Dropout from psychological treatment is an important problem that substantially limits treatment effectiveness. A better understanding of this phenomenon, could help to minimize it. Therefore, we performed a systematic review of meta-analyses (MA) on dropout from psychological treatments to (1) determine the estimated overall dropout rate (DR) and (2) to examine potential predictors of dropout, including clinical symptoms (anxiety and depression) and sociodemographic factors.

MethodA literature search of the PubMed PsycINFO, Embase, Scopus and Google Scholar databases was conducted. We identified 196 MAs on dropout from psychological treatment carried out primarily in adult patients or mixed samples (adults and children) between 1990 and 2022. Of these, 12 met all inclusion criteria. Two forest plots were created to visualize the DR and the relationship between DR and the disorder.

ResultsThe DR ranged from 15.9% to 46.8% and was significantly moderated by symptoms of emotional disorders. The highest DR were observed in younger, unmarried patients, and those with lower educational and income levels.

ConclusionsDR in patients undergoing psychological treatment is highly heterogeneous, but higher in individuals presenting symptoms of anxiety and/or depression, especially the latter. Given that high DR undermine the effectiveness of psychological interventions, it is clear that greater efforts are needed to reduce dropout, particularly among individuals with symptoms of emotional disorders.

Emotional disorders are prevalent in the general population and constitute one of the main causes of morbidity and disability, imposing an enormous socioeconomic burden (Campo-Arias & Cassiani, 2008; Whiteford, 2015; Wittchen & Jacobi, 2005; Wittchen et al., 2011). Recent data show that anxiety and depression rates in the general population have increased by up to three and seven times, respectively, due to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health (Bueno-Notivol et al., 2021; Santabárbara et al., 2021), with a major negative impact on both men and women and across the affected countries (Cénat et al., 2021). Fortunately, psychological treatment—especially cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)—is an effective treatment for depression (Cuijpers et al., 2023) and other emotional disorders, particularly in primary care settings (Cuijpers et al., 2019; Seekles et al., 2013). Nonetheless, dropout rates (DR) in patients undergoing psychological treatment are generally high and thus many patients do not benefit from the proven efficacy of these interventions (Harvey & Gumport, 2015; Swift & Greenberg, 2012).

Premature termination of psychological treatment occurs when a patient has started therapy but abandons it before achieving a requisite level of improvement, recovering from the problems/ symptoms requiring therapy, or before completing the therapeutic goals (Hatchett & Park, 2003; Swift & Greenberg, 2012). Dropout has been defined quite broadly and encompasses a wide set of criteria such as the therapist's judgment of patient termination status, treatment duration, or number of sessions completed (Sharf, 2009; Wierzbicki & Pekarik, 1993). Initially, most researchers focused only the patient's role in treatment dropout. However, more recent research has assessed the influence of health care personnel on dropout, and it is now widely believed that the best way to understand the phenomenon is to use a system approach (Murphy et al., 2022; WHO, 2003; Zimmermann et al., 2017). In short, it has become evident that multiple interrelated factors determine treatment dropout and all of these factors should be considered when evaluating and attempting to improve DR (WHO, 2003).

Swift and Greenberg (2012) estimated that approximately one out of every five (20%) individuals abandon psychological treatment, although it is difficult to ascertain the true DR due to the lack of a single definition of this phenomenon and to the lack of a standardized approach to measuring treatment adherence. The factors considered most closely associated with adherence are those associated with the disorder itself (i.e., symptom severity, disability level, or the availability of effective treatments) (DiMatteo et al., 2007; WHO, 2003). However, the impact of these disorder-related factors depends on the extent to which these factors influence the patients' perception of risk, the importance of follow-up treatment, and the priority given to therapeutic adherence (WHO, 2003). For instance, anxiety and depression are important predictors of higher DR (Fernández-Arias et al., 2016; Henzen et al., 2016; Stubbs et al., 2016). In patients with anxiety disorders, the DR range is around 28-35%, with 50% of dropouts occurring during the first seven sessions (Fernández-Arias et al., 2016, 2019). Fernández-Arias et al. (2016, 2019) found that patients who are considered “poor adherers” tend to continue treatment, but perform worse on the execution of tasks with irregular attendance and late arrival to treatment sessions. The higher depression symptom severity was associated with early dropouts, while late dropouts could be related to the improvement experienced with the treatment; on the other hand, comorbid depressive and anxiety disorders and higher symptom severity were associated with higher dropout (Aderka et al., 2011; Lamers et al., 2012).

Clearly, high DR among patients receiving psychological treatment is a major issue. However, as some authors noted (Bentley et al., 2021; Swift and Greenberg, 2012), in order to remedy this situation, it is crucial not only to determine the true DR but also to identify the main reasons underlying treatment dropout. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO, 2003), various economic and social factors such as low socioeconomic status, low educational level, unemployment, and the lack of effective support networks can all significantly affect DR. Given the complex interrelation among the many factors that influence dropout, Karyotaki et al. (2015), sought to evaluate the combined impact of anxiety and depression symptoms and sociodemographic variables on DR, finding that several variables—notably sex (male), educational level (low), age (being young), and the presence of comorbid anxiety and depression symptoms—significantly increased the probability of dropping out of treatment.

