Background/Objective: Although measurement instruments for intimate partner violence (IPV) are available, their validity considering the interdependence of victimization and perpetration self-reports based on dyadic reports has not been tested. The aim was to test the validity and reliability of a new version of the Dating Violence Questionnaire (DVQ–R) that includes the interdependence of victimization and perpetration self-reports using current couple information. Method: Participants were young adults comprising 616 current heterosexual couples. Each dyad member responded to the victimization and perpetration versions of the DVQ-R independently from their partner. Results: The victimization-perpetration interdependence model based on dyadic data showed a good fit to the data and was invariant across sexes. All the factors were significantly correlated with each other and were reliable. Conclusions: The DVQ is a valid and reliable measurement instrument for the independent assessment of IPV perpetration and victimization in adolescent and young adult populations and an interdependent measure of IPV victimization and perpetration. The DVQ–VP is invariant across sexes, which makes the results obtained for males and females comparable. These results show the relevance of considering perpetration and victimization together and emphasize the necessity to be cautious regarding the excessive reliability of individual self-reported perpetration or victimization to obtain more precise knowledge.

Antecedentes/Objetivo: Aunque existen instrumentos de medida de la violencia en la pareja (IPV), no se ha evaluado su validez considerando la interdependencia entre los autoinformes de victimización y perpetración con datos diádicos. El objetivo fue evaluar la validez y fiabilidad del Cuestionario de Violencia entre Novios (CuViNo) incluyendo la interdependencia entre los autoinformes de victimización y perpetración de los miembros de parejas actuales. Método: Seiscientas dieciséis parejas heterosexuales de adultos jóvenes participaron en el estudio. Cada participante respondió de manera independiente a las versiones de victimización y perpetración del CuViNo. Resultados: El modelo de interdependencia victimización-perpetración basado en datos diádicos mostró un buen ajuste a los datos e invarianza entre sexos. Todos los factores correlacionaron significativamente y fueron fiables. Conclusiones: El CuViNo es un instrumento válido y fiable para la medición independiente de perpetración y victimización de IPV en adolescentes y adultos-jóvenes, pero también para la medición interdependiente de ambas. El CuViNo también es invariante entre sexos, lo que permite comparar los resultados de hombres y mujeres. Estos resultados muestran la relevancia de tener en cuenta la interdependencia entre victimización y perpetración, así como de cuidar la excesiva confianza en los autoinformes individuales centrados en la perpetración o la victimización a la hora de alcanzar un conocimiento preciso.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a widespread social and health problem affecting millions of people worldwide. It is necessary to consider all the potential resources, starting from the precise measure of the phenomena for primary prevention, to better understand and address IPV. Along with interviews, psychometric tests are the basic instrument used by psychologists to measure, analyze, and understand human behavior; and psychometric test are widely used in the applied research. In this regard, different measurement instruments have been developed and are available in the scientific literature to obtain an accurate measure of IPV. Some of the instruments are specifically oriented to young populations (Exner-Cortens et al., 2016a; Jennings et al., 2017; Riesgo-González et al., 2019), and the IPV among these populations is generally called dating violence (DV). Although the definitions of DV vary considerably in some cases (Duval et al., 2020; Exner-Cortens et al., 2016a; Marcos et al., 2020; Sjödin et al., 2017; Smith et al., 2015), here, DV is considered as a synonym of IPV in adolescent and young populations that are not cohabiting or married (for a similar approach, see Rodríguez-Díaz et al., 2017; Rodríguez-Franco et al., 2007, 2010, 2017).

