The transition to parenthood encompasses several psychological and relational changes that might contribute to couples’ high levels of stress postpartum. Although common across the postpartum, couples’ sexual changes are frequently overlooked.

MethodWe surveyed 255 mixed-sex new parent couples to examine the associations between sexual well-being—sexual satisfaction, desire, and postpartum sexual concerns—and perceived stress postpartum. Couples completed self-report questionnaires assessing perceived stress and sexual well-being.

ResultsFor both mothers and fathers, greater sexual satisfaction was associated with their partners’ lower perceived stress and, for fathers, this was also associated with their own lower perceived stress. For mothers, greater partner-focused sexual desire was associated with their own lower perceived stress whereas, for fathers, greater partner-focused sexual desire was associated with their partners’ higher perceived stress. In addition, greater solitary sexual desire and postpartum sexual concerns were associated with both parents’ own higher perceived stress.

ConclusionsThis study highlights the association between sexual well-being and couples’ postpartum stress, suggesting that more positive sexual experiences are linked to lower perceptions of stress across this vulnerable period. Couples’ sexual well-being may be an important target for interventions aimed at helping postpartum couples cope with stress.

La transición a la paternidad implica cambios psicológicos y relacionales que pueden contribuir a niveles de estrés postparto de las parejas. Aunque son comunes en el periodo de posparto, los cambios a nivel sexual de las parejas no se tienen en cuenta habitualmente.

MétodoSe examinó la asociación entre bienestar sexual—satisfacción sexual, deseo y preocupaciones sexuales postparto—y estrés percibido postparto en una muestra de 255 parejas de padres recientes.

ResultadosEn padres y madres, mayor satisfacción sexual se asoció con un menor estrés percibido de sus parejas y, para los padres, también se asoció con su propio menor estrés percibido. Para las madres, un mayor deseo sexual centrado en la pareja se asoció con su menor estrés percibido; para los padres, un mayor deseo sexual centrado en la pareja se asoció con un mayor estrés percibido de las madres. Mayor deseo sexual solitario y más preocupaciones sexuales posparto se asociaron con mayor estrés percibido de ambos padres.

ConclusionesExperiencias sexuales más positivas se asociaron con menor experiencia de estrés en el posparto, por lo que el bienestar sexual puede ser un componente importante para las intervenciones destinadas a ayudar a las parejas a enfrentar el estrés posparto.

The transition to parenthood is a demanding and stressful life transition that may place couples at risk for psychological and relational problems (Da Costa et al., 2019; Doss & Rhoades, 2017; Vismara et al., 2016). Novel challenges arise during this transition (e.g., breastfeeding, fatigue/sleep deprivation, parenting decisions, couple members’ changing roles and responsibilities) which may create an intense threat or demand on the individual and/or couple (Doss & Rhoades, 2017). Depending on individual, relational, or contextual factors, such challenges might be perceived as exceeding one's coping resources, thus affecting individual or dyadic functioning in a process designated as “stress” (Ben-Zur, 2019; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Increased stress postpartum is associated with mothers’ decreased sensitivity to and engagement with their infants’ cues (Clowtis, Kang, Padhye, Rozmus, & Barratt, 2016; Shin, Park, Ryu, & Seomung, 2008) and to mothers’ and fathers’ postpartum depression (Da Costa et al., 2019; Vismara et al., 2016). Stress has also been found to hinder couples’ relationship functioning and longevity (Randall & Bodenmann, 2017).

Sexual well-being during the transition to parenthoodThe postpartum period also impacts couples’ sexual well-being, but changes to the sexual relationship during the transition to parenthood are a commonly overlooked challenge. Sexual well-being is defined as a global state of physical, mental, and social well-being regarding sexuality (World Health Organization, 2002). After childbirth, dimensions of couples’ sexual well-being that are commonly affected include sexual satisfaction, sexual desire, and event-specific (i.e., postpartum) sexual concerns, such as worries about the impact of physical recovery from childbirth on sexuality or when to safely resume intercourse (Ahlborg, Dahlof, & Hallberg, 2005; McBride & Kwee, 2017; Schlagintweit, Bailey, & Rosen, 2016).

New parents’ experience reduced sexual satisfaction relative to pre-pregnancy levels. Specifically, one third to half of first-time parents report feeling dissatisfied with their sex lives at 6 to 8 months postpartum (Ahlborg et al., 2005; Yildiz, 2015). New mothers also commonly report reduced sexual desire in the first year postpartum in comparison to pre-pregnancy (McBride & Kwee, 2017). Some studies show no changes in new fathers’ sexual desire over the course of this transition (Radoš, Vraneš, &Šunjić, 2015), while others indicate a decline in fathers’ sexual desire (Condon, Boyce, & Corkindale, 2004). Moreover, many new parents report novel sexual concerns that are specific to the postpartum. Prior cross-sectional studies indicate that almost 90% of new parents endorsed at least 10 postpartum sexual concerns during the first year postpartum and that each concern was associated with a moderate degree of distress in mothers and fathers alike (Pastore, Owens, & Raymond, 2007; Schlagintweit et al., 2016). Still, not all couples experience negative sexual changes, with 30% to 50% of couples reporting sustained or even increased sexual satisfaction across the transition relative to pre-pregnancy (e.g., Ahlborg, Rudeblad, Linnér, & Linton, 2008), denoting the marked variability of couples’ postpartum sexual experiences.

Sexual well-being and stressCumulative research efforts have identified several positive determinants of overall well-being (e.g., Sapranaviciute-Zabazlajeva et al., 2018; Schönfeld, Brailovskaia, & Margraf, 2017; Wersebe, Lieb, Meyer, Hofer, & Gloster, 2017). Sexual well-being in particular has been found to have wide-reaching benefits including for overall well-being and quality of life, marital quality and stability, and mental health (e.g., Diamond & Huebner, 2012; Sánchez-Fuentes, Santos-Iglesias, & Sierra, 2014; Stephenson & Meston, 2015). There is also some evidence for an association between sexual well-being and the regulation of stress (Ein-Dor & Hirschberger, 2012).

