Mental disorders are considered to be the main reason for the increase of the disease burden. College students seem to be more vulnerable to the adverse effects of stress, which makes them more at risk of suffering from mental disorders. This umbrella review aimed to evaluate the credibility of published evidence regarding the effects of interventions on mental disorders among university students.

MethodsTo identify systematic reviews and meta-analyses investigating the effects of interventions on mental disorders in the university student population, extensive searches were carried out in databases including PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Database, spanning from inception to July 21, 2023. Subsequently, a thorough reanalysis of crucial parameters such as summary effect estimates, 95 % confidence intervals, heterogeneity I2 statistic, 95 % prediction intervals, small-study effects, and excess significance bias was performed for each meta-analysis found.

ResultsNineteen articles involving 74 meta-analyses were included. Our grading of the current evidence showed that interventions based on exercise, Cognitive-behavioural Intervention (CBI), mindfulness-based interventions (MBI), and other interventions like mood and anxiety interventions (MAI) were effective whereas exercise intervention had the highest effect size for both depression and anxiety among university students. However, the credibility of the evidence was weak for most studies. Besides, suggestive evidence was observed for the positive effects of CBI on sleep disturbance(SMD: -0.603, 95 % CI: -0.916, -0.290; P-random effects<0.01) and MAI on anxiety (Hedges'g = -0.198, 95 % CI: -0.302, -0.094; P-random effects<0.01).

ConclusionBased on our findings, it appears that exercise interventions, CBI, and MAI have the potential to alleviate symptoms related to mental disorders. Despite the overall weak credibility of the evidence and the strength of the associations, these interventions offer a promising avenue for further exploration and research in the future. More high-quality randomized controlled trials should be taken into account to verify the effects of these interventions on various mental disorders.

Mental disorders are increasingly considered the major driver of the growth of disease burden and a worldwide public health concern ("Global, regional & national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries & territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019,", 2022). The global burden of diseases study (GBD) 2019 finds that depression and anxiety are rated as the 13th and 24th leading causes of DALYs, respectively, with prevalence estimates and disability significantly higher than other diseases ("Global, regional & national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries & territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019,", 2022).

Mental illness can negatively affect many people throughout their entire lives in different forms and degrees (Vigo, Thornicroft & Atun, 2016). It is suggested that students are vulnerable populations because they are often susceptible to the impacts of stress (Auerbach et al., 2016). To be specific, post-secondary students are at a high risk of developing mental health problems and university students may suffer from mental diseases in any given year (Auerbach et al., 2018; Ibrahim, Kelly, Adams & Glazebrook, 2013). Mental disorders can lead to various longstanding negative impacts, including poor academic performance, increased dropout rates, lowered life satisfaction, and even increased suicide risk (Gong et al., 2023; Sheldon et al., 2021).

Despite the Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development advocating for paying more attention to mental health and emphasizing more investment in mental health services, global decision-makers and funders fail to realize the importance of treatment and support of people with mental diseases to some extent (Saxena, Thornicroft, Knapp & Whiteford, 2007; Sheldon et al., 2021). Given the imbalance between the increasing global burden of mental disorders and insufficient attention to mental health, evaluating and determining an effective intervention for people with mental illness is necessary.

To date, a great variety of mental health promotion interventions have been developed for people with common mental illnesses. Although methodological approaches differed between existing studies, the main promising ways include physical exercise, cognitive behavioural therapy, mindfulness-based intervention, art intervention, educational intervention, support groups, etc. totally(Sun et al., 2022). Such interventions might exert a positive effect in alleviating mental disorders. However, limited reviews systematically evaluate the effectiveness of various interventions for mental disorders, in which many of them are focused on a single topic. As such, the existing evidence is prone to occur bias like publication bias and excess significance bias, leading to an overestimated result(Jüni, Altman & Egger, 2001).

Umbrella reviews are increasingly taken into account as a methodological way to consolidate the highest quality level of evidence by merging and assessing the systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Kim et al., 2021; Papatheodorou, 2019). Compared with conventional meta-analyses examining the same treatment comparison, umbrella reviews give a more comprehensive overview of different treatments on the given question. It enables researchers to re-assess the risk of bias and hierarchies of evidence of published studies, allowing decision-makers to develop an objective guideline (Ioannidis, 2009).

Therefore, we aimed to perform an umbrella review of systematic reviews with meta-analyses to assess the effects of interventions for mental disorders in university students and evaluate the certainty of the evidence.

MethodThis umbrella review was conducted by Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021). The study was registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under the registration number CRD42023450905.

Search strategy and study selectionWe systematically searched the electronic databases PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane from inception to 21 July 2023. The full search strategy is available in the Supplemental Methods. There were no language restrictions. To identify potentially eligible studies, two reviewers (HH and HSF) independently screened titles and abstracts followed by full-text screening. We also hand-searched the references list of eligible studies to identify further relevant articles. All discrepancies were resolved by consensus through discussion with a third reviewer (ZFF). If 2 or more published meta-analyses examined an identical theme, we included the most recent meta-analysis with the largest number of individual studies and high-quality studies to avoid overlaps (Ioannidis, 2009).