From a primary prevention perspective, exactly estimating the prevalence of DV is pivotal not only because of its immediate effect on young people involved in the violent dyad but also because of the long-term consequences (Lin & Chiao, 2020). The probability of IPV increases when violent and abusive patterns occur in adolescent and youth couple (Exner-Cortens et al., 2017; Wincentak et al., 2017); and as mentioned above, different behavioral tests that can be used to measure IPV are available in the literature. Nevertheless, considerable variability exists across instruments. For example, López-Cepero et al. (2015) reviewed 54 behavioral instruments and observed that beyond the usual variations in the structure of the types of violence measured and that could be justified by specific aims (e.g., measuring only psychological violence), important differences were found in the inclusion of males and females and its roles. In their review, 6.25% (n = 5) of the studies only included males. Of these, 60% (n = 3) addressed males as perpetrators, and 40% (n = 2) addressed males victims. However, no study included both victimization and perpetration. Fifty percent (n = 40) of the studies only included female participants. Of these, 97.5% (n = 39) addressed females as victims, and 2.5% (n = 1) addressed females as victims and perpetrators. However, none of the studies included females only as perpetrators. Finally, 43.75% of the studies included males and females. Of These, 17.14% (n = 6) only measured perpetration, 25.71% (n = 9) only measured victimization, and 57.14% (n = 20) measured victimization and perpetration. Of the twenty studies measuring perpetration and victimization, 75% (n = 15) did not assign a specific role of perpetrator or victimization to males or females, and the other 25% (n = 5) assigned the perpetrator role to males and the victim role to females. In summary, only 18.75% (n = 15) of the studies considered the perpetration and victimization of both males and females.

As demonstrated by López-Cepero et al. (2015), the measurement of IPV using behavioral instruments generally tended to study individual self-reports of victimization or perpetration. To overcome these limitations, different measurement instruments (e.g., the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale [CTS-2] or the Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory [CADRI], among others) allow researchers to connect the perpetration and victimization reports of the same informant using analogous items for perpetration (e.g., “I slapped my partner”) and victimization (e.g., “My partner slapped me”). Nevertheless, there is a tendency to validate the perpetration and victimization scales separately and not consider the potential interdependence between perpetration and victimization self-reports. The relevance of considering DV perpetration and victimization together has been recently emphasized by different researchers (Herrero et al., 2020; Juarros-Basterretxea et al., in press; Park & Kim, 2019), indicating that higher levels of perpetration are related to levels of victimization in both males and females. Considering this, it is crucial to have available validated measurement instruments including perpetration-victimization interdependence that can be used to generate new empirical evidence by considering this potentially influential element.

The interdependence between perpetration and victimization self-reports can be attributed to different reasons or situations (Juarros-Basterretxea et al., in press), such as the mutual and bidirectional IPV found in different researches (Exner-Cortens et al., 2016a; Hadersty & Ogolsky, 2020; Rubio-Garay et al., 2017) and the consequential overlapping victim-offender characteristics of the dynamics of a violent couple in which both couple members are victims and perpetrators, the perpetration of reactive violence as retaliation or self-defense, explaining the perpetration of violence a consequence of previous victimization (Park & Kim, 2019), or the tendency to justify one's own perpetration by making levels of victimization congruent (“I battered my partner because he/she battered me”) (Herrero et al., 2020). Although the mentioned cases are different in nature, they share the necessity to consider the interdependence between perpetration and victimization self-reports to obtain a more precise understanding of DV.

To the best of our knowledge and contrary to our expectations, the validity of the victimization-perpetration model based on dyadic reports has not been tested. Therefore, the model could assume the interdependence of dyad members’ scores and test the validity of the dyadic DV measurement model.

The Dating Violence Questionnaire (DVQ, also known as CuViNo due to its Spanish name Cuestionario de Violencia entre Novios) was originally developed by Rodríguez-Franco et al. (2007) to measure IPV victimization in adolescent and young populations. This first version was composed of 42 items distributed in eight factors: Detachment (7 items), Humiliation (7 items), Coercion (6 items), Emotional punishment (3 items), Physical (5 items), Sexual (6 items), Gender-based violence (5 items), and Instrumental (3 items). Nevertheless, the original scale was considered to be too long for massive application, and a reduced version (DVQ-R) of 20 items was developed to facilitate its application (Rodríguez-Díaz et al., 2017). This alternative reduced instrument also implicates a more parsimonious model of five factors composed of four items each: Detachment, Humiliation, Coercion, Physical, and Sexual. Thus, the DVQ-R is based on the three big types of IPV of psychological (detachment, humiliation, and coercion), physical, and sexual IPV.

