Cowden syndrome (CS) is a rare genetic disease characterised by the development of hamartomas that can affect multiple organs, with an increased risk of different types of cancer. Although hamartomatous polyps are common, it is less common to find intestinal ganglioneuromas as the first sign.1,2

We present the case of a patient with ganglioneuromatous polyposis in whom the final diagnosis of CS was arrived at through the other extra-intestinal manifestations.

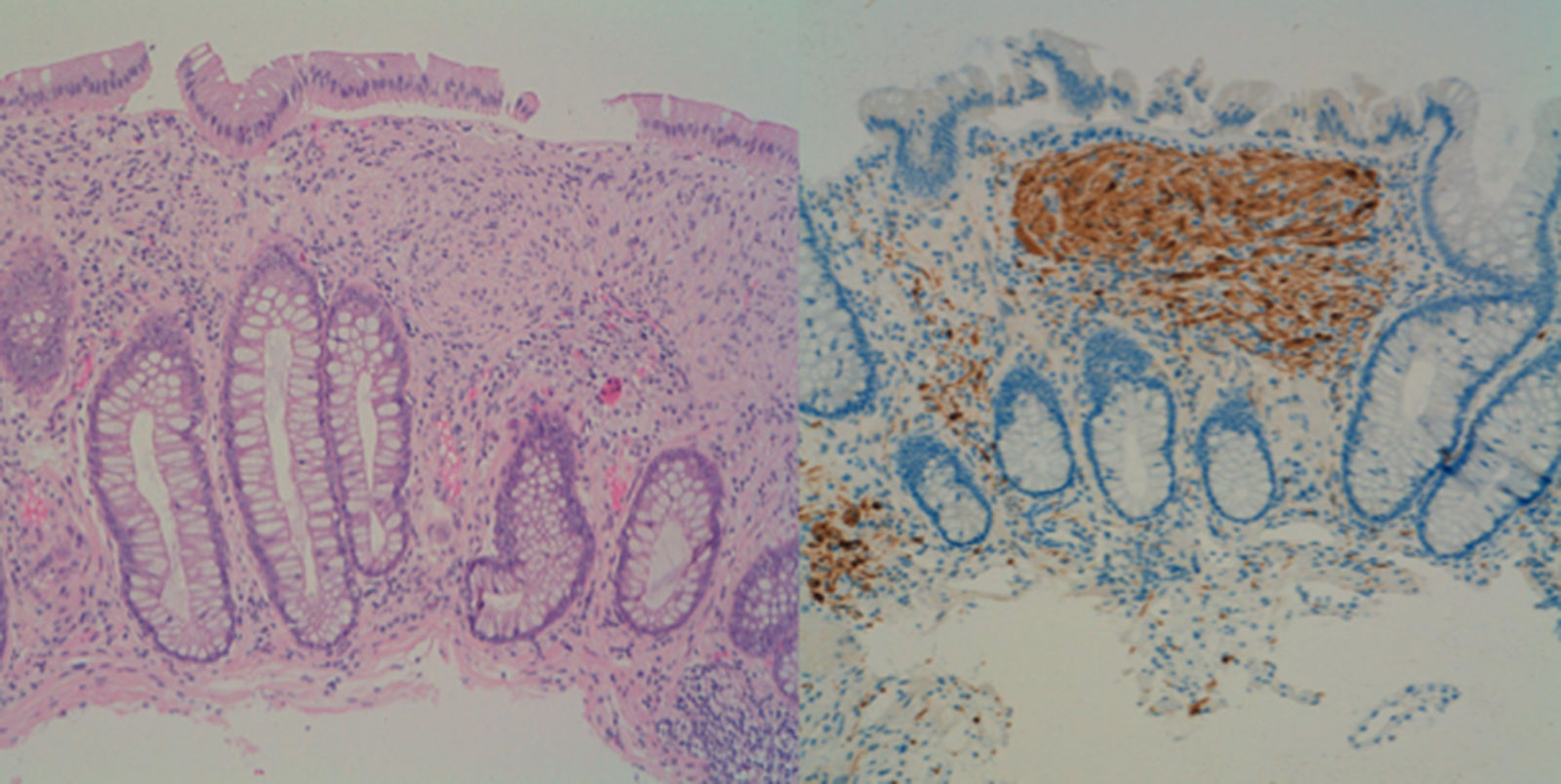

This was a 39-year-old man who was referred for colonoscopy with a history of a first-degree relative having died of colorectal cancer (CRC). Colonoscopy showed more than 100 polyps, distributed throughout the colon, but more predominant on the left side. Following the resection of several of these polyps, the histology showed a diffuse mesenchymal proliferation of spindle cells with scattered ganglion cells in lamina propria, all compatible with ganglioneuromatous polyps (Fig. 1). In view of these findings, we requested a gastroscopy which showed an extensive glycogenic acanthosis in the oesophagus and more than 100 polyps in the second part of the duodenum, mostly millimetric in size, corresponding to tubular adenomas with moderate dysplasia.

On questioning about his previous medical history, the patient reported having had a hemi-thyroidectomy for adenoma and the resection of a collagen fibroma in his right flank. On examination, we found obvious macrocephaly (studied in childhood and attributed to rickets) and the presence of brownish pigmented macules on his penis.