Numerous primary studies and meta-analyses (MAs) have been performed to investigate this question. Although primary studies are essential, MAs provide a stronger level of evidence, since they collect the available knowledge about a given topic, provide a combined estimate of effect sizes, and can help to identify associations between moderating variables (Botella & Zamora, 2017). Moreover, MAs are not exempt from the risk of bias. For this reason, we believe that a systematic meta-review of the available MAs could provide the strongest data on dropout from psychological treatment and also help to better assess any conflicting data (Botella & Zamora, 2017; Botella & Sánchez-Meca, 2015).

It seems clear that when many MAs have already been published to examine the same—or quite similar—question, performing another MAs is unlikely to improve our understanding of a given effect. In this case an alternative approach is to carry out an "overview of reviews" or "umbrella review" (López-López et al., 2022), which are reviews of MAs rather than primary studies. This type of review can be considered a second level reviews. In these MAs some problems appear similar to those of the meta-analyses, but also new ones. However, this approach also provides new opportunities to investigate the variations observed in pooled estimates (López-López et al., 2022; Pollock et al., 2021; Schultz et al., 2018) and their association with moderators at the meta-analytical level. Thus, since the question of dropout from psychological treatment has already been addressed in several meta-analyses, we have adopted this approach for the present review and we will look in the literature for meta-analyses as the units of our work.

In this context, the aim of the present meta-review was to systematically evaluate the most relevant MAs in order to summarize the current state of the art understanding about DR from psychological treatment and the role played by key clinical symptoms (depression and anxiety) and sociodemographic variables. To do so, we performed a comprehensive literature search of the available MAs on this topic and selected those most relevant to these aims.

MethodThis was a systematic meta-review of MAs on dropout from psychological treatment. We included MAs that provided data on the DR from psychological treatment and on the association between DR and key clinical symptoms (anxiety and/or depression), social support and sociodemographic variables (age, sex, level economic, educational level, employment and marital status).

A literature search of the PubMed PsycINFO, Embase, Scopus and Google Scholar databases was performed. We reviewed all MAs published in English between the years 1990 and 2022. We searched for the following terms (key words or title): “adherence” or “attrition” or “dropout” or “termination” and “meta-analysis” and “psychological treatment” or “psychotherapy” and the study variables: “anxiety”, “depression”, “social support”, “age”, “sex”, “income level”, “socioeconomic status", “level of studies”, “education”, “employment status” and/or “marital status”.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) study design (MA), (2) study variable: dropout from psychological treatment, (3) DR reported, (4) study variables including any of the emotional symptoms and sociodemographic factors of interest, (5) study sample involving primarily adults (mixed samples of adults and children were permitted).

Exclusion criteria were: (1) dropout associated with medical illness, (2) DR not reported (i.e., effect size expressed as odds or risk ratios), (3) DR given for different types of treatment without providing the average DR for psychological treatment, (4) samples comprised only of adolescents or children but not adults.

We identified a total of 206 MAs. Of these, 10 were duplicates. Consequently, 196 MAs were selected for possible inclusion. These studies were then screened (title and abstract) to verify eligibility. Of these, 107 MAs were rejected for failing to meet the inclusion criteria. The most common reason for rejection was that the main study aim was to evaluate dropout from medications in chronic medical conditions, without evaluating or providing the DR for psychological treatment. The remaining 80 MAs were then further evaluated by reading the full text. Of those, we excluded (based on statistical and quality criteria) the MAs that included only minors, those that evaluated dropout related to the pharmaceutical dose of a medical treatment, and those conducted to evaluate proposed interventional strategies to improve adherence, among others.

A total of 12 MAs met all inclusion criteria and were included in this meta-review. A flowchart of the study selection process (PRISMA guidelines) is presented in Fig. 1.

We created a forest plot to graphically illustrate the DR from psychological treatment in the included MAs. This type of graphic allows readers to assess the information from the individual studies (in this case, MAs) at a glance. Forest plots provide a simple visual representation of the variation between the results of the different studies, and an estimate of the overall effect obtained by each MA from its primary studies (Botella & Zamora, 2017; Lewis and Clarke, 2001). For this, the confidence intervals (CI) of the DR must be symmetric. However, in some cases, the CIs were asymmetric, either because the DR was calculated as simple percentages, or logit transformations were used (Newcombe, 2012). For these asymmetric CIs, we determined approximate intervals by calculating the standard error from the CI limits (upper and lower bounds) to determine the mean. Next, the standard error was calculated to obtain a forest plot using the R Metafor package (Viechtbauer, 2010).

Finally, we assessed the relationship between DR and anxiety and/or depression symptoms, and sociodemographic variables.

