Ultra-short coeliac disease (USCD) is a novel celiac disease (CD) subtype limited to the duodenal bulb (D1). HLA haplotypes and flow cytometry have not been assessed yet.

AimsTo compare genetic, clinical, serologic, histopathologic and inmmunophenotypic parameters between USCD and conventional celiac disease (CCD) patients.

MethodsProspective single-center study in children and adult patients undergoing duodenal biopsies on a gluten-containing diet. Biopsies for histology and flow cytometry were taken separately from D1 and distal duodenum. Biopsies in seronegative patients with celiac lymphogram were repeated after 2 years on a gluten-free diet.

ResultsAmong 505 included patients, 127 were diagnosed with CD, of whom 7 (5.5%) showed USCD. HLADQ2 was significantly less common in USCD compared to CCD (71% vs. 95%, p 0.003). Likewise, USCD patients showed more frequent non-significant seronegativity (28% vs. 8%, p 0.07) and significantly lower titrations (7–15IU/ml) of tissue transglutaminase antibodies (tTG-IgA) (60% vs. 13%, p<0.001). Biopsies from D1 revealed significant less NK cells down-expression in USCD patients (1.4 vs. 5, p 0.04).

ConclusionsUp to 5.5% of CD patients showed USCD. A lower frequency of HLADQ2, along with less serum tTG-IgA titration and duodenal NK cell suppression, were differential features of USCD.

La enfermedad celiaca ultracorta (ECUC) es un nuevo fenotipo de la enfermedad celiaca, que afecta exclusivamente al bulbo duodenal (D1), cuyas características genéticas e inmunológicas no han sido descritas.

ObjetivosComparar las características genéticas, clínicas, serológicas, histológicas e inmunológicas entre ECUC y enfermedad celiaca convencional (ECC).

MétodosEstudio prospectivo, unicéntrico, en el que se realizaron biopsias duodenales a pacientes adultos y pediátricos que seguían una dieta con gluten. Se realizó análisis histológico y por citometría de flujo por separado de duodeno distal y D1. En pacientes seronegativos con histología o linfograma concordante con EC, se repitió la biopsia tras 2 años con dieta sin gluten.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 505 pacientes, siendo diagnosticados 127 de enfermedad celiaca, de los cuales 7 (5,5%) tenían ECUC. Los pacientes con ECUC expresaron el haplotipo DQ2 con menor frecuencia que en la ECC (71% vs. 95%, p 0,003) y presentaron mayor seronegatividad (28% vs. 8%, p 0,07) y, de manera significativa, titulaciones bajas de anticuerpos antitransglutaminasa (7-15IU/ml) (60% vs. 13%, p < 0,001). Comparado con la ECC, la citometría de flujo en las biopsias bulbares reveló una reducción atenuada significativa de células NK (1,4 vs. 5, p 0,04) en pacientes con ECUC.

ConclusionesUn 5,5% de los pacientes celiacos presentaron ECUC. Comparada con la ECC, las características diferenciales de la ECUC son menor expresión de HLADQ2, títulos más bajos de anticuerpos antitranglutaminasa y menor supresión de células NK a nivel bulbar.

Celiac disease (CD) is defined as an immune-mediated enteropathy, elicited by gluten and related prolamines in genetically susceptible individuals, affecting approximately 1% of the general population.1 Despite increased awereness, CD remains underdiagnosed due to a variety of reasons, including heterogeneous clinical presentation, mild or negative laboratory abnormalities and discordance among clinic, serologic and histologic findings. Revealing the submerged CD iceberg, therefore, requires high clinic suspicion while maximizing available diagnostic tests.

