WazzUp Mama© is a remotely delivered web-based tailored intervention to prevent and reduce perinatal emotional distress, originally developed in the Netherlands. The current study aimed to evaluate the adapted WazzUp Mama© intervention in a Flemish (Dutch-speaking part of Belgium) perinatal population.

MethodsA 1:3 nested case-control study was performed. A data set including 676 participants (169 cases/507 controls) was composed based on core characteristics. Using independent t-test and chi-square, the two groups were compared for mean depression, self and perceived stigma, depression literacy scores, and for positive Whooley items and heightened depression scores. The primary analysis was adjusted for covariates.

ResultsThe number of positive Whooley items, the above cut-off depression scores, mean depression, perceived stigma, and depression literacy scores showed statistically significant differences between cases and controls, in favor of the intervention group. When adjusting for the covariates, the statistically significant differences between cases and controls remained for depression, perceived stigma, and depression literacy, for the positive Whooley items and for above cut-off depression scores.

ConclusionWazzUp Mama© indicates to have a moderate to large positive effect on optimizing perinatal emotional wellbeing, to positively change perceived stigma and to increase depression literacy.

Perinatal emotional distress is reported by six to 61 % of childbearing women worldwide, with varying prevalence rates per country (Wang et al., 2021). Perinatal emotional distress refers to a spectrum of psychological symptoms during the antenatal and postpartum period, varying in severity from reduced sense of welfare, health and happiness, feelings of insecurity, stress, anxiety, fear, and worries, to depressive and anxiety disorders and disturbed psychological functioning (Emmanuel & St John, 2010; Ridner, 2004). Depression, stress, and anxiety, either pregnancy or non-pregnancy/birth related, are the most mentioned constructs of perinatal emotional distress (Fontein-Kuipers et al., 2014). Perinatal emotional distress is adversely associated with impaired maternal and infant health, family functioning and child development (Howard & Khalifeh, 2020; Rogers et al., 2020).

Perceived public stigma (others holding negative attitudes towards those with emotional health problems), self-stigma (internalized shame and self-blame), and limited knowledge of, or negative or incorrect beliefs about perinatal emotional distress affect perinatal women in seeking professional help (Jones, 2019; Jones, 2022; Thorsteinsson et al., 2018). Women with perinatal emotional problems are less inclined to share their burden with their care provider (Forder et al., 2020). Instead, they are more likely to disclose online (Amoah, 2021; Evans et al., 2022; Fontein-Kuipers & Jomeen, 2018). Online supportive measures tailored to individual, country, and socio-cultural context, contribute to positive changes of perinatal emotional health and wellbeing of the pregnant and postpartum population (Evans et al., 2022). Freely available and easily accessible evidence-based interventions that take cultural variety and vulnerable individual characteristics into account are needed to provide quality of perinatal emotional healthcare (Manso-Córdoba et al., 2020). Additionally, low-intensity psychological self-help tools are known to support perinatal emotional health and wellbeing (Bower et al., 2013; National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health UK, 2014).

WazzUp Mama© is a remotely delivered web-based tailored intervention, aiming to prevent and reduce perinatal emotional distress. The intervention has a low-intensity character, which implies it is not provided by a specialized professional but through self-help materials (Jimenez-Barragan et al., 2023). To identify emotional distress, the stress-thermometer, the Whooley-items, and the Edinburgh Depression Scale are added to the intervention for users to self-asses the occurrence and severity of stress, depression, low mood and loss of interest or pleasure (Fontein-Kuipers et al., 2015). The intervention was initially developed for a Dutch pregnant population - its intervention mapping framework approach has been described in detail elsewhere (Fontein-Kuipers et al., 2015). A needs assessment among a Dutch pregnant population directed the development of the intervention, showing that to self-manage emotional wellbeing, health promotion and selective and indicative prevention intervention strategies were required (Fontein-Kuipers et al., 2014; Fontein-Kuipers et al., 2015). In addition, information, and advice about, and reflection on how to self-manage emotional distress in daily life by using specific adaptive coping styles and practical activities was needed (Fontein-Kuipers et al., 2015; Fontein-Kuipers et al., 2017). A specific program-built algorithmic recommendation system generated personalized feedback on, for example, which personal details are associated with being at risk for emotional distress, information about recognizing signs and symptoms of reduced emotional health and wellbeing (symptom checker), advice and tips & tricks for day-to-day life (e.g. practical support, adaptive coping strategies practical support such as self-disclosure and help-seeking), and relaxation techniques (e.g. meditation, nature sounds). The feedback was based on digitally provided responses of the individual user (Fontein-Kuipers et al., 2015). The intervention was tested for its effect in a non-randomized pre-post intervention study, showing a moderate positive effect on emotional distress when comparing the intervention and control group. The intervention group showed a significant reduction in the trait anxiety and pregnancy-related anxiety scores from first to third trimester of pregnancy, and a reduction of depression scores albeit not significant (Fontein-Kuipers et al., 2016). Although the intervention proved to be effective for a Dutch antenatal population, at this point it was not implemented on a wider level.