After confirming from all these findings that the patient met clinical criteria for CS,3 complete sequencing of the PTEN gene study was performed, obtaining a pathogenic mutation (p.Arg130Gln) in exon 5 associated with CS. Further tests ruled out an association with type ii multiple endocrine neoplasia.

Ganglioneuromatosis is caused by hyperplasia of the myenteric plexuses and enteric nerve fibres. Clinically, there are three distinct types: (1) polypoid ganglioneuromatosis, which consists of few isolated ganglioneuromas; (2) generalised ganglioneuromatosis, which is associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type IIb and von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis; and (3) ganglioneuromatous polyposis, without associated systemic disease, in which category our case falls into.2

CS is a hereditary disease, with autosomal dominant transmission, due to germline mutation in the PTEN tumour-suppressor gene. Its prevalence is estimated at one case per 200,000–250,000 population.4

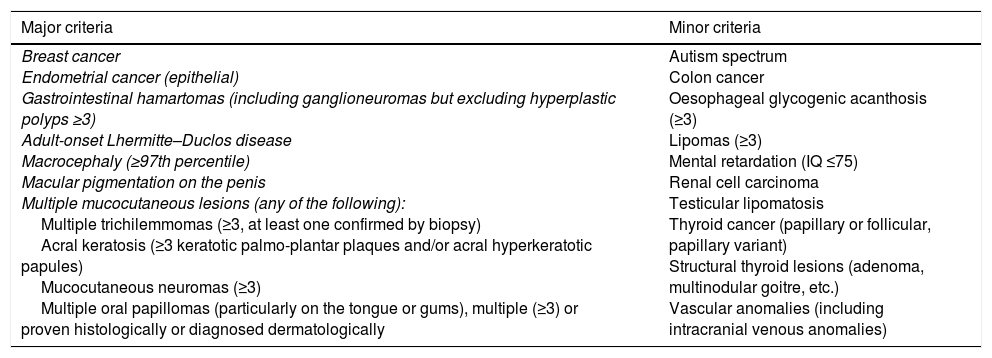

Initially, diagnostic criteria were proposed that included major and minor pathognomonic criteria.5 Because of their lack of specificity, Pilarski et al. proposed alternative criteria which have been adopted by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. One of the main differences is that gastrointestinal hamartomas, including ganglioneuromas, are included as major criteria (Table 1).3

Modified diagnostic criteria for Cowden syndrome.

