Research has highlighted the role of neuroticism, rumination, and depression in predicting suicidal thoughts, but studies on how these variables interplay are scarce. The aims of the present study were to test a model in which emotional stability (i.e., low neuroticism) would act as an antecedent and moderator of rumination and depressed mood in the prediction of suicidal ideation (i.e., moderated serial-mediation), and to explore their replicability across four countries and sex, among college students as an at-risk-group for suicide.

MethodParticipants were 3482 undergraduates from U.S, Spain, Argentina, and the Netherlands. Path analysis and multi-group analysis were conducted.

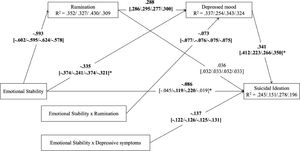

ResultsEmotional stability was indirectly linked to suicidal ideation via rumination and depressed mood. Moreover, emotional stability moderated the associations between rumination and depressed mood, and between depressed mood and suicidal ideation. Findings were consistent in males and females, and across countries studied.

DiscussionRegardless of sex and country, people with low emotional stability reported higher levels of rumination, which in turn was associated with more depressed mood, and these were associated with higher reports of suicidal thoughts. This cascade of psychological risk factors for suicidal ideation seems to be more harmful in people who endorse low levels of emotional stability.

Globally, nearly 800,000 people die by suicide annually (WHO, 2019). Death by suicide is the second leading cause of death in youths aged 15-29 years worldwide, so its prevention constitutes a high priority for public health policies (WHO, 2019). Within this age range, college students are considered an at-risk population due to their high rates of suicidal thoughts and behaviors, with about one out of four of them having experienced some form of suicidal ideation (Mortier et al., 2018). A key component for the development of prevention strategies is greater understanding of the factors involved in suicidality (WHO, 2014), with special attention to the study of suicidal ideation as the most prevalent expression of suicidality (Castellví et al., 2017; Franklin et al., 2017).

The causes of suicidality are presumed to be the result of the complex interplay between many different biological, psychological, and environmental factors (Joiner et al., 2005; O'Connor & Nock, 2014). Among the most studied psychological factors are psychopathology conditions such as depression, cognitive factors such as rumination, and personality traits such as neuroticism. Research has highlighted mood disorders as one of the main risk factors of suicidal behaviors in both young people and adults (e.g., Gili et al., 2019; San Too et al., 2019), although meta-analyses of longitudinal studies have reported weaker associations than expected (Franklin et al., 2017; Gili et al., 2019; Ribeiro et al., 2018). Thus, researchers have highlighted the need for the simultaneous consideration of many other factors beyond depression in order to increase the predictive power on suicidality research.

Rumination constitutes another widely studied risk factor for both depression and suicidal ideation. Rumination is defined as a style of thinking that involves repetitively and passively focusing on symptoms of depression, and the possible causes and consequences of these symptoms (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991), and is considered a key psychological process for explaining the onset and maintenance of depression (McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2011; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). Accordingly, different meta-analyses have reported moderate to high effects among the association between rumination and depression (Olatunji et al., 2013; Rood et al., 2009). In addition, rumination has shown associations to other conditions beyond depression (Aldao et al., 2010; Watkins & Roberts, 2020), including suicidal thoughts and behaviors (Morrison & O'Connor, 2008; Rogers & Joiner, 2017).

Last, one of the most important factors for understanding common mental disorders is neuroticism (Lahey, 2009; Ormel et al., 2013; Widiger & Oltmanns, 2017). Neuroticism is conceptualized as a basic dimension of personality that leads to individual differences on a continuum from emotional stability to high negative affect (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1985; Tackett & Lahey, 2017). Research has confirmed the strong associations of neuroticism with internalizing psychopathology, such as mood and anxiety disorders (Hakulinen et al., 2015; Jeronimus et al., 2016; Kotov et al., 2010) and to a lesser extent, with suicidal thoughts (Brandes & Tacket, 2019; Brezo et al., 2006). In addition, neuroticism/negative affect has also been proposed to be etiologically involved in the development of rumination (Hyde et al., 2008; Sachs-Ericsson et al., 2014; Shaw et al., 2019), so rumination has usually been considered as a mediator between neuroticism and depression (e.g., Barnhofer & Chittka, 2010; Kuyken et al., 2006; Lyon et al., 2021; Roelofs et al., 2008).

