Background/Objective: Increased life expectancy has made quality of life the primary objective in the care of chronic patients and people living with HIV. It found evidence of the link between optimism, quality of life and well-being. This article aimed to determine whether affectivity in its two dimensions (positive and negative) played a mediating role in the association between optimism and quality of life in men living with HIV. Method: 116 men living with HIV (the average age was 36.8 years (SD=9.06), and the average time from the diagnosis was 8.2 years) responded to three instruments: Life Orientation Test revised version (LOT-R), the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) and the World Health Organization Quality of Life-Bref (WHOQoL-Bref). Results: The results showed that positive affect had no mediating effect, whereas negative affect mediated the relation of optimism with two quality-of-life dimensions (overall quality of life and environment). Conclusion: In conclusion, negative affect was found to participate only partially, acting as a mediating variable.

Antecedente/Objetivos: El aumento de la esperanza de vida ha hecho de la calidad de vida (CV) el objetivo fundamental en el cuidado de pacientes crónicos y en personas que viven con VIH. Se ha encontrado evidencia del vínculo entre optimismo, calidad de vida y bienestar. El propósito del presente estudio fue determinar si la afectividad en sus dos dimensiones (positiva y negativa) desempeña un rol mediador en la asociación entre optimismo y calidad de vida en hombres viviendo con VIH que tienen sexo con hombres. Método: Cientodieciséis hombres con VIH (edad promedio fue de 36,8 años; DT = 9,06; tiempo medio desde el diagnóstico de 8,2 años) contestaron tres instrumentos: Life Orientation Test Revised Version (LOT-R), Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) y World Health Organization Quality of Life-Bref (WHOQoL-Bref). Resultados: Los resultados mostraron que el afecto positivo no tuvo efecto mediador, mientras el afecto negativo medió la relación entre optimismo y dos dimensiones de la calidad de vida (calidad de vida general y ambiente). Conclusiones: Se encontró que el afecto negativo participa parcialmente como una variable mediadora entre el optimismo y calidad de vida.

Thanks to the current availability of highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART), HIV/Aids has been “transformed from a progressive fatal disease to a manageable chronic disease” (Mrus et al., 2006, p. S39). The development of HAART has managed to extend longevity, among others benefits (Harrison, Song, & Zhang, 2010; Nakagawa et al., 2012). This increase in life expectancy has made quality of life (QL) the fundamental aim in the care of chronic patients. The term quality of life is used in numerous contexts and is perceived as a character trait, attitude or response to an emotional stimulus. It is associated with activities that promote health, a positive attitude toward life and satisfaction with life (Mukolo & Wallston, 2012; Szramka-Pawlak et al., 2014). According to WHO guidelines, any reference to QL must include a person's physical and mental state, social relationships, environment, religion, beliefs and opinions, including positive and negative feelings (Kreis et al., 2015).

Research has shown that QL is lower in people living with HIV than with other chronic diseases (Stutterheim et al., 2012). Studies into the behavioral and psycho-social dimensions of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) have shown that low levels in a person's QL are the cause of poor outcomes in the prognosis and treatment of the disease (Mukolo & Wallston, 2012). Recent investigations have also referred to a strong link between depressive states and perceived stress in people with HIV and adherence to antiretroviral treatment (ART), commitment to the prevention of infection by HIV and the person'sQL in general (Ballester-Arnal et al., 2016; Mukolo & Wallston, 2012).

At the moment there is a perception that positive thought leads to an improvement in both mental and physical health (Chaves, Vazquez, & Hervas, 2013; Fernandes de Araujo, Teva, & Bermúdez, 2015; López, 2015; Park, Peterson, & Sun, 2013). Studies in the field of psychology have described how some positive emotional capacities in individuals make them better able to adapt to stress factors. Adaptive coping would lead to a sensation of well-being and better perception of QL, whereas mal adaptation would be associated with greater states of distress or depression (Ballester-Arnal et al., 2016; Mukolo & Wallston, 2012).

One of the positive psychological resourcesis optimism, defined as the generalized and stable expectation that one's own life will see good and not bad results (Gázquez Linares, Pérez Fuentes, Mercader Rubio, & Inglés Saura, 2014; Londoño, Velasco, Alejo, Botero, & Vanegas, 2014; Scheier & Carver, 1985; Szramka-Pawlak et al., 2014). Several studies have endeavored to ascertain the relationship between optimism and QL, and an important correlation has been reported (Carver, Scheier, & Segerstrom, 2010; Mannix, Feldman, & Moody, 2009), which may be explained by the expectations or general cognitions of a good prognosis for the future that optimistic people exhibit, which would impact on their perception of QL. In the area of health, most studies have been conducted with people with cancer, epilepsy, hemodialysis and with patients who have had a coronary bypass, and it was observed in all these cases that the people with higher optimism levels have desirable, positive and viable expectations in terms of the prognosis or treatment of their disease, which they continue by extending their efforts to heal, even when this implies a difficult or painful process (Kreis et al., 2015).

