It is not rare that intensive care unit (ICU) patients report unusual subjective experiences, ranging from a feeling of harmony with the environment to complex phenomena such as near-death experience (NDE). This 1-year follow-up study investigates the characteristics and potential global impact of the NDE memories recalled by ICU survivors.

MethodWe prospectively enrolled 126 adult survivors of a prolonged (>7days) ICU stay (all etiologies), including 19 (15 %) who reported a NDE as identified by the Greyson NDE scale. The NDE group underwent a semi-structured interview one month later evaluating their memory characteristics and the associated life-threatening situation. One year after inclusion, all patients (regardless of whether they recalled an NDE) were contacted for a follow-up Greyson NDE scale assessment and questions about their ICU experience and opinions on death since discharge.

ResultsThe Greyson NDE scale revealed that the most frequently reported features were altered time perception, heightened senses and life review, and the Greyson total scores did not evolve over time. NDE memories persisted, with a consequent number of phenomenological characteristics (e.g., visual details, emotions). One year post-ICU, two patients (18 %) of the NDE group and 12 (24 %) of the non-NDE group were less afraid of death.

ConclusionsResults emphasize the clinical importance of interviewing all ICU patients to explore any memory after an ICU stay.

There has been a recent growing number of anecdotal reports of unusual subjective experiences in critical medical situations, which can range from a mere feeling of harmony with the environment to more intense or complex hallucinatory experiences such as out-of-body experiences or seeing deceased relatives. When the subjective experience contains specific features, as described by the Greyson NDE scale (Greyson, 1983) or by its recent adaptation the Near-Death Experience Content scale (Martial et al., 2020a), it qualifies as a near-death experience (NDE). NDEs can be defined as episodes of disconnected consciousness, namely episodes of internal awareness during a period of unresponsiveness, that typically occur in critical, potentially life-threatening conditions (Martial et al., 2020b). The few studies that have investigated the impact of these experiences across different contexts demonstrate significant acute and enduring changes in attitudes and behaviors (e.g., Bianco et al., 2019; Groth-Marnat and Summers, 1998; Pehlivanova et al., 2023; Sweeney et al., 2022), however, the impact of such experiences on intensive care unit (ICU) survivors specifically remains unknown. This underscores the necessity for healthcare professionals to be knowledgeable about such phenomena.

Following a few pioneer prospective studies aiming to detect NDE in cardiac arrest (Greyson, 2003; Parnia et al., 2014, 2023; Schwaninger et al., 2002; van Lommel et al., 2001) and traumatic brain injury (Hou et al., 2013) survivors, last year was published the first prospective study carried out in patients who survived a critical illness, regardless of etiologies (Rousseau et al., 2023). We revealed that 15 % of the sample (19 out of 126 included survivors) reported having had an NDE. Several factors were associated to their emergence, such as mechanical ventilation, the presence of sedation and analgesia, and the dissociative and spiritual propensities, with the two latter emerging as predictors of the NDE recall. A significant finding of this research is that these episodes of disconnected consciousness are not uncommonly reported by ICU survivors. Nonetheless, so far, very little is known about the potential consequences of experiencing a NDE in critical conditions that result in an ICU admission. This present article reports the results of the different follow-up interviews (1-month and 1-year post-ICU stay) of the cohort of ICU survivors enrolled in Rousseau et al. (2023), aiming to characterize the memory of their ICU stay (including the NDE memory for those who reported one) as well as potential enduring consequences on lifestyle, well-being, worldviews, and beliefs.

Material and methodsPopulation and procedureThis study is a part of the wider prospective and monocentric study aiming to investigate the incidence of NDE in ICU survivors as well as the factors that may influence its occurrence. The study design and methodological details have been reported elsewhere (Rousseau et al., 2023). To put it succinctly, between July 2019 and March 2020, all patients who were discharged from the five ICUs of our hospital after a prolonged stay (i.e., >7 days), whatever the etiology, were screened. Initial exclusion criteria were: <18 years old, non-French speaking, refusal to participate, confusion or delirium detected by the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM; Inouye et al., 1990) instrument, and early (i.e., <7 days) hospital discharge to home, inpatient rehabilitation or another hospital. At the hospital, within seven days after ICU discharge, all eligible patients were assessed in a face-to-face interview (called “discharge interview” here) for potential NDE using the Greyson NDE scale (Greyson, 1983). This 16-item multiple-choice validated scale assesses core content components of 16 NDE features. For each item, the scores are arranged on an ordinal scale ranging from 0 to 2 (i.e., 0=“not present,”1=“mildly or ambiguously present,” and 2=“definitively present”). Based on their response to the Greyson NDE scale (i.e., cut-off score ≥7/32 for an NDE), the cohort was then divided into two groups: the NDE group and the non-NDE group. In total, 126 participants were included in this prospective study and interviewed 5 (3–7) days after ICU discharge (see Rousseau et al., 2023 for details). Out of this sample, 19 patients (15 %) reported having experienced a NDE as identified by the Greyson NDE scale (i.e., cut-off score of ≥7/32) (NDE group). All the other 107 patients were included in the non-NDE group (i.e., cut-off score of <7/32). See Fig. 1 for enrolment flowchart of the study.