Neuroticism has not only been considered as an antecedent but also as a moderator of several risk factors for psychopathology. Thus, and from a classical model of diathesis-stress, neuroticism has been conceptualized as a vulnerability personality trait that would interact with stressful events, and other adverse factors, by exacerbating its effects on depression and other emotional disorders (Barlow et al, 2014; Vittengl, 2017). This differential reactivity to stressors may be explained, in part, because neuroticism would influence the selection of behavioral and cognitive coping strategies, and also moderated their effectiveness in managing distress and negative emotions (Bolger & Schilling, 1991; Bolger & Zuckerman, 1995). Claridge and Davis (2001) have also highlighted the moderating role of neuroticism but in a broader way, suggesting that it would act as a nonspecific moderator that would potentiate negative features of the individual in general, leading to maladaptive and unhealthy behaviors.

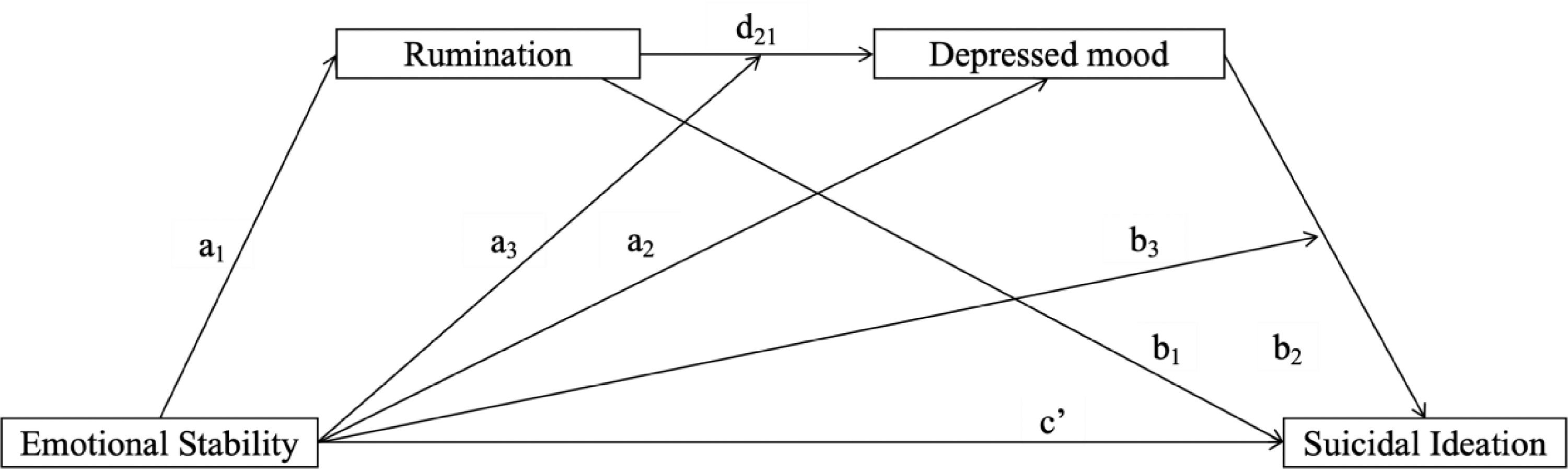

In summary, prior research suggests that: (1) depression is one of the strongest antecedents of suicidal ideation; (2) rumination is a cognitive antecedent for depression, and suicidal ideation; (3) neuroticism is associated with rumination, depression, and suicidal ideation; and (4) neuroticism may moderate the harmful effect of risk factors on depression and other related conditions. While independently examined, the simultaneous role of these psychological risk factors on suicidal ideation has limited research. Thus, the main aim of the present study was to clarify the interplay between these risk factors on suicidal ideation in a single model. Specifically, we hypothesized that emotional stability (i.e., low neuroticism) would be indirectly associated with suicidal ideation via rumination and depressive symptoms (i.e., emotional stability → rumination → depressive symptoms → suicidal ideation). Furthermore, we also hypothesized that the effects of rumination on depressive symptoms, and of depressive symptoms on suicidal ideation, would be stronger in students with higher levels of neuroticism (i.e., moderation). Finally, to explore the robustness of the hypothesized model, we tested its invariance in four countries (United States, Spain, Argentina and the Netherlands) and across sex groups.