The DVQ model has been adapted to different countries and cultural contexts and shown good psychometric properties. Specifically, the DVQ model proposed for Spanish samples has been replicated in Spain, México and Argentina (Rodríguez-Franco et al., 2010); Bolivia (Alfaro-Urquiola, 2020); Chile (Lara & López-Cepero, 2018); Ecuador (Cherrez-Santos et al., in press); Italy (Presaghi et al., 2015); and the United States (López-Cepero et al., 2016). Despite the demonstrated validity and reliability of the DVQ-R, it was originally proposed to measure participants’ DV victimization only and thus is limited by the excessive reliability on individual reports and the focus on victimization. Based on current reports of victimization and perpetration for both members of couples, the aim of the current research was twofold. The first aim was to test the measurement models of the DVQ-R in its original version for victimization and a version for perpetration (DVQ-RP) independently, as has traditionally been conducted. The second aim was to test the measurement model based on the interdependency approach for the Dating Violence Questionnaire for Victimization and Perpetration (DVQ-VP), which assumes interdependence between members’ reports of victimization and perpetration.

MethodParticipantsThe sample was composed of 616 Spanish heterosexual couples (1,258 participants) of young adults between 18 and 26 years of age (M = 21.07, SD = 2.29). The females (M = 20.57, SD = 2.11) were younger than the males (M = 21.58, SD = 2.35) (t(1215.96)= -7.99, p ≤ .001, Hedges´ g = .45). A total of 35.5% of the participants had secondary studies, 63.1% had university studies, and only a minority of 1.2% had primary studies. A significant small association between academic level and sex was found (χ22 = 16.63, p ≤ .001, Cramer´s V = .12) with a higher proportion of females possessing university students (69%) and a higher proportion of males possessing secondary education (41.1%). The proportions of males and females who had only primary studies were similar. Only people who were engaged in an intimate relationship at the time of the assessment and his/her partner were considered for the present study. The relationship length varied from 1 month to 118 months (M = 28.49, SD = 24.71).

InstrumentsDating Violence Questionnaire-R for Victimization (DVQ-R). This instrument was used to measure dating violence victimization at the hands of the current partner. The DVQ-R is composed of 20 items measuring five different forms of dating violence victimization: physical (i.e., has beaten you), sexual (i.e., insists on touching you in ways and places that you do not like and do not want), humiliation (i.e., criticizes you, underestimates the way you are, or humiliates your self-esteem), detachment (i.e., does not recognize any responsibility regarding both of you), and coercion (i.e., has physically kept you). Each dimension was measured by four items using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (all the time).

Dating Violence Questionnaire for Perpetration (DVQ-RP): The DVQ-R items were adapted to measure aggression against one's partner (DVQ-RP). The DVQ-RP is composed of 20 items measuring five different forms of dating violence victimization: physical (i.e., you have beaten your partner), sexual (i.e., you insist on touching your partner in ways and places which she/he does not like and does not want), humiliation (i.e., you criticize your partner, underestimate the way she/he is, or humiliate her/his self-esteem), detachment (i.e., you do not recognize any responsibility regarding both of you), and coercion (i.e., you have physically kept your partner). Each of the five dimensions of dating violence aggression was measured by four items using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (all the time).

ProcedureFollowing the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki), informed consent signed by each participant was obtained before responding to the self-reports. Anonymity and confidentiality were ensured: both members of the couple responded to the questionnaires at the same time separately, and no information was given to the other member of the couple. To guarantee this anonymity, once both participants answered the questionnaire, they were kept in an envelope that was closed in front of participants. After that, the questionnaires were encoded to identify the couples (e.g., 1A and 1B). Finally, all the analyses were conducted using the complete sample and never conducted for individual responses. The researcher provided their contact information to respond to any possible discomfort or doubts associated with the study. The only inclusion criterion for sample selection was being involved in a heterosexual relationship at the time of the evaluation.