In the general context of couples’ relationships, some studies indicate that self-reported stress correlates positively with sexual difficulties and negatively with sexual satisfaction and sexual activity (Bodenmann, Ledermann, & Bradbury, 2007), whereas others indicate a positive relation between stress and levels of sexual activity (Burri & Carvalheira, 2019; Morokoff & Gillilland, 1993). This latter finding has led some authors to propose that positive sexual relationships may be especially important to reduce tension and deal with stress.

Theoretical models suggest that greater sexual well-being might be a protective factor for lower stress (theory of emotional capital; Feeney & Lemay, 2012) and that poorer sexual well-being may be a risk factor for heightened stress (transactional model of stress; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). The theory of emotional capital (Feeney & Lemay, 2012) suggests that partners who accumulate greater “emotional capital”—a series of positive, emotionally shared experiences, such as positive sexual interactions—are less reactive to relationship stressors and threats than couples with lower emotional capital (Walsh, Neff, & Gleason, 2016). Thus, couples with greater sexual well-being in the transition to parenthood might be more protected against the experience of stress.

Alternatively, the transactional model posits that stress results when the demands of a situation are perceived to exceed an individual's resources to cope with those demands (Ben-Zur, 2019; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). The resources needed to maintain a satisfying postpartum sex life may be perceived as especially taxing given novel sexual (e.g., desire discrepancy, pain) and general challenges (e.g., fatigue, parenting decisions) of this life transition, resulting in heightened postpartum stress. Taken together, both theories suggest that sexual well-being may have implications for new parents’ experience of stress.

Sexual well-being, stress, and the transition to parenthoodDespite evidence that the transition to parenthood is a time of high variability in stress and sexual well-being, studies that assess the relationship between these aspects are scarce. A longitudinal study found that new mother's greater parenting stress at 6 months postpartum predicted both mothers’ and fathers’ lower sexual satisfaction at 12 months postpartum (Leavitt, McDaniel, Mass, & Feinberg, 2017). In one cross-sectional study, mothers’ postpartum stress and sexual desire were not associated (Hipp, Low, & van Anders, 2012) but, in partners of women who gave birth, postpartum stress was linked to their own low sexual desire (Anders, Hipp, & Low, 2013).

These somewhat mixed findings might be attributable to several important limitations of the prior research. First, these studies have not considered various dimensions of couples’ sexual well-being, but rather typically assess only one dimension of sexual well-being in isolation (e.g., Hipp et al., 2012; Leavitt et al., 2017; van Anders, Hipp, & Low, 2013). Therefore, the relative influence of sexual factors has not been examined, and the potential differential effects of partners’ sexual well-being dimensions, such as sexual desire (dyadic, i.e., interest in behaving sexually with a partner, versus solitary, i.e., interest in behaving sexually by oneself; Moyano, Vallejo-Medina, & Sierra, 2017) or postpartum sexual concerns are still largely unknown. Also, prior studies tend to favor only one partners’ perspective (e.g., Hipp et al., 2012; van Anders et al., 2013). Few studies have taken couple interdependence into account to examine how one parent's sexual well-being is associated with the other parent's experience of stress, despite initial evidence of cross-partner effects (e.g., Leavitt et al., 2017). Our study aims to address these prior limitations.