Enrolment flowchart (adapted from Rousseau et al., 2023). The flowchart provides a schematic overview of the entire study. The data reported in this article are derived from the two follow-up interviews: one conducted at 1 month (in yellow) and the other at 1 year (in blue).

At one month following the discharge interview (“1-month interview”), patients from the NDE group (only) were interviewed face-to-face using several closed format questions. Patients were questioned about their feeling of living a life-threatening situation during the ICU stay (binary yes/no answer: “yes, I think I was dying or in a life-threatening situation” or “no, I do not think I was dying or in a life-threatening situation”), about the impression of reality, about whether they think their NDE is a proof of an afterlife, and about the duration of the experience (see the Results section for details about these questions). The French version (D'Argembeau & Van der Linden, 2008) of the Memory Characteristics Questionnaire (MCQ) (Johnson et al., 1988) aiming to assess phenomenological characteristics of the memory, was also administered. This questionnaire encompasses 16 rating scales assessing feeling of re-experiencing, visual details, other sensory details, location, time, coherence, verbal component, emotion while remembering, belief that the event is real, one's own actions, words and thoughts, visual perspective, emotional valence, personal importance, and reactivation frequency (each on a 1–7 point Likert scale). Finally, we asked the patients if they had already experienced a similar subjective experience before their ICU admission.

Patients from both groups were contacted by phone one year after enrolment (“1-year interview”), to question about their feeling of living a life-threatening situation during the ICU stay, and about any changes in beliefs or opinions on death since the ICU discharge (using 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 “much more afraid of death”, 3 “no change” to 5 “no longer afraid of death at all”). The Greyson NDE scale was also administered. Patients from the NDE group only were also questioned about the impression of reality and about the potential impact of the experience on their life, well-being, self-acceptance, relationship with others, opinion on religion and love, mental awareness, and how meaningful it was (see the Results section for details about these questions).

Demographic data, medical history and data related to the ICU stay were prospectively extracted from the medical charts.

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, after approval by the Ethics Committee of the Medicine Faculty of the University of Liège and registration on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04279171). Informed consent was obtained from all the patients.

Statistical analysesNo sample size was calculated since it was an observational study with no previous existing data in such category of patients.

The normality of the quantitative variables was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test (p < 0.05). Qualitative variables were described using counts and percentages. Results were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) or as medians with interquartile range (IQR) (Q1-Q3) for asymmetric distribution. T-tests or non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to determine the statistical differences between the NDE and non-NDE groups for continuous variables. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were performed to assess potential differences in the Greyson NDE score at the discharge interview and one year later in the whole sample of patients and within each group. Results were considered significant at the level of α=5 % (p < 0.05).