Materials & methodsParticipants and procedureCollege students (n = 3482) from the U.S., Spain, Argentina, Uruguay, and the Netherlands participated in an online cross-sectional survey study exploring risk and protective factors of marijuana use and mental health outcomes (see Bravo et al., 2019). Study procedures were approved by the institutional review boards (or their international equivalent) at the participating universities. Due to low sample size, students from Uruguay were excluded from the present analyses. Only data from students that completed measures about depressive symptoms, rumination, suicidal ideation, and neuroticism were included in the final analysis (U.S., n = 1774; Spain, n = 688; Argentina, n = 352; the Netherlands, n = 286). An over-representation of female students was observed in the final samples (U.S., 67.1%; Spain, 66.1%; Argentina, 65.6%; the Netherlands, 74.8%). Participants' mean age ranged from 20.05 to 24.26 years across countries.

InstrumentsSuicidal ideation and depressed moodWe used the scales of suicidal ideation and depressed mood (assessed by one and two items, respectively) of the DSM-5 Self-rated Level 1 Cross-Cutting Symptom Measure (APA, 2013; Spanish version, APA, 2014), measured on a 5-point response scale (0, none or not at all; 4, severe or nearly every day) during the last two weeks. This scale has been validated among college-student populations (Bravo et al., 2018b).

RuminationRumination was assessed using the 15-item version of the Ruminative Thought Style Questionnaire (RTSQ; Tanner et al., 2013; Spanish version, Bravo et al., 2018a), in which participants respond to what extent the items described them on the basis of a 7-point scale (1, Not at all; 7, Very Well). The RTSQ has shown evidence of reliability and validity among undergraduate students and over time, both in English and Spanish speakers (Bravo et al., 2018a;Vidal-Arenas et al., 2022).

Emotional StabilityThe dimension of Emotional Stability-Neuroticism was measured with the Big Five Personality Trait Short Questionnaire (BFPTSQ; Morizot, 2014; Spanish version, Ortet et al., 2017) which is comprised of 10 items in which participants respond to what extent the items described them on the basis of a 5-point response scale (0, disagree strongly; 4, agree strongly). The BFPTSQ has shown evidence of reliability and validity among undergraduate students, both in English and Spanish speakers (Mezquita et al., 2019).

Data AnalysisTo test the proposed model (see Fig. 1) a path analysis was carried out using Mplus 8.4, and age and sex were entered as covariates. Overall model fit was evaluated following criteria proposed by Marsh et al. (2004), including the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI; > .90 [acceptable], > .95 [optimal]), Comparative Fit Index (CFI; > .90 [acceptable], > .95 [optimal]), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; < .06). Also, multi-group analyses were run to test the model invariance across countries and sex groups. We used model comparison criteria of ΔCFI/ΔTFI ≥ .01 (i.e., decrease indicates worse fit; Cheung & Rensvold, 2002) and ΔRMSEA ≥ .015 (i.e., increase indicates worse fit; Chen, 2007) to consider the tested model as invariant. We also examined the total, indirect and direct effects of each predictor on suicidal ideation using bias-corrected bootstrapped estimates (Efron & Tibshirani, 1993) based on 10,000 bootstrapped samples. To determine statistical significance, 99% bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals not containing zero were evaluated.

ResultsBivariate and descriptive statistics are summarized in Supplemental Table 1 and Supplemental Table 2. https://osf.io/a2s7x/?view_only=e721b50f95554c5b8a3e4d7c00ec97a5

Hypothesized modelThe hypothesized model with the whole sample showed optimal fit indices (see Table 1).