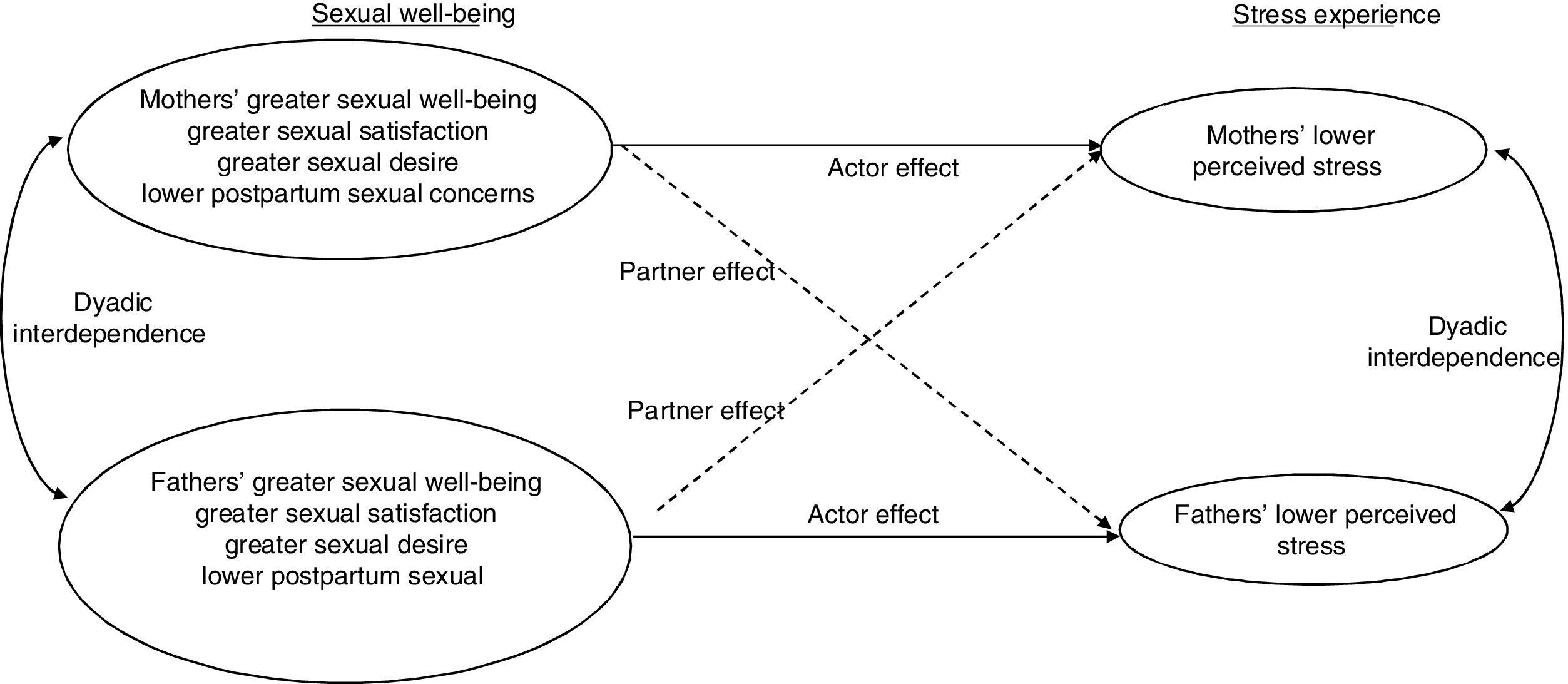

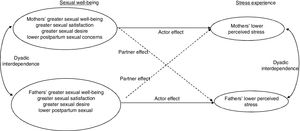

Current studyThe purpose of this study was to examine whether important indicators of postpartum sexual well-being (sexual satisfaction, sexual desire, and sexual concerns specific to postpartum) were associated with perceived stress in a sample of first-time parent couples. We hypothesized that an individual's greater sexual well-being would be associated with both couple members’ lower postpartum stress (Figure 1). To rule out alternative hypotheses, we also examined whether our observed effects could be accounted for by other variables present during the postpartum period and that past research has linked to sexual changes or increased stress across the transition (child age, breastfeeding, maternal fatigue, and pain intensity during intercourse; e.g., McBride & Kwee, 2017) or that are interdependent with couples’ sexual well-being (relationship satisfaction and duration; McNulty, Wenner, & Fisher, 2016; Sánchez-Fuentes et al., 2014). Therefore, we also tested our hypotheses when controlling for these relevant covariates. As postpartum sexual changes are common, findings from this study will contribute to an improved understanding of their particular associations with couples’ stress. This information may ultimately prove relevant for clinicians helping new parents cope with stress.