In this regard, a novel CD subtype coined ultra-short celiac disease (USCD) has been recently described in both children and adults.2,3 USCD refers to an enteropathy limited to the duodenal bulb (D1), which may represent early CD with a mild clinical, serological and histological phenotype. Immunophenotypically, CD is characterized by an increase in the absolute numbers of T-cell receptor gammadelta positive (TCRγδ+) intraepithelial lymphocites (IELs) up to 25% of all IELs, compared to 4% in healthy controls.4 Another abnormality observed in CD is a decrease in a subset of CD3-IELs with natural killer (NK) function, which become almost undetectable in active celiac disease.5 Two recent studies have demonstrated a high diagnostic accuracy of this celiac lymphogram for the diagnosis of CD, even in patients with seronegative villous atrophy.6,7 In a recent meta-analysis, this lymphogram pattern has proven to be useful in cases where the diagnosis of CD is not straightforward8 and, if available, it is recommended in current updated guidelines.1,9 This diagnostic tool has not been assessed in USCD patients yet. Differences in genetic characterization (human leukocyte antigen (HLA) haplotypes) between CD and USCD patients have not been evaluated either.

The present study aims to characterize baseline genetic, clinical, serological, histological and immunophenotypical changes in USCD patients, compared to those observed in patients diagnosed with conventional CD (CCD) and non-celiac controls.

Patients and methodsStudy populationAll pediatric and adult patients, without a previous diagnosis of CD, undergoing a clinically indicated upper endoscopy with duodenal biopsies at Hospital San Pedro de Alcantara, Caceres, Spain (between February 2015 and February 2018), were prospectively recruited. Patients included those with suspected CD due to positive serology, but also general and open-access referrals for anemia or any upper gastrointestinal symptom. All patients were on a gluten-containing diet at baseline endoscopy. In case of doubtful results and/or suspicion of gluten restriction, patients were re-scoped after an 8-week gluten challenge, with a daily consumption of a minimum of 12g of gluten per day. Patients in which CD was ruled out by means of histology and flow cytometry were considered as the control population. The investigations were conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval from the Institutional Review Board was obtained. All patients signed a specific informed consent for the study before enrollment.

Demographic dataAge, gender, family history of CD, gastrointestinal and extraintestinal symptoms, along with laboratory parameters, including, were systematically collected.

CD antibodies and HLA haplotypesBlood samples for serology, including IgA and both anti-tissue transglutaminase (tTG-IgA), were extracted from all included patients. If positive tTG-IgA (>7IU/mL) or high suspicion of seronegative CD, endomysial antibodies (EMA) were obtained. In case of IgA deficiency, tTG and EMA IgG were requested. tTG-IgA were assessed via fluorescence enzyme inmunoassay (Thermo Scientific) using ELiA™ GliadinDP IgA and IgG reagent (synthetic deaminated gliadin peptide), ELiA™ Celikey IgA and IgG (recombinant human tissue transglutaminase). EMAs antibodies were detected via staining of rhesus monkey esophagus substrate by indirect immunofluorescence assay (Menarini Diagnostics). Additional blood samples for HLA haplotypes were obtained in all CCD/USCD, as well as in some patients in the control group with high clinical suspicion of CD. HLA haplotypes DQ2 and DQ8 were determined by SSO (Kit LIFECODES HLA, Luminex Longwood).

Endoscopy and histologyAll patients underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy under endoscopist-directed propofol sedation. According to the study protocol, four biopsies were taken from distal duodenum and two from D1 for histopathological analysis. Each of the biopsy specimens was graded according to the modified Marsh criteria, to identify the presence and severity of villous atrophy. The Marsh criteria were applied consistently between the bulb and distal duodenum. All biopsies from CCD and USCD patients were carefully reviewed by a senior gastrointestinal pathologist (NF-G) with expertise on CD, who was blinded for clinical and serological data.

Flow citometry analysisTwo additional biopsy samples from D1 and two more from distal duodenum were obtained during endoscopy for flow cytometry analysis. Samples were placed in saline solution to avoid spontaneous de-epithelization and immediately transferred to the laboratory in the department of Immunology.