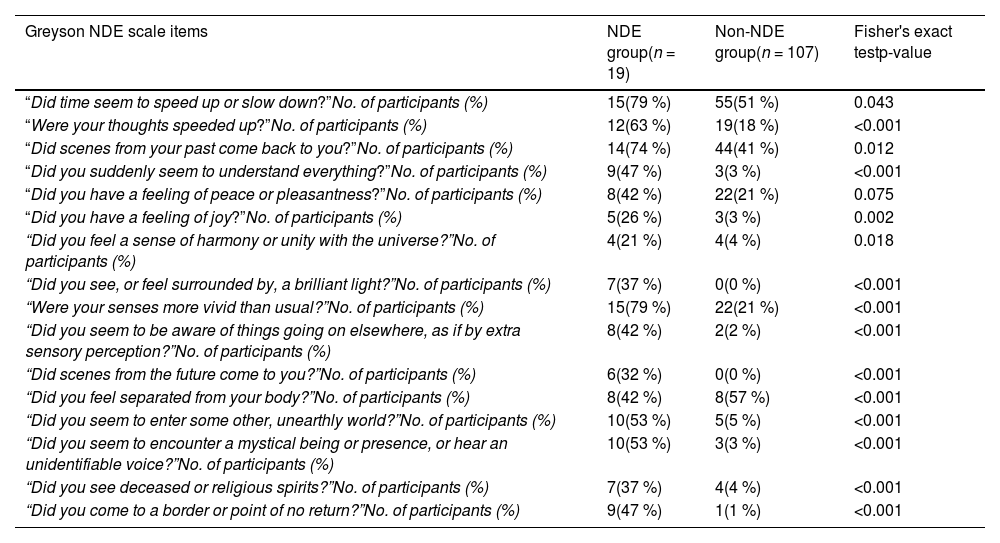

ResultsDischarge interviewSignificantly larger scores for the NDE group as compared to the non-NDE group were found for all items of the Greyson NDE scale, except the one related to the experience of a feeling of peacefulness (p = 0.75) (see Appendix Table 1 for details). Fig. 2 represents the phenomenology of the subjective experiences reported by both the NDE and the non-NDE groups. Note that the two groups did not differ in terms of sociodemographic characteristics and medical history (see Rousseau et al., 2023 for details).

Response frequency distributions in the NDE (n = 19) and non-NDE (n = 107) groups for each of the 16 Greyson NDE scale items (by decreasing order according to responses of the NDE group), administrated at the discharge interview. The presence of the item corresponds to a rating of 1 or 2 of the response scoring. *p < 0.05.

Ten of the 19 patients of the NDE group were followed at 1 month after enrolment (Fig. 1). The responses to each of the closed-format questions are detailed in Table 1. In addition, three out of the four patients who answered they thought the experience was ‘real’ reported that they believe the experience is proof of life after death. Two out of the five patients who think the experience is proof of an afterlife thought they were dying or in a life-threatening situation.

Closed format questions at 1-month follow-up.

| Question | Response possibility | All patients (n = 10) |

|---|---|---|

| During your stay in the intensive care, did you think that you were dying or that you were in a life-threatening situation?No. of patients (%) | YesNo | 4 (40 %)6 (60 %) |

| Do you consider that the experience is ‘real’ (i.e., different from a dream or a hallucination)?No. of patients (%) | YesNo | 4 (40 %)6 (60 %) |

| Do you think the experience is proof of an afterlife?No. of patients (%) | YesNo | 5 (50 %)5 (50 %) |

| According to you, what was the total time duration of your experience?No. of patients (%) | 1 – “One to several seconds” | 1 (10 %) |

| 2 – “One to several minutes” | 6 (60 %) | |

| 3 – “One to several hours” | 2 (20 %) | |

| 4 – “One to several days” | 1 (10 %) |

Patients’ scores on each of the 16 MCQ items were used to characterize the NDE memory: Feeling of re-experiencing (median=2; IQR=1–7), visual details (median=7; IQR=6-7), other sensory details (median=4; IQR=1–5), location (median=7; IQR=6-7), time (median=1; IQR=1–3), coherence (median=5; IQR=4–7), verbal component (median=5; IQR=1–6), feeling emotions (median=7; IQR=2–7), real/imagine (median=7; IQR=7-7), one's own actions (median=7; IQR=6-7), one's own words (median=7; IQR=1–7), one's own thoughts (median=7; IQR=6-7), visual perspective (median=7; IQR=5–7), valence (median=6; IQR=2–7), personal importance (median=7; IQR=3–7), and reactivation frequency (median=6; IQR=3–7).