There has been less development in studies that assess the relationship between optimism and QL in people who suffer from HIV. These studies have observed mainly a positive link between optimism and QL, where people with an optimistic attitude have a better perception of health and well-being and fewer depressive symptoms (Brydon, Walker, Wawrzyniak, Chart, & Steptoe, 2009; Ironson & Hayward, 2008; Mukolo & Wallston, 2012; Wagner, Hilker, Hepworth, & Wallston, 2010). In theoretical terms, positive psychological attributes, such as optimism, may make it easier to deal with stress factors and minimize the inappropriate behaviors that could affect the course and treatment of a chronic health condition like HIV (Mukolo & Wallston, 2012).

The study of positive and negative affects has also increased in recent years. Watson, Clark and Carey (1988) warned that although these denominations may suggest they are polar opposites of the same dimension, positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA) are highly distinctive dimensions that can be represented as orthogonal factors. It has been suggested that PA improves health because it has been associated with better health practices and a lower risk of premature death (Dockray & Steptoe, 2010). While negative thought reduces cerebral coordination, hampering thought processes and problem solving (Aubele, Wenck, & Reynolds, 2011). There is considerable evidence that psychological states with a greater presence of NA are related to bad health and a poor adjustment to disease (Morris, Yelin, Panopalis, Julian, & Katz, 2011), including HIV(Mukolo & Wallston, 2012; Schuster, Bornovalova, & Hunt, 2012).

Therefore, affectivity can have negative but also positive effects on health. This combined with the linking of affectivity to cognitive processes could have an influence on the perception of QL (McCabe, Firth, & O¿Connor, 2009; Pérez-San-Gregorio et al., 2012; Vera-Villarroel & Celis-Atenas, 2014). There are studies that have reported a positive correlation between PA and QL in chronic diseases (Mazzoni & Cicognani, 2011; Quiceno & Vinaccia, 2014; Urzúa & Caqueo-Urízar, 2012; Urzúa et al., 2015), as well as a negative correlation between NA and QL in HIV (Mrus et al., 2006; Reis et al., 2011).

But positive and negative affects might also play a mediating role (Vera-Villarroel, Urzúa, Pavez, Celis-Atenas, & Silva, 2012), which has been evaluated in studies that considered optimism as a predictive variable, and health results (Baker, 2007; Lench, 2010; Mera & Ortiz, 2012), stress and self-efficacy (Schönfeld, Brailovskaia, Bieda, Zhang, & Margraf, 2016), happiness, health, and subjective sexual well-being (Contreras, Lillo, & Vera-Villarroel, 2016) or satisfaction with life (Chang, Sanna, & Yang, 2003; Vera-Villarroel & Celis-Atenas, 2014; Vera-Villarroel et al., 2012) as criterion variables among the student population, but not among the diseased population and even less so among patients with HIV. Ammirati, Lamis, Campos and Farber (2015) found that optimism was positively associated with psychological well-being and psychological well-being was negatively associated with the stigma associated with HIV. It has also been found the environmental well-being and mental health are the main predictors of subjective well-being in among people living with HIV (Oberje, Dima, van Hulzen, Prins, & de Bruin, 2015). It also remains to be clarified that both PA and NA, being independent factors, might present differences in their relation to QL, which has usually not been considered in investigations dealing with their impact on health outcomes.

Bearing this in mind, the aim of this study was: (a) to evaluate the existing relation between optimism and QL in people living with HIV; (b) to determine if both PA and NA act as mediators; and (c) to evaluate if there are differences determined by the two types of affect based on their relation with the other variables and on their mediating role.

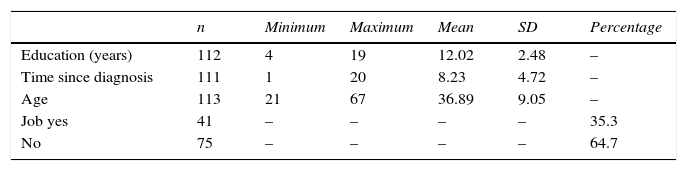

MethodParticipantsThe sample was non-probabilistic or haphazard. We chose this alternative based on Chile's legal and institutional framework that ensures strict confidentiality, being AIDS a condition that produces discrimination and stigmatization (Ferrer, 2008). Therefore, the researchers only worked with groups and individuals that voluntarily agreed to collaborate in this project. The sample was comprised of 116 men who have sex with men living with HIV belonging to different groups from the city of Santiago, Chile. Table 1 presents the characteristics of the sample. The main data show that the average age was 36.8 years (SD=9.06), and the average time from the diagnosis was 8.2 years (SD= 4.72).

Instruments- –

Adhoc survey of demographic variables. Personal questions regarding age, sexual orientation, education (years), period of infection (years), and job were included.

- –

Life Orientation Test Revised Version (LOT-R) (Cano-García et al., 2015; Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 1994). The LOT-R consists of 10 items, where the participants indicate their level of agreement with each question on a 5-point scale, from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”(Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 2001). It has 4 “filler” items that serve to make less evident the content of the test. Realiability was assessed with a Cronbach's alpha of .51. There is a Chilean validation with a reliability of α= .65, and in terms of the construct validity, the exploratory factor analysis revealed two factors related to two of their dimensions, a model that explained 55.55% of the variance (Vera-Villarroel, Córdova-Rubio, & Celis-Atenas, 2009).