| Major criteria | Minor criteria |

|---|---|

| Breast cancer Endometrial cancer (epithelial) Gastrointestinal hamartomas (including ganglioneuromas but excluding hyperplastic polyps ≥3) Adult-onset Lhermitte–Duclos disease Macrocephaly (≥97th percentile) Macular pigmentation on the penis Multiple mucocutaneous lesions (any of the following): Multiple trichilemmomas (≥3, at least one confirmed by biopsy) Acral keratosis (≥3 keratotic palmo-plantar plaques and/or acral hyperkeratotic papules) Mucocutaneous neuromas (≥3) Multiple oral papillomas (particularly on the tongue or gums), multiple (≥3) or proven histologically or diagnosed dermatologically | Autism spectrum Colon cancer Oesophageal glycogenic acanthosis (≥3) Lipomas (≥3) Mental retardation (IQ ≤75) Renal cell carcinoma Testicular lipomatosis Thyroid cancer (papillary or follicular, papillary variant) Structural thyroid lesions (adenoma, multinodular goitre, etc.) Vascular anomalies (including intracranial venous anomalies) |

Diagnosis is established in an individual who meets either of the following conditions: three or more major criteria, but one must include macrocephaly, Lhermitte–Duclos disease or gastrointestinal hamartomas; or two major and three minor criteria.

In the case of families where an individual meets the diagnostic criteria or has mutation in the PTEN gene, the diagnosis is established when any of the following conditions are met: (a) any two major criteria, with or without minor criteria; or (b) one major and two minor criteria; or (c) three minor criteria.

Source: Pilarski et al.3

Mucocutaneous lesions (98%), macrocephaly (93%), gastrointestinal polyps (93%) and benign lesions of the breast (74%) and thyroid (71%) are the most common manifestations.6 In the gastrointestinal tract, one of the most common manifestations is glycogenic acanthosis of the oesophagus. Despite their non-specificity, it has been proposed that oesophageal acanthosis and colon polyposis should be considered as pathognomonic criteria for CS. Gastroduodenal polyps have been described in 67–100%, the majority hamartomatous and hyperplastic, but also adenomas. As far as involvement of the colon is concerned, 92% have polyps, varying from a few to countless. What is interesting is the coexistence of multiple histological types, which include hamartomas, hyperplastic polyps, ganglioneuromas and adenomas.7

However, the most important factor is the risk of malignant tumours. Several studies have reported the same increased risk of cancer of the breast (25–50%), endometrium (13–28%), thyroid (3–17%) and kidney (2–5%).8,9 In contrast to what was previously believed, there is also an increased risk of CRC. Heald et al. reported that out of 67 patients (mean age 44.4) with CS who had colonoscopies, 13% had CRC.10 In a subsequent study, the estimated risk was 10.3 times higher (95% CI: 5.6–17.4, p<0.001) than in the general population.8 Another study with 154 patients found the estimated risk to be 5.7 times higher (95% CI: 1.14–16.64, p=0.036).9 In a multicentre study that included 156 patients, the cumulative risk of CRC was 18% at age 60.11

The importance of early diagnosis lies in preventing associated tumours. While there is consensus on the need for surveillance of extra-intestinal manifestations, there is less agreement on endoscopic follow-up. The American guidelines for the management of hereditary syndromes recommends starting with colonoscopy at age 15 and repeating every two years.12 Other authors, however, propose less aggressive surveillance, starting at age 35–40 and repeating every two years if they have a high rate of polyps or every three to five years if they have a low rate.8,13 They also recommend gastroscopy at the time of diagnosis and at five-year intervals, or less, depending on the findings.10

In conclusion, given the fact that multiple histological types can coexist in intestinal polyposis, it is important to assess the extra-intestinal manifestations that help us determine the end diagnosis, since the surveillance and management will be different in each case.

Please cite this article as: Adán Merino L, Aldeguer Martínez M, Álvarez Rodríguez F, Barceló López M, Plaza Santos R, Valentín Gómez F. Manifestación inicial atípica de una poliposis poco frecuente, el síndrome de Cowden. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:315–317.