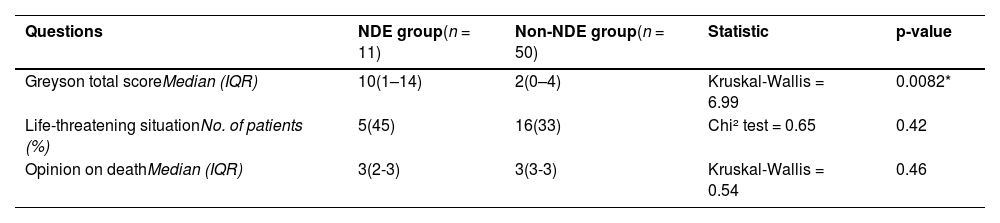

1-year interviewComparison NDE vs non-NDE groupFifty patients (47 %) out of the 107 included patients of the non-NDE group and 11 patients (58 %) out of the 19 included patients of the NDE group were successfully contacted by phone at 1-year after inclusion (see Fig. 1). There were no significant differences observed for both questions regarding the opinion on being in a life-threatening situation during the ICU stay and about any change in opinions on death. The Greyson NDE scale total scores remained, however, significantly different between the two groups when re-administered one year later, as expected (see Table 2). The Greyson total score did not evolve over time (discharge interview versus 1-year interview), either for all our patients (p = 0.46; mean=3.43, SD=3.8 at discharge interview; mean=3.76, SD=4.55 at 1-year interview) and by patient group (NDE group: p = 0.086; non-NDE group: p = 0.84). Fig. 3 presents the details about the responses of the patients from both groups regarding the question asking for any potential change in opinions on death.

Greyson NDE scale total scores and closed format questions at 1 year after inclusion for the two groups.

| Questions | NDE group(n = 11) | Non-NDE group(n = 50) | Statistic | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greyson total scoreMedian (IQR) | 10(1–14) | 2(0–4) | Kruskal-Wallis = 6.99 | 0.0082* |

| Life-threatening situationNo. of patients (%) | 5(45) | 16(33) | Chi² test = 0.65 | 0.42 |

| Opinion on deathMedian (IQR) | 3(2-3) | 3(3-3) | Kruskal-Wallis = 0.54 | 0.46 |

IQR= interquartile range.

Patients’ responses to closed-format questions asked only to the NDE group (n = 8) are presented in Table 3. Note that three patients of this group did not reply to the following questions. Notably, they all reported a positive significant effect of the experience on their self-acceptance and reported an increased sense of importance of love. For those who scored between 1 and 5 on the question “Did the experience have a negative impact on your life?”, a list of potential reasons were provided to the patients: one patient reported that it was due to the difficulty in integrating the experience itself, one patient reported that it was due to the difficulty in integrating the context of the experience, one patient reported that it was due to the difficulty to share the experience with others, two patients reported that it was due to the sense of reality of the experience, one patient reported that it was due to the metaphysical implication of the experience, one patient reported that it was due to the subsequent recurring flashbacks, one patient reported that it was due to the subsequent outstanding/open issues following the experience, two patients reported that it was due to the desire to relive the same experience, and one patient answered that it was not due to any reason suggested below.

Closed format questions at 1 year after inclusion.

| Questions | Response possibility | NDE group (n=8) |

|---|---|---|

| Do you consider that the experience is ‘real’ (i.e., different from a dream or a hallucination)?No. of patients (%) | Yes | 6 (75%) |

| No | 2 (25%) | |

| Did the experience have a positive impact on your life?No. of patients (%) | 0 – “No positive impact” | 3 (37.5%) |

| 1 | 0 (0%) | |

| 2 | 1 (12.5%) | |

| 3 | 1 (12.5%) | |

| 4 | 2 (25%) | |

| 5 – “Very significant positive impact” | 1 (12.5%) | |

| Did the experience have a negative impact on your life?No. of patients (%) | 0 – “No negative impact” | 5 (62.5%) |

| 1 | 0 (0%) | |

| 2 | 2 (25%) | |

| 3 | 0 (0%) | |

| 4 | 1 (12.5%) | |

| 5 – “Very significant negative impact” | 0 (0%) | |

| Did the experience have a significant impact on your lifestyle?No. of patients (%) | 0 – “No impact” | 4 (50%) |

| 1 | 0 (0%) | |

| 2 | 0 (0%) | |

| 3 | 1 (12.5%) | |

| 4 | 1 (12.5%) | |

| 5 – “Very significant impact” | 2 (25%) | |

| Did the experience have a positive effect on your well-being?No. of patients (%) | 0 – “No positive effect” | 3 (37.5%) |

| 1 | 0 (0%) | |

| 2 | 0 (0%) | |

| 3 | 1 (12.5%) | |

| 4 | 4 (50%) | |

| 5 – “Very significant positive effect” | 0 (0%) | |

| Did the experience have a negative effect on your well-being?No. of patients (%) | 0 – “No negative effect” | 7 (87.5%) |