- –

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). Created by Watson, Clark and Tellegen (1988), it contains two affectivity dimensions: NA and PA. A validation was conducted in Chile by Dufey and Fernández (2012) in which adequate reliability indices were obtained as well as an adequate internal validity. It consists of 40 adjectives that describe the emotional state, which are assigned a punctuation ranging from 1 (nothing or almost nothing) to 5 (a lot). It comprises two dimensions: Negative affect which is defined as a general factor of subjective distress that includes a wide variety of negative moods, including fear, anxiety, hostility, disgust, loneliness and sadness. The other dimension is Positive affect which refer to pleasant sentiments in relation to the environment. The PANAS is characterized by a high internal consistency, with alphas of .86 to .90 for Positive affect and .84 to .87 for Negative affect, the correlation between the two affections is invariably low, ranging from -0.12 to -0.23. In the present shows a Cronbach's alpha of .71 and .82 for the Positive and Negative Affective respectively was obtained.

- –

World Health Organization Quality of Life-Bref (WHOQOL-Bref). Developed by the WHOQoL Group (1996), of its 26 questions, two are general on the overall rating of QL (item 1) and satisfaction with health (item 2). The other 24 questions are a multidimensional rating of QL grouped into four areas that evaluate Physical Health, Psychological Health, Social Relations, and Environment. These studies usually base their analyses on the four domains of the questionnaire; however, some studies have also considered general indicators (Lai, Chen, Chen, Chen, & Wang, 2006). The internal consistency of the scale is α=.98 (The WHOQoL Group, 1996). Urzúa (2008) applied the instrument to the Chilean population, reporting an internal consistency (from .69 to .77).

Several support groups for people living with HIV/Aids were contacted, of which four gave their approval to work with their members. To protect anonymity, the instruments contained only a code instead of a name. Three organizations participated, all of them community based organizations (CBOs). Participants signed an informed consent form in which the purpose of the investigation, procedure and rights were specified. After the form was signed, the participants completed the questionnaires. The study was part of a larger project on wellbeing funded by two government offices (The Chilean Ministry of Education and the National Commission of Science and Technology). As such, it followed the standards of the Chilean scientific research, being approved by the ethics boards of Fondecyt and the Universidad de Santiago de Chile-USACH.

Data analysisDescriptive analysis. In order to know the behavior of each of the variables: optimism, affection, and quality of life, and demographic variables: age, schooling, years living with illness and employment. This was obtained by computing means and standard deviations of the different scales or using frequencies for the case of qualitative variables like employment.

Correlation Analysis. It was determined whether the expected associations between the variable (as proposed) predictor with the (proposed as) a result, between the variable (as proposed) predictor variables and the (proposed as) mediators met; and among variables (as proposed) and mediating variables (as proposed) result. Also they took into account the demographic variables in order to determine its intervention in the previous results. Measurements were made based on the two types of correlation coefficients: biserial point for employment variable (real dichotomous) and Pearson for the rest of the variables.

Analysis of mediation. The existence of mediation of positive and negative affect was determined independently, in addition to prove the significance. Baron and Kenny (1986) causal steps methodology was used to prove the aforementioned. Three equations using regressions were performed. First, the criteria variable on the predictor to establish that there is an effect to mediate (via c). Second, the mediator on the predictor to establish via a. In the third equation, the variable criteria on both the predictor and the mediator. This provides a test of whether the mediator is related to the approach (via b) and an estimate of the relationship between the predictor and the criterion controlling the mediator (via c’). The method of Kenny, Kashy and Bolger (1998), to test the significance of the mediating effect is as follows: because the difference between the total effect of the predictor on the criterion (via c) and the direct effect of the predictor on the criterion is equal to the product of the way predictor the mediator (via a) and the mediator to the criteria (via b), the significance of the difference between channels can be evaluated by testing the significance of the products of the tracks a and b. Specifically, the product of the routes to a and b is divided by a standard error term. Sobel in 1982 proposed a test of significance for the indirect effect of the independent variable on the dependent via the mediator (z-value = a * b / SQRT (b2 * SA2 + a2 * SB2). The route of the independent variable with the mediator is “a” and its standard error is Sa, the way of the mediator to the dependent is “b” and standard error would Sb the mediating effect divided by its standard error is a z score of the mediating effect. If the z-score is greater than 1.96 the effect is significant at the .05 level.