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaThe identified studies were independently reviewed by two authors based on the following inclusion criteria: 1) published ‘meta-analysis’ or ‘systematic review and meta-analysis’ focused on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or non-randomized intervention studies; 2) mental health conditions (i.e., mental disorders and related symptoms) should be assessed using structured psychiatric diagnostic interviews, as well as validated or commonly used rating scales; 3) the research targeted university students; and 5) reported the summary effect size with 95 % confidence intervals (CI). In addition, studies that did not clearly describe the intervention were excluded. All disagreements between the two authors were discussed and resolved consistently. In addition, if several articles used the same population (from the same original study), only the most recent, complete, or largest study would be included in the review. However, if different meta-analyses report different results for that population, all of those results will be included in the omnibus review(Ioannidis, 2009).

Data extraction and quality assessmentTwo investigators (HH and HSF) independently extracted data from the studies, including the title, first author, publication year, number of included studies and participants, intervention, comparison, outcomes, and specific effect metrics (i.e., standardized mean difference (SMD; including Hedge's g and Cohen's d)) with 95 % CIs. Interventions in this umbrella review were classified into 4 categories: 1) mindfulness-based interventions; 2) exercise interventions; 3) cognitive and behavioural-related interventions; 4) other interventions (e.g., educational interventions, aromatherapy, animal-assisted interventions, and internet-based interventions).

The methodological quality of each included meta-analysis was assessed by applying AMSTAR 2. This 16-item tool rated the overall confidence of systematic review into 4 categories (high, moderate, low, and critically low) rather than deriving an overall score(Shea et al., 2017).

Data analysisThe summary effect estimate, its corresponding 95 % CIs and P value were recalculated using the random effects model of DerSimonian and Laird, as in previous umbrella reviews (Barbui et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2020). We conducted Cochran's Q tests and calculated the I2 statistic to detect heterogeneity between studies. P value<0.10 was considered significant for Cochran's Q test and I2>50 % indicated high heterogeneity (Ioannidis, Patsopoulos & Evangelou, 2007; WG, 1954). We also estimated the 95 % prediction interval, suggesting the range in which the effect estimate of a future study examining the same research question is expected to lie (Riley, Higgins & Deeks, 2011). Egger's regression asymmetry test was applied to assess publication bias (Egger, Davey Smith, Schneider & Minder, 1997). An Egger's P value<0.10 indicated the presence of small-study effects, which meant the small studies were more likely to give high-risk estimates and the effects estimate of large studies tended to be more conservative (Papadimitriou et al., 2021). The potential excess significance bias was evaluated to investigate whether the observed number of studies (O) with nominally statistically significant results (P<0.05) of each meta-analysis was different from the expected (E) (Ioannidis & Trikalinos, 2007). The expected number of significant results was calculated based on the sum of the statistical power estimates, with an algorithm from a non-central t distribution and a plausible effect size for the tested association, which was defined as the estimate of the largest study in each meta-analysis (J, 2013). P value<0.10 was considered as a statistical threshold of excess significance. All statistical analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (http://www.R-project.org, The R Foundation). The statistical tests were all two-tailed.

Certainty of evidenceWe determined the strength of evidence for each outcome included in the umbrella review in line with previous umbrella reviews (Gao et al., 2022; Papatheodorou, 2019). The approach categorized evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses into 5 classes: convincing evidence (class I), highly suggestive evidence (class II), suggestive evidence (class III), weak evidence (class IV), and no significant evidence (class V). Criteria for each level of evidence were as follows (Hermelink et al., 2022): 1) P values<10−6 under a random effects model, >1000 cases, I2<50 %, 95 % prediction interval excluding the null value, no small-study effect and no excess significance bias, 2) P values<10−6 under a random effects model, largest study with a statistically significant effect and criteria of class I not met, 3) >1000 cases, P values<10−3 under a random effects model and criteria of class I-II not met, 4) P value<0.05 under random-effects and criteria of class I-III not met, 5) P value≥0.05 under random-effects.