Flanders is the northern Dutch-speaking part of Belgium bordering the southern parts of the Netherlands. Although the Flemish and Dutch population speak the same language, it cannot be assumed that the Flemish perinatal population has the same emotional health support needs as Dutch childbearing people. Therefore, WazzUp Mama© required adaptation to the contextual socially and culturally emotional health needs of the Flemish perinatal population (Manso-Córdoba et al., 2020). Moreover, expanding the intervention to postpartum use was thought to be of merit (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health UK, 2014). A project group of perinatal care professionals and pregnant and postpartum women with and without (a history) of emotional (perinatal) health problems was regularly consulted throughout the development and implementation of the intervention to understand the practical meaning of the findings (Bartholomew Eldrigde et al., 2016). The project group stressed the importance to pay attention to the normative culture of Flemish women to contest and comply with dominant discourses about childbirth and parenting, and the shame and guilt associated with not meeting personal standards to be a perfect mother (to-be) (Geinger et al., 2013; Hubert & Aujoulat, 2018). A similar needs assessment as in the Netherlands was performed, showing additional perinatal emotional health risk factors and causes for selective prevention as well as different coping strategies among a Flemish perinatal population and a demand for improving mental health literacy (Brosens et al., 2023; Kuipers et al., 2019; van Gils et al., 2022; Van den Branden et al., 2023). The findings from the needs assessment were added to the original WazzUp Mama© intervention's content, while its algorithmic recommendation system remained unchanged. After implementation, the Flemish WazzUp Mama© was shared via a network of practitioners, social media platforms and via a multimedia campaign (August 2021-December 2022). Women could freely and anonymously access the web-based intervention using an electronic device.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the effect of the intervention WazzUp Mama© in a Flemish perinatal population by examining the differences in emotional wellbeing, stigma, and depression literacy between those who received the intervention and those who did not (care-as-usual). We hypothesized that perinatal emotional distress, personal and perceived stigma would decrease, and depression literacy increase after having used the intervention when compared with the control group.

MethodsDesign and procedureA nested case-control study was performed, including two groups. One group used WazzUp Mama© (intervention group) and one group received care-as-usual (control group). Participants where eligible when 18 years of age or older and with a good comprehension of the Dutch language. Pregnant women were included during any trimester of pregnancy and postpartum women up to one year after the birth of a healthy child when have given birth between 37 to 41 weeks’ gestation. Participants with children with severe illness and/or life-threatening conditions were excluded. Convenience and purposive sampling were combined. Health care professionals involved in perinatal care (i.e. midwives, obstetricians, doulas, physiotherapists) were asked to distribute flyers and posters among potential participants for both control and intervention group. Participants were also recruited via various social media platforms. A URL or QR-code anonymously directed participants to the questionnaire. More than 6000 women accessed the intervention after its launch. Due to General Data Protection Regulation, no IP addresses were recorded and therefore it was unknown how many unique individuals engaged with WazzUp Mama©.

Data collectionRecruitment of the participants and data collection for the control and intervention group were carried out in two sequential time periods: January 2020-July 2021 for the control group (before intervention adaptation and launch), and January-December 2022 for the intervention group. Data were collected using an online self-report questionnaire (Lime Survey©).

Sample sizeOpenEpi was used to calculate the sample size (https://www.openepi.com/SampleSize/SSCC.htm). The Dutch WazzUp Mama© pre-post intervention study indicated that the probability of incidence of cases with depression is 19.5 % among cases and 6.4 % among controls (Fontein-Kuipers et al., 2016). With a power of 80 %, α.5 and a 1:3 enrolment ratio (odds ratio .28), a minimum of 83 cases and 247 matched controls were needed.