| 1 | 0 (0%) | |

| 2 | 1 (12.5%) | |

| 3 | 0 (0%) | |

| 4 | 0 (0%) | |

| 5 – “Very significant negative effect” | 0 (0%) | |

| Did the experience have a significant effect on your self-acceptance?No. of patients (%) | -2 – “Decreased self-acceptance” | 0 (0%) |

| -1 | 0 (0%) | |

| 0 – “No effect” | 0 (0%) | |

| +1 | 6 (75%) | |

| +2 – “Increased self-acceptance” | 2 (25%) | |

| Did the experience have a significant effect on your relationship with others?No. of patients (%) | 0 – “No effect” | 1 (12.5%) |

| 1 | 0 (0%) | |

| 2 | 2 (25%) | |

| 3 | 0 (0%) | |

| 4 | 2 (25%) | |

| 5 – “I'm more oriented towards others” | 3 (37.5%) | |

| How personally meaningful was the experience?No. of patients (%) | 0 – “No more than routine/everyday experience” | 1 (12.5%) |

| 1 | 2 (25%) | |

| 2 | 0 (0%) | |

| 3 | 1 (12.5%) | |

| 4 | 2 (25%) | |

| 5 – “The single most meaningful experience of my life” | 2 (25%) | |

| Have your beliefs/opinions changed regarding religion?No. of patients (%) | -2 – “Much less religious beliefs” | 0 (0%) |

| -1 | 2 (25%) | |

| 0 – “No change” | 0 (0%) | |

| +1 | 3 (37.5%) | |

| +2 – “Much more religious beliefs” | 3 (37.5%) | |

| Have your beliefs/opinions changed regarding love?No. of patients (%) | -2 – “Decreased sense of importance of love” | 0 (0%) |

| -1 | 0 (0%) | |

| 0 – “No change” | 0 (0%) | |

| +1 | 4 (50%) | |

| +2 – “Increased sense of importance of love” | 4 (50%) | |

| Did the experience allow you to expand your mental awareness?No. of patients (%) | 0 – “No at all” | 3 (37.5%) |

| 1 | 0 (0%) | |

| 2 | 0 (0%) | |

| 3 | 1 (12.5%) | |

| 4 | 3 (37.5%) | |

| 5 – “Fully more expanded mental awareness” | 1 (12.5%) |

This 1-year longitudinal study is the first prospective study investigating the phenomenological memory characteristics and impact of the NDEs recalled by patients discharged from the ICU after a prolonged stay, no matter what critical illness they survived. Regarding the characterization of the prototypical NDE features reported at the discharge interview, the most frequently reported ones by patients of our NDE group were altered time perception, heightened senses (i.e., senses more vivid than usual), life review (i.e., the emergence of vivid memories of past experiences or scenes), speeded thoughts and encountering a mystical being or presence. It can be observed that some of the most commonly reported features in other studies such as the out-of-body experience and an intense feeling of peacefulness (Charland-Verville et al., 2014; Greyson, 2003; Lai et al., 2007; Schwaninger et al., 2002), are not necessarily the most frequent ones here. Interestingly, the experience of life review was reported as the third most frequent features by our NDE patients, whereas this is generally reported as one of the least common features reported by NDE experiencers in the empirical literature (Charland-Verville et al., 2014; Greyson, 2003).

Importantly, we observed that 89 patients (71 % of the patient sample included in this study) scored between 1 and 6 on the Greyson NDE scale. This suggests that a large proportion of our sample had some subjective experiences (including features that are prototypical to NDE) but were not considered as sufficiently rich to be apparent to what is considered —so far— as a NDE (because not reaching the validated cut-off score of 7/32 on the Greyson NDE scale; Greyson, 1983). The three most frequently reported features by the patients from the non-NDE group were altered time perception, life review, and a feeling of peacefulness. It is worth mentioning that all of these experiences —regardless of whether or not they were classified as an NDE by the Greyson NDE scale— are important, especially from a clinical perspective notably since some of these features may have extraordinary aspects (e.g., out-of-body experience) that could present challenges in their integration into daily life. More generally, the potential consequences of having experienced such features remain unknown, particularly in terms of post-traumatic stress disorders or anxiety occurrence.