Data analysisFirst, considering the lack of representativeness regarding the nature and frequency more severe forms of DV in community samples, the potential lack of representation of the responses to item categories was analyzed using frequency analysis. To accomplish this, IBM SPSS Statistics 26 was used. Second, three confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) were conducted to test the model fit to the data of the (1) DVQ–RV, (2) DVQ–RP, and (3) combined Dating Violence Questionnaire – for Victimization and Perpetration (DVQ–VP). Although the DVQ-R demonstrated good psychometric properties in previous research (Rodríguez-Díaz et al., 2017), it never has been used in the way used by this research (both members answer the same questions, and participants also had to respond to her/his own DV perpetration). Therefore, the factor structure was also tested to ensure the replicability of the DVQ-R in this condition. The model fit to the data was measured through the chi-squared statistic (p > .05 for good fit), CFI (values ≥ .95 for good fit) and RMSEA (values ≤ .05 for good fit) (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Third, after obtaining the model that best fit the data, the configural, metric, and scalar invariance across sexes (male and female) of the DVQ–VP was tested (Putnick & Bornstein, 2016; Vandenberg & Lance, 2000). Configural invariance represents the invariance of the form of a model, and it means that the organization of the tested constructs is supported for both sexes. Metric invariance represents the contributions of the items to the latent construct, and it is obtained if these contributions are similar for both sexes. Finally, scalar invariance means that differences in the latent construct capture all mean differences in the shared variance of the items. The d Δχ2 test and its associated probability, ΔCFI, and ΔRMSEA were considered to test the invariance across groups (Rutkowski & Svetina, 2017; Svetina et al., 2019). The Mean and Variance adjusted Weighted Least Square (WLSMV) estimation was used for estimations in CFAs and multigroup analyses. Finally, the reliability of the scales was estimated by the ordinal omega. As indicated by several researchers (see, for example, Elosua & Zumbo, 2008), when the item response scale is ordinal, the reliability should be estimated based on the polychoric correlation matrix due to the tendency of coefficients based on the covariance matrix to underestimate the real reliability.

The Mplus 8.6 software (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2021) was used for the CFA, multigroup analyses and reliability estimations.

ResultsResponse frequency per item category analysisThe analysis of responses revealed a misrepresentation of the third (habitually) and fourth (all of the time) response categories. More specifically, the proportion of participants who stated they experienced at least one type of victimization habitually or all the time varied between 0.1% and 5.2%. Regarding perpetration, between 0.1% and 3.8% of the participants said that they perpetrated at least one type of aggression habitually or all the time. Considering that the second response option was frequently and these results, the responses of the second, third and fourth categories were grouped into three response categories: 0 for never, 1 for sometimes, and 2 for frequently. These are indicative of a frequency-based increase in severity.