MeasuresThe following maternal characteristics and personal details were collected: maternal age, background (Belgian/non-Belgian), highest level of education (low/medium/high), relation (in relationship/single), religion or belief, parity (nulli/primiparous or multiparous), perinatal period (pregnant or postpartum) length gestational period (in weeks, categorized in first, second or third trimester of pregnancy), postpartum period (in weeks), personal and family history of psychological problems, emotional problems in current or previous pregnancy and/or postpartum period, and type of birth. The primary outcomes of interest were potential low mood and loss of interest or pleasure, depression, personal and perceived stigma, and depression literacy.

Whooley questionsThe two Whooley case-finding items identify potential low mood and loss of interest or pleasure among women during the perinatal period. Questions were answered positively (yes) or negatively (no) (Whooley et al., 1997). A positive response to at least one Whooley item was considered as a positive test (Mann et al., 2012). In a Dutch-speaking population the items showed to accurately identify depression and anxiety in first and third trimester of pregnancy (sensitivity 69–74 %; specificity 85–88 %) (Fontein-Kuipers & Jomeen, 2018). In a postnatal population the items showed 100 % sensitivity and 65 % specificity (Mann et al., 2012).

Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS)The EPDS is a ten-item questionnaire to screen for the likelihood of depression among pregnant and postpartum women (Murray & Cox, 1990). Participants were asked to reflect on their feelings and thoughts of the last seven days. Responses were scored 0-3 in seriousness of symptoms, with a total score range from 0 to 30. In this study, validated cut-off scores ≥11 for women in the first trimester, ≥10 for women in the second or third trimester of pregnancy and ≥13 for postpartum women were used (Bergink et al, 2011). Cut-off scores yielded sensitivity (70–79 %) and specificity (94–97 %) in each trimester of pregnancy (Bergink et al., 2011).

Depression stigma scale (DSS)The DSS comprises 18 items representing two subscales: personal stigma (self-stigma) and perceived stigma (perceptions of stigma of others) (Griffiths et al., 2004; Barney et al., 2010). The items were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from strongly disagree (0) to strongly agree (4) with a total score in the range of 0–36 for each of the two nine-item sub-scales, a higher score indicating greater stigma (Barney et al., 2010; Boerema et al., 2016). The scale showed internal consistency in a Dutch-speaking population (α .71-.78; α 73-.82) (Boerema et al., 2016).

Depression literacy scale (DLQ)The DLQ consists of 22 items to evaluate knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of depression in individuals. The questions could be scored with ‘false’, ‘true’ or ‘I don't know’. The correct answers were summed as a total score, a higher score indicating a better ability to recognize and understand depression (Griffiths et al., 2004; Ram et al., 2016). The scale showed Cronbach's alpha coefficient varying from .70–.78, and test-retest reliability ranging from .7-.91 (Griffiths et al., 2004; Ram et al., 2016).

AnalysisWe compared the characteristics of completers with non-completers (women who partially filled in the questionnaires) and of the cases and the controls, using T-test and chi-square. When more than 10% values were missing per case, control, or variable, these were excluded for further analysis. To measure between-group differences in the primary outcomes, each case was matched with three controls to reduce confounding and to enhance comparability of characteristics in the study population, with relatively minor loss in statistical efficiency (Ernster, 1994; Nielsen, 2016; Rose & van der Laan, 2009). We created identical pairs of cases and controls (1:3) based on core characteristics known to be associated with perinatal emotional distress (Bloom et al., 2007). Exact matching was performed randomly using statistical software. The between-group differences were measured with an independent t-test analysis and chi-square. Pearson and Point-Biserial Correlation were used to estimate the correlation between fidelity and the primary outcomes. Covariates were chosen based on differences between completers and non-completers and between cases and controls. The analysis adjusting for covariates was performed with MANCOVA for continuous variables, and binary logistic regression for dichotomous categorial variables. Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen's d and relative risk (RR). Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 27.0 was used for analysis.

EthicsThe study received approval from the Research and Ethics Committee of the Antwerp University Hospital (SHW_19_34). Participants digitally consented to participate before they could complete the questionnaire.

ResultsA total of 1502 questionnaires were received from the controls and 222 from the cases. From the responders (1453/96.7 %) in the control group, 990 (61.4 %) completed questionnaires were eligible. From the responders in the intervention group (183/82.4 %), 169 (95.5 %) completed questionnaires could be included for analysis (Fig. 1). The completers in the intervention group reported significantly more often a history of emotional problems during current or previous pregnancy and/or postpartum, compared with the non-completers (p < 001).

