Tuberculosis, a chronic infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, may invade all organs but mainly affect the lungs. We report a case of disseminated tuberculosis with hepatic, pericardial and pleural involvement and a review of the relevant literature. A 64-year-old Portuguese male was admitted with epigastric and right upper quadrant pain associated with low grade fever, fatigue, nausea, anorexia, weight loss (6kg) and mild jaundice. A chest X-ray showed cardiomegaly and a computed tomographic scan of the thorax and abdomen revealed a mild left pleural effusion, a thickened pericardium with signs of incipient calcification and hepatomegaly. The echocardiogram suggested the diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis. Liver biopsy revealed granulomatous lesions with central caseating necrosis. Tuberculosis is usually associated with atypical clinical manifestations. Imaging examination combined with histopathological features, a high index of clinical suspicion and improvement with antibacilar therapeutic are necessary to confirm a diagnosis, especially in the cases of extrapulmonary tuberculosis.

A tuberculose, uma doença infecciosa causada pelo Mycobacterium tuberculosis, pode invadir todos os órgãos, afectando sobretudo os pulmões. Relatamos um caso de tuberculose hepática com envolvimento pericárdico e pleural e uma revisão da literatura relevante. Um homem de 64 anos, de nacionalidade portuguesa, foi admitido por dor no quadrante superior direito do abdómen e no epigastro associada a febre baixa, astenia, náuseas, anorexia, perda de peso (6kg) e icterícia. A radiografia de tórax revelou cardiomegalia e a tomografia computadorizada de tórax e abdómen revelou um derrame pleural esquerdo ligeiro, um pericárdio espessado com sinais incipientes de calcificação e hepatomegalia. O ecocardiograma era sugestivo de pericardite constritiva. A biopsia hepática revelou granuloma com necrose caseosa central. A tuberculose geralmente está associada a manifestações clínicas atípicas. A presença de aspectos imagiológicos em conjunto com características histológicas típicas, um elevado índice de suspeita clínica e resposta à terapêutica antibacilar são necessários para confirmar o diagnóstico, especialmente nos casos de tuberculose extrapulmonar.

Tuberculosis (TB) can present with a variable clinical picture, consequently, making the diagnosis difficult. Disseminated tuberculosis (TB) is defined as having two or more noncontiguous sites resulting from lymphohematogenous dissemination of Mycobacterium tuberculosis.1 Extrapulmonary involvement occurs in one-fifth of all TB cases2 and it may occur in the absence of histological and radiological evidence of pulmonary infection.

Hepatic tuberculosis, particularly in the absence of miliary tuberculosis, is rare3 and can occur as a primary case or due to reactivation of an old tubercular focus.3

Diagnosis is often difficult as clinical manifestations are nonspecific and because it can mimic several other disorders. Clinically, hepatic tuberculosis can present as fever of unknown origin, abdominal pain and jaundice, which if not timely diagnosed and properly managed can culminate in fulminant hepatic failure that may prove fatal.4

Pericardial involvement in tuberculosis may result in acute pericarditis, chronic pericardial effusion, cardiac tamponade or pericardial constriction.5 The disease has insidious onset and patients may present with fever and can manifest vague precordial pain or cardiomegaly on a chest radiograph.

Definitive diagnosis of extrapulmonary TB can be very difficult; it relies on histological and/or bacteriological findings of the liver tissue obtained by biopsy.6 Sometimes, clinical diagnosis is only confirmed after complete recovery with specific treatment.6

2Case reportA previously healthy 60-year-old Portuguese male presented with intermittent sharp epigastric and right upper quadrant pain in the last 2 weeks, low grade fever, fatigue, nausea, anorexia and weight loss (6kg) in previous 2 months. He admitted moderate alcohol consumption.

There was no previous history of similar pain and his past medical history was uneventful as well as his family history.