Epithelial and intraepithelial cells were isolated from intestinal biopsies as described elsewhere.10 Both TCRγδ+ and NK cells were selected, which were measured as CD45+CD103+TCRγδ+ and CD45+CD3−CD103+, respectively, over the total CD45+CD103+ cells. The results were assessed by two immunologists (LF-P, CC-H), who were blinded to the results of serology and histology. The celiac lymphogram was defined as an increase in TCRγδ+ cells ≥10% plus a concomitant decrease in NK cells ≤10%.7

Diagnosis of CCD and USCDA diagnosis of CD was made upon the combination of compatible symptoms, serology and histology/flow citometry findings.1 CCD patients showed pathological and ultrastructural changes at both D1 and distal duodenum, whereas these changes were confined to D1 in patients with USCD.

In cases of symptomatic seronegative patients with histology/flow cytometry consistent with CD/USCD, HLA haplotyples were performed. If positive, a thorough re-examination looking for alternative causes of histologic findings (including H. pylori infection, parasites, medications, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, inflammatory bowel disease), was performed.12 After these potencial causes were ruled out, patients were given a diagnosis of possible CD/USCD and were re-scoped after a minimum of 2 years on a strict gluten-free diet (GFD), with the same biopsy protocol. Subjective symptom improvement, normalization of histological findings (Marsh 0) and NK cell count in flow cytometry on a GFD, were required for a definitive CD/USCD diagnosis.11–13

Statystical analysisDemographic characteristics of CD and USCD patients and non-celiac controls were compared using the Chi-Square test (categorical data) and the t-test (quantitative data). Median and 25–75th percentiles were used to express the densities of IELs in celiac and non-celiac patients. Significance was set at p<0.05. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp) was used for all statistical analyses.