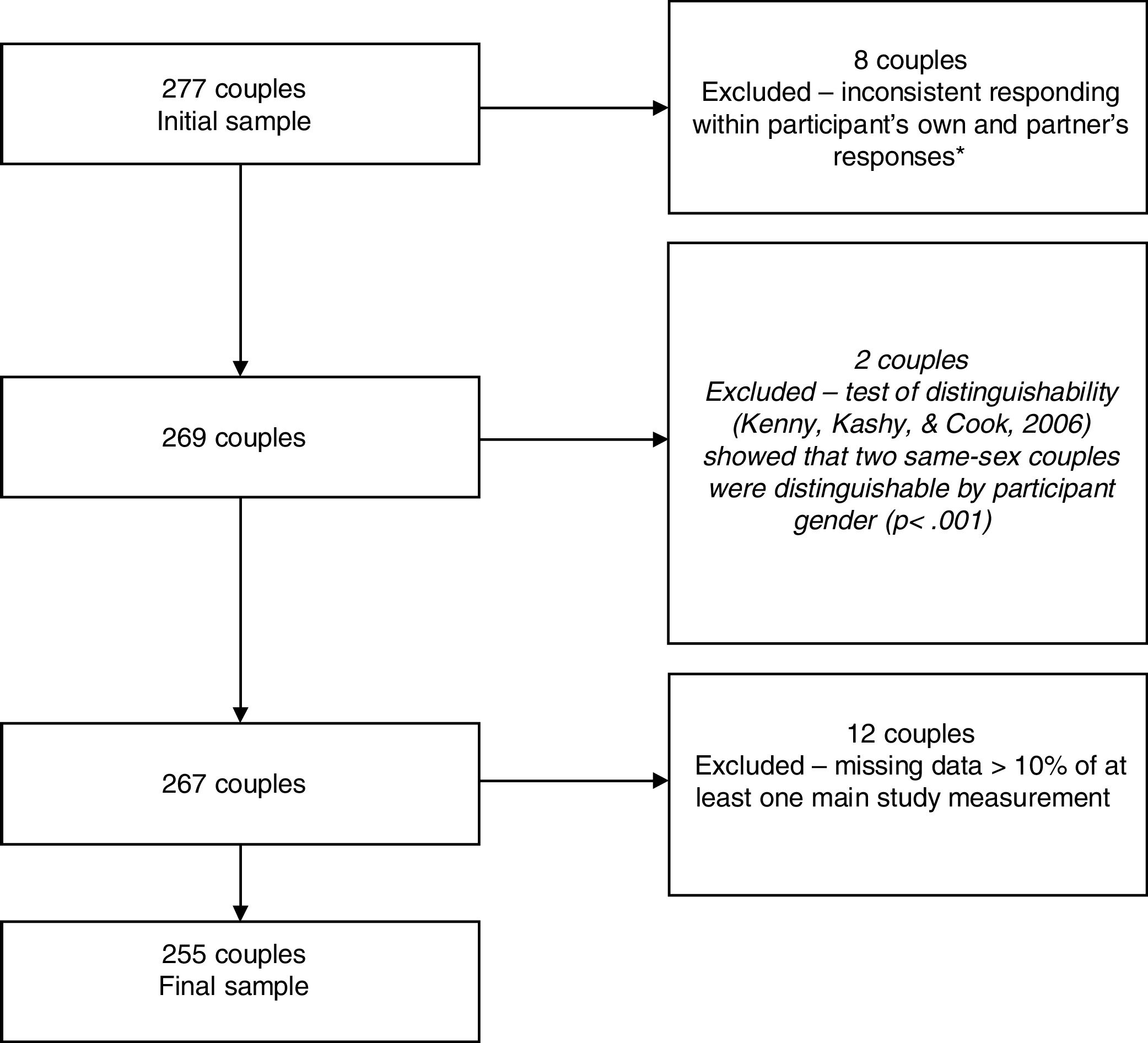

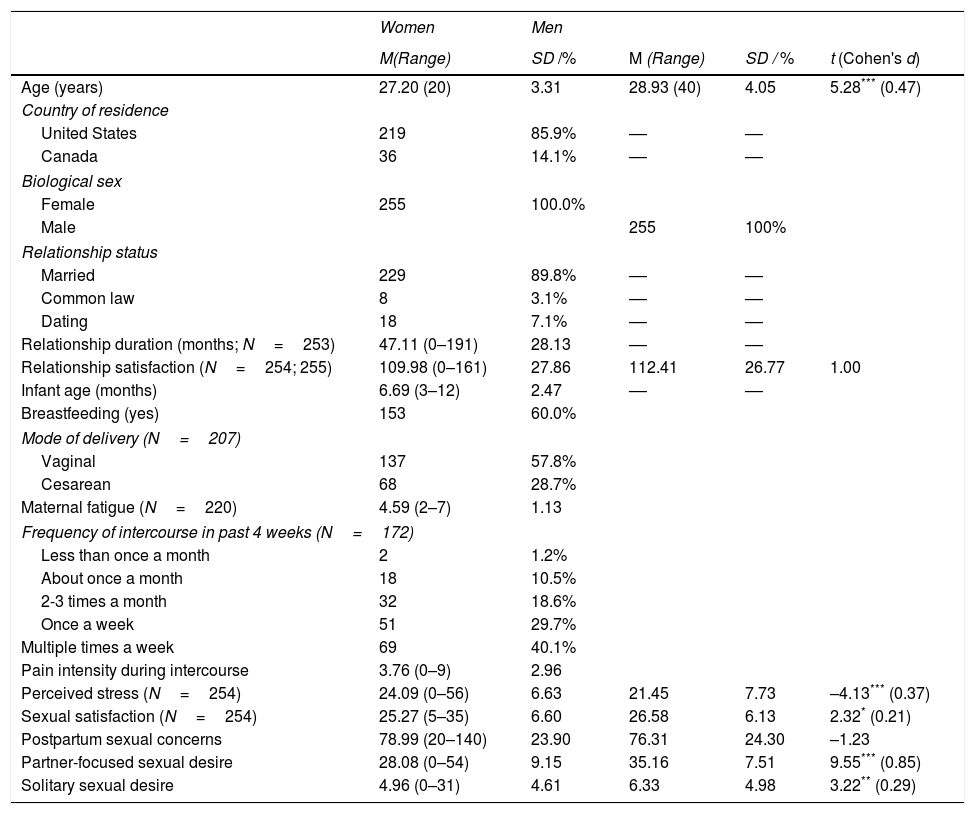

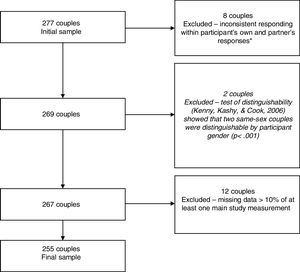

MethodParticipantsThis study included 255 mixed-sex couples. All couples were first-time parents to a singleton child aged three to 12 months at the time of participation, who was born healthy and at term (37 to 42 weeks gestation). Figure 2 depicts information on participant's inclusion flow. Socio-demographic and psychosocial characteristics of study participants are presented in Table 1.

Flow diagram of participants’ inclusion. *To confirm eligibility, several sociodemographic items in the survey overlapped with the eligibility criteria and were compared with participants’ own (and their partners’) responses. This process led to the exclusion of 8 couples due to either inconsistent responding within a participant (i.e., responses on the sociodemographic items that violated the selection criteria; n=4) or inconsistent responding between partners (e.g., woman and partner reported different ages of the child; n=4).

Descriptive Characteristics of the sample (N=255 unless otherwise stated).

| Women | Men | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M(Range) | SD /% | M (Range) | SD / % | t (Cohen's d) | |

| Age (years) | 27.20 (20) | 3.31 | 28.93 (40) | 4.05 | 5.28*** (0.47) |

| Country of residence | |||||

| United States | 219 | 85.9% | –– | –– | |

| Canada | 36 | 14.1% | –– | –– | |

| Biological sex | |||||

| Female | 255 | 100.0% | |||

| Male | 255 | 100% | |||

| Relationship status | |||||

| Married | 229 | 89.8% | –– | –– | |

| Common law | 8 | 3.1% | –– | –– | |

| Dating | 18 | 7.1% | –– | –– | |

| Relationship duration (months; N=253) | 47.11 (0–191) | 28.13 | –– | –– | |

| Relationship satisfaction (N=254; 255) | 109.98 (0–161) | 27.86 | 112.41 | 26.77 | 1.00 |

| Infant age (months) | 6.69 (3–12) | 2.47 | –– | –– | |

| Breastfeeding (yes) | 153 | 60.0% | |||

| Mode of delivery (N=207) | |||||

| Vaginal | 137 | 57.8% | |||

| Cesarean | 68 | 28.7% | |||

| Maternal fatigue (N=220) | 4.59 (2–7) | 1.13 | |||

| Frequency of intercourse in past 4 weeks (N=172) | |||||

| Less than once a month | 2 | 1.2% | |||

| About once a month | 18 | 10.5% | |||

| 2-3 times a month | 32 | 18.6% | |||

| Once a week | 51 | 29.7% | |||

| Multiple times a week | 69 | 40.1% | |||

| Pain intensity during intercourse | 3.76 (0–9) | 2.96 | |||

| Perceived stress (N=254) | 24.09 (0–56) | 6.63 | 21.45 | 7.73 | –4.13*** (0.37) |

| Sexual satisfaction (N=254) | 25.27 (5–35) | 6.60 | 26.58 | 6.13 | 2.32* (0.21) |

| Postpartum sexual concerns | 78.99 (20–140) | 23.90 | 76.31 | 24.30 | –1.23 |

| Partner-focused sexual desire | 28.08 (0–54) | 9.15 | 35.16 | 7.51 | 9.55*** (0.85) |

| Solitary sexual desire | 4.96 (0–31) | 4.61 | 6.33 | 4.98 | 3.22** (0.29) |

Note.

Background Questionnaire. Each participant self-reported their age, country of residence, biological sex, relationship status and duration. Mothers also reported on their baby's age at the time of participation, breastfeeding status, mode of delivery, frequency of intercourse in the past four weeks, pain intensity during intercourse, and average level of energy on a typical postpartum day.