On physical examination at admission, he had a temperature of 37.2°C, a heart rate of 102/min, a blood pressure of 110/79mmHg and a respiratory rate of 24 breaths per minute with oxygen saturation of 98% on ambient air. He was alert but appeared uncomfortable, had mild jaundice and moderate tenderness in the right upper abdomen with palpable hepatomegaly. Cardiovascular examination revealed sinus rhythm; jugular veins were distended to the angle of the mandible when the patient sat upright, but no further venous engorgement was noted on inspiration and no peripheral edema was found. No enlargement of the superficial lymph nodes was found.

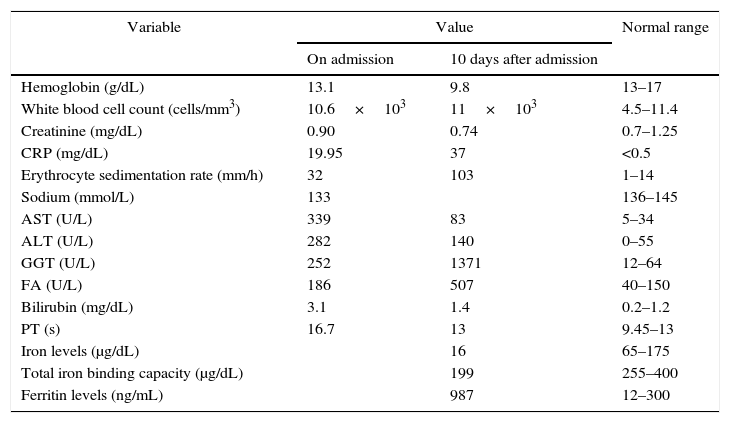

Initial blood tests investigations (Table 1) reported normal hemogram and renal function; mild hyponatremia 133mmol/L; elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) 19.95mg/dL; abnormal liver tests with alanine aminotransferase (ALT) of 282U/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 339U/L, alkaline phosphatase (AP) of 186U/L, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) of 252U/L, total bilirubin of 3.1mg/L with a direct fraction of 2.0mg/dL; and prothrombin time (PT) was 16.7s. Amylase and lipase were within normal ranges as well as cardiac markers, other serum electrolytes and urinalysis. Electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia, abdominal ultrasonography revealed hepatomegaly and slightly coarse echotexture of the liver, suggesting hepatic steatosis and chest X-ray revealed only a small left pleural effusion.

Laboratory values.

| Variable | Value | Normal range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| On admission | 10 days after admission | ||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.1 | 9.8 | 13–17 |

| White blood cell count (cells/mm3) | 10.6×103 | 11×103 | 4.5–11.4 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.90 | 0.74 | 0.7–1.25 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 19.95 | 37 | <0.5 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/h) | 32 | 103 | 1–14 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 133 | 136–145 | |

| AST (U/L) | 339 | 83 | 5–34 |

| ALT (U/L) | 282 | 140 | 0–55 |

| GGT (U/L) | 252 | 1371 | 12–64 |

| FA (U/L) | 186 | 507 | 40–150 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 3.1 | 1.4 | 0.2–1.2 |

| PT (s) | 16.7 | 13 | 9.45–13 |

| Iron levels (μg/dL) | 16 | 65–175 | |

| Total iron binding capacity (μg/dL) | 199 | 255–400 | |

| Ferritin levels (ng/mL) | 987 | 12–300 | |

CRP, C-reactive protein; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AP, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase; PT, prothrombin time.

After blood and urine cultures were taken, antibiotic therapy (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid) was initiated at the Emergency room because of the suspicion of an infectious process, and the patient was transferred to Gastroenterology ward to further investigation. During the first few days of hospital stay, there was improvement of right upper abdominal pain but afterwards the patient started to complain of a precordial sharp pain worsening with deep inspiration and had evening fever (up to 39.5°C), with chills and sweating. Additional study (Table 1) showed anemia (Hb=9.8g/dL) of chronic illness with low iron levels of 16μg/dL, low total iron binding capacity of 199μg/dL and high ferritin of 987ng/mL; leukocytosis (11×103cells/mm3) with neutrophilia (78%); his erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was elevated to 103mm/h and the CRP peaked to 37mg/dL. Peripheral blood immunophenotypage did not show any abnormality as well as blood smear. There was an improvement of transaminases (AST=83U/L and ALT=140U/L) and normalization of bilirubin values but the cholestasis parameters worsened, with GGT reaching up to 1371U/L and AP to 507U/L.