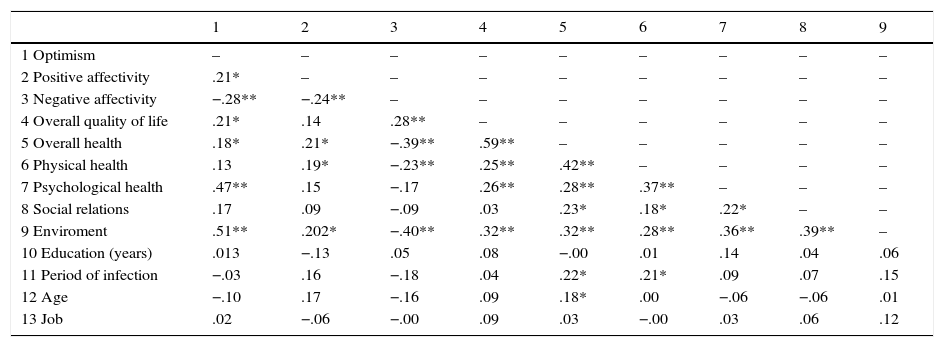

ResultsRelation between optimism, affectivity and QL. In the first analysis, it was observed that optimism was associated significantly with four of the QL sub-scales or indicators: overall quality of life (r=.21, p=.023), overall health (r=.18, p=.045), psychological health (r=.47, p=.000) and environment (r=.51, p=.000); there was no correlation with the rest: physical health (r=.13, p=.143) and social relations(r=.17, p=.061). In a second analysis, the correlations between optimism and the mediating variables were evaluated: PA and NA. The results indicated an association of the predictive variable with the mediators: PA (r=.21, p=.021), and NA (r=-.28, p=.002). A summary of the all the correlations is shown in Table 2.

Summary of variable correlation evaluated.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Optimism | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2 Positive affectivity | .21* | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 3 Negative affectivity | −.28** | −.24** | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 4 Overall quality of life | .21* | .14 | .28** | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 5 Overall health | .18* | .21* | −.39** | .59** | – | – | – | – | – |

| 6 Physical health | .13 | .19* | −.23** | .25** | .42** | – | – | – | – |

| 7 Psychological health | .47** | .15 | −.17 | .26** | .28** | .37** | – | – | – |

| 8 Social relations | .17 | .09 | −.09 | .03 | .23* | .18* | .22* | – | – |

| 9 Enviroment | .51** | .202* | −.40** | .32** | .32** | .28** | .36** | .39** | – |

| 10 Education (years) | .013 | −.13 | .05 | .08 | −.00 | .01 | .14 | .04 | .06 |

| 11 Period of infection | −.03 | .16 | −.18 | .04 | .22* | .21* | .09 | .07 | .15 |

| 12 Age | −.10 | .17 | −.16 | .09 | .18* | .00 | −.06 | −.06 | .01 |

| 13 Job | .02 | −.06 | −.00 | .09 | .03 | −.00 | .03 | .06 | .12 |

There were variables that could not be controlled a priori that might influence the analyses. Age and time of infection were controlled in the optimism-overall Health relation; once controlled, this association ceased to be significant (r=.18, p=.065), which is why it remained outside the subsequent analyses.