Couples Satisfaction Index (CSI). The well-validated 32-item CSI (Funk & Rogge, 2007) was used to assess relationship satisfaction (e.g., “Please indicate the degree of happiness, all things considered, of your relationship”). Most items are scored on a 6-point rating scale except one global item that is scored on a 7-point scale. Higher scores indicate greater satisfaction (Cronbach's α of .97 for mothers and fathers in the present sample).

Global Measure of Sexual Satisfaction (GMSEX). The GMSEX is a valid and reliable measure of sexual satisfaction in relationships (Lawrance & Byers, 1995). GMSEX comprises five 7-point bipolar scales (e.g., unpleasant–pleasant), with higher scores indicating greater sexual satisfaction. Reliability in the current study was high (Cronbach's αmothers=.91; Cronbach's αfathers=.90).

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS). The PSS is a widely used, valid, and reliable self-report measure of global stress (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983). Current level of perceived stress is assessed using 14 items (e.g., “In the last month, how often have you found that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do?”). Responses are assessed in a 5-point rating scale (from 0=never to 4=very often). Scores range from 0 to 56. Higher scores indicate greater perceived stress. The PSS demonstrated acceptable to good reliability in the present study (Cronbach's αmothers=.75; Cronbach's αfathers=.82).

Postpartum Sexual Concerns Questionnaire–Revised (PSCQ–R). This 20-item self-report questionnaire was used to assess postpartum sexual concerns (Schlagintweit et al., 2016). Participants rated each sexual issue on a 7-point scale (e.g., “Are you concerned about your frequency of intercourse after childbirth?” from 1=not at all concerned to 7=extremely concerned). The global score corresponds to the level of distress associated with postpartum sexual concerns, with higher total scores indicating greater distress. In this study, the scale presented high reliability scores (Cronbach's αmothers=.92; Cronbach's αfathers=.93).

Sexual Desire Inventory–2 (SDI-2). This 14-item questionnaire assesses interest in sexual activity, including one's thoughts on approaching or being responsive to sexual stimuli, in a Likert-type response format (Spector, Carey, & Steinberg, 1996). Higher total scores indicate greater sexual desire. The SDI-2 comprises three subscales: partner-focused dyadic sexual desire, dyadic sexual desire for an attractive other person (DSD-A), and solitary sexual desire (SDD; Moyano et al., 2017). In the current study, only the DSD-P (e.g., “How strong is your desire to engage in sexual activity with a partner?”) and SDD (e.g., “How strong is your desire to engage in sexual behavior by yourself?”) were used. Previous studies revealed high internal consistency and concurrent evidence of validity (Moyano et al., 2017). In the current sample, the subscales demonstrated acceptable to high reliability (DSD-P: Cronbach's αmothers=.83, Cronbach's αfathers=.76; SSD: Cronbach's αmothers=.92, Cronbach's αfathers=.82).

ProcedureThis cross-sectional descriptive study (Montero & León, 2007) received ethical approval from the research ethics board of the last author's institution. Prior studies using this sample and examining predictors of new parents’ sexual well-being (viz., sexual satisfaction, sexual desire, postpartum sexual concerns) have been published (Muise, Kim, Impett, & Rosen, 2017; Rosen, Bailey, & Muise, 2017; Rosen, Mooney, & Muise, 2016; Schlagintweit et al., 2016), but none examining new parents’ perceived stress. North American participants were recruited from September 2014 to May 2015 using online sources as part of a larger, cross-sectional online study on sexuality and relationships during the transition to parenthood. After providing informed consent and prior to beginning the survey, participants completed a screening questionnaire to assess eligibility. Upon completion of the survey, participants provided their partner's e-mail address. The partner was then e-mailed a questionnaire link generated by the survey software comprising a unique couple identifier that allowed data to be linked once both members completed the survey. Both members of each couple were required to complete the survey within four weeks of each other. After completing the survey, individuals received a list of online resources related to sexuality and relationships during the transition to parenthood and were compensated with a $15 gift card.

Data analysisMissing data representing 10% or less of a single measure was replaced by the mean of the scale for that particular person (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). The actor-partner interdependence model (APIM) was estimated using multilevel modelling, where partners were nested within couples (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). Dyads were distinguishable by gender [χ2(10)=65.63, p <.001]. A two-level model with fixed effects and separate intercepts for mothers and fathers was used to examine the associations between mother's and father's sexual well-being and their own (i.e., actor effects) and their partner's (i.e., partner effects) perceived stress. This model included all predictors simultaneously to assess each predictor's association with postpartum stress while controlling for the other predictors. Finally, additional analyses were conducted to control for potential confounding effects of variables related to postpartum stress (e.g., relationship satisfaction). All predictor variables were grand-mean centered before conducting the analyses.

ResultsPreliminary analysesDescriptive statistics for new mothers’ and fathers’ perceived stress and all predictor variables are presented in Table 1. Student t tests indicated that fathers reported higher sexual satisfaction, partner-focused sexual desire, and solitary sexual desire than mothers, but postpartum stress was higher for mothers than for fathers. No significant differences were found between partners on postpartum sexual concerns.

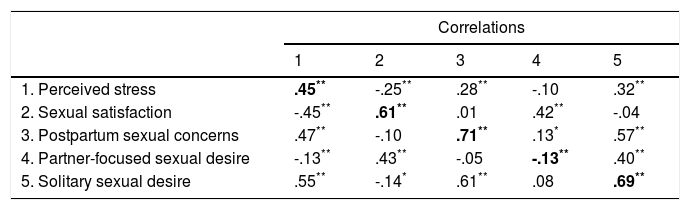

Correlations among study variables are presented in Table 2. Partners’ scores were significantly correlated for all variables, ps <.01. A moderate correlation between partners’ stress was found, suggesting within-dyads interdependence (Kenny et al., 2006). All within-dyads scores were positively correlated at moderate to high levels, except for DSD-P scores, which were negatively correlated at low levels. Between-partner correlations indicated that mother's perceived stress significantly correlated with all of their own sexual well-being domains except DSD-P; fathers’ perceived stress significantly correlated with all of their own sexual well-being domains.