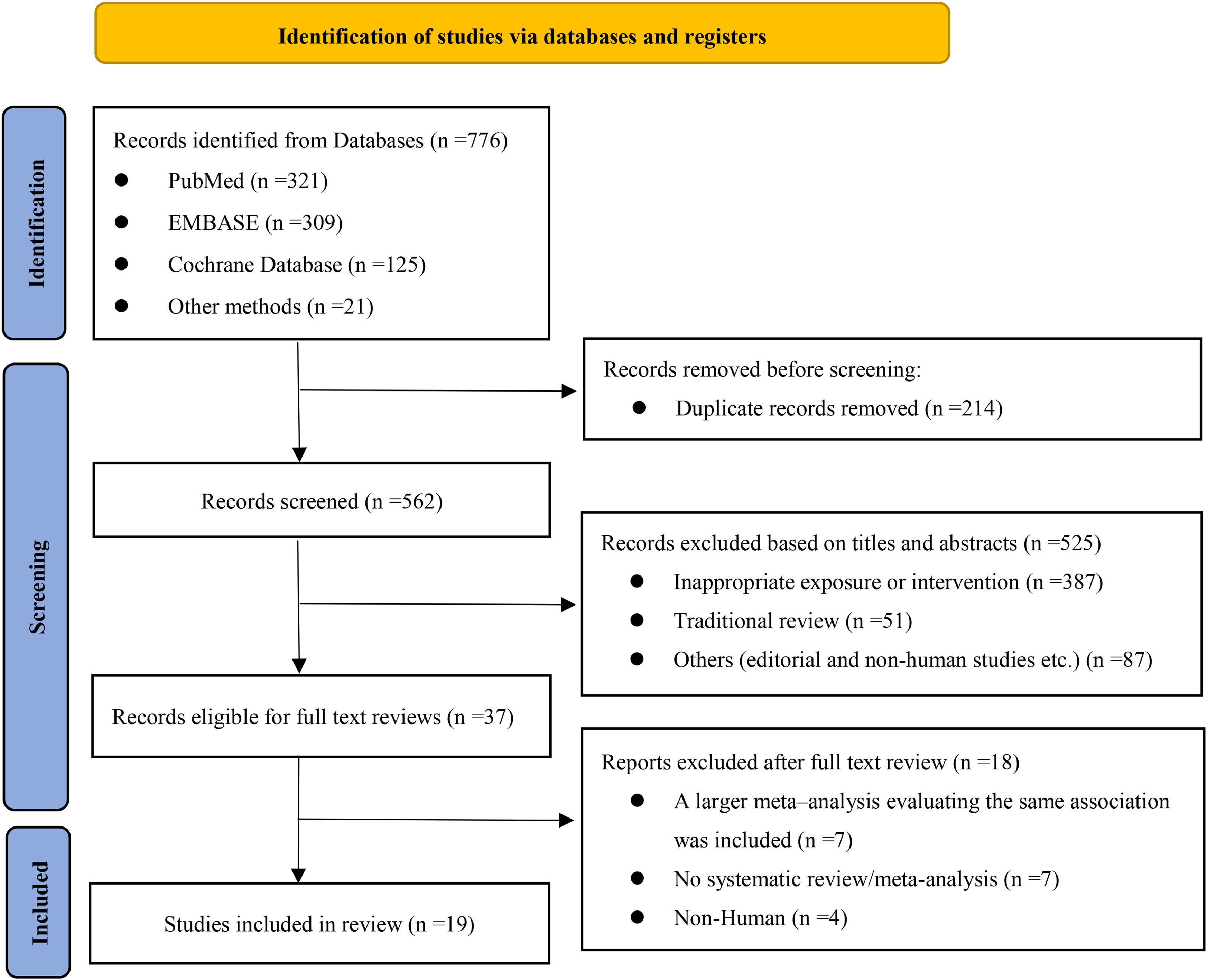

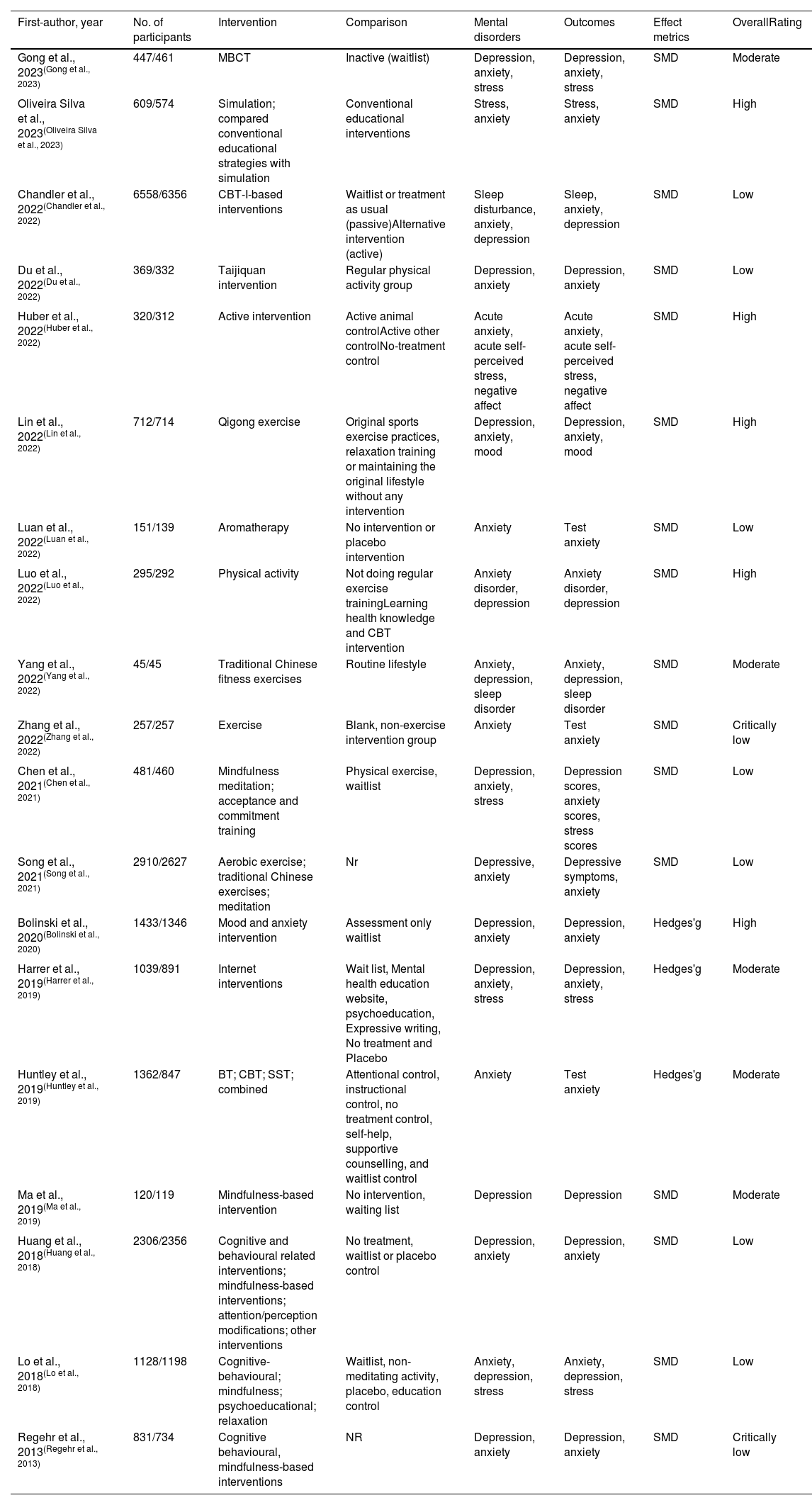

ResultsThe flowchart of the study selection process was shown in Fig. 1. The systematic search resulted in a total of 776 records. After the removal of duplicates and scanning of the titles and abstracts, 525 articles were excluded: 387 inappropriate intervention, 51 traditional reviews, 87 others (editorial and non-human studies, etc.), and 37 full-text articles were assessed for potential eligibility. Finally, 19 articles involving 74 meta-analyses met the umbrella review inclusion criteria and were eventually included for reanalysis. Table 1 shows the details of the included systematic reviews. The included reviews analysed intervention effects on university students with anxiety, depression or stress, respectively. Among these systematic reviews, 15 meta-analyses examined the effect of exercise-based interventions, 15 meta-analyses examined the effect of cognitive and behavioural-related interventions, 20meta-analyses assessed the effect of mindfulness-based interventions, and 24 meta-analyses assessed the effect of other interventions including educational-based interventions, Aromatherapy, animal-assisted interventions and international-based interventions.

Characterization and quality assessment of a qualified meta-analysis assessing the relationship between mental disorders and interventions for college students.

| First-author, year | No. of participants | Intervention | Comparison | Mental disorders | Outcomes | Effect metrics | OverallRating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gong et al., 2023(Gong et al., 2023) | 447/461 | MBCT | Inactive (waitlist) | Depression, anxiety, stress | Depression, anxiety, stress | SMD | Moderate |

| Oliveira Silva et al., 2023(Oliveira Silva et al., 2023) | 609/574 | Simulation; compared conventional educational strategies with simulation | Conventional educational interventions | Stress, anxiety | Stress, anxiety | SMD | High |

| Chandler et al., 2022(Chandler et al., 2022) | 6558/6356 | CBT-I-based interventions | Waitlist or treatment as usual (passive)Alternative intervention (active) | Sleep disturbance, anxiety, depression | Sleep, anxiety, depression | SMD | Low |

| Du et al., 2022(Du et al., 2022) | 369/332 | Taijiquan intervention | Regular physical activity group | Depression, anxiety | Depression, anxiety | SMD | Low |

| Huber et al., 2022(Huber et al., 2022) | 320/312 | Active intervention | Active animal controlActive other controlNo-treatment control | Acute anxiety, acute self-perceived stress, negative affect | Acute anxiety, acute self-perceived stress, negative affect | SMD | High |

| Lin et al., 2022(Lin et al., 2022) | 712/714 | Qigong exercise | Original sports exercise practices, relaxation training or maintaining the original lifestyle without any intervention | Depression, anxiety, mood | Depression, anxiety, mood | SMD | High |