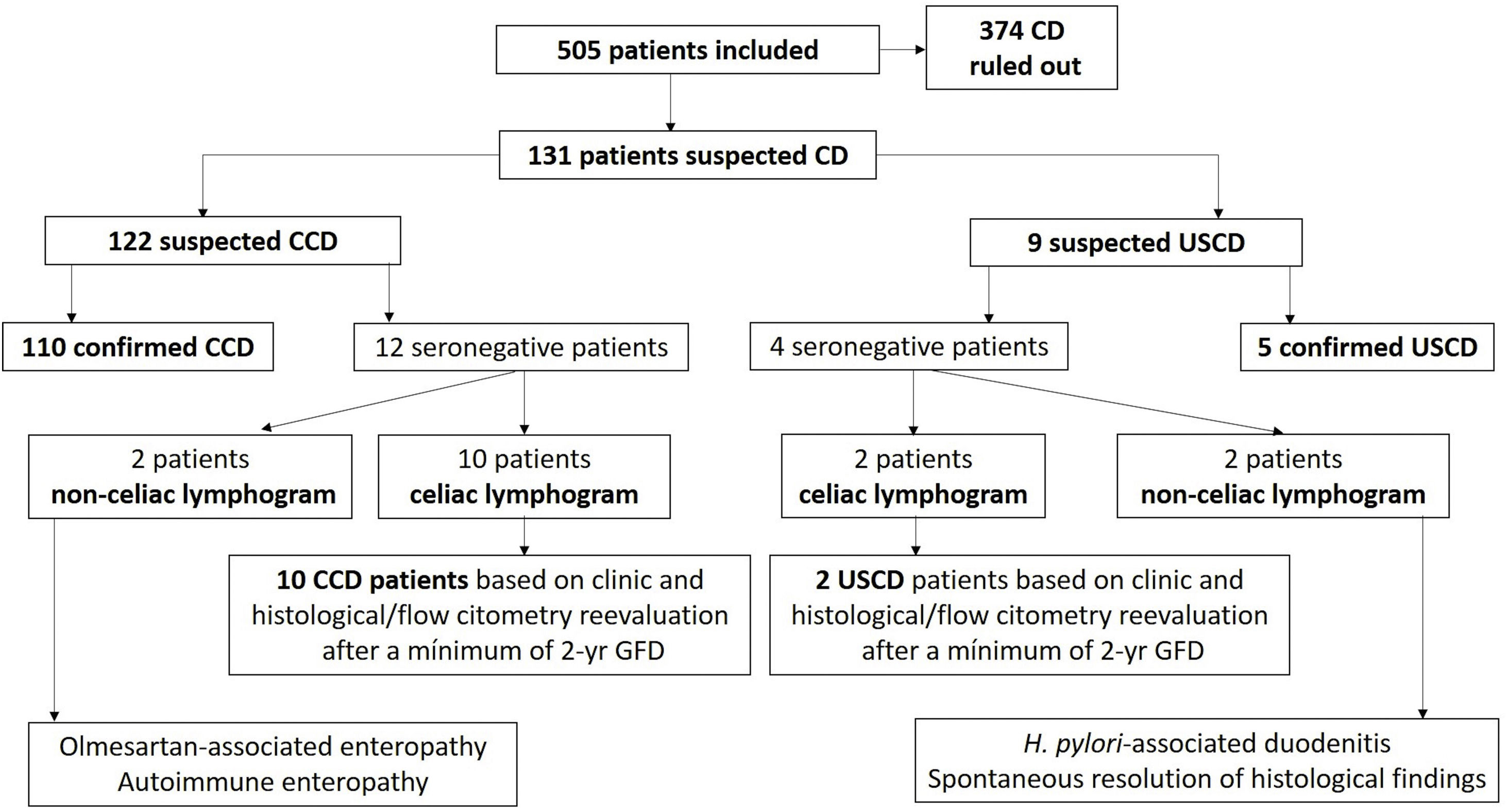

ResultsFlow chart of patients and demographicsA total of 505 patients, of whom 95 (19%) were children, were included. CD was finally diagnosed in 25% of the evaluated population (127 patients), of whom 7 (5.5%) suffered from USCD (3.8% in children, 6.6% in adults). The flow chart of patients during the study is shown in Fig. 1. Among controls (n=378), 85% (n=321) exhibited normal duodenal biopsies (Marsh 0) with normal flow cytometry features. The remaining 57 patients showed non-specific histologic findings (Marsh I–II), with normal celiac lymphogram, negative antibodies and/or negative HLA haplotypes in all cases.

Demographic characteristics, clinical manifestations, and laboratory findingds in all evaluated populations are displayed in Table 1. Compared to CCD, USCD patients showed a significant higher frequency of dyspepsia (42% vs. 9%, p 0.006). Likewise, USCD exhibited fewer bowel habit changes, less hypoferritinemia, and more common family history of CD. No statistical differences were observed when comparing these parameters, likely due to small sample size in USCD patients.

Baseline demographic, clinic and laboratory findings in the study population.

| Controls(n=378) | p | CCD(n=120) | USCD(n=7) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age, yrsMean (range) | 41 (1–85) | <0.001 | 25 (1–73) | 19 (4–32) | 0.4 |