ParticipantsAll participants self-identified as female. Participants in both the intervention and control group most often had a Belgian background, reported high levels of education and were predominantly in a relationship. Over a third of the participants in both intervention and control group reported a history of psychological problems. Both groups contained slightly more nulli/primiparous than multiparous women. There were significant differences between the characteristics of the cases and controls, being: level of education (p < 001), religion or belief (p < 001), perinatal period (p < 001), and gestational age (p < 001) (Table 1). The cases had accessed WazzUp Mama© between one to 12 times before completing the questionnaire.

Demographic and personal details control and intervention group.

| CONTROL GROUP N = 990 | INTERVENTION GROUP N = 169 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD; range) | N / % | Mean (SD; range) | N / % | P | |

| Age | 30.20 (SD 3.72; 18-47) | 30.57 (SD 3.60; 22-46) | 0.24 | ||

| Background (nationality)BelgianNon-Belgian | 924 / 93.366 / 6.7 | 158 / 93.511 / 6.5 | 0.94 | ||

| Highest level of education*LowMediumHigh | 38 / 3.9139 / 14813 / 82.1 | - / -1 / 0.6168 / 99.4 | <0.001 | ||

| RelationIn a relationshipsingle | 950 / 9640 / 4 | 166 / 98.23 / 1.8 | 0.15 | ||

| Religion or beliefYesNo | 231 / 23.4756/76.6 | 24 / 14.2145/ 85.8 | <0.001 | ||

| Personal history of mental/psychological problemsYesNoTreatment received (n = 327)YesNo | 327 / 33663 / 67246 / 75.281 / 24.8 | 63 / 37.3106 / 62.748 / 69.615 / 30.4 | 0.280.87 | ||

| Family history of mental/psychological problemsYesNoUnknow | 331 / 33.4568 / 57.491 / 9.2 | 45 / 26.6120 / 71.04 / 2.4 | 0.80 | ||

| (History of) perinatal emotional problemsYesNo | 212 / 21.4778 / 78.6 | 37 / 21.9132 / 78.1 | 0.89 | ||

| Perinatal periodPregnantPostpartum | 564 / 56.9426 / 43.1 | 77 / 45.692 / 54.4 | <0.001 | ||

| Nulli/primiparousMultiparous | 541 / 54.6449 / 45.4 | 85 / 50.384 / 49.7 | 0.29 | ||

| Gravidity (including current/last pregnancy) | 1.84 (SD 1.16; 1-12) | 1.87 (SD 1.10; 1-6) | 0.76 | ||

| Parity | 0.97 (SD 0.82; 0-5) | 1.10 (SD 0.89; 0-3) | 0.06 | ||

| Gestational age in weeks | 24.10 (SD 9.87; 2-41) | 30.13 (SD 10.14; 1-40) | <0.001 | ||

| Weeks postpartum | 20.61 (SD 15.0; 1-53) | 19.90 (SD 16.31; 2-53) | 0.58 | ||

| Method of birthSpontaneous vaginal birthInstrumental birthPrimary caesarean sectionSecondary caesarean section | 279 / 65.553 / 12.435 / 8.259 / 13.9 | 58 / 63.09 / 9.811 / 12.014 / 15.2 | 0.66 | ||

| Number of times WazzUp Mama© used | - | 3.17 (SD 2.43; 1-12) | |||

A data set including 676 questionnaires (1:3 matching) was constructed. We created identical pairs of cases and controls (1:3) on the variables: maternal age, background (Belgian/non-Belgian), perinatal period (pregnancy/postpartum), trimester of pregnancy when pregnant (1st, 2nd, 3rd), parity (0, 1 or more), and personal history of emotional problems (yes/no), perinatal period, parity, trimester of pregnancy, background, and age in years. The final data set included 169 cases (intervention group) and 507 controls (control group). The matched case-control cohort showed no differences in baseline characteristics, confirmed by the Mahalanobis distances, which showed no outliers. The matching variables showed weak correlations (r.1 to r.3).