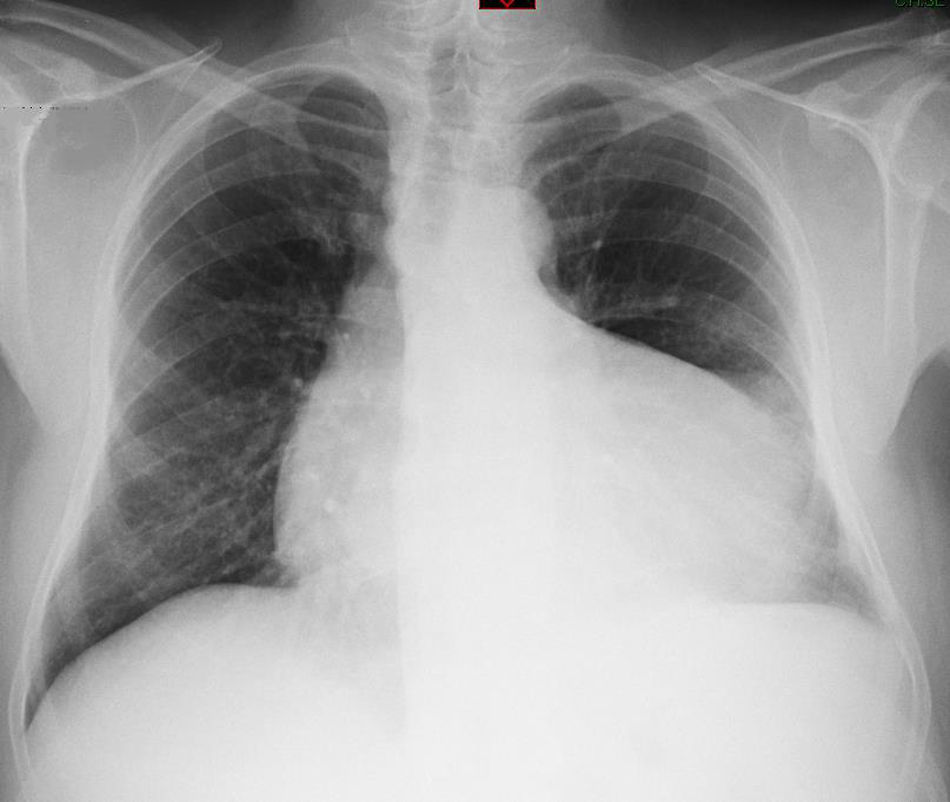

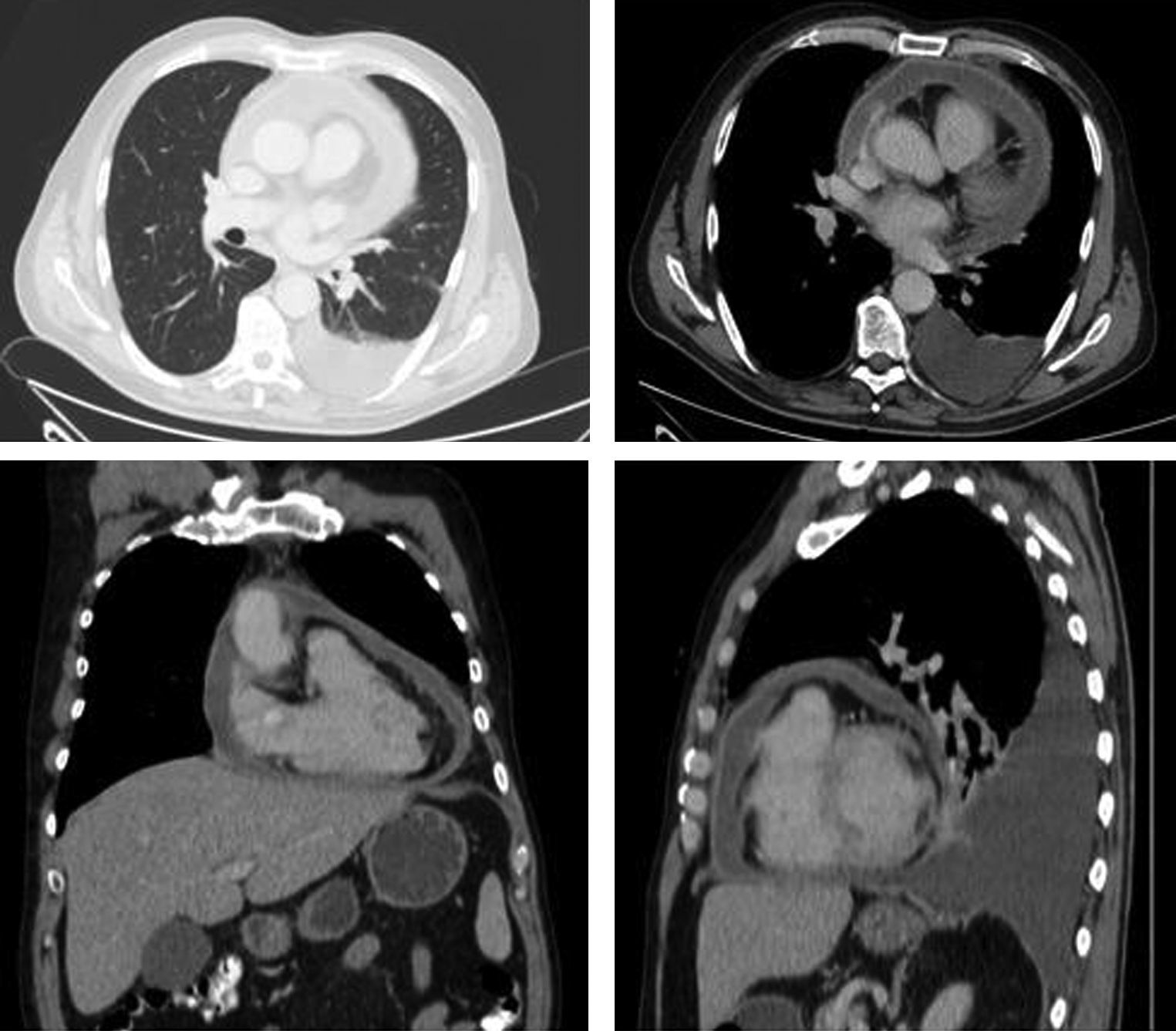

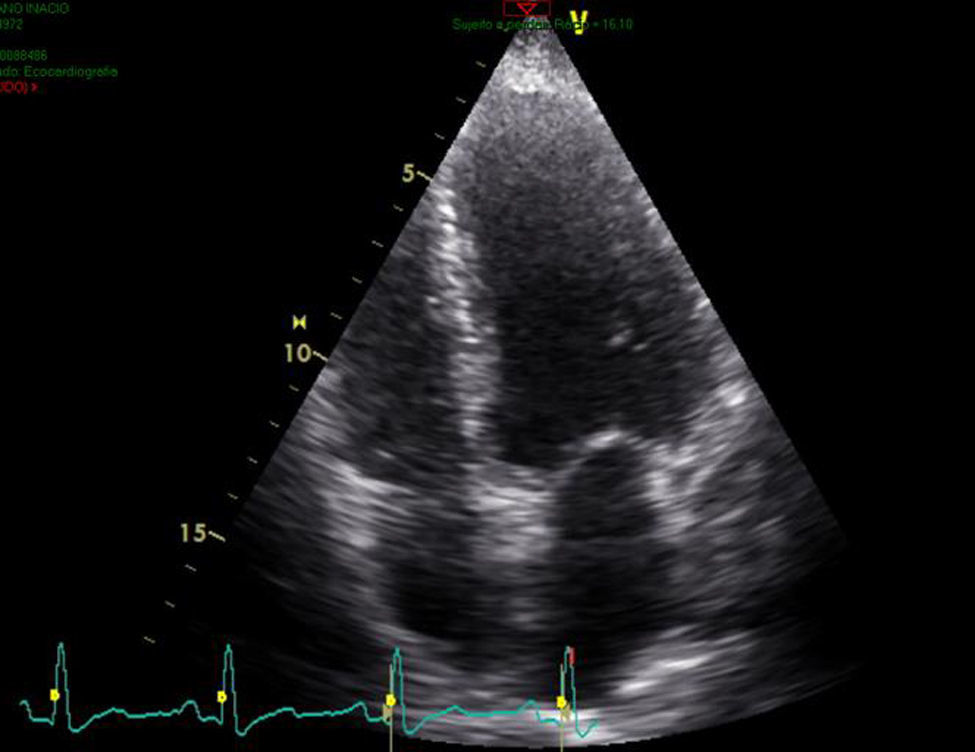

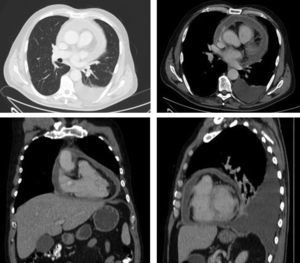

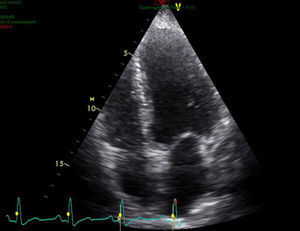

A chest X-ray showed a discrete left pleural effusion and now there was cardiomegaly (Fig. 1) and a computed tomographic (CT) scan of the thorax and abdomen revealed a mild left pleural effusion, a thickened