| Luan et al., 2022(Luan et al., 2022) | 151/139 | Aromatherapy | No intervention or placebo intervention | Anxiety | Test anxiety | SMD | Low |

| Luo et al., 2022(Luo et al., 2022) | 295/292 | Physical activity | Not doing regular exercise trainingLearning health knowledge and CBT intervention | Anxiety disorder, depression | Anxiety disorder, depression | SMD | High |

| Yang et al., 2022(Yang et al., 2022) | 45/45 | Traditional Chinese fitness exercises | Routine lifestyle | Anxiety, depression, sleep disorder | Anxiety, depression, sleep disorder | SMD | Moderate |

| Zhang et al., 2022(Zhang et al., 2022) | 257/257 | Exercise | Blank, non-exercise intervention group | Anxiety | Test anxiety | SMD | Critically low |

| Chen et al., 2021(Chen et al., 2021) | 481/460 | Mindfulness meditation; acceptance and commitment training | Physical exercise, waitlist | Depression, anxiety, stress | Depression scores, anxiety scores, stress scores | SMD | Low |

| Song et al., 2021(Song et al., 2021) | 2910/2627 | Aerobic exercise; traditional Chinese exercises; meditation | Nr | Depressive, anxiety | Depressive symptoms, anxiety | SMD | Low |

| Bolinski et al., 2020(Bolinski et al., 2020) | 1433/1346 | Mood and anxiety intervention | Assessment only waitlist | Depression, anxiety | Depression, anxiety | Hedges'g | High |

| Harrer et al., 2019(Harrer et al., 2019) | 1039/891 | Internet interventions | Wait list, Mental health education website, psychoeducation, Expressive writing, No treatment and Placebo | Depression, anxiety, stress | Depression, anxiety, stress | Hedges'g | Moderate |

| Huntley et al., 2019(Huntley et al., 2019) | 1362/847 | BT; CBT; SST; combined | Attentional control, instructional control, no treatment control, self-help, supportive counselling, and waitlist control | Anxiety | Test anxiety | Hedges'g | Moderate |

| Ma et al., 2019(Ma et al., 2019) | 120/119 | Mindfulness-based intervention | No intervention, waiting list | Depression | Depression | SMD | Moderate |

| Huang et al., 2018(Huang et al., 2018) | 2306/2356 | Cognitive and behavioural related interventions; mindfulness-based interventions; attention/perception modifications; other interventions | No treatment, waitlist or placebo control | Depression, anxiety | Depression, anxiety | SMD | Low |

| Lo et al., 2018(Lo et al., 2018) | 1128/1198 | Cognitive-behavioural; mindfulness; psychoeducational; relaxation | Waitlist, non-meditating activity, placebo, education control | Anxiety, depression, stress | Anxiety, depression, stress | SMD | Low |

| Regehr et al., 2013(Regehr et al., 2013) | 831/734 | Cognitive behavioural, mindfulness-based interventions | NR | Depression, anxiety | Depression, anxiety | SMD | Critically low |

Abbreviation. MBCT, Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy; CBT-I, cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia; BT, behavior therapy; CBT, cognitive-behavioural therapy; SST, study skill training; NR, not reported; SMD, standardized mean difference.