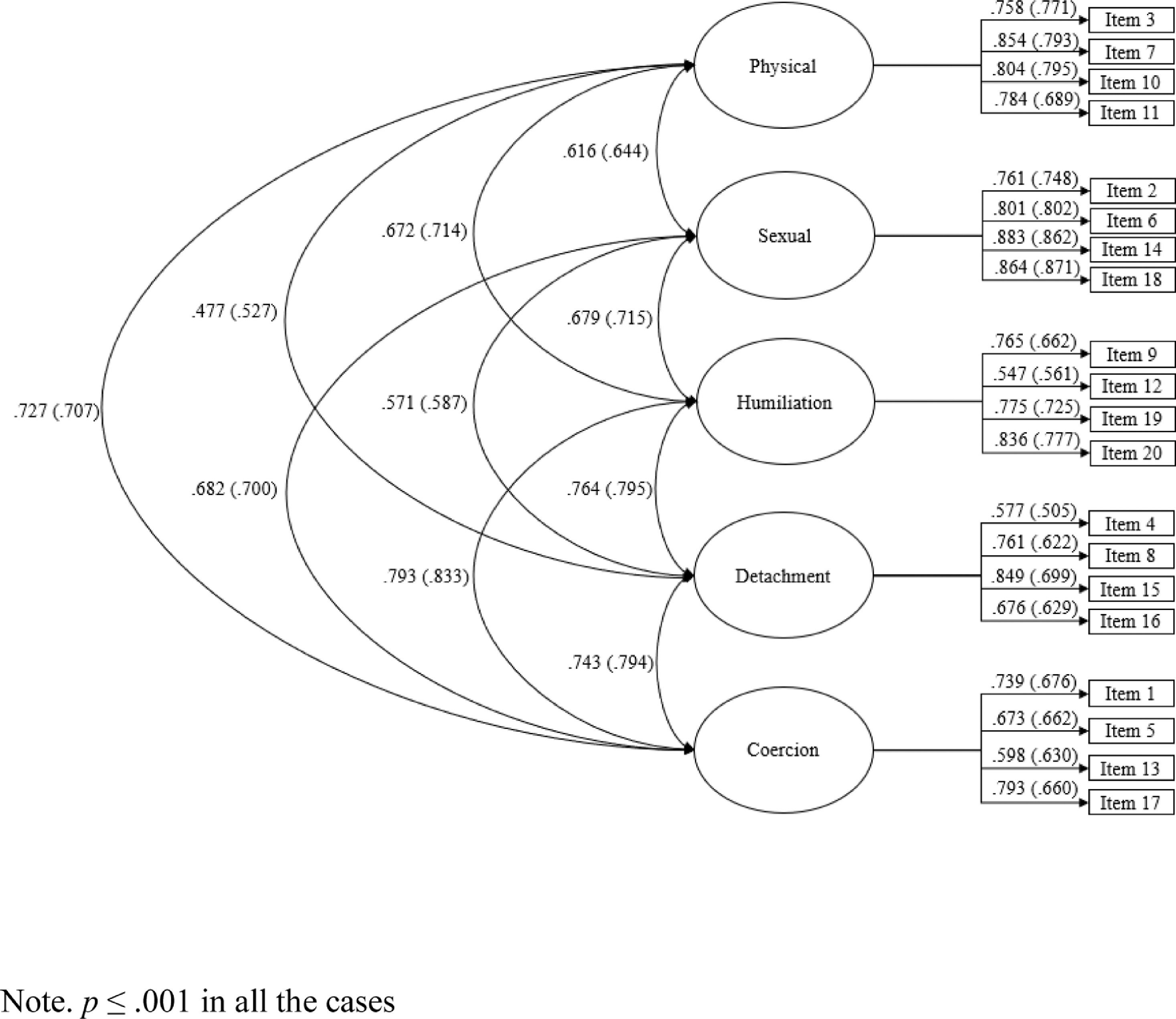

Measurement model for DVQ–RVThe dating violence victimization model was calculated based on the original five correlated factor structure. In this model, all the items significantly loaded to their corresponding factors. The model fit was good: χ2(160) = 345.24, p ≤ .001, CFI = .973, RMSEA = .031 and 90% CI [.026, .035].

Measurement model for DVQ–RPThe dating violence perpetration model was calculated based on the five correlated factor structure of the dating violence victimization model. In this model, all the items significantly loaded to their corresponding factors. The model fit was good: χ2(160) = 312.38, p ≤ .001, CFI = .967, RMSEA = .028 and 90% CI [.023, .032].

Standardized estimates for the measurement model of the DVQ–RV (out of brackets) and DVQ–RP (in brackets) are displayed in Figure 1.

