 | 1 | 0 |

| Parasacrococcygeal (4) | ||||||||

| Aflalo-Hazan V et al. | 2008 | 11 | 40.8 | 8 | Posterior approach (8) | U | U | 1 |

| Combined abdominosacral (2) | ||||||||

| Abdominoperineal resection (1) | ||||||||

| Woodfield JC et al. | 2008 | 8 | 30 | 8 | U | U | 1 | 0 |

| Grandjean JP et al. | 2008 | 16 | U | U | Posterior approach | U | 1 | 0 |

| Mathis KL et al. | 2010 | 31 | 52 | 28 | Posterior approach (20) | U | 1 | 4 |

| Anterior approach (9) | ||||||||

| Combined abdominosacral (2) | ||||||||

| Baek SW et al. | 2011 | 8 | 40.4 | 8 | Posterior approach | 18 | 1 | 0 |

| Rosa G et al. | 2012 | 5 | 32 | 5 | Transperineal (3) | 140 | 3 | 0 |

| Transanorectal (2) | ||||||||

| Chéreau N et al. | 2013 | 28 | U | U | U | U | U | 6 |

| Patsouras D et al. | 2015 | 17 | 35 | 15 | Posterior approach (16) | 13 | 1 | 1 |

| Combined abdominosacral (1) |

U: unknown; F: female; F/U: mean follow-up.

Tailgut cysts are most common in middle-aged women, with a variable clinical presentation, and such cysts are diagnosed incidentally in 50% of cases.1,3 In the event of a superinfection, symptoms of drainage or swelling compatible with anal fistula may appear, which is a common cause of initial delays in diagnosis. Physical examination usually reveals a well-defined retrorectal tumour that is compressing and displacing the posterior rectal wall without infiltrating it.4

It is important to perform an accurate differential diagnosis of all masses of the presacral space (including developmental cysts, teratomas, sacral chordomas, neural tube defects or neurogenic tumours) in order to prevent a higher rate of recurrence (up to 60% in some series) or other complications.1,4

The use of endorectal ultrasound may be useful for characterising involvement of the rectal wall, although the current trend is to perform more cost-effective imaging tests, primarily MRI.5 Pre-operative biopsy is not currently recommended due to the possibility of local tumour spread; it also has no significant diagnostic value.6

The treatment of choice for tailgut cysts is complete surgical excision with tumour-free margins, which is essential for a good outcome, especially in the event of possible superinfection or malignant transformation.1,3 The chosen approach must be safe and effective. The posterior or transperineal approach is recommended in the case of accessible masses that do not extend beyond the third sacral vertebra, while bulky tumours in an anterior position or higher will require an abdominal or combined approach.7 The Kraske technique allows good visualisation of the rectal wall and preservation of sphincter function, with low associated morbidity and mortality rates.4,7

The risk of malignant transformation reported is around 7%,1,3 but may even reach up to 40%.6 Tailgut cysts have been observed to transform into adenocarcinomas and NETs, which have a highly favourable prognosis compared to other malignancies. The presence of NET is unusual, and has been described in only 20 cases to date.8 It is suggested that these tumours are possibly associated with hormones and oestrogen receptors as the potential therapeutic target, which is yet to be studied.9

Please cite this article as: Mora-Guzmán I, Casado APA, Rodríguez Sánchez A, Bermejo Marcos E. Hamartoma quístico retrorrectal: presentación de 4 casos. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:103–105.

Part of this study was presented at the XX National Meeting of the Fundación Asociación Española de Coloproctología (Spanish Association of Coloproctology), Elche, May 2016.