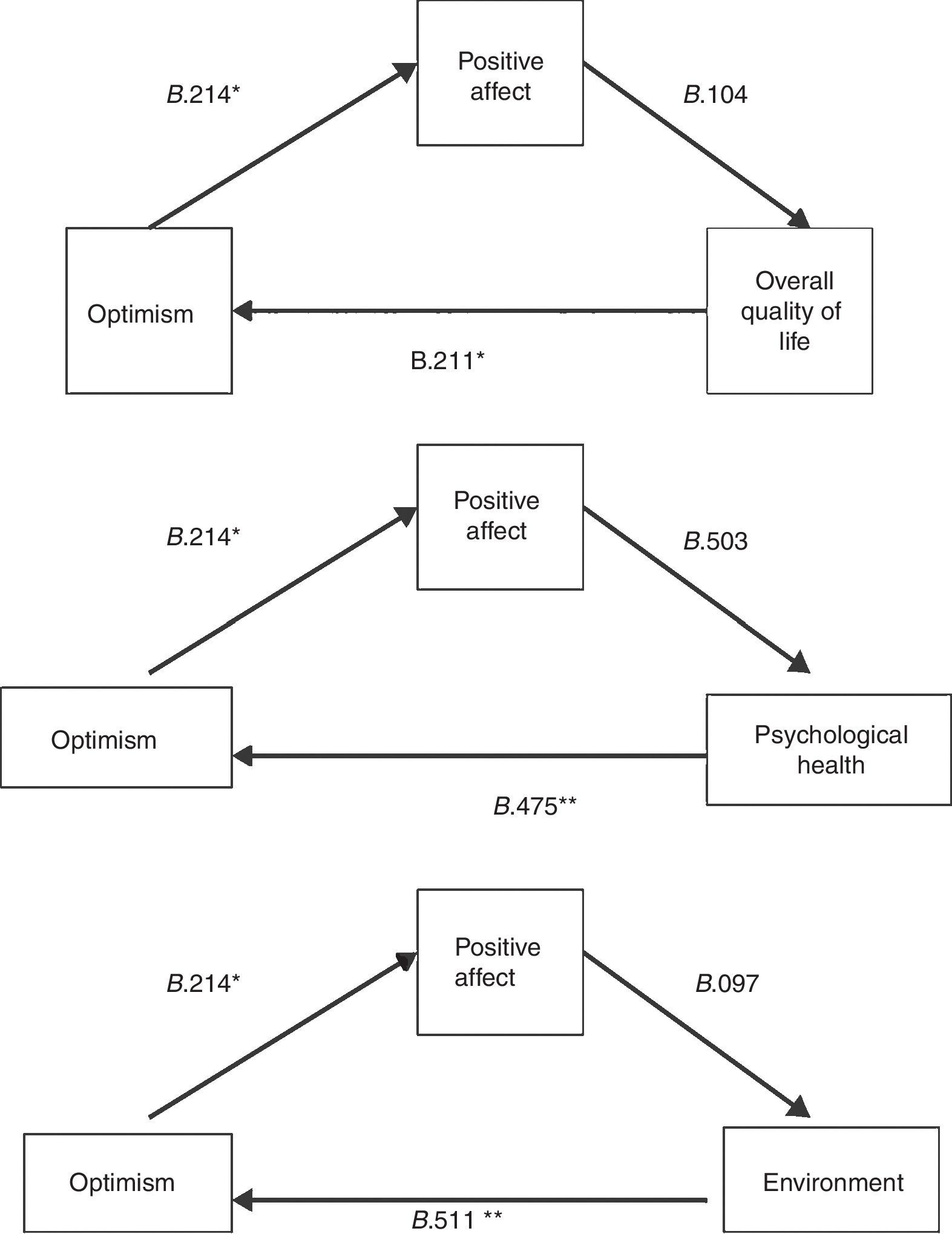

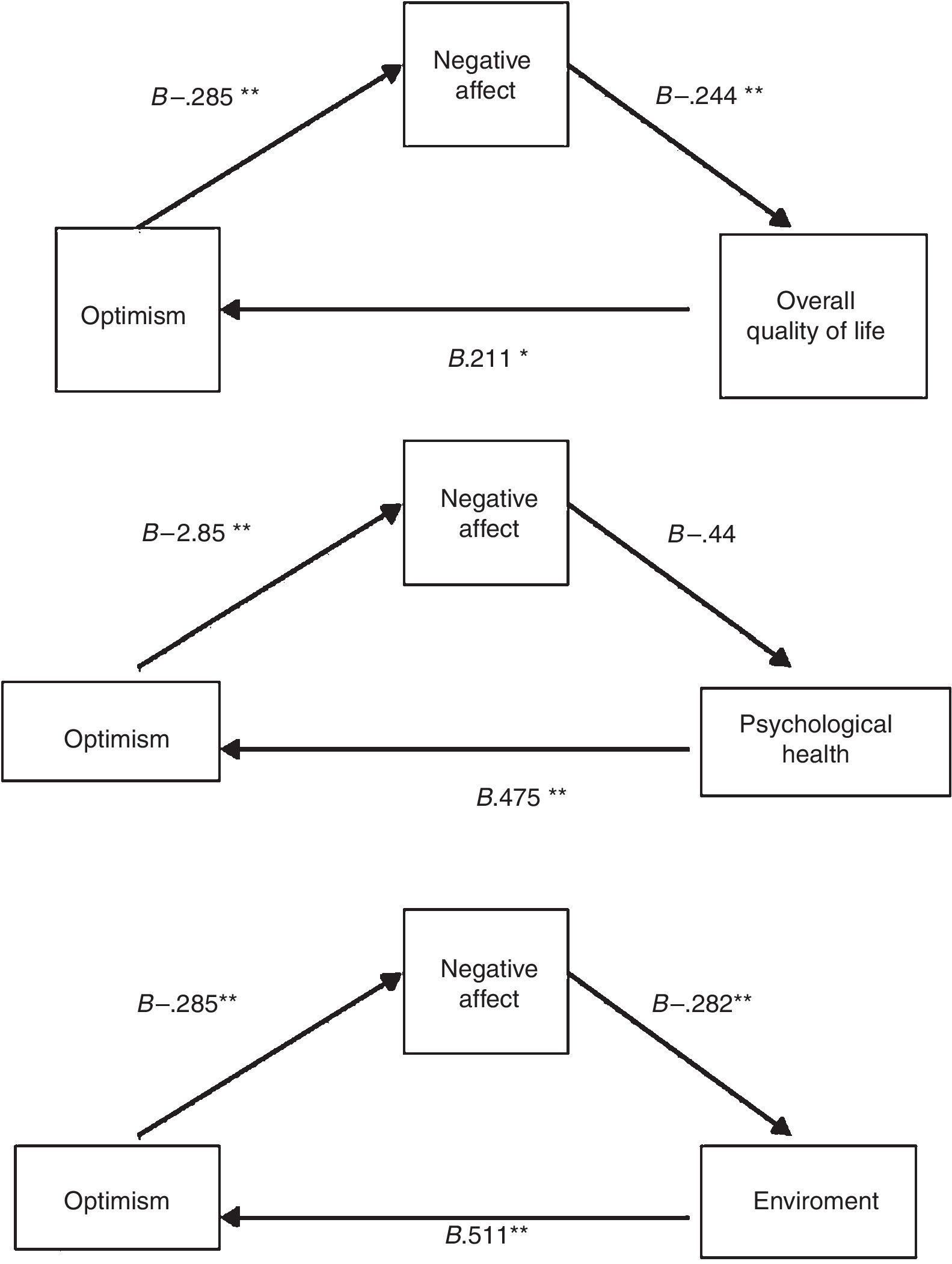

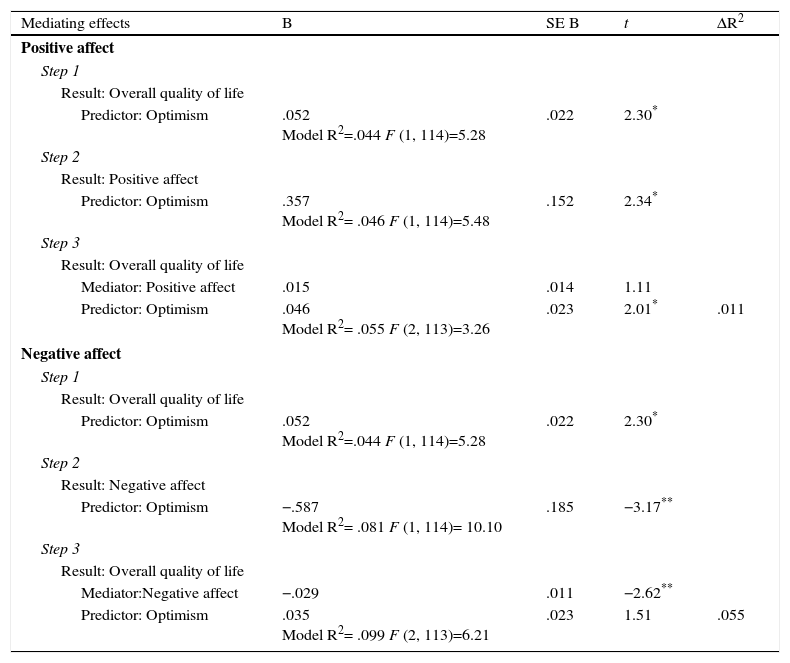

Affectivity as mediator. Table 3 contains the process with reference to the overall quality of life as a criterion variable following the causal steps proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986). Of the two mediators proposed, only NA satisfied the requirements to be able to determine mediation, there being an association between optimism and overall quality of life (β=.211; p=.023), between optimism and NA (β=-.285; p=.002), and between NA and overall quality of life (β= -.244; p=.010); however, the relation between optimism and overall quality of life when including NA decreased (β from .052 to .035) and even ceased to be significant (p=.133). By contrast, PA fulfilled the first two steps (β=.211; p=.023; β=.214; p=.021), but not the third (β=.104; p=.268).

Mediating effects on overall quality of life.

| Mediating effects | B | SE B | t | ΔR2 |

| Positive affect | ||||

| Step 1 | ||||

| Result: Overall quality of life | ||||