Invariance testing results of the path analysis across countries and sex.

| Moderated serial mediation model | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Fit Indices | ||||||||||||

| X2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA (90% C.I) | ||||||||

| M.1 | Hypothesized Model | 7.000* | 2 | .999 | .986 | .029 (.008, .053) | ||||||

| Moderated serial mediation model across countries | ||||||||||||

| Overall Fit Indices | Comparison Fit Indices | |||||||||||

| X2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA (90% C.I) | Model comparison | ΔX2 | ΔCFI | ΔTLI | ΔRMSEA | |||

| MG1 | Unconstrained Model | 18.355* | 8 | .998 | .973 | .041 (.016, .066) | — | — | — | — | — | |

| MG2 | Full Constrained Model | 197.388** | 83 | .978 | .971 | .042 (.035, .050) | MG2 vs MG1 | 179.033** | -.020 | -.002 | .001 | |

| MG3 | Full Constrained Model less Constraint 5 | 183.282** | 80 | .980 | .973 | .041 (.033, .049) | MG3 vs MG1 | 164.927** | -.018 | .000 | .000 | |

| MG4 | Full Constrained Model less Constraint 5/11 | 167.372** | 77 | .983 | .976 | .039 (.031, .047) | MG4 vs MG1 | 149.017** | -.015 | .003 | -.002 | |

| MG5 | Full Constrained Model less Constraint 5/11/1 | 153.745** | 74 | .985 | .978 | .037 (.029, .046) | MG5 vs MG1 | 135.390** | -.013 | .005 | -.004 | |

| MG6 | Full Constrained Model less Constraint 5/11/1/9 | 141.396** | 71 | .986 | .979 | .036 (.027, .044) | MG6 vs MG1 | 123.041** | -.012 | .006 | -.005 | |

| MG7 | Full Constrained Model less Constraint 5/11/1/9/14 | 129.895** | 68 | .988 | .981 | .034 (.025, .043) | MG7 vs MG1 | 111.540** | -.010 | .008 | -.007 | |

| MG8 | Full Constrained Model less Constraint 5/ 11/1/9/14/3 | 120.025** | 65 | .989 | .982 | .033 (.024, .042) | MG8 vs MG1 | 101.670** | -.009 | .009 | -.008 | |

| Moderated serial mediation model across sex | ||||||||||||

| Overall Fit Indices | Comparison Fit Indices | |||||||||||

| X2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA (90% C.I) | Model comparison | ΔX2 | ΔCFI | ΔTLI | ΔRMSEA | |||

| MG1B | Unconstrained Model | 8.900 | 4 | .999 | .989 | .028 (.000, .053) | ||||||

| MG2B | Full Constrained Model | 44.727* | 23 | .995 | .992 | .025 (.014, .035) | MG2B vs MG1B | 35.827* | -.004 | .003 | -.003 | |