Correlations between perceived stress and the predictor variables.

| Correlations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 1. Perceived stress | .45** | -.25** | .28** | -.10 | .32** |

| 2. Sexual satisfaction | -.45** | .61** | .01 | .42** | -.04 |

| 3. Postpartum sexual concerns | .47** | -.10 | .71** | .13* | .57** |

| 4. Partner-focused sexual desire | -.13** | .43** | -.05 | -.13** | .40** |

| 5. Solitary sexual desire | .55** | -.14* | .61** | .08 | .69** |

Note. Values on the diagonal (in bold) represent within-dyads correlations, values above the diagonal represent within-women correlations, and values below the diagonal represent within-men correlations.

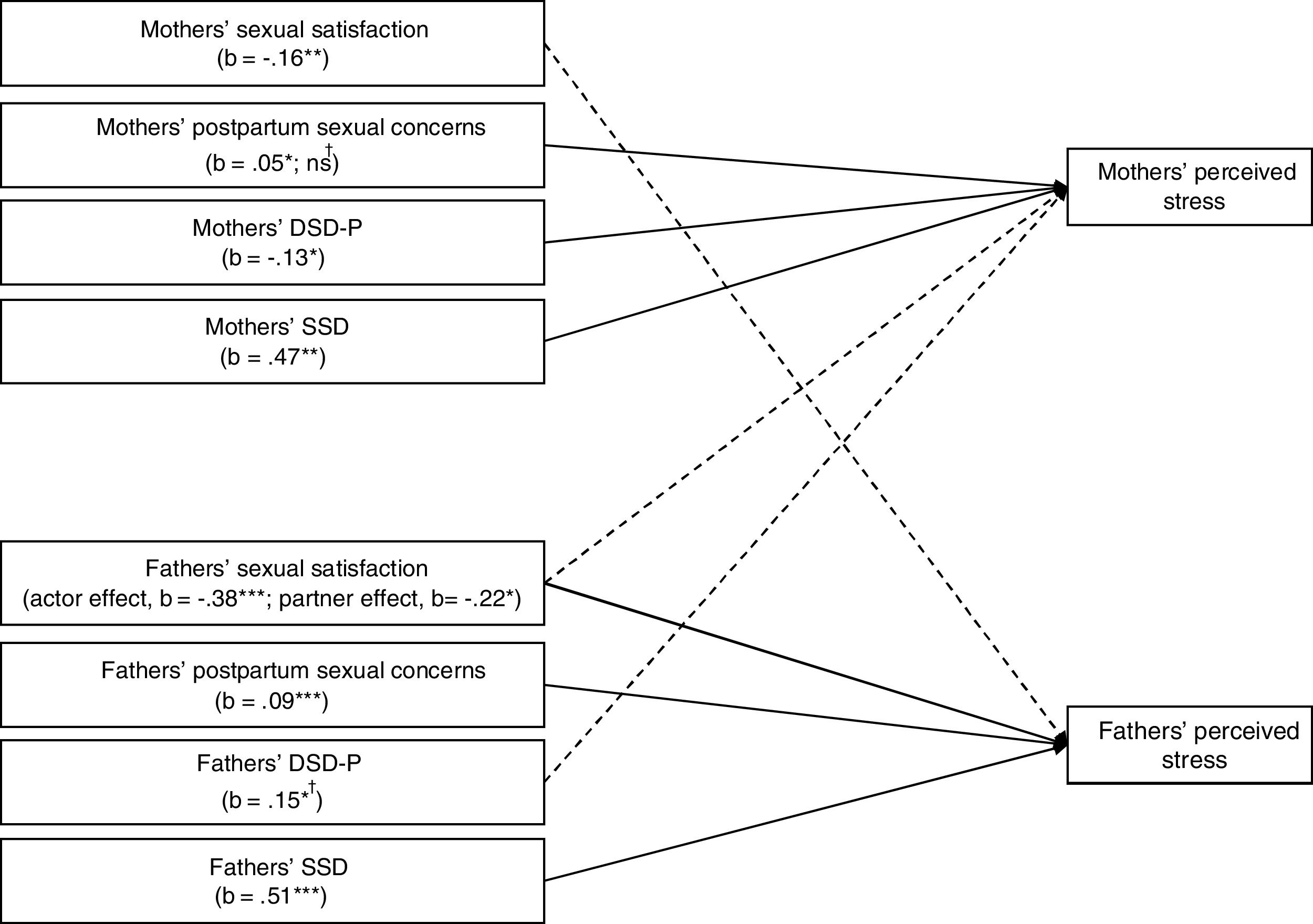

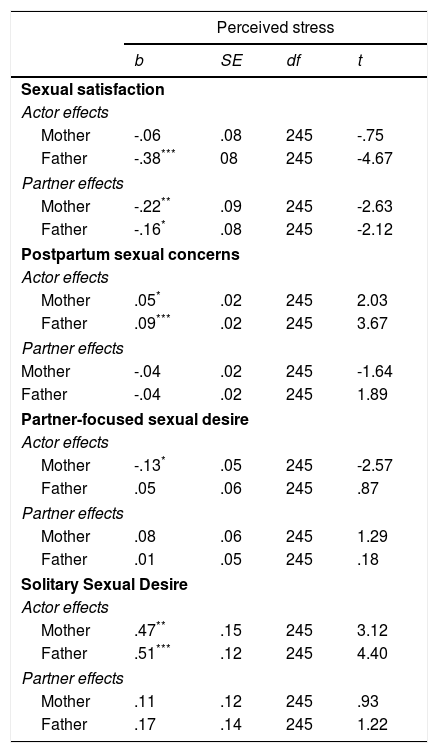

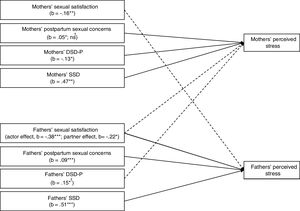

Results from the multilevel APIM are depicted in Table 3. This analysis yielded a statistically significant model explaining 20% of the variance of mothers’ perceived stress and 48% of fathers’ perceived stress. In line with our predictions, sexual well-being was associated with levels of stress in both members of the couple. When fathers reported greater sexual satisfaction, both they (actor effect) and their partners (i.e., mothers; partner effect) experienced lower perceived stress. When mothers reported greater sexual satisfaction, this was unrelated to their own levels of stress (actor effect) but was associated with fathers’ lower perceived stress (partner effect). When fathers and mothers endorsed highly distressing postpartum sexual concerns, they also reported greater levels of stress (actor effects), but no partner effects emerged. Regarding sexual desire, distinct patterns of results were found for partner-focused desire and solitary desire. Fathers’ partner-focused desire was not associated with their own or their partner's stress, but mothers’ greater levels of partner-focused desire were associated with their own lower levels of stress (actor effect). Conversely, for both mothers and fathers, greater solitary desire was associated with their own higher levels of stress (actor effects; see Figure 3).

Actor-partner Interdependence Model of sexual well-being on perceived stress postpartum.

| Perceived stress | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | df | t | |

| Sexual satisfaction | ||||

| Actor effects | ||||

| Mother | -.06 | .08 | 245 | -.75 |

| Father | -.38*** | 08 | 245 | -4.67 |

| Partner effects | ||||

| Mother | -.22** | .09 | 245 | -2.63 |

| Father | -.16* | .08 | 245 | -2.12 |

| Postpartum sexual concerns | ||||

| Actor effects | ||||

| Mother | .05* | .02 | 245 | 2.03 |

| Father | .09*** | .02 | 245 | 3.67 |

| Partner effects | ||||

| Mother | -.04 | .02 | 245 | -1.64 |

| Father | -.04 | .02 | 245 | 1.89 |

| Partner-focused sexual desire | ||||

| Actor effects | ||||

| Mother | -.13* | .05 | 245 | -2.57 |

| Father | .05 | .06 | 245 | .87 |

| Partner effects | ||||

| Mother | .08 | .06 | 245 | 1.29 |

| Father | .01 | .05 | 245 | .18 |

| Solitary Sexual Desire | ||||

| Actor effects | ||||

| Mother | .47** | .15 | 245 | 3.12 |

| Father | .51*** | .12 | 245 | 4.40 |

| Partner effects | ||||

| Mother | .11 | .12 | 245 | .93 |

| Father | .17 | .14 | 245 | 1.22 |

Note.

Actor–partner Interdependence Model of sexual well-being on perceived stress postpartum. Only significant effects are presented. Solid lines represent actor effects, dashed lines represent partner effects. DSD–P=Dyadic sexual desire (partner); SSD=Solitary sexual desire. †Effects altered upon controlling for relationship satisfaction.

* p < .05, ** p <.01, *** p <.001.