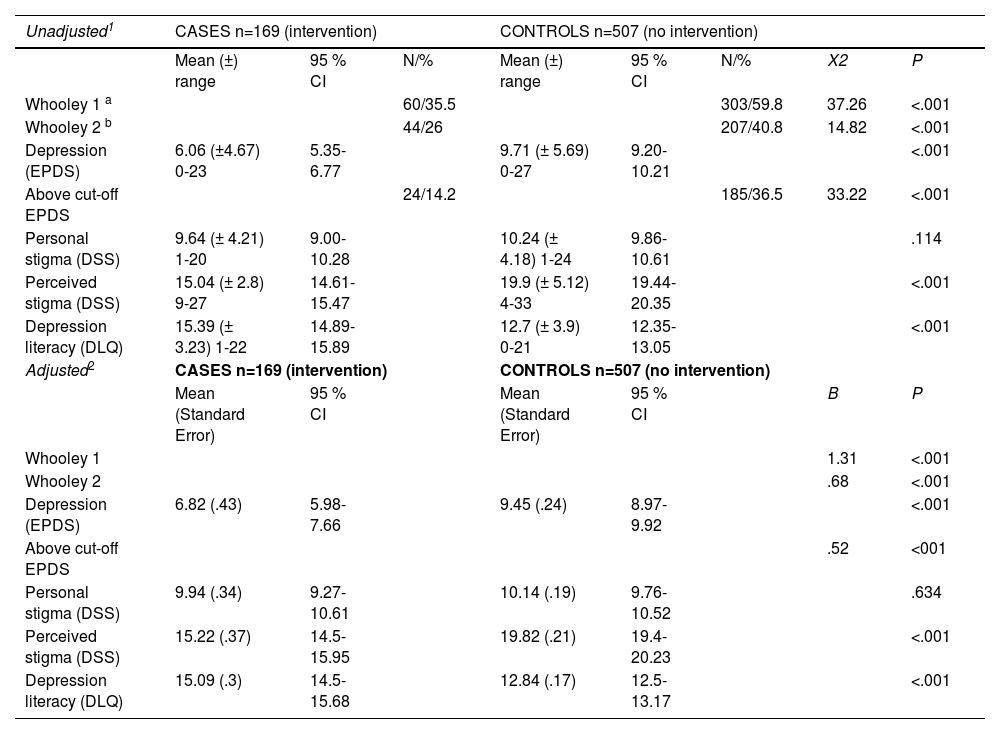

The mean depression scores in the intervention group were significantly lower compared with the control group (p < 001, d-.67). Perceived stigma scores in the intervention group were significantly lower than in the control group (p < 001, d-1.0) and depression literacy scores in the intervention group were significantly higher compared with the control group (p < 001, d.72), showing a moderate to large effect. The Whooley two-items showed RR .59 and .64, and the above cut-off EPDS scores RR .39, all demonstrating a statistically significant difference between cases and controls in favor of the intervention group (p < 001; p < 001; p < 001). When adjusting for the covariates (relation, religion or belief, level of education, (history of) perinatal emotional problems), the statistically significant difference between cases and controls remained for the EPDS, DSS perceived stigma and the DLQ total scores (p < 001; p < 001; p < 001), for positive Whooley two-items and for above cut-off EPDS scores (p < 001; p < 001; p < 001) (Table 2).

Between group differences primary outcomes

| Unadjusted1 | CASES n=169 (intervention) | CONTROLS n=507 (no intervention) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (±) range | 95 % CI | N/% | Mean (±) range | 95 % CI | N/% | X2 | P | |

| Whooley 1 a | 60/35.5 | 303/59.8 | 37.26 | <.001 | ||||

| Whooley 2 b | 44/26 | 207/40.8 | 14.82 | <.001 | ||||

| Depression (EPDS) | 6.06 (±4.67) 0-23 | 5.35-6.77 | 9.71 (± 5.69) 0-27 | 9.20-10.21 | <.001 | |||

| Above cut-off EPDS | 24/14.2 | 185/36.5 | 33.22 | <.001 | ||||

| Personal stigma (DSS) | 9.64 (± 4.21) 1-20 | 9.00-10.28 | 10.24 (± 4.18) 1-24 | 9.86-10.61 | .114 | |||

| Perceived stigma (DSS) | 15.04 (± 2.8) 9-27 | 14.61-15.47 | 19.9 (± 5.12) 4-33 | 19.44-20.35 | <.001 | |||

| Depression literacy (DLQ) | 15.39 (± 3.23) 1-22 | 14.89-15.89 | 12.7 (± 3.9) 0-21 | 12.35-13.05 | <.001 | |||