Of the 19 included systematic reviews, 26 % (n = 5) (Bolinski et al., 2020; Huber et al., 2022; Lin et al., 2022; Luo, Zhang, Liu, Ma & Jennings, 2022; Oliveira Silva et al., 2023) studies were rated as “high”, 26 % (n = 5) (Gong et al., 2023) (Yang, Guo, Cheng & Zhang, 2022) (Harrer et al., 2019; Huntley et al., 2019; Ma, Zhang & Cui, 2019) as “moderate”, 37 % (n = 7) (Chandler et al., 2022; Du et al., 2022) (Chen et al., 2021; Lo et al., 2018; Luan et al., 2022) (Huang, Nigatu, Smail-Crevier, Zhang & Wang, 2018; Song, Liu, Huang, Wu & Tao, 2021) as “low” and 11 % (n = 2) (Regehr, Glancy & Pitts, 2013; Zhang, Li & Wang, 2022) as “critically low” quality with the AMSTAR2 scoring system. Supplementary Table 1 presented the details of the quality of each included study evaluated using the AMSTAR2 tool. The most frequent flaws for the low methodological quality reviews were as follows: the protocol of the systematic overview was not mentioned, no description of the study selection process and the data extraction process, the potential impact of risk of bias (RoB) was not assessed and the literature was not accounted for the RoB in individual studies when interpreting the results of the review, and publication bias was not examined or discussed.