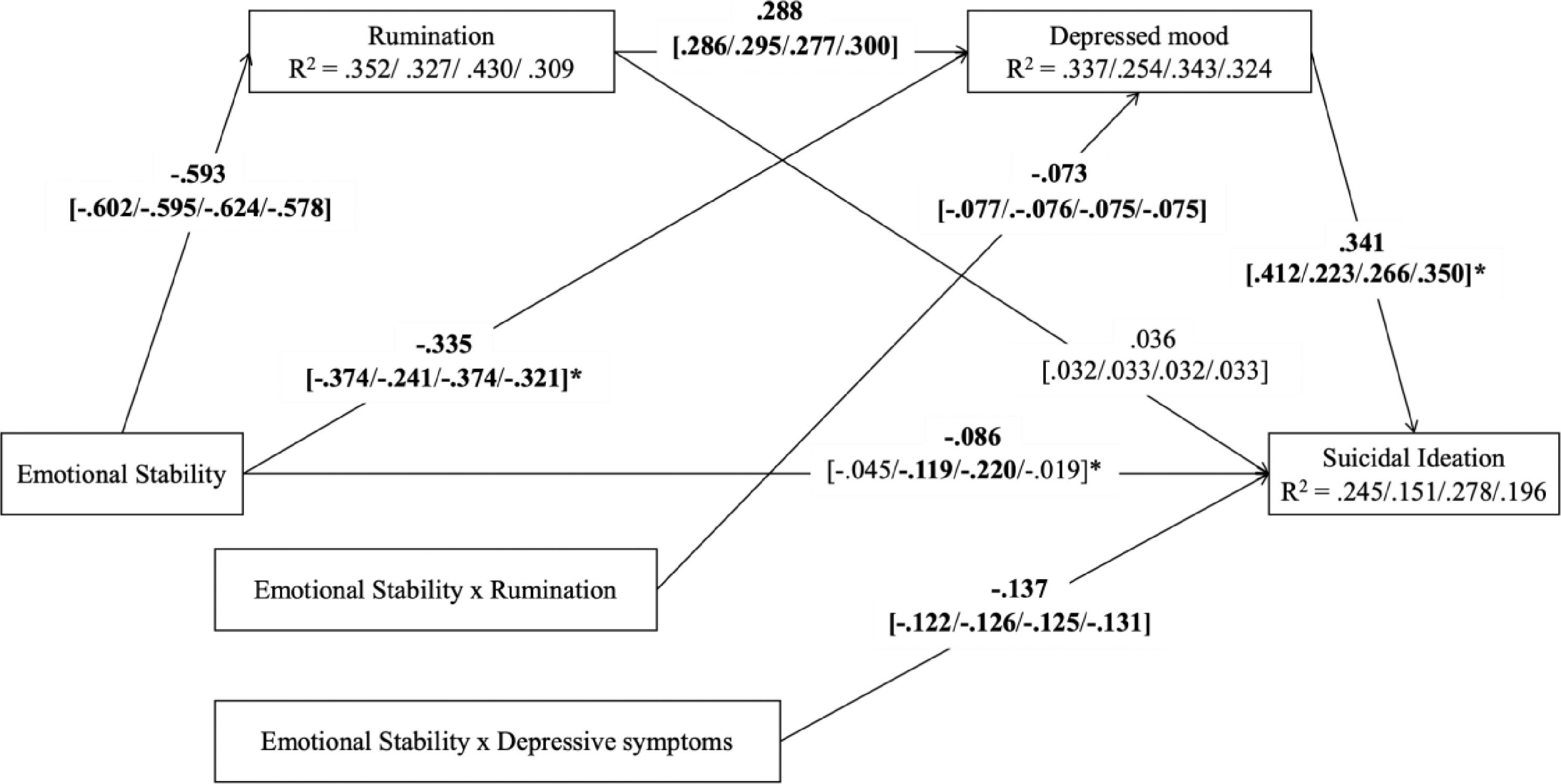

The indirect and total effects are presented in Table 2, and direct effects are presented in Fig. 2. Within our model, there was a significant serial mediation effect from emotional stability to suicidal ideation via rumination and depressed mood. Specifically, low emotional stability was significantly associated with higher rumination, which in turn was associated with higher depressed mood, which in turn related to higher endorsement of suicidal ideation. Also, the effect from emotional stability to suicidal ideation was mediated by depressed mood, as well as the effects from rumination to suicidal ideation were mediated via depressed mood. Finally, the associations between rumination and depressed mood, and also between depressed mood and suicidal ideation, were significantly moderated by emotional stability. Specifically, the effects from rumination to depressed mood, and from depressed mood to suicidal ideation, were stronger among those who reported lower levels of emotional stability.

Summary of indirect and total effects (M.1).

Note: Bold type indicates significant effects (i.e., 99% bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals not containing zero).

Depicts estimates of tested model within the total sample (M.1) and by countries (MG8).

The fit indices for multi-group analysis were adequate (see Table 1, MG1). However, the initial comparative fit indices with the fully constrained model suggested differences across countries (MG2; i.e., ΔCFI/ΔTFI ≥ .01, ΔRMSEA ≥ .015). In order to find an invariant model, we iteratively identified freely estimated paths with the highest contribution to non-invariance of the model, until we obtained an adequate fit (see Table 1, MG8). As a result, six paths were freely estimated (i.e., not constrained across countries), but only three of them were related to the hypothesized model (i.e., depressed mood → suicidal ideation; emotional stability → suicidal ideation; emotional stability → depressed mood). When we examined these three paths for each country (see Fig. 2, and Supplemental Table 3), two of them remained significant (i.e., 99% bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals not containing zero) in all the four countries, although we observed some differences regarding the size of the magnitude between countries (i.e., depressed mood →suicidal ideation; emotional stability→ depressed mood; see Fig. 2). The only relevant difference between countries was observed in the direct path from emotional stability to suicidal ideation, which was significant in Spain (β = -.119) and Argentina (β = -.220), but not in the United States (β = -.045) or the Netherlands (β = -.019).