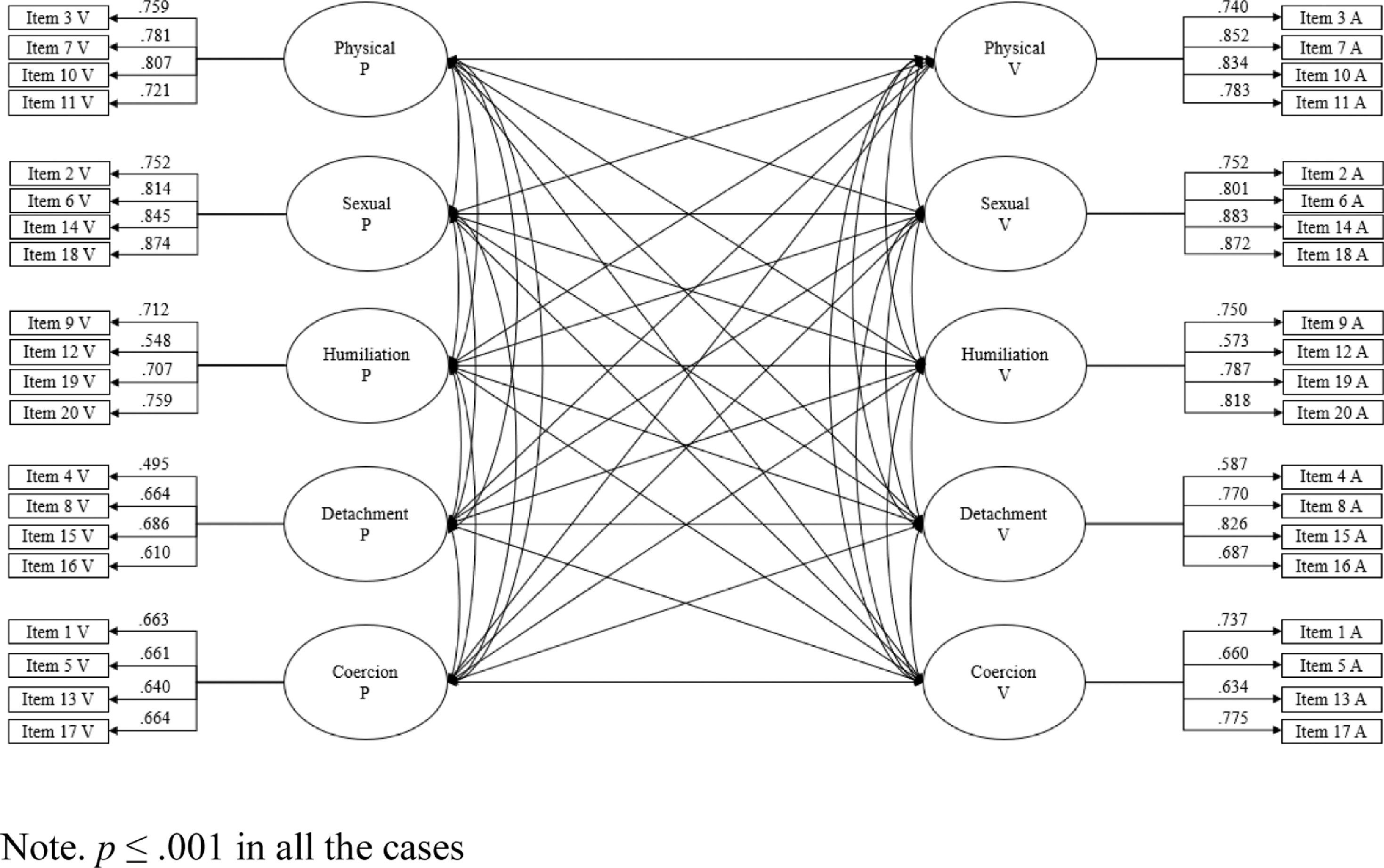

Measurement model for DVQ–VPThe dating victimization–perpetration model was calculated considering the previous two models. This model, as shown in Figure 2, is composed of ten correlated factors: five factors for victimization and five factors for perpetration. Thus, this model includes the correlations among dimensions of victimization such as the DVQ–RV (intramodel correlations), the correlations among the dimensions of perpetration such as DVQ–RP (intramodel correlations), and the correlations between the five dimensions of victimization and the five dimensions of perpetration (intermodel correlations) (see Table 1). In addition, the error terms of equivalent items (i.e., item 1 of victimization [V1] and item 1 of perpetration [P1]) were freely estimated. The model fit to the data was good: χ2(675) = 1018.83, p ≤ .001, CFI = .980, RMSEA = .020 and 90% CI [.018, .023].

Intramodel and intermodel correlations of the measurement model for DVQ-VP.

Note. p ≤ .001 in all the cases

The correlations between the ten factors (five factors of victimization and five factors of perpetration) are displayed in Table 1. The intramodel correlations varied between .477 and .793 for victimization and between .527 and .793 for perpetration. The intermodel correlations varied from .410 to .750. All the correlations were statistically significant (p ≤ .001).

Invariance across sexes for the DVQ-VP modelOnce the model fit to the data was tested and its goodness was confirmed, the invariance of the model across sexes (male and female) was tested at the configural, metric, and scalar levels; and the fit indices and model comparisons are presented in Table 2. The results displayed in Table 2 show that the model is invariant across sexes. The configural model showed a good fit (χ2(1350) = 1673.73, p ≤ .001, CFI = .980, RMSEA = .020 and 90% CI [.016, .023]), confirming that the organization of the tested constructs is supported in both groups. The metric model also showed a good fit (χ2(1380) = 1704.76, p ≤ .001, CFI = .980, RMSEA = .020 and 90% CI [.016, .023]); thus, the factor loadings are equivalent across groups. Finally, the scalar model also showed a good fit (χ2(1410) = 1722.88, p ≤ .001, CFI = .981, RMSEA = .019 and 90% CI [.016, .022]), so any differences found between groups in the latent construct captured all mean differences.