pericardium with signs of calcification (Fig. 2) and hepatomegaly. The echocardiogram (Fig. 3) with color Doppler suggested the diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis (CP), with a thickened pericardium and incipient calcification predominantly over right heart, without signs of hemodynamic compromise.

Blood, sputum, and urine were all negative for bacteria and acid-fast bacilli on both smears and mycobacterial cultures. Thoracic ultrasonography revealed a small quantity of pleural effusion, which precluded thoracentesis. The tuberculin test revealed no induration; however interferon gamma release assay (IGRA) Quantiferon test was positive. Serology for hepatitis virus, HIV and syphilis and autoimmune tests were negative (Table 2).

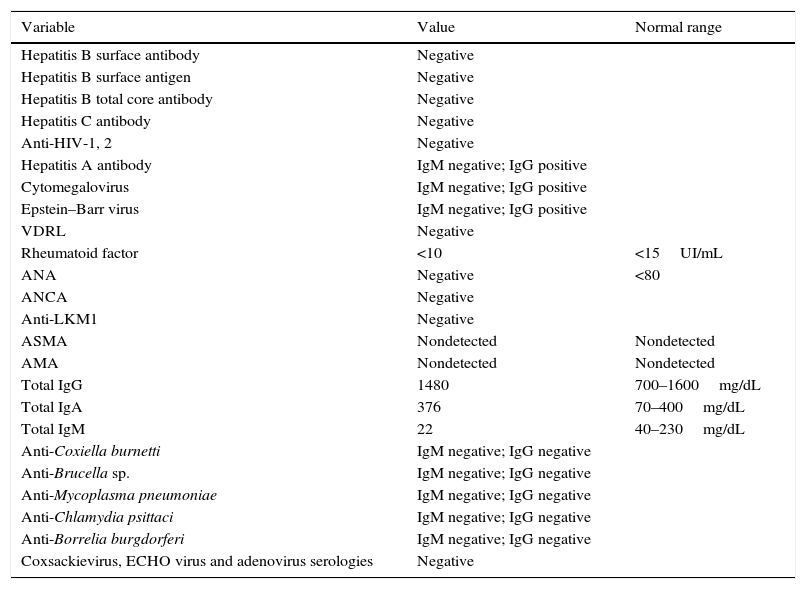

Additional workup.