ResultsA total of 12 MAs (1632 primary studies) were included in this meta-review, including a total sample of more than 151,213 patients (k = 10; two studies did not include the total number of patients) (Sharf, 2009; Wierzbicki & Pekarik, 1993). The true sample size is somewhat lower because some primary studies have been included in more than one MA. Although the terms dropout or adherence are often used to express the same concept, we elected to use the dropout construct because the MAs included here all used the same term. By contrast, none of the MAs that used the term “adherence” met the inclusion criteria (focused mainly in patients with certain physical illnesses and/or using certain medications). Most of the MAs included studies that evaluated the efficacy of psychological treatment for a mixture of various disorders (k=5). However, some MAs were performed specifically to investigate psychological treatment for a specific disorder, such as depression (k=3), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (k=2), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) (k=1), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) (k=1). Most MAs included both individual and group treatment formats (k=7), although three MAs included only individual treatment formats (k=3). In the remaining two MAs, one included studies evaluating individual, group or online treatment modalities (k=1), while the final MA evaluated only online treatments (k = 1). In most of the MAs (k = 8), the studies included only adults. In the remaining four MAs, mixed samples of both adult and children were included (k = 4). See Table 1.

Summary of the meta-analyses included in this meta-review

| Study | k | N | Diagnosis | Treatment format |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wierzbicki and Pekarik (1993) | 125 | - | Various disorders | Individual and group |

| Sharf (2009) | 110 | - | Various disorders (DR disaggregated by disorder) | Individual |

| Swift and Greenberg (2012) | 669 | 83834 | Various disorders (DR disaggregated by disorder) | Individual and group |

| Imel, Laska, Jakupcak and Simpson (2013) | 42 | 1850 | PTSD | Individual and group |

| Hans and Hiller (2013) | 34 | 1880 | Depression | Individual and group |

| Cooper and Conklin (2015) | 54 | 5852 | Depression | Individual |

| Fernández, Salem, Swift and Ramtahal (2015) | 115 | 20995 | Various disorders (DR disaggregated by disorder) | Individual, group and online |

| Gersh et al. (2017) | 45 | 2224 | GAD | Individual |

| Swift, Greenberg, Tompkins, and Parkin (2017) | 182 | 17891 | Various disorders | Individual and group |

| Leeuwerik, Cavanagh and Strauss (2019) | 123 | 5627 | OCD | Individual and group |

| Lewis, Roberts, Gibson and Bisson (2020) | 115 | 7724 | PTSD | Individual and group |

| Torous, Lipschitz, Ng and Firth (2020) | 18 | 3336 | Depression | Online |

Abbreviations: PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder, GAD = generalized anxiety disorder, OCD = obsessive compulsive disorder

The various MAs included in this study used slightly different definitions of the term “dropout”. The first MA by Wierzbicki and Pekarik (1993) differentiated between termination due to failure to attend a scheduled session, therapist judgment, and number of sessions attended.

Later MAs defined dropout as failure to complete the treatment protocol (Gersh, 2017; Imel et al., 2013) and having attended at least one session (Fernández et al., 2015; Hans & Hiller, 2013; Leeuwerik et al., 2019; Swift & Greenberg, 2012; Swift et al., 2017). The MA by Cooper and Conklin (2015) defined dropout as failure to complete the treatment, but included any patient who refused randomization, never attended a session, stopped attending sessions, or withdrew consent before completing the designated treatment. The MA by Lewis et al. (2020) and Torous et al. (2020) defined dropout as not attending the post-evaluation session. Sharf (2009) included the definition of dropout as a study variable.

Nearly all of the MAs (k=11) refer to dropout from psychological treatment without specifying whether the patients also received concurrent pharmacological treatment; in fact, only one MA (Swift et al., 2017) made this distinction. The MAs included in this meta-review defined “psychological treatment” in different ways. That is, some specified that it referred to only the CBT (Fernández et al., 2015; Hans & Hiller, 2013; Leeuwerik et al., 2019), while others included only studies that consisted of psychological treatment patients but not therapy analogues (i.e., couple or family therapy, self-help, or technology based interventions) (Cooper & Conklin, 2015; Sharf, 2009; Swift & Greenberg, 2012; Swift et al., 2017; Wierzbicki & Pekarik, 1993). The MAs carried out by Imel et al. (2013) and Gersh (2017) did not specifically define psychological treatment. Lewis et al. (2020) included any psychological therapy aimed at reducing symptoms or any psychosocial intervention (e.g., psychoeducation or relaxation training) with the same aim. Torous et al. (2020) evaluated smartphone-based interventions such as self-help and mindfulness apps, smartphone platforms for connecting individuals with health services, therapy apps, and mood tracking apps.