Model invariance across sex groupsFinally, the invariance of the hypothesized model across sex was tested. The multi-group analysis showed adequate fit indices (see Table 1, MG1B). When we constrained the paths of the two groups (MG2B), this resulted in a ΔCFI/ΔTFI ≤ .01, ΔRMSEA ≤ .015. Therefore, the model can be considered invariant across sex.

DiscussionThe aim of the present study was to examine how important psychological risk-factors (i.e., emotional stability, rumination, and depressed mood) interplay in the etiology of suicidal ideation. Specifically, we proposed a path model in which we tested (1) the indirect effects from emotional stability to suicidal ideation via rumination and depressed mood; and (2) the moderating effects of emotional stability on associations between rumination, depressed mood, and suicidal ideation. Our findings supported a serial mediation model in which low levels of emotional stability were associated with high levels of rumination, which in turn were related to higher depressed mood, and these were associated with the presence of more suicidal thoughts. Moreover, the findings also showed that these serial effects were more harmful (i.e., stronger) at lower levels of emotional stability, such that individuals with low levels of emotional stability are highly sensitive to the negative effects of rumination and depressed mood compared to those with high levels of emotional stability. Importantly, the proposed model was invariant across sex groups, and despite the observed slight differences in the magnitude of three paths between countries, the moderated serial-mediation model was virtually replicated across the four countries examined, supporting the robustness of our findings regardless of sex and sociocultural context.

Regarding mediation effects, depression has been considered an antecedent to suicidal ideation (O'Connor & Nock, 2014), but also a consequence of rumination (McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2011; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008), which suggests that depression could act as a mediator between rumination and suicidal thoughts. Accordingly, our findings indicated that depressed mood fully mediated the association between rumination and suicidal ideation (i.e., no statistically significant direct effects between rumination and suicidal ideation remained), a full mediation effect was replicated in the four countries studied, and across sex. The scarce research on this topic has reported similar indirect effects from rumination to suicidal ideation through depression (Chan et al., 2009; Miranda & Nolen-Hoeksma, 2007; Polanco-Roman et al., 2016), supporting the notion that rumination is linked to suicidal ideation through its effect on depressed mood.

Regarding the mediational role of rumination in the association between neuroticism and depression, our findings have shown a robust partial mediation effect from emotional stability to depressed mood through rumination in the four countries studied and across sex groups, in line with previous studies (e.g., Barnhofer & Chittka, 2010; Kuyken et al., 2006; Lyon et al., 2021; Roelofs et al., 2008; Smith et al., 2018; Whisman et al., 2020). Thus, neuroticism would influence depressed mood indirectly through rumination, but also directly, as a recent genetically informative study demonstrated, showing common but also specific influences of both neuroticism and rumination on depression symptoms (Du Pont et al., 2019).

In addition, our serial mediation model showed that emotional stability indirectly predicted suicidal ideation through rumination and depressed mood, but also presented a significant direct path to suicidal ideation. This effect, however, was small and it was not fully replicated across countries. In this regard, some previous studies have reported findings that may suggest a “complete” mediational effect of depression in the association between neuroticism/negative affect and suicidal ideation (Morales-Vives & Dueñas, 2018; Naragon-Gainey & Watson, 2011), whereas others suggest “partial” mediation effects (Rappaport et al., 2017; Statham et al., 1998). Thus, the inconsistencies found in the present, and past studies, advocate for further research in order to determine the conditions in which neuroticism could influence suicidal thoughts beyond rumination and depression.

Finally, we found that the personality dimension of emotional stability not only may act as an antecedent of rumination and depressed mood, but also moderated the effects from rumination to depressed mood and from depressed mood to suicidal ideation. Although the effect sizes of these interactions were small, they were replicated across the four countries studied, and across sex. Similar interactive effects have been previously described between negative affect and rumination in predicting depression symptoms and suicidal ideation (Zvolensky et al., 2016), and non-suicidal self-injury (Nicolai et al., 2016). In addition, research has also documented interactive effects of neuroticism with other psychological variables, such as cognitive strategies (Ng & Diener, 2009), mindfulness (e.g., Drake et al., 2017; Feltman et al., 2009), or ideal-self discrepancy (Hong et al., 2013; Wasylkiw et al., 2010) when predicting depression, psychological distress, and low well-being. Taken together, these findings would support that neuroticism may act as a moderator variable that would exacerbate the negative effect of other risk factors on depressed mood and related psychopathological conditions, in line with previous theoretical proposals (Barlow et al., 2014; Bolger & Zuckerman, 1995; Claridge & Davis, 2001).