| Predictor: Optimism | .052 Model R2=.044 F (1, 114)=5.28 | .022 | 2.30* | |

| Step 2 | ||||

| Result: Positive affect | ||||

| Predictor: Optimism | .357 Model R2= .046 F (1, 114)=5.48 | .152 | 2.34* | |

| Step 3 | ||||

| Result: Overall quality of life | ||||

| Mediator: Positive affect | .015 | .014 | 1.11 | |

| Predictor: Optimism | .046 Model R2= .055 F (2, 113)=3.26 | .023 | 2.01* | .011 |

| Negative affect | ||||

| Step 1 | ||||

| Result: Overall quality of life | ||||

| Predictor: Optimism | .052 Model R2=.044 F (1, 114)=5.28 | .022 | 2.30* | |

| Step 2 | ||||

| Result: Negative affect | ||||

| Predictor: Optimism | −.587 Model R2= .081 F (1, 114)= 10.10 | .185 | −3.17** | |

| Step 3 | ||||

| Result: Overall quality of life | ||||

| Mediator:Negative affect | −.029 | .011 | −2.62** | |

| Predictor: Optimism | .035 Model R2= .099 F (2, 113)=6.21 | .023 | 1.51 | .055 |

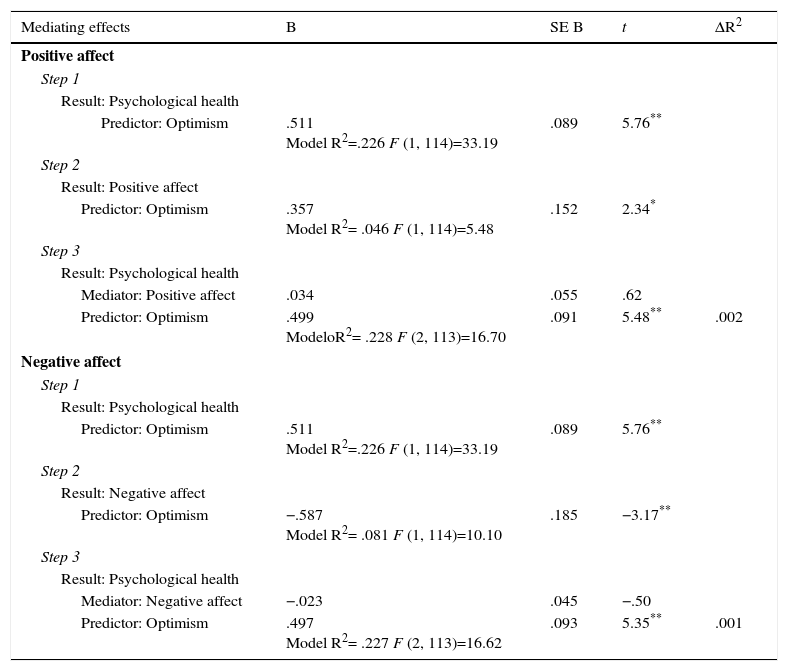

With respect to psychological health as a criterion variable (Table 4), neither PA (β=.053; p=.536) nor NA (β =-.044; p=.612) were potential mediators as they were not associated with the criterion variable.