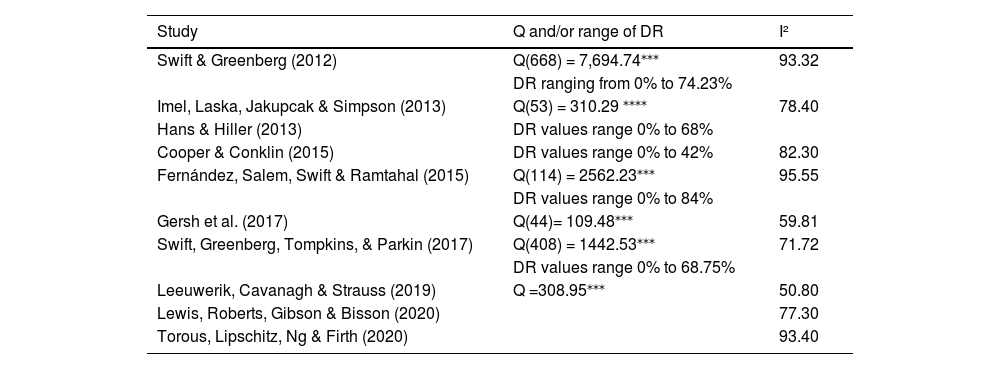

Dropout ratesWe created two forest plots to graphically show the DR reported in each of the 12 MAs. Our original aim was to create a forest plot of the general estimates of the DR; however, since 11 of the 12 MAs (except Leeuwerik et al., 2019) provided a significant amount of data on DR according to the kind of disorder, we decided to include a second forest plot disaggregated by disorder. The availability of these data allowed us to plot differences in the DR for various disorders, including anxiety disorder, OCD, PTSD, comorbid anxiety and depression, depression, eating disorder, personality disorder, psychotic disorder, and substance abuse. Most of the MAs in this study assessed heterogeneity using the Q test (Hedges & Olkin, 1985), to check for evidence of statistically significant heterogeneity between studies. The related I² statistic (Higgins & Thompson, 2002) was used to describe as a percentage the degree to which expressed the observed variability was due to variability in the true effects. The high degree of heterogeneity found in this set of MAs (Table 2) suggests that true differences in dropout from psychological treatment may differ depending on the potential moderators. Fig. 2 presents the DR estimates for each of the 12 MAs. Fig. 3 shows the estimated DR disaggregated by disorder. Table 2 presents the heterogeneity in the MAs.

Heterogeneity statistics: Q test for homogeneity or range of DR values and I2.

| Study | Q and/or range of DR | I² |

|---|---|---|

| Swift & Greenberg (2012) | Q(668) = 7,694.74⁎⁎⁎ | 93.32 |

| DR ranging from 0% to 74.23% | ||

| Imel, Laska, Jakupcak & Simpson (2013) | Q(53) = 310.29 ⁎⁎⁎⁎ | 78.40 |

| Hans & Hiller (2013) | DR values range 0% to 68% | |

| Cooper & Conklin (2015) | DR values range 0% to 42% | 82.30 |

| Fernández, Salem, Swift & Ramtahal (2015) | Q(114) = 2562.23⁎⁎⁎ | 95.55 |

| DR values range 0% to 84% | ||

| Gersh et al. (2017) | Q(44)= 109.48⁎⁎⁎ | 59.81 |

| Swift, Greenberg, Tompkins, & Parkin (2017) | Q(408) = 1442.53⁎⁎⁎ | 71.72 |

| DR values range 0% to 68.75% | ||

| Leeuwerik, Cavanagh & Strauss (2019) | Q =308.95⁎⁎⁎ | 50.80 |

| Lewis, Roberts, Gibson & Bisson (2020) | 77.30 | |

| Torous, Lipschitz, Ng & Firth (2020) | 93.40 |

Forest plot with specific estimates of dropout rates disaggregated by disorder

Initially, we selected a series of potential moderators to determine their association with dropout. Apart from the disorder already disaggregated in the forest plot, social support and sociodemographic factors (age, sex, economic level, level of education, employment status, and marital status) were also included. After reviewing the included MAs, we removed social support as insufficient data was found for this variable.

Symptoms of emotional disordersMultiple studies have found that the specific diagnosis moderated the DR. Early studies found a high overall DR (35%). By diagnosis, the DR was 44% in patients diagnosed with depression, and 25% and 22% in patients with PTSD and anxiety, respectively (Sharf, 2009). In a later MA, Swift and Greenberg (2012) found a general DR of 19.7%; the rate for anxiety, mood disorders, and PTSD were 16.2%, 17.4%, and 20.5%, respectively. Later studies, such as the MA by Fernández et al. (2015), also found a significant association between diagnosis and dropout, with a general DR of 26.2%; the DR for different disorders were as follows: anxiety disorder (19.6%), PTSD (27.2%), comorbid depression and anxiety (28%), and depression (36.4%). Gersh (2017) found a significant association between dropout and GAD, in which 1 in 6 patients with this disorder dropped out. DR are highly variable, but the minimum rate is approximately 15% (Table 3). This finding confirms that DR is a real and persistent problem. In general, at least one out of six patients will not benefit from therapy due to dropout. The DR is higher for some disorders than for others. More specifically, the DR was higher for depression than for anxiety disorders in all of the MAs assessed.

Association between symptoms of emotional disorders and dropout.

| Study | Conclusion |

|---|---|

| Variable: Anxiety | |

| Swift and Greenberg (2012) | DR significantly associated with anxiety symptoms |

| Fernández et al. (2015) | DR significantly associated with anxiety symptoms |

| Variables: Comorbid Depression and Anxiety | |

| Fernández et al. (2015) | DR significantly associated with symptoms of comorbid anxiety and depression |

| Variable: Depression | |

| Swift and Greenberg (2012) | DR significantly associated with depression symptoms |

| Fernández et al. (2015) | DR significantly associated with depression symptoms |

In studies that have evaluated dropout data for emotional disorders, some authors focus on symptomatology while others refer to severity. In this case, the severity would be a variable within the symptomatology, one variable within another, this is a nesting variable, and we preferred to separate it and differentiate it from symptoms of emotional disorders.