Finally, Table 3 displays the reliabilities of the ten factors (five factors of perpetration and five factors of victimization). All the reliabilities varied between .78 and .92, showing good reliability. A breakdown of the descriptive information of the ten different factors is displayed in Table 3. The results show that psychological forms of DV (detachment, coercion, and humiliation), followed by physical and sexual violence, respectively, were the most common forms of perpetration and victimization.

DiscussionThe current research tested the measurement models of DVQ–RV/DVQ–RP independently and tested the measurement model based on the interdependence approach for the Dating Violence Questionnaire for Victimization and Perpetration (DVQ–VP), which includes both dyad members’ self-reports of IPV victimization and perpetration. For this purpose, the complete data of 616 heterosexual couples of young adults were used.

The original version (DVQ-R) included a five-point Likert response scale ranging from 0 for never to 4 for all of the time. The results obtained in the current research showed that some of these categories (3 for habitually and 4 for all of the time) were systematically misrepresented. The lack of representation of the higher categories of responses when measuring violence is not a new issue, and it is related to the nature of the community sample. The probability of choosing higher categories that represent higher frequencies and are interpreted as more severe violence is lower in community samples than in other samples that tend to show more severe and frequent forms of violence (e.g., penitentiary samples) (Cunha & Gonçalves, 2017). In this regard, collapsing some category responses was considered appropriate since it (a) did not imply a significant loss of information because it was misrepresented and (b) increased the simplicity and interpretability. At this point, it is important to note that collapsing categories 3 and 4 into category 2 is coherent with the nature of the scale because those respondents who answer 3 and 4 would respond 2 in the case of using only a trichotomic response scale as the options refer to the increasing frequency of a behavior. This type of modification can be observed in other research where fewer category responses were used compared to the original version (e.g., the CTS; see Johnson et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2020; Muñoz-Rivas et al., 2007; Schnurr et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2015). Thus, this modification reduces the range of the frequency but still allows researchers to differentiate categories according to the nature of DV (CDC, 2020). The obtained results add to previous research and suggest that using fewer category responses for items is a more suitable option for future research.

The obtained results show that the DVQ is a reliable and valid measurement instrument for the independent assessment of DV victimization and perpetration and an interdependent measure of victimization and perpetration. Congruent with previous research (Alfaro-Urquiola, 2020; Cherrez-Santos et al., in press; Lara & López-Cepero, 2018; López-Cepero et al., 2016; Presaghi et al., 2015; Rodríguez-Díaz et al., 2017; Rodríguez-Franco et al., 2010), the validity of the DVQ model for victimization was demonstrated. Furthermore, in the current research, the free estimation of certain parameters included in the original version (see Rodríguez-Díaz et al., 2017) was not required, in line with more recent research (Cherrez-Santos et al., in press). The difference in these results is attributable to the different estimators used in each research. For example, Rodríguez-Díaz et al. (2017) used the maximum likelihood estimation; and Cherrez-Santos et al. (in press) used the Mean and Variance adjusted Weighted Least Square (WLSMV) estimator, as in the current study, which is considered the more appropriate estimator for modeling categorical or ordered data (see Brown, 2006). In a similar fashion, the perpetration version of the DVQ-R consisting of analogous items referring to perpetration instead of victimization also showed good validity. As this measurement instrument has never been used in this way, there is no previous empirical evidence on independent samples to which we can compare our results. Nonetheless, the results obtained in the current research are congruent with previous victimization model results, as usually occurs with other measurement instruments with analogous items for perpetration and victimization (e.g., CTS-2 or CADRI).

Although different measurement instruments allow researchers to evaluate self-reported perpetration and victimization with analogous items, the validity has been traditionally tested considering them as two independent scales and, thus, without considering the potential interdependence between self-reports of victimization and self-reports of perpetration. As shown in recent research, own victimization self-reports are predicted by own perpetration self-reports, so a significant part of victimization reported by participants is explained by their own perpetration (Herrero et al., 2020; Juarros-Basterretxea et al., in press).