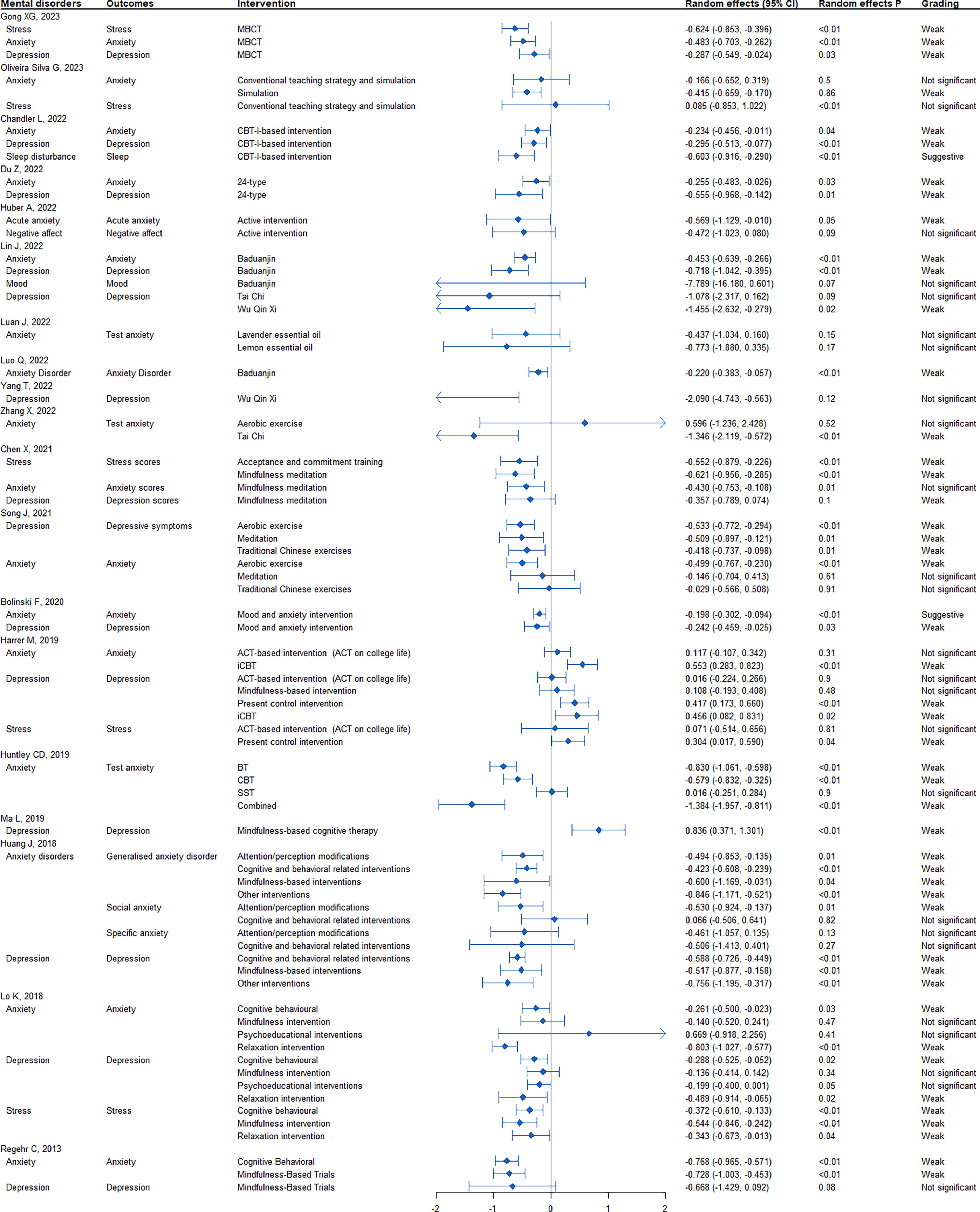

Exercise interventionA total of 15 meta-analyses assessed the effects of exercise interventions including Baduanjin, Taichi, Wuqinxi, traditional Chinese exercises, and aerobic exercise on mental illness, of which 7 (Du et al., 2022; Lin et al., 2022; Song et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2022) meta-analyses related to depression, 7(Du et al., 2022; Lin et al., 2022; Luo et al., 2022; Song et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2022) related to anxiety and 1(Lin et al., 2022) related to mood changes. 10 re-analyses were nominally statistically significant under random effects models (P<0.05), however, only one 95 % prediction interval excluded the null value. 73 % (n = 11) of the included meta-analyses had high heterogeneity (I2>50 %). Evidence of small-study effects bias was observed in 3 meta-analyses, and excess significance bias was detected in 10 meta-analyses. However, 8 meta-analyses consisted of less than 5 studies, in which case the power of the test would be reduced (Fig. 2 and Supplemental Table 2).

Efficacy of interventions for psychiatric disorders among university students with evidence grading. Note: Small study bias is considered positive if the p-value in Egger's test is less than 0.10. Excess significance bias is considered positive if the number of significant studies is greater than the expected number of significant studies (O>E) (based on the largest study with the smallest SE) and the p-value is less than 0.10. Abbreviations: MBCT mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, CBT-I cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia.

As for the strength of evidence, there is no meta-analysis presented convincing, highly suggestive, or suggestive evidence. 10 meta-analyses had weak evidence, indicating that exercise intervention could alleviate depression, including one meta-analyses item about Baduanjin (SMD: −0.718, P-random effects:<0.01) (Lin et al., 2022), one about Wuqinxi (SMD: −1.455, P-random effects: 0.02) (Lin et al., 2022) one about Tai Chi (SMD: −0.555, P-random effects: 0.01) (Du et al., 2022), one about traditional Chinese exercises and (SMD: −0.418, P-random effects: 0.01) (Song et al., 2021), and one about Aerobic Exercise (SMD: −0.533, P-random effects:<0.01) (Song et al., 2021). Weak evidence also indicated that exercise intervention could alleviate anxiety symptoms, including two meta-analyses items about Baduanjin (SMD: −0.453, P-random effects:<0.01 (Lin et al., 2022); and SMD: −0.220, P-random effects:<0.01 (Luo et al., 2022)), two about Tai Chi (SMD: −1.346, P-random effects:<0.01 (Zhang et al., 2022); and SMD: −0.255, P-random effects: 0.03 (Du et al., 2022)), and one about Aerobic Exercise (SMD: −0.499, P-random effects:<0.01 (Song et al., 2021)).

Cognitive behavioural intervention (CBI)A total of 15 meta-analyses assessed the effects of cognitive behavioural intervention on mental health problems including depression, anxiety, sleep disturbance, and stress. Overall 12 re-analyses reported a nominally statistically significant summary result using random effects models (P<0.05). The 95 % prediction interval excluded the null value in only two meta-analyses. There was significant heterogeneity (I2>50 %) in 33 % (n = 5) of the included meta-analyses. Evidence of small-study effects bias was noticed in two meta-analyses whereas excess of significance bias was observed in six meta-analyses. 7 meta-analyses consisted of less than 5 studies, suggesting the power of the test would be reduced (Fig. 2 and Supplemental Table 2).

Only one meta-analysis (Chandler et al., 2022) was supported by suggestive strength of the evidence that CBI has positive effects on sleep disturbance, with the SMD of −0.603 (95 % CI: −0.916, −0.290) and P-random effects<0.01. Strength of association was weak for nine meta-analyses, suggesting that CBI could reduce the risk of depression (SMD: −0.588 to −0.295, all P-random effects<0.01), anxiety (SMD: −0.768 to −0.234, P-random effects:<0.01–0.04; Hedges'g: −0.579 to −0.830, all P-random effects<0.01) and stress (SMD: −0.544 to −0.603, all P-random effects<0.01). In addition, 2 meta-analyses supported by weak evidence also indicated that there were CBI effects on depression and anxiety. The Hedges’ g was 0.456 (95 % CI:0.082, 0.831) for depression and 0.553 (95 % CI: 0.283,0.823) for anxiety, separately.

Mindfulness-based intervention (MBI)A total of 20 meta-analyses assessed the effect of a mindfulness-based intervention on mental health problems including depression, anxiety, and stress. Among these comparisons, 14 re-analyses were nominally statistically significant at P<0.05 under random effects models, and only two 95 % prediction intervals excluded the null value. About 25 % (n = 5) of the included meta-analyses that we re-analysed had high heterogeneity (I2>50 %). The risk of small-study effects bias was noticed in 1 comparison, and excess significance bias was verified for 6 comparisons. However, most comparisons (15/20) consisted of less than 5 studies, in which case the power of the test was reduced (Fig. 2 and Supplemental Table 2).