The results reported in these MAs regarding the association between dropout and symptom severity varied substantially. Only one of the three MAs that evaluated this moderating variable found an association. Sharf (2009) found a moderate to small effect size for the severity of depression (d=.28) and anxiety (d=.24), which indicates an association between symptom severity and DR. However, those authors did not specify whether symptom severity (greater or lesser) was associated with a higher DR. By contrast, Gersh et al. (2017) did not observe any significant association between GAD symptom severity (regardless of the rater [patient or clinician]) and dropout. Similarly, in the study by Leeuwerik et al. (2019), the severity of comorbid anxiety and depression symptoms, or depression alone, did not moderate dropout (Table 4).

Association between symptom severity and dropout rate.

| Study | Conclusion |

|---|---|

| Variable: Anxiety | |

| Sharf (2009) | DR significantly associated with severity of anxiety symptoms |

| Gersh et al. (2017) | DR not significantly associated with severity of GAD symptoms |

| Variables: Comorbid Depression and Anxiety | |

| Leeuwerik, Cavanagh and Strauss (2019) | DR not significantly associated with severity of comorbid anxiety and depression symptoms |

| Variable: Depression | |

| Sharf (2009) | DR significantly associated with severity of depression symptoms |

| Leeuwerik, Cavanagh and Strauss (2019) | DR not significantly associated with severity of depression symptoms |

We found highly heterogeneous results in terms of the impact of sociodemographic variables on DR. For example, some of the MAs found that younger patients had a higher risk of dropout than older patients (Wierzbicki & Pekarik, 1993), with significant difference but small effect sizes in the studies by Sharf (2009) and Swift and Greenberg (2012). However, other authors found that age was not a predictor of the DR (Cooper & Conklin, 2015; Gersh, 2017; Leeuwerik et al., 2019; Torous et al., 2020). See Table 5.

Association between age and sex and dropout.

| Study | Conclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| Association between age and dropout | Association between sex and dropout | |

| Wierzbicki and Pekarik (1993) | DR not significantly associated with age | DR not significantly associated with sex |

| Sharf (2009) | DR higher in younger patients | DR increases in line with a higher proportion of women in the sample |

| Swift and Greenberg (2012) | DR higher in younger patients | DR increases in line with a lower proportion of women in the sample |

| Cooper and Conklin (2015) | DR not significantly associated with age | DR not significantly associated with sex |

| Gers et al. (2017) | DR not significantly associated with age | DR not significantly associated with sex |

| Leeuwerik et al. (2019) | DR not significantly associated with age | DR not significantly associated with sex |

| Lewis et al. (2020) | - | DR not significantly associated with sex |

| Torous et al. (2020) | DR not significantly associated with age | DR not significantly associated with sex |

Similarly heterogenous results were observed with regard to the influence of sex. Of the eight MAs that assessed this variable, two found a significant association with treatment dropout (Sharf, 2009; Swift & Greenberg, 2012) but with opposite results. Sharf (2009) found that the DR increases in line with the proportion of women in the sample; by contrast, Swift and Greenberg (2012) found that higher DR were associated with fewer female participants. Wierzbicki and Pekarik (1993) also found the same association, with women being more likely to drop out of treatment than men, but this association did not reach statistical significance. The others MAs that evaluated the influence of this variable on dropout (Cooper & Conklin, 2015; Gersh, 2017; Leeuwerik et al., 2019; Lewis et al., 2020; Torous et al., 2020) concluded that sex does not appear to be a predictor of the DR (Table 5). In short, the evidence regarding the role of sex in DR is inconclusive.

Two of the Mas reached the same conclusion regarding the impact of educational level on dropout, both concluding that there is a significant association between lower educational level and a higher risk of dropping out (Wierzbicki & Pekarik, 1993; Sharf, 2009). On the other hand, in three Mas—Swift and Greenberg (2012), Leeuwerik et al. (2019) and Lewis et al. (2020)–the educational level (mean years of studies or the percentage of university students) was not a significant predictor of DR. See Table 6.

Association between level of education and dropout.

| Study | Categorization | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Wierzbicki and Pekarik (1993) | Mean years of study | DR higher in samples with a lower level of education |

| Sharf (2009) | % Higher education | DR higher in samples with a lower level of education |

| Swift and Greenberg (2012) | Average years of education % University | DR not significantly associated with level of education |

| Leeuwerik, Cavanagh and Strauss (2019) | Mean years of education | DR not significantly associated with level of education |

| Lewis, Roberts, Gibson and Bisson (2020) | % University | DR not significantly associated with level of education |

The influence of marital status was consistent across these MAs. Two studies found a significant association between dropout and marital status (Sharf, 2009; Swift & Greenberg, 2012), with similar results. Sharf (2009) found that the DR is lower in samples with a higher percentage of married or cohabitating people, and Swift and Greenberg (2012) found that the DR was higher in samples with a lower percentage of people who were married or in a committed relationship. Even so, several other authors found no significant association between marital status and dropout (Cooper & Conklin, 2015; Leeuwerik et al., 2019; Wierzbicki & Pekarik, 1993). See Table 7.