| Variable | Value | Normal range |

|---|---|---|

| Hepatitis B surface antibody | Negative | |

| Hepatitis B surface antigen | Negative | |

| Hepatitis B total core antibody | Negative | |

| Hepatitis C antibody | Negative | |

| Anti-HIV-1, 2 | Negative | |

| Hepatitis A antibody | IgM negative; IgG positive | |

| Cytomegalovirus | IgM negative; IgG positive | |

| Epstein–Barr virus | IgM negative; IgG positive | |

| VDRL | Negative | |

| Rheumatoid factor | <10 | <15UI/mL |

| ANA | Negative | <80 |

| ANCA | Negative | |

| Anti-LKM1 | Negative | |

| ASMA | Nondetected | Nondetected |

| AMA | Nondetected | Nondetected |

| Total IgG | 1480 | 700–1600mg/dL |

| Total IgA | 376 | 70–400mg/dL |

| Total IgM | 22 | 40–230mg/dL |

| Anti-Coxiella burnetti | IgM negative; IgG negative | |

| Anti-Brucella sp. | IgM negative; IgG negative | |

| Anti-Mycoplasma pneumoniae | IgM negative; IgG negative | |

| Anti-Chlamydia psittaci | IgM negative; IgG negative | |

| Anti-Borrelia burgdorferi | IgM negative; IgG negative | |

| Coxsackievirus, ECHO virus and adenovirus serologies | Negative |

ANA, antinuclear antibody; ANCA, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; anti-LKM1, liver–kidney-microssomal antibody; ASMA, smooth muscle antibody; AMA, mitochondrial antibody; VDRL, venereal disease research.