| Children<14 yrs | 41 (11%) | <0.001 | 50 (42%) | 2 (28%) | 0.4 |

| Female gender | 268 (71%) | 0.1 | 74 (58%) | 4 (50%) | 0.8 |

| Familial history of CD | 26 (7%) | <0.001 | 33 (28%) | 4 (57%) | 0.1 |

| Concomitant autoinmune diseases | 41 (11%) | 0.1 | 21 (18%) | 1 (14%) | 0.8 |

| Clinical manifestations | |||||

| Alternating bowel habit | 75 (20%) | 0.3 | 22 (18%) | 0 | 0.2 |

| Diarrhea | 143 (38%) | 0.4 | 44 (37%) | 1 (14%) | 0.2 |

| Abdominal pain | 234 (62%) | 0.04 | 59 (49%) | 4 (50%) | 0.7 |

| Bloating | 120 (32%) | 0.06 | 26 (22%) | 1 (14%) | 0.6 |

| Dyspepsia | 124 (33%) | <0.001 | 11 (9%) | 3 (42%) | 0.006 |

| Heartburn | 53 (14%) | 0.05 | 8 (7%) | 0 | 0.4 |

| Nausea, vomiting | 94 (25%) | 0.08 | 21 (17%) | 0 | 0.2 |

| Asthenia | 34 (9%) | 0.1 | 5 (4%) | 0 | 0.6 |

| Laboratory findings | |||||

| Anemia | 124 (33%) | 0.9 | 40 (33%) | 2 (28%) | 0.8 |

| Hypoferritinemia | 87 (23%) | 0.002 | 48 (37%) | 1 (14%) | 0.2 |

HLADQ2 was significantly less common in USCD compared to CCD (71% vs. 95%, p 0.003). HLADQ2 was present in 42% of control population. There were no differences in regards to HLADQ8 haplotype (14% vs. 15%, p 0.7). Only one patient among 7 USCD (14%) did not express neither DQ2 nor DQ8 haplotyples, whereas all patients in the CCD group showed DQ2, DQ8 or both haplotypes.