Association between marital status and dropout.

| Study | Categorization | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Wierzbicki and Pekarik (1993) | % Married | DR not significantly associated with marital status |

| Sharf (2009) | % Married/ cohabitating | DR lower in samples with a higher percentage of married individuals |

| Swift and Greenberg (2012) | % Married/ or in a committed relationship | DR higher in samples with a lower percentage of married individuals |

| Cooper and Conklin (2015) | % Married/ cohabitating | DR not significantly associated with marital status |

| Leeuwerik, Cavanagh and Strauss (2019) | % Married/ cohabitating | DR not significantly associated with marital status |

Only two MAs included in this meta-review assessed the impact of employment status on DR, and neither found any significant association (Leeuwerik et al., 2019; Swift & Greenberg, 2012).

Only one MA (Wierzbicki & Pekarik, 1993), assessed income level as a moderator of dropout from psychological treatment. That study found a significant association, with DR increasing in line with lower income levels.

DiscussionDropout definitionIn the present work, we evaluated dropout from psychological treatment and the role of moderating factors. DR were highly heterogeneous, but typically around 20–30%, depending on the specific disorder and other factors. Most of the MAs showed a DR between 15.9 and 26.2%, with only two studies reporting higher rates: 46.8% in the MA conducted by Wierzbicki and Pekarik (1993) and 35.3% in the study by Sharf (2009). As Wierzbicki and Pekarik (1993) observed, DR vary greatly depending on the definition of dropout. For instance, more conservative studies, which define dropout as missing the last treatment session, have reported substantially lower DR than studies in which dropout was left to the therapist's judgment or defined as the number of sessions attended. Another factor influencing the wide DR reported in these MAs is the methodological approach used by Wierzbicki and Pekarik, who were the first to conduct a MA to evaluate this phenomenon. Those authors did not use a standardized definition of dropout and, as the authors themselves noted in the conclusion, the study included an excessive number of sociodemographic factors (e.g., country of study, diagnosis or study design). In fact, the authors suggested that future research should focus less on sociodemographic variables and more on patient and therapist-related variables such as the therapeutic alliance, which has recently been associated with a lower risk of dropout (Murphy et al., 2022). Wierzbicki and Pekarik also noted a need to carefully consider the operational definition of dropout. However, in the MA by Sharf (2009), the definition of dropout was not a predictor of DR. The high DR in that study may be attributable to reliance on the Wierzbicki and Pekarik Study (1993), as Sharf averaged the DR with variables such as therapeutic alliance and patient variables (self-efficacy, motivation, and expectations). Wierzbicki and Pekarik also noted a significant difference between the DR reported by studies that included different clinical diagnoses, although later works found that the diagnosis is not predictive of the DR (Ong et al., 2018); however, not all incised on this difference of diagnosis. Wierzbicki and Pekarik point out that the results should be interpreted with caution because not all studies reported a primary diagnosis, and the studies that did so may not be representative of the broader study population. Over time, the definition of dropout has become standardized, as has the design of studies on dropout.

Main findingsThe data obtained in this meta-review indicate that symptoms of emotional disorders are significantly associated with the psychotherapy dropout (Swift & Greenberg, 2012), a finding that is consistent with results reported by other authors (Fernández et al., 2015; Fernández-Arias et al., 2016; Karyotaki et al., 2015). The DR for depression ranges from 17.4% to 44%, and 16.2% to 22% for anxiety. These data suggest that anxiety leads to less dropout than depression, especially given that the maximum DR for anxiety is 28%, and then only with comorbid depression. The WHO (2003) has warned of the potential impact of these disorders on treatment adherence, recommending that every effort should be made during interventions in patients with emotional disorders to check for the presence of depression due to its prevalence and negative effect on adherence.

We found that several sociodemographic variables moderate DR from psychological treatment. Across the included MAs, the findings regarding the role of age were relatively consistent (DR appear to decrease with age), although some of the studies did not find any association (Cooper & Conklin, 2015; Gersh, 2017; Leeuwerik et al., 2019; Ong et al., 2018; Torous et al., 2020). However, among those that did find a relationship between age and dropout, the association was always in the same direction, with younger people being less adherent (Sharf, 2009; Swift & Greenberg, 2012). Several other studies have also found that younger age is associated with higher DR (Cooper et al., 2016; Henzen et al., 2016; Zimmermann et al., 2017), which was also shown in the MA by Karyotaki et al. (2015), in which the likelihood of dropping out decreased significantly for every four-year increase in age. Bennemann et al. (2022) recently compared different machine-learning algorithms to identify the best predictors of dropout, one of which was younger age, whose relative importance to the model was > 90%).

The influence of sex on DR is more ambiguous. In general, the data seem to suggest that there is no significant association between sex and dropout (Cooper & Conklin, 2015; Gersh, 2017; Leeuwerik et al., 2019; Lewis et al., 2020; Torous et al., 2020; Wierzbicki & Pekarik, 1993). However, some contradictory findings have been reported. For example, Sharf (2009) found that women were more likely to drop out of psychological treatment than men (with a small effect size); by contrast, Swift and Greenberg (2012) found that the percentage of women in a given sample was a significant predictor of DR (i.e., a lower percentage of women in the sample predicts higher DR); by contrast, other studies (e.g., Zimmermann et al., 2017) and the MA by Kayotaki et al. (2015) found that men have a higher risk of dropping out.