One month after the discharge interview, NDE experiencers reported a relatively high amount of qualitative phenomenological memory characteristics. Although the present study does not allow for a comparison of the ratings associated to the NDE memory with other types of memory, one can nevertheless observe that the ratings are particularly high, as compared to what can be typically found in the literature for non-NDE event memories (see for example the ratings reported in D'Argembeau & Van der Linden, 2008; Thonnard et al., 2013). In other words, the NDE memory is associated with a consequent number of features (be they sensory, contextual, semantic and/or emotional) that characterize the phenomenological experience associated with remembering. The higher scores were associated with items assessing visual details, location, feeling emotions, belief that the event is real, visual perspective, personal importance, and one's own actions, words and thoughts. Overall, this finding is consistent with the existing literature demonstrating that NDEs are characterized by a particularly rich and clear memory (Martial et al., 2017; Moore & Greyson, 2017). Although it may seem counterintuitive to obtain such a rich memory after these critical circumstances, it has been hypothesized that the encoding and consolidation of the NDE memory could be explained by the release of specific neurotransmitters such as epinephrine (Cahill & Alkire, 2003; Martial et al., 2020b).

At a group level, the sample of NDE experiencers interviewed at 1 month after the discharge assessment reported mixed responses regarding their impression of having lived a life-threatening situation, their impression of reality, whether they think the experience is a proof of an afterlife, and their impression of duration of the NDE. Of note, four out of the five who answered that they consider that the experience was ‘real’ (defined here as different from a dream or a hallucination) reported that they think the experience is proof of an afterlife. Although very speculative, we may hypothesize that having the impression that the experience was ‘real’ might lead the individual to somehow mystify the NDE and consequently the belief of a supposed afterlife. In addition, only two of the five people who thought that the NDE is proof of an afterlife considered to be in a life-threatening situation or dying. While this matter has been discussed previously (Blackmore, 1996; Owens et al., 1990), it does not seem that these two beliefs are necessarily associated. However, we do not know the beliefs of the patients prior to their admission to ICU. Further research with larger samples is needed.

One year later, the perception of a life-threatening situation during ICU stay does not seem to be influenced by a previous NDE. In addition, the Greyson total score did not change one year later, whether analyzed for the whole sample of patients or for each patient group. This is consistent with the only study addressing the question of the long-term evolution of NDE memory and suggesting that accounts of NDEs were not modified even over a period of two decades (Greyson, 2007).

Most of the respondents reported to not have modified their opinion on death during the year following their admission in ICU. More specifically, only two (18 %) patients from the NDE group (versus 12 [24 %] patients in the non-NDE group) reported being less afraid of death. This finding is inconsistent with prior research showing a decrease in the fear of death in most of the people having experienced a NDE (Greyson, 2006; Noyes et al., 2009; van Lommel et al., 2001). This effect may be related to the way they interpret their experience or their prolonged stay in ICU, as well as the associated “sense of reality”. Moreover, one year after the ICU stay, all respondents of the NDE group did report a positive significant effect of the experience on their self-acceptance and reported an increased sense of importance of love. For the other questions related to the impact, the results are rather mixed, such as the question asking to what extent the experience was personally meaningful for them. Further studies including a larger sample of NDE experiencers are needed to characterize the impact of these unique experiences. This is especially crucial knowing that NDEs are generally reported as transforming, in particular at a personal and spiritual level, and often lead to changes in values and life insights (e.g., a new sense of life purpose, increased love for others) (Bianco et al., 2019; Groth-Marnat and Summers, 1998; Pehlivanova et al., 2023; Sweeney et al., 2022). It is nevertheless important to note that changes are not always positive but can also be very negative for some experiencers (Cassol et al., 2019). From a theoretical viewpoint, it seems crucial to differentiate NDEs from other episodes such as delirium (see Danielis et al., 2024 for a recent systematic review on delusional memories from ICU), in order to best help patients integrate their experiences into their life after their ICU stay. Indeed, as evidenced by the present results, some individuals who have experienced a NDE seem to report subsequent difficulties, notably in integrating the experience itself, its associated sense of reality, or the subsequent recurring flashbacks. To better determine the impact of NDE on psychological outcomes and beliefs, we emphasize the clinical importance of conducting systematic interviews with all ICU patients to explore any potential memory upon awakening. If a NDE or any other unusual subjective experience is detected, it may be advisable to recommend appropriate follow-up.

Several limitations warrant acknowledgment. Firstly, the monocentric nature of the study and the limited number of patients who experienced NDEs must be acknowledged. Secondly, we used a scale with closed questions to identify NDEs. Such standardized quantitative scales lead to a limited vision/understanding of the NDEs. However, this was the most rigorous way to identify, quantify and compare the different NDEs. Thirdly, our study assessed NDE memories using the MCQ relatively early (i.e., one month later). This was our precise intention to assess the NDE memory at an early stage, in case of potential subsequent memory impairments. Another related limitation is the lack of cognitive and memory impairment evaluation at the time of the interviews. Finally, caution should be exercised in drawing general conclusions from the present results, given the potential bias stemming from the significant loss of follow-up over the 1-year follow-up period.