Mediating effects on psychological health.

| Mediating effects | B | SE B | t | ΔR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive affect | ||||

| Step 1 | ||||

| Result: Psychological health | ||||

| Predictor: Optimism | .511 Model R2=.226 F (1, 114)=33.19 | .089 | 5.76** | |

| Step 2 | ||||

| Result: Positive affect | ||||

| Predictor: Optimism | .357 Model R2= .046 F (1, 114)=5.48 | .152 | 2.34* | |

| Step 3 | ||||

| Result: Psychological health | ||||

| Mediator: Positive affect | .034 | .055 | .62 | |

| Predictor: Optimism | .499 ModeloR2= .228 F (2, 113)=16.70 | .091 | 5.48** | .002 |

| Negative affect | ||||

| Step 1 | ||||

| Result: Psychological health | ||||

| Predictor: Optimism | .511 Model R2=.226 F (1, 114)=33.19 | .089 | 5.76** | |

| Step 2 | ||||

| Result: Negative affect | ||||

| Predictor: Optimism | −.587 Model R2= .081 F (1, 114)=10.10 | .185 | −3.17** | |

| Step 3 | ||||

| Result: Psychological health | ||||

| Mediator: Negative affect | −.023 | .045 | −.50 | |

| Predictor: Optimism | .497 Model R2= .227 F (2, 113)=16.62 | .093 | 5.35** | .001 |

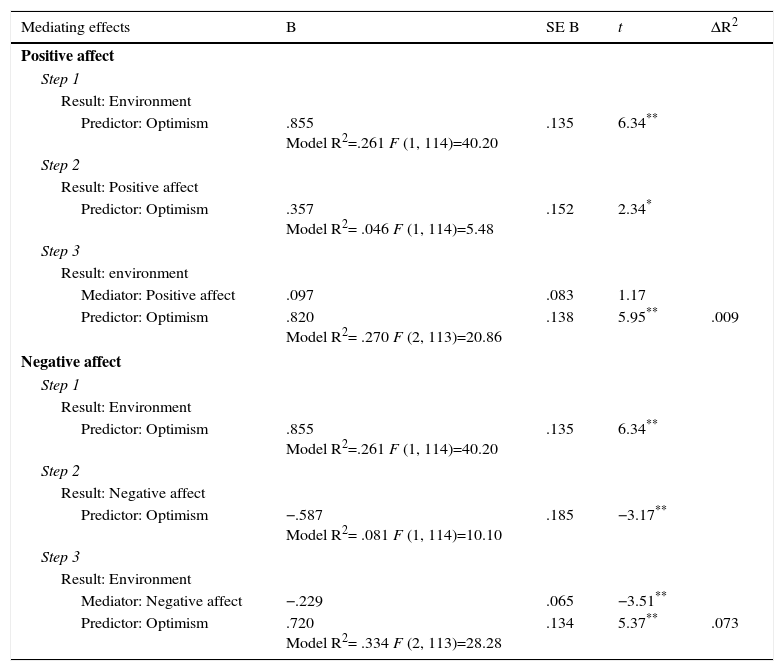

Finally, the mediation analyses for the third variable proposed as a criterion (environment) are summarized in Table 5. This time, PA had no mediating role as it did not fulfill step three (β=.097; p=.242), whereas NA fulfilled the mediation requirements. There was an association between optimism and environment (β=.511; p=.000), between optimism and NA (β =-.285; p=.002), between NA and environment (β =-.282; p=.001), and between optimism and environment when adding NA (β=.430; p=.000); however, this association decreased due to this inclusion (ß from .85 to .72).

Mediating effects on the environment.

| Mediating effects | B | SE B | t | ΔR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive affect | ||||

| Step 1 | ||||

| Result: Environment | ||||

| Predictor: Optimism | .855 Model R2=.261 F (1, 114)=40.20 | .135 | 6.34** | |

| Step 2 | ||||

| Result: Positive affect | ||||

| Predictor: Optimism | .357 Model R2= .046 F (1, 114)=5.48 | .152 | 2.34* | |

| Step 3 | ||||

| Result: environment | ||||

| Mediator: Positive affect | .097 | .083 | 1.17 | |

| Predictor: Optimism | .820 Model R2= .270 F (2, 113)=20.86 | .138 | 5.95** | .009 |

| Negative affect | ||||

| Step 1 | ||||

| Result: Environment | ||||

| Predictor: Optimism | .855 Model R2=.261 F (1, 114)=40.20 | .135 | 6.34** | |

| Step 2 | ||||

| Result: Negative affect | ||||

| Predictor: Optimism | −.587 Model R2= .081 F (1, 114)=10.10 | .185 | −3.17** | |

| Step 3 | ||||

| Result: Environment | ||||

| Mediator: Negative affect | −.229 | .065 | −3.51** | |

| Predictor: Optimism | .720 Model R2= .334 F (2, 113)=28.28 | .134 | 5.37** | .073 |