Most data on the role of educational level conclude that there is a significant association between lower educational levels and higher DR (Kayotaki et al., 2015; Lewis et al., 2020; Sharf, 2009; Swift & Greenberg, 2012; Wierzbicki & Pekarik, 1993; Zimmermann et al., 2017), a finding that is also supported by the recent study by Bennemann et al. (2022), who found that lower education level is one of the main predictors of dropout.

The data on the role of marital status appear to be relatively consistent across these MAs, with three MAs (Sharf, 2009; Swift and Greenberg, 2012; Wierzbicki & Pekarik, 1993) finding an association between marital status and dropout (unmarried people have higher DR); however, this association did not reach statistical significance in one of those studies (Wierzbicki & Pekarik, 1993). In the two MAs in which the association was significant, the data were similar. Sharf (2009) found a lower DR in married patients than in unmarried patients, while Swift and Greenberg (2012) found that higher DR were associated with samples with a lower percentage of individuals who were married or in a committed relationship. In other words, there is an inverse relationship between DR and marital status (percentage of married or engaged). Although none of the MAs that we reviewed evaluated the role of social support on dropout from psychological treatment, we did find several MAs that evaluated the association between this variable and adherence to medical treatment. DiMatteo (2004) found that being married was associated with a modestly higher adherence, with a dropout risk that was 1.13 times higher among unmarried versus married individuals. This finding may explain the association between marital status and dropout, in that the support provided by the partner could reduce dropout. However, DiMatteo also found that other types of social support (functional support) have a significantly stronger association with adherence. Subsequent studies also found that functional (but not structural) social support was associated with adherence (Magrin et al., 2015), which is in line with the conclusion reached by DiMatteo (2004), who stated “the mere presence of other people does not matter as much as the quality of relationships with them” (p. 212). Thus, marital status may correlate with functional social support in the couple, moderating its relationship with DR.

Only two MAs assessed the impact of employment status, with neither observing any association with dropout (Leeuwerik et al., 2019; Swift & Greenberg, 2012), a finding that is consistent with the conclusions reported by Karyotaki and colleagues (Karyotaki et al., 2015).

Wierzbicki and Pekarik (1993) found that income level was significantly associated with dropout. More specifically, they found that DR have an inverse relation to income level (higher rates among groups with lower income levels), most likely because people with low socioeconomic status have less financial availability to receive treatment.

Others moderators of dropoutIn the present work, for practical purposes, the study variables were limited to symptoms related to emotional disorders and sociodemographic variables; however, the MAs included in this meta-review evaluated numerous variables in an effort to better understand treatment dropout. For example, many of the MAs considered symptom severity. Among the various MAs that evaluated the influence of anxiety and depression symptoms on dropout (Fernández et al., 2015; Swift and Greenberg, 2012), several also studied the impact of symptom severity of these disorders on dropout (Gersh et al., 2017; Leeuwerik et al., 2019; Sharf, 2009). Sharf (2009) found a significant association between anxiety and depression symptom severity and DR. By contrast, the meta-regression results included in two of these MAs (Gersh, 2017; Leeuwerik et al., 2019) show that none of the following variables—severity of anxiety symptoms, depression, or comorbid anxiety and depression—appear to moderate DR. The latest findings regarding the possible association between diagnosis and dropout indicate that DR did not differ according to the diagnostic method (clinical or self-reported diagnosis), in contrast to the finding described by Torous et al. (2020) for depression. Many of the MAs included in this meta-review have analyzed other factors related to dropout, such as the number of sessions. Imel et al. (2013) reported that each additional therapy session was associated with a one percentage point increase in the predicted DR; thus, the number of sessions is associated with a higher DR. There appears to be positive, linear association between treatment duration and dropout (Cooper & Conklin, 2015), although Fernández et al. (2015) found the opposite effect, in which the DR decreased as the number of sessions increased (range: 5 to 48 sessions). Nonetheless, other studies have not found any association between dropout and the number of sessions (Gersh, 2017) or session frequency (Ong et al., 2018).

Wierzbicki and Pekarik (1993) assessed a range of different factors to better understand dropout, finding no difference in DR according to type of treatment (individual or group), treatment setting (university, private clinic, public clinic, others), type of patient (adult, mixed, children), or the characteristics of the therapist (age, ethnicity, degree, or years of experience). Nevertheless, they still concluded that adults and children should be evaluated separately.

In terms of treatment format, Fernández et al. (2015) found that one out of four patients (individual or group therapy) and one out of three (online therapy) dropped out, however, these small differences were not statistically significant. Leeuwerik et al. (2019) found that group therapy was associated with a lower DR than individual therapy. In fact, that variable was the only significant moderator of dropout. By contrast, in two other studies—Lewis et al. (2020) and Ong et al. (2018)—group format was not associated with higher dropout. Moreover, in the study by Ong and colleagues, the therapy format, session count, and session frequency were not significant predictors of DR.