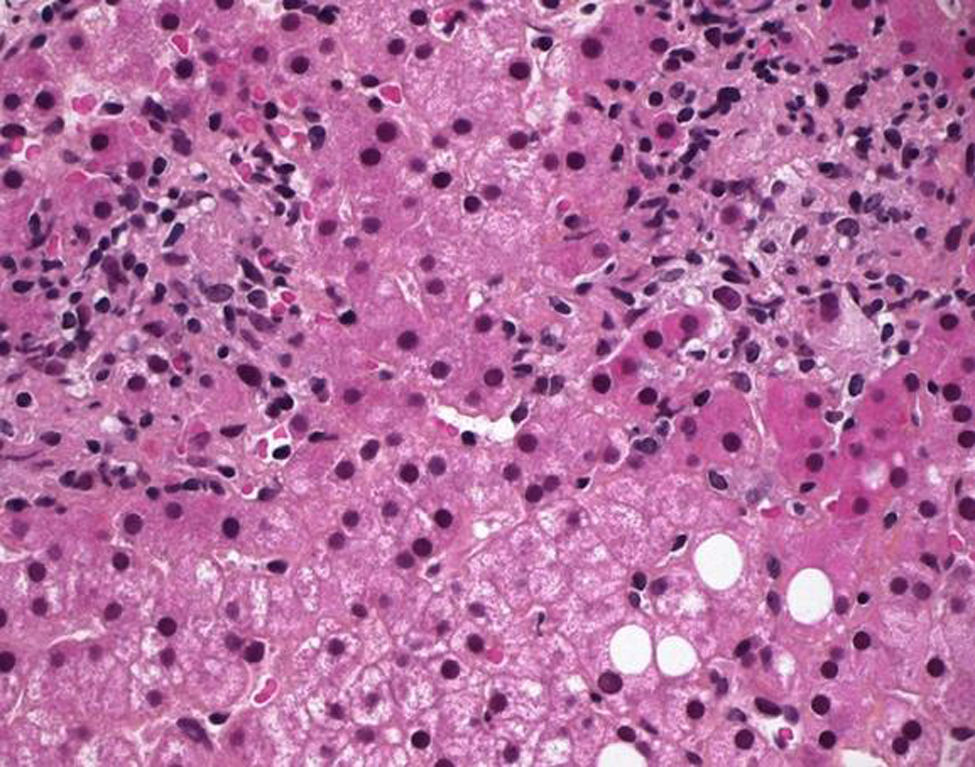

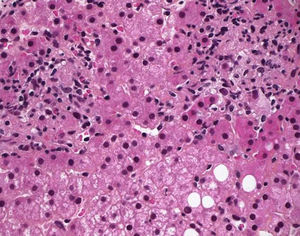

Liver biopsy was performed and histopathological examination (Fig. 4) showed a diffuse and predominantly mononuclear cell infiltrate and epithelioid granulomas with central caseating necrosis suggestive of granulomatous hepatic inflammation of tuberculous etiology. The surrounding liver parenchyma showed lymphocytic infiltration within the portal tracts. There were no fungal organisms or evidence of malignancy and although Ziehl–Neelsen staining found no acid-fast bacilli and culture of the liver specimen did not grow any microorganisms, these findings were consistent with hepatic tuberculosis.

The patient was treated with a combination of antituberculous therapy (isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide for 2 months and rifampicin and isoniazid for 7 months) and corticosteroids (prednisolone 60mg daily), tapered over 6–8 weeks. Within a few days, the fever disappeared, the patient was discharged and a steady progressive improvement of his general condition was observed. Thirty days after the beginning of treatment, there was no hepatomegaly, laboratory tests were normal, and the patient had gained weight (4kg). Three months after treatment was started, there were no abnormalities on the X-ray and the echocardiogram showed minimal pericardial effusion with no evidence of constrictive pericarditis and good global cardiac function.

One year after the completion of treatment the patient remained completely asymptomatic.

3DiscussionTuberculosis (TB) is a chronic infectious disease caused by M. tuberculosis and may invade all organs but mainly affect the lungs. The clinical presentation of TB is variable with symptoms reflecting the underlying organ involved. It frequently presents as a non-specific constitutional syndrome, with systemic manifestations, which can sometimes result in a diagnostic dilemma.

In our case, the detailed clinical assessment and extensive investigations eventually led to the diagnosis of hepatic tuberculosis associated with constrictive pericarditis and left pleural effusion. This is a very unusual presentation of a disease in which the correct diagnosis was achieved after performance of a liver biopsy.

Hepatic tuberculosis is rare7 and constitutes less than 1% of all cases of this infection.4 Hence the clinical misdiagnosis rate is high because of lack of specific clinical manifestations and imaging features.7 The presenting symptoms are usually nonspecific and are mainly constitutional in nature, including fever, night sweats, malaise, anorexia, weight loss, and abdominal pain,4 all those were present in our case. Hepatomegaly is the main sign, present in more than half of patients7 and is usually found with an increase in liver tests.8 These findings however are not specific and may occur in other conditions, such as metastatic carcinoma, liver abscess, echinococcosis, amyloidosis and granulomatous diseases of varying etiologies.9 Aminotransferases and serum bilirubin can be moderately elevated or normal while alkaline phosphatase and gamma glutamyl-transpeptidase levels are sometimes markedly raised.9 Abnormal prothrombin time has been a common finding in some series.9 Non-specific laboratory alterations, such as anemia, leukocytosis and increased erythrocyte sedimentation rates are common.9 All these laboratory abnormalities were observed in our case study.

Diagnosis of disseminated tuberculosis can be confirmed by histopathology of a tissue sample as in our case; although there were involvement of three organs, liver biopsy through needle aspiration was considered most feasible. It is of great importance in finding pathological lesions timely to make the diagnosis, in order to give effective treatment as early as possible to improve the cure rate of TB and to reduce the germination of drug-resistant tuberculosis.10 Liver is a common site for granuloma formation owing to its rich blood supply, lying at the distal end of portal circulation and large number of reticuloendothelial cells.7 In histopathology, finding hepatic granuloma with central caseating necrosis is characteristic and should be considered diagnostic of tuberculosis until proven otherwise.11

The majority of granulomas are usually located near the portal tract and there is only mild perturbation of hepatic function, so most patients are minimally symptomatic or asymptomatic.10 In autopsy series of disseminated tuberculosis, liver involvement was found in 80–100% of the cases.12

In our patient there were no signs of lung disease. However, there was a small left pleural effusion and the development of a characteristic pleuritic pain, indicating this as another site of the disease. Pleural tuberculosis is the second more frequent site of extrapulmonary TB after lymph node involvement.13 Although pleural TB infection is thought to result from the rupture of a subpleural caseous focus within the lung into the pleural space, it may occasionally be a result of hematogenous dissemination or contamination from adjacent infected lymph nodes.13