The results showed the existence of two mediation options (Figures 1 and 2), and in order to determine whether they were significant, a z point score was obtained using Sobel's test. The two options were significant: 1) NA was a significant mediator of the optimism-overall quality of life relation (z=2.02; p=.043), mediating 33.09% of this relation. NA was again a significant mediator, this time of the optimism-environment relation (z=2.35; p=.018), mediating 15.73% of the relation. Causal steps of Baron and Kenny (1986) were followed. In both cases the z scores was superior to 1.96. As the result in the mediation scores was not zero, a partial mediation was assumed.

DiscussionThis study sought to ascertain whether affectivity played a mediating role in the association between optimism and QL. Optimism was associated with the variables proposed as mediators, which is consistent with the literature both in relation to PA (Marshall, Wortman, Kuslas, Hervig, & Vickers, 1992) and NA (Ben-Zur, 2003; Yan & Wong, 2011). Moreover, it was determined that optimism was partially associated with QL (overall quality of life, psychological health and environment).

The lack of correlation between optimism and the other QL dimensions such as overall health and physical health are not consistent with most of the studies that have found a strong association between optimism and health (Rasmussen,Wrosch, Scheier, & Carver, 2006) even with HIV (Ironson & Hayward, 2008). Likewise, the correlation with social relations was not expected, given that such this dimension is very similar to social support, which is known to be associated with optimism (Bastardo & Kimberlin, 2000). Directly related to the aim, it was discovered that PA did not mediate any of the associations of optimism with the QL dimensions, and that NA participated more in mediating the relation between optimism and two of the QL domains (overall quality of life and environment).

What is new is that as far as the mediating role of the affect is concerned, NA alone turned out to be significant, considering that there are studies that have evaluated the two affects, with both being mediators of the optimism-satisfaction with life relation in another type of population (Chang et al., 2003). Possible explanations might refer to Lench (2010), who mentioned that negative emotions seem to be particularly detrimental to mental and physical health. Another reason is the possible involvement of stress, since this variable has been linked to NA but not to PA (Clark & Watson, 1986), and it is also well known that it is common to find stress in chronic diseases (Christensen, Turner, Smith, Holman, & Gregory, 1991) including HIV (Piña, Sánchez-Sosa, Fierros, Ybarra, & Cázeres, 2011). Finally it must be consider that certain positive variables including optimism operates relatively according to the context and sample (McNulty & Finchman, 2012) occasionally resulting in the opposite way.

The results of the present study provide evidence of the need to design intervention programs for patients with HIV (Fernandes de Araujo, Teva, & Bermúdez, 2014) aimed at increasing optimism and reducing NA so as to improve QL. Although optimistic thinking can be difficult to change (Ironson & Hayward, 2008), there are studies that have tried to increase their levels through interventions centered on stress and coping.

The results presented here might support the premise that people sometimes have patterns of negative mental distortions that promote NA and lead the person to stop trying to reach their goals. In this sense, cognitive-behavioral interventions, in addition to promoting an increase in optimism levels, also have an impact on the reduction of NA, which has proven to be effective in people living with HIV compared to control groups (Carrico et al., 2006; Yu et al., 2014).

In addition, the results of this study contribute evidence in the area of clinical practice for the design of customized treatment plans. Specifically our results underscore the importance of optimism in improving QL in people living with HIV, which can be integrated into both individual and group treatments and intervention guidelines. This influence could also be enhanced by intervention at the level of positive and/or negative affects. This evidence reinforces the need to develop and improve emotional cognitive strategies in the management of the related affects in people who live with HIV. Thus, the effects of optimism on well-being and the immune system for which there is already evidence could be boosted even more by explicitly incorporating affects and optimism in quality of life interventions.

This study does have some limitations. First is the reliability index of the instrument used to evaluate optimism (α=.51). This implicate that the internal reliability in this sample is low which was unexpected considering that there is a validation of this test in a Chilean sample, although not in a population with a chronic disease. According with George and Mallery (2003) criteria, it is still acceptable. Future studies should consider to improve this or other instruments to use specifically in populations with chronic diseases.

Second is the sample size, since a larger sample would allow for greater accuracy and evaluation of the results. Another limitation is related to the type of design (cross-section), because in longitudinal designs, optimism has shown variations (see McNulty & Finchman, 2012).

Finally, it must be mentioned that although the primary focus has commonly been the role of NA (Hofer et al., 2005), thereby neglecting the role of PA (Denollet et al., 2008), it would not be advisable to focus solely on PA either, particularly given the results of this study. Both aspects (negative and positive) must be included in order to have the fullest picture of the situation that people are experiencing (Pelechano, González-Leandro, García, & Morán, 2013).

Specifically what this study suggests is the importance of considering positive and negative aspects in the health-disease processes of people with HIV, but at the same time there is a need to analyze and explain how are health-related.

FundingProject FONDECYT Regular N° 1140211.