Treatment orientation has also been evaluated due to its potential to influence dropout. Cooper and Conklin (2015) found no significant association between treatment orientation and dropout, neither did Torous et al. (2020), who observed that the addition of CBT or mindfulness techniques to the treatment did not differ from did not apply those interventions.

Swift and Greenberg (2014) assessed the role of the specific disorder, type of treatment, and DR based on data from their 2012 study (Swift & Greenberg, 2012), finding that the treatment approach influenced DR in patients with depression, eating disorders, and PTSD. By contrast, the treatment approach had no significant effect on DR in patients with panic disorder or GAD (Swift & Greenberg, 2014; Gersh, 2017), nor on treatments for grief, borderline personality disorder, OCD, other personality disorders, psychotic disorders, social phobias, or somatoform disorders. Swift and Greenberg (2014) found that integrative approaches were associated with a lower DR than CBASP (Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy) cognitive therapy, CBT, interpersonal psychotherapy, solution-focused therapy, and psychotherapy support.

Clinical implicationsOne of the major challenges of the present review has been to identify MAs whose sole aim was to evaluate the impact of psychological treatment on dropout, mainly because most of the published research studies have focused on dropout from medical treatment. One of the MAs in this meta-review—Swift et al. (2017)—assessed the impact of pharmacological treatment on dropout. Those authors differentiated between several patient groups, as follows: pharmacotherapy alone, psychotherapy alone, pharmacotherapy plus psychotherapy, and psychotherapy plus pill placebo. The authors found a treatment refusal rate (among patients who had already agreed to receive treatment) of 8%, with a 20% DR among patients who started treatment. This finding indicates that one of every five patients did not adhere to treatment, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies (Swift & Greenberg, 2012). The refusal rate for pharmacological treatment was substantially higher than the psychotherapy refusal rate in patients with social anxiety disorders (1.97 times more), panic (2.79 times) and depression (2.16 times). The DR was also higher for pharmacotherapy compared to psychotherapy. For example, in depression disorder, patients who received pharmacotherapy were 1.26 times more likely to drop out than those who received psychological treatment. In the two studies by Swift and Greenberg (2012, 2014), the authors emphasized the importance of consider dropout data when selecting and/or administering a given intervention. Even if a given treatment is highly effective, it is of little use if a high proportion of patients fail to complete the treatment program. Ideally, both efficacy and dropout should be considered. Those authors point out that professionals do not need to change their therapeutic orientation, but rather that they should consider incorporating integrative models, which have the lowest DR.

LimitationsThis meta-review has several important limitations. First, although we sought to make the review as comprehensive as possible, we may have failed to locate some studies on the DR to psychological treatment during the literature search. Second, as Cuijpers et al. (1998) noted in their early MA on psychological treatment dropout, it is important to include the DR as an indicator of MA results since many studies evaluate dropout results in terms of effect size. In this regard, due to our focus on DR, we may have failed to include important data about dropout because the studies reported those data in other formats (e.g., effect size, relative risk, odds ratio). Third, one of the main advantages of MAs is that they bring together a large body of data about a topic in a single study. Similarly, while a new MA adds the most recent data, the accumulated knowledge may remain unchanged. Another limitation of this meta-review is that some of the MAs included the same primary studies. Unfortunately, given that it would not be feasible to check the more than 1600 studies included in those 12 MAs, we do not know the actual total number of patients and primary studies on which the results are based.

ConclusionDropout from psychological treatment remains a remarkably important problem that needs to be addressed by strengthening efforts to improve patient adherence. In this meta-review, we created a forest plot to graphically illustrate the DR reported in 1,632 primary studies collected in the 12 MAs, which ranged from 15.9% to 46.8%. We found a strong significant association between symptoms of emotional disorders and dropout, especially with depression; however, the association between symptom severity and dropout is less clear. The impact of sociodemographic factors on dropout also yielded heterogeneous results. The association between sex and dropout can be considered inconclusive given the contradictory findings, in which some MAs found no association with dropout whereas others reported a significant association. Although not all studies support the association between age and dropout, the data indicate that young people are more likely to drop out of treatment. In the MAs that found a consistent association between educational level and dropout, the DR was higher in patients with lower educational levels. In terms of marital status, the available data indicate that DR is lower in married individuals. Despite the limited research on the relationship between income level and dropout, the available data show a significant association with dropout, with lower income associated with higher DR. Employment status does not appear to be associated with dropout, but no definitive conclusion can be made in this regard due to the scant data available (few studies).

We believe that the findings presented here will help to clarify the phenomenon of dropout and thus improve clinical practice. Our data suggest that efforts to reduce dropout from psychological treatment should focus on modifiable factors, such as anxiety and depression symptoms, given that the body of evidence confirms these two variables—regardless of severity—have the most influence on dropout from psychological treatment.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

ContributorsAuthors A and D designed the work. Authors A and B conducted literature searches and provided summaries of previous research studies. Author A wrote the first draft of the manuscript and authors B and C revised and improved the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

We would like to acknowledge Professor Juan Botella for his assistance with technical support, without which this work would not have been possible.