None of the 20 meta-analyses achieved convincing, highly suggestive, or suggestive strength of the evidence. In addition, the strength of the evidence was weak for meta-analyses, which showed that MBI could reduce the risk of anxiety (SMD: −0.803 to −0.483, P-random effects:<0.01–0.04), depression (SMD: −0.728 to −0.287, P-random effects:<0.01–0.03) and stress (SMD: −0.624 to −0.343, P-random effects:<0.01–0.04). Weak evidence also showed that MBI was effective for the prevention of depressive symptoms, with SMD (95 % CI) of 0.836 (0.371, 1.301).

Other interventionsA total of 24 meta-analyses assessed the effect of other interventions (i.e., educational interventions, simulation, aromatherapy, study skill training, acceptance, and commitment therapy, etc.) on mental health problems including depression, anxiety, and stress. 11 re-analyses reported a nominal statistically significant summary effect under random effects models (P<0.05), however, only two 95 % prediction interval excluded the null value. 46 % (n = 11) of the included meta-analyses had high heterogeneity (I2>50 %). The risk of small-study effects bias was noticed in three meta-analyses whereas the excess of significance bias was observed in eight meta-analyses. However, most meta-analyses (17/24) consisted of less than 5 studies, indicating the power of the test would be reduced (Fig. 2 and Supplemental Table 2).

A meta-analysis achieved suggestive strength of evidence suggesting that mood and anxiety intervention (MAI) had positive effects on anxiety (Hedges'g = −0.198, 95 % CI: −0.302, −0.094, P-random effects<0.01). Furthermore, 11 meta-analyses were supported by weak evidence, which suggested other interventions like simulation (SMD: −0.415, P-random effects: 0.86) (Oliveira Silva et al., 2023), present control intervention (Hedges'g: 0.417, P-random effects:<0.01) (Harrer et al., 2019), acceptance, commitment training (SMD: −0.552, P-random effects:<0.01) (Chen et al., 2021) and attention/perception modification (SMD: −0.530 to −0.494, P-random effects: 0.01) (Huang et al., 2018) could have effects on university students with mental health problems including depression, anxiety and stress.

DiscussionTo our knowledge, this study is the first umbrella review to comprehensively and quantitatively identify and evaluate the hierarchy of evidence for various types of interventions for university students with mental disorders. We included 19 published systematic reviews, which comprised 74 meta-analyses for the efficacy of different interventions for mental health outcomes including depression, anxiety, stress, and sleep disturbance. Overall, approximately 64 % (n = 47) of the included associations between interventions and mental disorders reported a nominally statistically significant summary random-effects estimate. 43 % (n = 32) associations represented large heterogeneity (I2>50 %). When the 95 % prediction intervals were calculated, which further indicated between-study heterogeneity, we found that the null value was excluded in only 9 % of the associations, this estimate could be explained by the low percentage of nominally significant meta-analyses. Furthermore, in about 12 % (n = 9) of the associations, the summary estimates were overestimated because of small study effects and in 41 % (n = 30) the observed number of studies with nominally statistically significant results in each meta-analysis was larger than expected, which implied that the results might have low power of test due to many meta-analyses with a small number of individual studies.

Our grading of the current evidence suggested that interventions based on exercise, CBI, MBI, and other interventions like MAI were effective while exercise intervention had the highest effect size for both depression and anxiety among university students. However, the strength of the efficacy and credibility of evidence was weak for most studies according to the umbrella review criteria. We found that the reduced confidence in the evidence could be attributed to the between-study heterogeneity, risk of excess significance bias, and prediction intervals including the null value, thus the reported associations need to be interpreted with caution.

It was suggested that contemporary university students are under pressure from study, life, job and family stressors, which were increasingly becoming the source of their psychological distress (Yang et al., 2022). Continuous stress and mental tension could trigger a range of unfavorable feelings and increase the risk of mental disorders such as anxiety and depression (Bonnet & Arand, 2000). The use of psychiatric medication was common among people with mental disorders. However, a significant number of side effects were frequently associated with medical treatment, which reduced treatment compliance and therefore negatively impacted the efficacy of the psychiatric medication (Carrascal-Laso et al., 2021; Lally & MacCabe, 2015). The findings of this umbrella review might provide an alternative or adjunctive treatment for disorders of this type. In this study, the efficacy of exercise intervention for depression and anxiety was supported by the strength of weak evidence. Despite the credibility of the estimate for this efficacy was not being optimal, it was worth conducting more high-quality randomized controlled trials to verify the effects of exercise interventions on various mental disorders. Previous studies examining the relationship between exercise and mental health have been widely conducted (Huang et al., 2021). The results of this review were in agreement with the previously published review suggesting that physical activity is one of the mainstay effective approaches in the management of depression, anxiety, and other mental health problems (Gao, 2022; Liu et al., 2021; Singh et al., 2023). Routine traditional fitness practice could alleviate fatigue and tension in the brain through the reduction of negative mood (Yang et al., 2022). The potential mechanism of exercise intervention contributing to alleviating severe anxiety and depression symptoms could be explained by the increased training of the middle cerebral cortex from exercises such as Qigong and Taichi, which has been shown to regulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, monoamine neurotransmitter, and adiponectin. Developing the habits of routine exercise would be beneficial for the promotion of physical and psychological health (Yeung, Chan, Cheung & Zou, 2018).