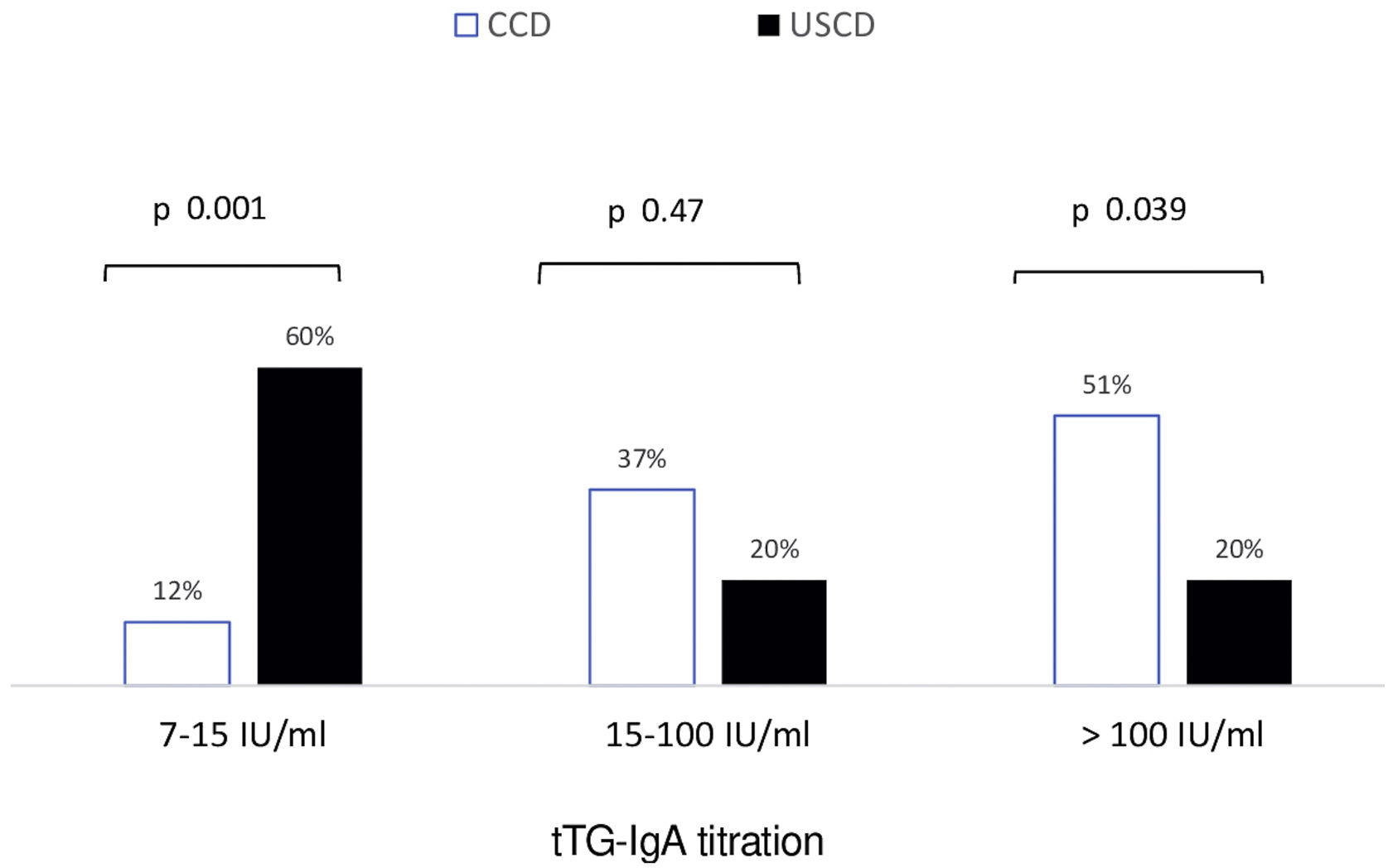

CD antibodiesSeronegativity (tTG-IgA<7IU/mL) was borderline significantly more common in patients with USCD than in those with CCD (28% vs. 8%, p 0.07). No seronegative patient in both groups exhibited positive anti-EMA. In patients with positive serology (anti-tTG≥7IU/mL), baseline antibody titration for tTG-IgA in CCD and USCD patients is shown in Fig. 2. Low titration of tTG-IgA between 7 and 15IU was significantly more frequent in USCD patients [60% vs. 12%, p<0.001].

HistologyPrior to the present study, a total of 22 patients (4%) had normal duodenal biopsies (not including duodenal bulb), taken in the context of high suspicion of CD. Noteworthy, 5 out of 7 of USCD (70%) belonged into this group, of whom 3 (42%) were diagnosed with potential CD based on symptoms and positive serology, but normal histological findings in distal duodenum biopsies. Histological results in USCD and CCD patients, both in D1 and distal duodenum, are exhibited in Table 2. The presence of villous atrophy (Marsh 3) was similar in both groups (86% D1 in USCD vs. 87% distal duodenum in CCD). Of note, villous atrophy in D1 could only be documented in 60% of CCD patients. Two patients in the control population were diagnosed with seronegative villous atrophy and non-celiac flow cytometry. Both patients were finally diagnosed with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)-related petic duodenitis. Histological normalization was checked after acid suppression and eradication therapy in both patients.

Histological differences in separated duodenal biopsies between evaluated populations.

| Controls(n=374) | p* | CCD(n=120) | USCD(n=7) | p** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | |||||

| Villous atrophy (Marsh 3) | 2 (0.5%) | <0.001 | 72 (60%) | 6 (86%) | 0.5 |

| Non-specific findings | 183 (48%) | <0.001 | 32 (40%) | 1 (14%) | 0.9 |

| Marsh 0 | 191 (51.5%) | <0.001 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Distal duodenum | |||||

| Villous atrophy (Marsh 3) | 2 (0.5%) | <0.001 | 105 (87%) | 0 | <0.001 |

| Non-specific findings | 104 (27%) | <0.001 | 15 (13%) | 7 (100%) | <0.001 |

| Marsh 0 | 268 (71%) | <0.001 | 0 | 0 | – |

Total IELs count was similar in controls, USCD and CCD patients, whereas significant differences (p<0.001) were observed in TCRγδ+ and NK cells counts, when comparing controls and USCD/CCD patients. Results regarding TCRγδ+ IELs and NK cells in D1 and distal duodenum are shown in Table 3. No relevant differences were observed between USCD and CCD in TCRγδ+ counts, neither in D1 nor in distal duodenum. While NK cells were significantly suppresed in D1 in CCD, this phenomenon was less marked in D1 in USCD (1.4 CCD vs. 5 USCD, p 0.04). Since distal duodenum is not affected in USCD, NK cells counts from distal duodenum in USCD patients were similar to those found in the control population.