It is important to mention the limitations of the present study. First, the Self-Rated Level-1 Cross-cutting measure from the DSM-5 uses two and one items to assess depressed mood and suicidal ideation, respectively. Despite this, these scales have shown good test-retest reliability, strong convergent validity with longer analogue measures (Bravo et al., 2018b), and association magnitudes found in present study are very similar to those obtained in other studies that used longer scales (e.g., Morales-Vives & Dueñas, 2018). Second, this study utilized a cross-sectional design, therefore longitudinal studies are needed to more properly assess directional/temporal relations. A third limitation has to do with the extent to which the results found in college students can be generalized to other populations (e.g., clinical populations). The depressed mood variable used does not necessarily equate to a major depressive episode, so the generalizability of present results to clinical depression should be made with caution. Finally, given that suicidality includes distinct components (i.e., suicidal thoughts, planning, and attempt), our findings circumscribe to suicidal ideation and cannot be extrapolated to other types of suicidal behaviors (Klonsky et al., 2018).

ConclusionBearing in mind these limitations, we posit our findings may be relevant at a theoretical and at an applied level. At a conceptual level, the proposed moderated serial mediation model may help to clarify the complex interplay between neuroticism, rumination, and depressed mood in the prediction of one of the most prevalent components of suicidal behavior (i.e., suicidal ideation). Specifically, our findings highlight the importance of the neuroticism, since (1) it is a key antecedent of rumination and depressed mood that, in turn, predicts suicidal ideation, and (2) it exacerbates the negative effects of risk factors on mental health, such as rumination on depressed mood, and depressed mood on suicidal ideation. Importantly, these findings were replicated in the four countries studied, increasing confidence about the robustness of the described effects. At an applied level, the present work highlights the importance of neuroticism and rumination for preventive actions and targeted interventions. Thus, a screening of neuroticism and rumination may help to identify those persons that are potentially at a high risk for depressed mood and suicidality and would be informative of those persons who would require specific, higher treatment dosages (Ormel et al., 2013; Tackett & Lahey, 2017). In addition, our results would support the notion that the combination of targeted interventions for neuroticism (Barlow et al., 2014; Sauer-Zavala et al., 2017) and rumination (Watkins & Roberts, 2020) could be especially beneficial in preventing depression and suicidal thoughts.

Data Availability StatementData is available at https://osf.io/a2s7x/?view_only=e721b50f95554c5b8a3e4d7c00ec97a5

Verónica Vidal-Arenas has been supported by a grant from Universitat Jaume I (PREDOC/18/12). This study was also supported by grants UJI-A2019-08 from Universitat Jaume I, AICO/ 2019/197 from the Valencian Autonomous Government, and RTI2018-099800-B-I00 from the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities (MICIU/ FEDER) in Spain. Dr. Bravo was supported by a training grant (T32-AA018108) from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) in the United States during the duration of data collection for this project. Data collection was supported, in part, by grant T32-AA018108. NIAAA had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication. This study was supported by grants from the National Secretariat of Science and Technology (FONCYT, grant number #PICT 2015-849), and by grants from the Secretariat of Science and Technology- National University of Córdoba (SECyT-UNC) in Argentina.

This project was completed by the Cross-cultural Addictions Study Team (CAST, castresearcher@gmail.com), which includes the following investigators (in alphabetical order): Adrian J. Bravo, William & Mary, USA (Coordinating PI); James M. Henson, Old Dominion University, USA; Manuel I. Ibáñez, Universitat Jaume I de Castelló, Spain; Laura Mezquita, Universitat Jaume I de Castelló, Spain; Generós Ortet, Universitat Jaume I de Castelló, Spain; Matthew R. Pearson, University of New Mexico, USA; Angelina Pilatti, National University of Cordoba, Argentina; Mark A. Prince, Colorado State University, USA; Jennifer P. Read, University at Buffalo, USA; Hendrik G. Roozen, University of New Mexico, USA; Paul Ruiz, Universidad de la República, Uruguay.