Moreover, the current umbrella review found suggestive evidence to support a moderate positive effect of cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) intervention on sleep disturbance among university students, which was in concert with previous studies looking at the effects of CBT for insomnia on sleep and even extend to mental health (Cheung, Jarrin, Ballot, Bharwani & Morin, 2019; Murawski, Wade, Plotnikoff, Lubans & Duncan, 2018). The development of insomnia is typically accompanied by depression, and often continuous following depression alleviated (Henry et al., 2021). Improvements in sleep quality could contribute to moderate improvements in mental health and improvements in insomnia have been observed to mediate the effects of depression using a CBT-I intervention (Henry et al., 2021; Scott, Webb, Martyn-St James, Rowse & Weich, 2021). It is hypothesized that CBI including sleep restriction therapy and stimulus management could boost slow-wave sleep, which was recognized as a disruption in both insomnia and depression, leading to increased homeostatic sleep drive (Krystal & Edinger, 2010; Staner, 2010). University students have the unique advantage of resources to utilize free services offered by university settings for counselling and intervention treatment of mental disorders, however, mental health problems are still high in this population. Sleep is rarely stigmatized way, thus universities can improve the condition by offering services through campus accommodation and/or university apps (Chandler et al., 2022). Additionally, we also found suggestive evidence that mood and anxiety intervention (MAI) has a small effect on anxiety. Notably, the evidence from a meta-analysis included only 4 individual studies. Therefore, the summary estimates might be inflated due to small study effects bias.

Mindfulness meditation is increasingly being included in mental health interventions, and our research shows weak evidence that mindfulness meditation can reduce the risk of anxiety and depression and prevent depressive symptoms. Mindfulness meditation training aims to help practitioners overcome depressive rumination by returning their attention to the present moment while eliminating rumination also reduces the emotional significance of the rumination thinking process, thereby reducing the risk of depression recurrence (Alsubaie et al., 2017). The effect of mindfulness meditation on anxiety is also to reduce repetitive negative thinking, similar to depression (Gu, Strauss, Bond & Cavanagh, 2015). After mindfulness meditation exercise, promotes top-down regulation of responsiveness to vague stimuli, leading to increased activation of brain regions important for emotional assessment and response (ventromedial PFC, ACC, and insula)(Goldin, Ziv, Jazaieri & Gross, 2012).

LimitationThe main limitations of this umbrella review are those of the included study, that is the limitations of the original meta-analyses. The most frequent flaws for the low methodological quality reviews, detected by AMSTAR2, were the absence of a protocol of the systematic overview, no description of the study selection process and the data extraction process, the potential impact of risk of bias (RoB) not assessed and absence of a thorough discussion of the RoB in individual studies when interpreting the results of the review, and publication bias were not examined or discussed.

Furthermore, we were not able to quantify the degree of mental disorders at a patient level, which could have minimized the between-study variability of the synthesized findings. We also did not analyze whether the efficacy of interventions is influenced by the type of inactive control, length of follow-up, type of provider, or other clinical or social-related variables. However, we have minimized potential bias using methodological approaches recommended by the available guidelines for evidence-based reviews.

Despite we searched major databases and additional sources to retrieve relevant literature, we could not include unpublished articles and those not published in the major databases. This potential exclusion of studies that could meet our criteria may inevitably result in publication bias. Finally, this umbrella study encompassed the meta-analyses conducted on university students, they are not representative of all sections of the overall population with mental disorders.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, this umbrella review provides preliminary evidence of the effectiveness of different non-pharmacological interventions on university students with mental disorders. However, these results should be interpreted carefully since heterogeneity was high. Future high-quality studies are necessary to confirm more convincing evidence of the potential effects of non-pharmacological interventions in the prevention and control of mental disorders.

FundingThe 2022 Guangdong Provincial National Defense Education Project "Research on the National Defense Education System for Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan Overseas Chinese Students in Mainland Universities from the Perspective of the Overall National Security Perspective" by the Guangdong Federation of Social Sciences and the Guangdong Provincial Association of National Defense Education (SL22ZD01); Fundamental Research Funds for Central Universities in 2022 "Research on the influencing factors of scientific and technological security of Jinan University" (21622801); School level Teaching Quality and Teaching Reform Project of Jinan University "Reform and Practice of Teaching Military Theory Courses in Colleges and Universities Characterized by overseas Chinese in the New Era." (JG2022122).

Data availabilityAll data included in this study were extracted from publicly available systematic reviews.

CRediT authorship contribution statementWT and XY designed the study. HH and HSF performed the searches and data extraction. CSY analyzed the data. HH and HSF drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed and approved the manuscript.

E) (based on the largest study with the smallest SE) and the p-value is less than 0.10. Abbreviations: MBCT mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, CBT-I cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia.' title='Efficacy of interventions for psychiatric disorders among university students with evidence grading. Note: Small study bias is considered positive if the p-value in Egger's test is less than 0.10. Excess significance bias is considered positive if the number of significant studies is greater than the expected number of significant studies (O>E) (based on the largest study with the smallest SE) and the p-value is less than 0.10. Abbreviations: MBCT mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, CBT-I cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia.'/>

E) (based on the largest study with the smallest SE) and the p-value is less than 0.10. Abbreviations: MBCT mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, CBT-I cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia.' title='Efficacy of interventions for psychiatric disorders among university students with evidence grading. Note: Small study bias is considered positive if the p-value in Egger's test is less than 0.10. Excess significance bias is considered positive if the number of significant studies is greater than the expected number of significant studies (O>E) (based on the largest study with the smallest SE) and the p-value is less than 0.10. Abbreviations: MBCT mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, CBT-I cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia.'/>