Immunophenotypic differences in duodenal biopsies between evaluated populations. Results are expressed as mean (range).

| Controls(n=374) | p* | CCD(n=120) | USCD(n=7) | p** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | |||||

| IELs | 87 (76–99) | 0.6 | 89 (74–99) | 86 (68–98) | 0.5 |

| TCRγδ+ IELs | 10 (0.6–20) | <0.001 | 32 (9–80) | 26 (11–48) | 0.3 |

| NK cells | 20 (0.1–65) | <0.001 | 1.4 (0–6) | 5 (1.5–14) | 0.04 |

| Distal duodenum | |||||

| IELs | 90 (82–99) | 0.8 | 91 (77–99) | 92 (81–97) | 0.7 |

| TCRγδ+ IELs | 9 (0.1–18) | <0.001 | 29 (1.5–76) | 17 (2–32) | 0.5 |

| NK cells | 17 (0–74) | <0.001 | 3 (0–41) | 14 (3–36) | <0.001 |

The flow chart of patients during the diagnostic work-up is detailed in Fig. 1. Among patients with suspected USCD, there were two seronegative patients, of whom 1 had villous atrophy and the other showed Marsh II changes on bulb biopsies. Both showed HLA haplotyples, symptoms and typical celiac lymphogram in flow cytometry from bulb biopsies, all compatible with CD. Full remission, as described in the method section, was accomplished in both patients after implementation of a GFD. Interestingly, one of these patients did not express typical celiac haplotypes (DQ2 and DQ8).

As for patients with suspected CCD, there were 12 seronegative patients. Two of them had villous atrophy with a non-celiac lymphogram. Final diagnostic work-up revealed olmesartan-associated enteropathy and autoimmune enteritis. With regards to the remaining ten patients, 5 showed villous atrophy and the other five non-specific histological findings (Marsh I–II). All ten patients had HLA haplotyples, symptoms and typical celiac lymphogram in flow cytometry, consistent with CD. All of them started a GFD with symptom resolution, along complete histological resolution and NK cells normalization after a minimum of 2 years on a GFD.

DiscussionThe present study first reports data on genetic and duodenal immunophenotypic inflammatory changes in pediatric and adult patients with USCD. To begin with, there was a significant lower presence of the DQ2 haplotype in USCD. The HLA-DQ2.5 heterodimer, one variant of the DQ2 molecule, is the most permissive heterodimer for celiac disease, encoded by approximately 90% of patients with CD.14 In fact, HLADQ2 homozygosis has been recently shown to confer a much higher risk (25–30%) of developing early-onset CD in infants with a first-degree family member affected by the disease.15 Our findings suggest a lower frequency of the key permissive HLADQ2 heterodimer in USCD. Secondly, baseline NK cells suppression in USCD was significantly lower when compared to CCD patients. NK cells are a first line of immunological defence, and suppression of NK cell cytotoxic receptors represents one of the strategies to escape the host's immune system. Active inflammation in untreated CD correlates with a sharp reduction of NK cells,16 whereas NK cells count tend to normalize on duodenal biopsies after a GFD is instituted.10 Whether if a higher expression of duodenal NK cells at baseline in USCD may hint at some degree of immunotolerance, remains to be elucidated. Recently, it has been hypothesized that USCD might be an initial form of CCD.2 The present study shows in USCD down-expression of HLADQ2 heterodimer, less tTG-IgA titration and less reduction in NK cells. Hence, it is conceivable to speculate that USCD might be an attenuated CD phenotype with incomplete inflammatory expression. It is unknown if this suggested attenuated phenotype is only present at early stages of USCD, or different forms of complete and incomplete inflammatory may coexist. The small sample size of the present study is a clear limitation to draw any conclusion, so further bigger studies should shed light on this hypothesis.