Following these recent results, the main aim of the current research was to test the measurement model based on the interdependency approach for the Dating Violence Questionnaire for Victimization and Perpetration (DVQ-VP). From this perspective, which considered the interdependence between participants’ reports of victimization and perpetration, a victimization-perpetration measurement model was tested and showed a good fit to the data. As for the perpetration measurement model, there is no previous empirical research that permits a comparison, but the fit of the interdependent model is congruent with previous results obtained for independent models of victimization and perpetration.

Additionally, the DVQ–VP is invariant across sexes; thus, the perpetration–victimization model is equal for males and females, improving the generalizability of the model. The configural, metric and scalar invariance allow researchers to precisely interpret latent mean differences (Putnick & Bornstein, 2016; Vanderberg & Lance, 2000), demonstrating that the models have the same form, that the items contribute similarly to the latent construct for males and females, and that differences in the latent construct capture all mean differences.

These results show the relevance of considering perpetration and victimization together to obtain more precise knowledge of the DV phenomena and thus the necessity to develop valid measurement instruments that consider this interdependence to address the diversity of scenarios that can explain it: (1) the existence of mutual violence (victim-offender overlap) and being engaged in a violent couple dynamic in which both couple members are victims and perpetrators; (2) the perpetration of reactive violence as retaliation or self-defense, explaining violence perpetration as a consequence of the previous victimization; and (3) the upwards victimization bias or the tendency to find justification for one's own perpetration biasing the levels of victimization and increasing them. From this theoretical approach, the proposed model has important practical implications in measuring and understanding DV and emphasizes the necessity to be cautious regarding the excessive reliability of individual self-reports of only perpetration or victimization.

The current research possesses strengths and potential limitations. This study extends the knowledge on a valid and reliable assessment instrument by supporting the results obtained in previous research (Rodríguez-Díaz et al., 2017) and is, to our knowledge, the first study reporting evidence on the reliability (internal consistency) and validity (factor structure and invariance) of a DV/IPV measurement instrument considering the interdependence between one's own perpetration and victimization reports. The inclusion of the interdependent nature of DV victimization and perpetration (Herrero et al., 2020; Juarros-Basterretxea et al., in press) is an innovative approach and contributes to advancing the field by presenting a useful and brief DV perpetration–victimization model formed using empirical evidence misrepresented in much research (Exner-Cortens et al., 2016b). Nonetheless, the DVQ-VP possesses the inherent limitations of behavioral measurement instruments (Hardesty & Ogolski, 2020), and it would be beneficial for future research to use it together with other instruments and data collection methods and to test its convergent and divergent validity considering different levels of correlates of IPV (Dardis et al., 2015; Hammock et al., 2017; Herrero et al., 2016, 2018; Juarros-Basterretxea et al., 2018, 2019, 2020). Likewise, it would be convenient to include other information sources and methods to assess real injury (Vilariño et al., 2018) and to verify the victimization and perpetration (Gancedo et al., 2021).

Furthermore, the sample of the current research also represents an important strength. First, all the participants must be engaged in an intimate relationship at the time of the study, which makes the data more reliable than those of other studies based on previous or last relationships because of the lower memory recall bias (Exner-Cortens et al., 2016b). Second, the study's sample size exceeds the sample sizes of other studies (Exner-Cortens et al., 2016a), especially considering that the sample was composed of current couples. Nevertheless, it is also true that the sample was not representative, so any generalization of the data must be done cautiously. For instance, generalized and specific perpetrators have not been included (Cantos et al., 2019). Similarly, even though the number of participating couples was high, they were all heterosexual couples, and future research should replicate these results considering more diversity among couples (Edwards et al., 2015; Harden et al., 2020; Laskey et al., 2019; Lin et al., 2020; Martínez-Gómez et al., 2021; Peitzmeier et al., 2020; Ramiro-Sánchez et al., 2018; Rojas-Solís et al., 2019).

In conclusion, the DVQ–VP is the only DV measurement instrument considering the interdependence of perpetration and victimization self-reports that has been validated, allowing its use regardless of the sex of the participants. The inclusion of the interdependence of self-reported scores is a methodological improvement in the DV measure that better measures and understands DV and the complex link between victimization and perpetration. In line with its predecessor, the DVQ–R, the DVQ-VP is a valid, reliable, and relatively short measurement instrument potentially applicable to young samples in the community to conduct the primary detection of DV perpetration and victimization.

FundingSupport for this research was provided by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (Reference PID2020-114736GB-I00).