Additional analyses were conducted to control for potential confounding effects of variables related to postpartum stress. We analysed the association between perceived stress with potential covariates (child age, breastfeeding, maternal fatigue, relationship satisfaction and duration, and pain intensity during intercourse). Only pain intensity during intercourse (rmothers=.35; rfathers=.44) and relationship satisfaction (rmothers=-.50; rfathers=-.58), ps <.01, correlated significantly with perceived stress in both partners at r> .30. These variables were therefore entered as covariates into the main analyses. Pain intensity during intercourse did not significantly alter the observed pattern of findings; however, two effects differed when relationship satisfaction was controlled for. The previously significant actor effect of mothers’ sexual concerns on stress ceased to be significant (b=.04, SE=.02, t244=1.67, p=.096) and a partner effect emerged such that fathers’ higher partner-focused desire was associated with mothers’ higher perceived stress (b=.15, SE=.06, t244=2.45, p <.05). The inclusion of both covariates additionally explained 12% of mothers’ and 6% of fathers’ variance in postpartum stress.

DiscussionThis study examined the relationship between three key dimensions of postpartum sexual well-being—sexual satisfaction, sexual desire, and postpartum sexual concerns—and perceived stress in first-time parent couples. Significant associations were found for each sexual predictor which, taken together, indicated that greater sexual well-being was uniquely associated with new parents’ lower perceived stress, even when controlling for other factors relevant to postpartum stress (i.e., relationship satisfaction, pain during intercourse).

When mothers and fathers reported greater sexual satisfaction, fathers reported lower stress. When fathers were more sexually satisfied, mothers’ stress was also lower, but mothers’ sexual satisfaction was not linked to their own stress. These results are consistent with previously reported negative associations between both partners’ sexual satisfaction and fathers’ stress postpartum (Leavitt et al., 2017). After childbirth, mothers’ often cope with specific stressors related to birth and their bodies (e.g., breastfeeding, body image, genital healing) that may impact their sexuality differently from their partners’ (McBride & Kwee, 2017). Our findings suggest that, while coping with these stressors, mothers’ may use fathers’ sexual satisfaction as a proximal cue for their own lower stress through a partner-oriented coping process (Kenny et al., 2006). Fathers’ greater sexual satisfaction might also relate to their own behaviors towards the mother (e.g., showing more affection, being more empathic; Rosen et al., 2016), which could contribute to mothers’ feeling less overburden and stress. These findings are consistent with emotional capital theory (Feeney & Lemay, 2012), suggesting that partners who are more sexually satisfied are better able to cope with the novel changes and responsibilities of new parenthood, as evidenced by their lower stress.

Greater sexual concerns specific to the postpartum period were also associated with one's own greater feelings of stress for both mothers and fathers, further denoting the adverse impact that sexual concerns may pose to new parents’ overall well-being (Schlagintweit et al., 2016; Vannier, Adare, & Rosen, 2018). This result is in line with the transactional model of stress, which suggests that given the contextual challenges of postpartum, sexual changes might be perceived as exceeding couples’ coping resources, resulting in heightened stress (Ben-Zur, 2019). For mothers, sexual concerns ceased to associate with their own stress when relationship satisfaction was taken into account, suggesting that greater relationship satisfaction might be driving this effect for mothers. This effect is not surprising considering previous evidence linking sexual concerns and mothers’ relationship satisfaction postpartum (Schlagintweit et al., 2016) and the interdependence between sexual and relationship dimensions (McNulty et al., 2016; Sánchez-Fuentes et al., 2014). As new parents cope with many novel challenges across the postpartum, sexual concerns that are often novel (e.g., the impact of breastfeeding on breasts and on vaginal dryness) and in some cases unexpected (e.g., changes in self or partners’ sexual perception now that they are parents) might be taxing on new parents’ coping resources.