The frequency of USCD reported in the present study is slightly lower than those previously reported,2,3 around 1 in 10 of CD patients. We do believe this may merely be a reflection of differences in evaluated populations or participating centers. Our adult gastroenterology department is not referral for upper endoscopy or CD study. As for children, the biopsy-sparing ESPGHAN guidelines for CD diagnosis in children, published in 201217 and validated in 2017,18 may have modified our diagnostic picture in children. In any case, our USCD/CD diagnostic rate in the overall evaluated population reinforces the lack of usefulness of duodenal biopsies in non-selected patients.19

Both seronegativity and lower titer of antibodies were significantly higher in USCD, in accordance with previous reports.2,3 This lower titer may just mirror a limited level of antibodies related to limited extent of bowel involvement. Up to 70% of USCD in our series exhibited previous normal duodenal biopsies and up to 42% of USCD patients in our series had a previous diagnosis of potential CD (normal histology with symptoms and positive serology).1,9 While progression to villous atrophy has been recently described in almost half patients with potential CD,20 we do humbly speculate that either poor biopsy sampling combined with lack of inclusion of D1 biopsies was the most likely reason for misdiagnosis in this subset of our patients.

Seronegative CCD patients (8%) included in the present study is in full accordance with previous reports.13,21 Inclusion of seronegative patients without villous atrophy might be more controversial, but typical symptoms, HLA haplotypes and celiac lymphogram were present in all of them. The diagnostic supporting role of flow cytometry of this difficult-to-diagnose patients has been recently confirmed in systematic reviews and meta-analyses8 and updated iterations of diagnostic guidelines.1,9 Additionally, these patients were carefully followed-up with documented resolution of clinic, histologic and flow cytometry findings on a GFD. All of our controversial CCD and USCD patients achieved complete histological remission after a minimum of 2 years on a GFD. These findings contrast with those shown by a recent prospective multicenter study conducted in adults, in which up to 50% may have persistent villous atrophy after 2 years on a GFD.22 Some potential reasons for this discrepancy may be less severe lesions and longer GFD duration in our study. On another level, it may be reasonably questionable whether a strict GFD might be required for USCD patients, since it seems to be an early milder phenotype associated with fewer micronutrient deficiencies.2,3 Symptomatic, histologic and immunological improvement observed in the present study for seronegative USCD patients, similar to that found in patients with seronegative CCD, appear to suggest that the immune cascade was switched off in both cases and may fully justify a strict GFD for USCD.

The present study has several drawbacks, mainly recruitment from a single center and a small simple size, specially in the USCD group. The lack of dietitian or gluten immunogenic peptide tests to monitor adherence to a GFD in patients undergoing follow-up endoscopy are also potential limitations. It could have been also useful to perform gluten provocation tests in order to reproduce symptoms and/or histological/immunological features in difficult-to-diagnose patients (e.g, seronegative coeliac disease or HLA-DQ2-DQ8 negative cases).23,24 Strengths to the study may include evaluation of HLA haplotypes and immunophenotypic data from flow cytometry, separating D1 and distal duodenum information, in USCD and CCD patients, as well as careful follow-up of seronegative patients, including flow cytometry data.

In conclusion, USCD was found in 5.5% of pediatric and adult patients in our series, supporting the importance of optimal D1 sampling in CD histologic diagnostic work-up. Novel findings for USCD include a lower frequency of HLADQ2 and a different cytometry pattern, with a limited down-expression of NK cells. These data suggest that USCD may be an early form of CD with an attenuated inflammatory phenotype.

Authors’ contributionP M-R and D M-H: inclusion of patients, data acquisition/interpretation, drafting of the article, critical revision; HC F-N, PL G-C, A I-M, P B-G: inclusion of patients, critical revision; N F-G: histopathologic analysis, critical revisión; L F-P, C C-H: laboratory work, critical revisión; J M-I: study design, inclusion of patients, data interpretation, drafting of the article, critical revision

Funding sourcesThe authors did not receive any fundings for the present study.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest regarding its content.

We are grateful to the Department of Immunology at Hospital Universitario de Badajoz, Extremadura, Spain, who were responsible for laboratory work related to HLA haloptypes.