| Adjusted2 | CASES n=169 (intervention) | CONTROLS n=507 (no intervention) | ||||||

| Mean (Standard Error) | 95 % CI | Mean (Standard Error) | 95 % CI | B | P | |||

| Whooley 1 | 1.31 | <.001 | ||||||

| Whooley 2 | .68 | <.001 | ||||||

| Depression (EPDS) | 6.82 (.43) | 5.98-7.66 | 9.45 (.24) | 8.97-9.92 | <.001 | |||

| Above cut-off EPDS | .52 | <001 | ||||||

| Personal stigma (DSS) | 9.94 (.34) | 9.27-10.61 | 10.14 (.19) | 9.76-10.52 | .634 | |||

| Perceived stigma (DSS) | 15.22 (.37) | 14.5-15.95 | 19.82 (.21) | 19.4-20.23 | <.001 | |||

| Depression literacy (DLQ) | 15.09 (.3) | 14.5-15.68 | 12.84 (.17) | 12.5-13.17 | <.001 | |||

A negative significant correlation was observed between frequency of use of the intervention and personal stigma (r -.26, p .01) but no significant correlations were established for the other outcomes Whooley one (r -.16, p.15), Whooley two (r -.13, p.21), EPDS (r .18, p.1), above cut-off EPDS (r .12, p.28), perceived stigma (r -.03, p.8), and depression literacy (r -.12, p.26).

DiscussionWazzUp Mama© is a low-intensity remotely delivered web-based tailored intervention, in content an adapted version of the Dutch WazzUp Mama© tool. The original tool used the intervention mapping as the theoretical and systematic framework for its content and structural development and production of the intervention (Fontein-Kuipers et al., 2015). The positive effect of the Dutch intervention was explained by this systematic approach (Fontein-Kuipers et al., 2016). As the Flemish WazzUp Mama© tool adopted the structure of the Dutch version, it is likely that this also might have contributed to the positive effect of the Flemish adapted tool (Bartholomew Eldrigde et al., 2016). Like the Dutch version, the Flemish intervention is based on cultural contextual needs and tailored to the woman's individual situation, which might additionally explain the positive effect of the intervention (Fontein-Kuipers et al., 2016; Manso-Córdoba et al., 2020). The repeated positive effect of WazzUp Mama© indicates the potential to adapt the tool for perinatal populations in other countries and cultures than Belgium and the Netherlands.

Although personal stigma was lower in the intervention group than in the control group, this did not decrease significantly as we hypothesized. Personal stigma is known to be associated with self-blame (Aromaa et al., 2011). Self-blame has shown to be a significant maladaptive coping strategy of Flemish perinatal women (Brosens et al., 2023; van Gils et al., 2022). Although depression literacy is known to reduce personal stigma (Thorsteinsson et al., 2018), a negative significant correlation was found between frequency of use of the intervention and personal stigma, suggesting that targeting personal stigma might require a different intervention or approach (Yanos et al., 2015). It is likely that individual women engage, respond, or benefit differently to the intervention and therefore it can be recommended to further explore the use of the intervention in relation with coping strategies of women who engaged with WazzUp Mama© - in terms of if and how the intervention affected their coping behaviour - self-blame being a coping strategy of interest (Brosens et al., 2023).

The intervention was accessed more than 6000 times, and women engaged approximately three times with the tool during the perinatal period, suggesting that women possibly only accessed the intervention when seeking particular information (Evans et al., 2022) or that tailoring is more effective than fidelity (Yanos et al., 2015). There was no significant positive correlation between frequency of use of the internet-based tool and emotional wellbeing although evidence suggest this to occur in populations with more severe emotional distress (Bower et al., 2013). We had no baseline measures of the intervention group to examine the within-group treatment effect, thus being unaware of the cases’ emotional wellbeing before using the intervention. Building on the evidence of the Dutch pre-post intervention study that showed comparable levels of baseline emotional wellbeing in both the control and intervention group (Fontein-Kuipers et al., 2016), it can be assumed that, based on the understanding of high levels of existing emotional distress (Bower et al., 2013), baseline emotional wellbeing among the Flemish cases was positively affected by the intervention. More specifically, the Whooley and EPDS outcome scores in the control group suggests the intervention is effective for the reduction of depression and to lift low mood and negative thoughts and to increase interest or pleasure in doing things.