Pericardial involvement most commonly results from direct extension of infection from adjacent mediastinal lymph nodes, or through lympho-hematogenous route from a focus elsewhere and patients who have tuberculous pericarditis usually have a focus of infection elsewhere.15 The mortality rate in untreated acute effusive TB pericarditis approaches 85%.5 The onset may be abrupt or insidious with symptoms such as chest pain, dyspnea, and ankle edema. Cardiomegaly, tachycardia, fever, pericardial rub, pulsus paradoxus, or distended neck veins may be found on examination.15 Viral infections, especially coxsackievirus B and echovirus 8, may cause pericarditis with clinical features that cannot be distinguished from idiopathic pericarditis. Symptoms of our patient associated with hepatomegaly and histological findings, however, would be unusual in a benign viral infection.5 The presence of pericardium involvement and the fact there was no sign of lung involvement made the diagnosis of sarcoidosis unlikely. On the other hand, the absence of epidemiologic features and cardiac valvulopathy made the diagnosis of brucellosis and Q fever less likely.

Risk factors for TB are related to host's compromised immune system and include HIV infection, diabetes mellitus, smoking and alcohol abuse.13 Disseminated tuberculosis (TB) is even rarer in the immunocompetent host and the only risk factor present in our patient was the history of alcohol abuse.

The tuberculin skin test is of little value as a diagnostic method, once other conditions can be associated with a positive reaction, and this test may be negative specially in patients with extrapulmonary tuberculosis.5 More accurate interferon gamma release assays (IGRAs) detect T-cells specific for M. tuberculosis antigen.5 Although an indirect test for tuberculosis infection (including infection resulting in active disease), it is approved and of significant importance when used in conjunction with high clinical suspicion, radiography and other medical and diagnostic evaluations suggestive of TB disease.14

Sometimes, clinical diagnosis of tuberculosis is confirmed only after complete recovery due to antituberculous therapy.5 The patient's low-grade fever, loss of appetite, hepatomegaly and the laboratory data that suggest a chronic inflammatory or infectious process, together with the presence of epithelioid granulomas in liver biopsy, pleural effusion and signs of constrictive pericarditis on CT and echocardiography, pointed toward tuberculosis as the main diagnosis. The absence of lymphadenopathy and no blood morphologic abnormalities in a case with systemic involvement ruled out the suspicion of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Anti-TB treatment is effective in most of cases and can minimize morbidity and mortality but may need to be initiated empirically. A negative smear for acid-fast bacillus and failure to culture M. tuberculosis do not exclude the diagnosis.15 Adjunctive corticosteroids may be beneficial in patients with tuberculous meningitis, tuberculous pericarditis, or miliary tuberculosis with refractory hypoxemia,15 as it might be associated with fewer deaths, less frequent need for pericardiocentesis or pericardiectomy.5

A 6- to 9-month regimen (2 months of isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol, followed by 4–7 months of isoniazid and rifampin) is recommended as initial therapy for all forms of extrapulmonary tuberculosis unless the organisms are known or strongly suspected to be resistant to the first-line drugs.15

4ConclusionExtrapulmonary TB lacks typical clinical symptoms and imaging diagnosis, so can easily be misdiagnosed and treatment delayed. The hallmark of disseminated and extrapulmonary TB histopathology is the epithelioid granuloma with central caseating necrosis and the diagnosis is based on finding acid-fast bacilli in a smear or culture and/or the presence of caseous granulomas in a tissue specimen. However, rarely, if ever, are any TB bacilli seen. A high degree of clinical suspicion is required to diagnose this entity which can be medically managed easily but if not treated can lead to death.

Therefore, tuberculosis of the liver should be considered in any case of unexplained hepatomegaly and fever of unknown origin; and, in suspicious cases, a liver biopsy can be the key to diagnosing the disease and should be performed without delay, since this condition responds well to early treatment.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.