Previous research has observed inconsistent associations between new parents’ sexual desire and postpartum stress (Hipp et al., 2012; van Anders et al., 2013), but these studies examined sexual desire as a unidimensional construct perhaps obscuring more nuanced relationships. We addressed this limitation by examining whether sub-dimensions of sexual desire—sexual desire that is partner-focused vs. solitary—exerted distinct associations with new parents’ stress. Findings indicated that fathers’ partner-focused desire was not linked to stress levels, but when mothers reported greater partner-focused desire, they also reported lower stress. This finding contrasts with Hipp and colleagues’ (2012) study that found no association between mothers’ sexual desire and postpartum stress. The equivocal results could be attributable to methodologic differences, since Hipp and colleagues examined general sexual desire, i.e., not partner-focused desire, and retrospectively assessed women who had given birth within the last seven years.

When controlling for relationship satisfaction, unexpectedly, fathers’ greater partner-focused desire was associated with mothers’ greater stress. It is possible that new mothers may interpret fathers’ greater desire as an obligation or pressure to engage in sexual activity, or even feel guilty about declining sexual activity (Sutherland, Rehman, Fallis, & Goodnight, 2015), which can be perceived as stressful. Another concurrent explanation for this result concerns the degree of desire discrepancy between partners. Mothers, who reported lower desire than fathers, may feel more at ease with their own (lower) levels of partner-focused desire because they meet their expectations for the postpartum (i.e., decreased desire after childbirth may be seen as normative due to attributions such as recovering from pregnancy and childbirth, breastfeeding, or fatigue). However, they may feel less content with their partners’ desire towards them which, by being higher than their own, may violate their postpartum expectations (Roy, Schumm, & Britt, 2014), leading to lower satisfaction (Rosen et al., 2017; Sutherland et al., 2015) and greater stress.

Regarding solitary desire, when mothers and fathers reported greater desire to engage sexually by themselves, they also reported heightened stress, while no partner effects emerged. It might be that solitary desire covaries positively with stress because it can be used as a coping mechanism during this stressful transition, especially because solitary sexual activity doesn’t require individuals to integrate their partners’ needs. Sex can indeed serve to regulate stress (Ein-Dor & Hirschberger, 2012) and both men and women endorse stress reduction as a motive for sex (Meston & Buss, 2007).

Current results additionally extend prior research by demonstrating that sexual well-being explained more of the overall level of perceived stress for fathers than mothers. One possible reason for this difference is that men, more than women, use sex to provide relieve from stress (Meston & Buss, 2007). Another feasible explanation is that mothers, as the partner who gave birth, typically face a greater number of challenges (e.g., physical recovery, breastfeeding) that affect them both physically and psychologically (McBride & Kwee, 2017) and which contribute to their overall levels of stress. Taken together, these findings suggest a critical role of sexual well-being in fathers’ experience of stress postpartum, while denoting that mothers may benefit from greater support adjusting to the many competing demands after childbirth, including sexual ones.

The findings of this study should be considered in light of the following limitations. This study was correlational and we cannot determine the direction of causality. Although our hypotheses draw from prior theoretical and empirical research (e.g., Feeney & Lemay, 2012; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), as noted, the reverse direction of effects is also plausible, in such a way that greater stress postpartum leads to poorer sexual well-being in these couples. Future longitudinal studies should explore these temporal associations. Data were collected online using self-reports, and thus participation was limited to couples with access to online resources and who were interested in completing a study of this nature. All couples who participated in this study were in intimate, mixed-sex relationships, and were first-time parents to a healthy infant who was born at term. It is unknown whether results generalize to more diverse samples or to those who are faced with additional stressors (e.g., same-sex couples, adoptive parents, parents to an infant born preterm).

From a bigger picture perspective, and despite these limitations, this study highlights the interdependence between couple members’ experiences and the critical role of unique aspects of sexual well-being for understanding how couples perceive postpartum stress. This knowledge may be particularly useful for prevention and treatment efforts with new parent couples, by emphasizing the importance of considering both partners and identifying specific targets for intervention. Adding to previous treatments noting the importance of targeting postpartum sexual well-being (McBride, Olson, Kwee, Klein, & Smith, 2016), education and interventions aimed at helping new parents cope with stress are encouraged to integrate sexual well-being as an important component.

To help couples navigate the potential stressful character of this transition, professionals are advised to foster dyadic, in addition to individual, sexual well-being. One way of doing so is by providing couples with relevant information about postpartum sexuality, along with effective strategies to discuss and deal with their sexual worries, and their need to engage, or not engage, in sex (Muise et al., 2017). Communicating about sexual issues can be a difficult task for many couples (Sanford, 2003) but is often beneficial for both partners’ sexual and relational satisfaction (Jones, Robinson, & Seedall, 2018; Rancourt, Flynn, Bergeron, Rosen, 2017). Therefore, enhanced knowledge of what to expect regarding sexual changes postpartum, coupled with better communication about one's sexual concerns, could normalize new parents’ experiences, facilitate feelings of increased adjustment postpartum, and ultimately promote effective strategies to deal with them.

This work was supported by a Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology scholarship awarded to Inês M. Tavares (SFRH/BD/131808/2017; CPUP UID/PSI/00050/2013, POCI-01-0145-FEDER-0072), an IWK Health Centre Category A operating grant awarded to Natalie O. Rosen and Hera E. Schlagintweit, and by a Canadian Institutes for Health Research operating grant awarded to Natalie O. Rosen. The authors would like to thank Kristen Bailey and James Kim for their assistance with data collection, as well as the couples who participated in this research.