The data were collected in subsequent periods of which the first period of data collection (control group) took place during the COVID-19 pandemic. This could have explained the higher response rate, and the higher incidence and mean scores of emotional distress (Tomfohr-Madsen et al., 2021). When the intervention was introduced and evaluated, the pandemic lockdown restrictions had eased, which might have moderated the positive effect on perceived stigma, and depression literacy as during the aftermath of the pandemic the impact on wellbeing of families received a lot of attention (Briana et al., 2022). Because case recognition ties in with a better ability to recognize and understand depression (Wang & Lai, 2008), the COVID-19 pandemic might have confounded our results.

Strengths and limitationsThe main challenge in this comparison of results from the intervention and control group is the comparability of participants in both groups (Nielsen, 2016). We were able to select controls and cases from the same population thus avoiding selection bias (Niven et al., 2013; Rose & van der Laan, 2009). Using matching, we were able to create a comparable sample of controls with respect to maternal characteristics. We were aware that the matching variables were associated with emotional distress, increasing study precision (Bloom et al., 2007). Although our matching procedure successfully minimized confounding by age, background, perinatal period, and parity, other factors could still cause differences between the cases and controls. Based on the low correlations between the matching variables, we assume the matched cohort does not lead to important bias (Nielsen, 2016; Rose & van der Laan, 2009). Nevertheless, participants in the intervention group may be different from those in the control group in other important ways that were not included in our study (Partlett et al., 2020).

Our sample exceeded the calculated minimum number of participants, enhancing the validity of our findings. The choice of three controls seems justified because gains in statistical efficiency are possible by using more than four controls is low and might have led to repeated sampling, resulting in duplicates in the matched control population, specifically for background, lower and higher maternal age, nulli/primiparity and history of emotional problems (Partlett et al., 2020). We also must bear in mind that cross-over between the groups was possible, affecting the matching strategy.

The disproportion between frequency of use and the lower response rate of the intervention group might be caused by the self-selective nature of the study. Like most studies involving self-reporting of potentially subjective experiences, social desirability can be regarded as a limitation of our study. Additionally, the Hawthorne effect might have been a potential limitation when overestimating desirable behaviors. However, the nested case-control methodology provides strong evidence for the validity of the findings because the comparison between the cases and matched controls could be made at the point after exposure (Partlett et al., 2020). Additionally, online self-reporting of perinatal emotional wellbeing is known to provide reliable answers, enhancing the reliability of the findings (Amoah, 2021; Evans et al., 2022; Fontein-Kuipers & Jomeen, 2018).

When comparing our sample with the Flemish perinatal population, our sample shows a good representation of the population of interest in terms of maternal age, education, parity, mode of birth and history of emotional problems (Brosens et al., 2023; Goemaes et al., 2022; Kuipers et al., 2022; Van den Branden et al., 2023). The findings of our study are however only generalizable to women with similar characteristics. We note that the lack of availability of the intervention in other languages may have influenced the recruitment of participants. To ensure inclusivity, outreach support to extend recruitment beyond those from this majority culture needs to be considered.

ConclusionThis nested case-control study showed that WazzUp Mama© is an effective tool to support women in their perinatal emotional wellbeing. Receiving the intervention had a significant moderate to large positive effect on emotional wellbeing, perceived stigma and on depression literacy when compared to those not receiving the intervention. Those who received the intervention showed a significantly lower incidence of low mood and loss of interest or pleasure, lower levels of depression and perceived stigma and significantly higher levels of depression literacy compared with the control group. The use of intervention mapping and tailoring to women's cultural contextual needs and individual needs suggest the positive effect of the intervention. The nested case-control methodology proved to be an efficient way to investigate a causal relationship between the use of WazzUp Mama© and depression, perceived stigma, and depression literacy.

FundingThis work was supported by The Interreg 2 Seas Mers Zeeen (Grant No. 2S05-002, 2019), The Department of Economy, Science & Innovation of the Flemish Government (Grant No. 3105R2006, 2019), and The Province Antwerp Service for Europe, Department of Economy, Local Policies and Europe (Grant No. BBSPATH 1564468860780, 2019).

CRediT authorship contribution statementYvonne J Kuipers: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Supervision. Roxanne Bleijenbergh: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Sophie Rimaux: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Eveline Mestdagh: Validation, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

N/A