ConclusionsIn this cohort study including all types of ICU survivors, the NDE memory did not change during the year following the first interview. The NDE memory was associated with a consequent number of qualitative phenomenological memory characteristics (e.g., visual details, emotions). Most of the patients who experienced NDE did not modify their opinion on death one year later, with a moderate proportion of patients being less afraid of death. The NDE group reported subsequent difficulties to integrate the NDE into their life. Because the impact of NDE on psychological outcomes of ICU survivors is currently unknown, it is clinically significant to conduct systematic interviews with all ICU survivors to explore any possible memory and, if so, to suggest appropriate follow-up.

FundingThe work was supported by the University and University Hospital of Liège, the Belgian National Funds for Scientific Research (FRS-FNRS), the BIAL Foundation, the European Union's Horizon 2020 Framework Programme for Research and Innovation under the Specific Grant Agreement No. 945539 (Human Brain Project SGA3), the ERA-Net FLAG-ERA JTC2021 project ModelDXConsciousness (Human Brain Project Partnering Project), the fund Generet, the King Baudouin Foundation, and the Fondation Leon Fredericq. O.G. is research associate at the F.R.S-FNRS.

CRediT authorship contribution statementCharlotte Martial: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Resources, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Visualization, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Pauline Fritz: Data curation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Helena Cassol: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Resources, Data curation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Olivia Gosseries: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Bernard Lambermont: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Benoit Misset: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Anne-Françoise Rousseau: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Resources, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

We want to thank the patients for their availability, as well as Steven Laureys, Nadia Dardenne, Laurence Dams, Quantin Massart and Laila Choquer for their support.

Phenomenology reported by both the NDE and non-NDE group according to the Greyson NDE scale. The presence of the item corresponds to a rating of 1 or 2 of the response scoring.

| Greyson NDE scale items | NDE group(n = 19) | Non-NDE group(n = 107) | Fisher's exact testp-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Did time seem to speed up or slow down?”No. of participants (%) | 15(79 %) | 55(51 %) | 0.043 |

| “Were your thoughts speeded up?”No. of participants (%) | 12(63 %) | 19(18 %) | <0.001 |

| “Did scenes from your past come back to you?”No. of participants (%) | 14(74 %) | 44(41 %) | 0.012 |

| “Did you suddenly seem to understand everything?”No. of participants (%) | 9(47 %) | 3(3 %) | <0.001 |

| “Did you have a feeling of peace or pleasantness?”No. of participants (%) | 8(42 %) | 22(21 %) | 0.075 |

| “Did you have a feeling of joy?”No. of participants (%) | 5(26 %) | 3(3 %) | 0.002 |

| “Did you feel a sense of harmony or unity with the universe?”No. of participants (%) | 4(21 %) | 4(4 %) | 0.018 |

| “Did you see, or feel surrounded by, a brilliant light?”No. of participants (%) | 7(37 %) | 0(0 %) | <0.001 |

| “Were your senses more vivid than usual?”No. of participants (%) | 15(79 %) | 22(21 %) | <0.001 |

| “Did you seem to be aware of things going on elsewhere, as if by extra sensory perception?”No. of participants (%) | 8(42 %) | 2(2 %) | <0.001 |

| “Did scenes from the future come to you?”No. of participants (%) | 6(32 %) | 0(0 %) | <0.001 |

| “Did you feel separated from your body?”No. of participants (%) | 8(42 %) | 8(57 %) | <0.001 |

| “Did you seem to enter some other, unearthly world?”No. of participants (%) | 10(53 %) | 5(5 %) | <0.001 |

| “Did you seem to encounter a mystical being or presence, or hear an unidentifiable voice?”No. of participants (%) | 10(53 %) | 3(3 %) | <0.001 |

| “Did you see deceased or religious spirits?”No. of participants (%) | 7(37 %) | 4(4 %) | <0.001 |

| “Did you come to a border or point of no return?”No. of participants (%) | 9(47 %) | 1(1 %) | <0.001 |

NDE =near-death experience; SD=standard deviation.+++++++++++++++++