There are a vast number of studies on the relationship between R&D and exports. However, the results are not always clear-cut. This study evaluates whether, in the case of a small, open and peripheral country in which exports are the engine of economic growth despite a noticeable laggardness in terms of R&D, the firms’ R&D impacts on and/or is influenced by their exports, as well as whether the interrelation between R&D and exports impacts on the performance of firms. Using an unique dataset comprising all (more than 340 thousands) non-financial companies based in Portugal, over the period 2006-2012, estimations based on bivariate probit models, which provide the simultaneous estimation of the two decisions (R&D and exports), taking into account the correlation between the estimation errors of the equations for R&D and exports, confirm there is complementarity between R&D and exports, which means that engaging in R&D activities will increase the firm's probability of engaging in export activities. Additionally, engaging in export activities will also increase the probability of engaging in R&D. The results also provide support for the hypothesis that more productive firms self-select into exporting activities and also provide support for the learning-by-exporting hypothesis. Finally, based on a panel model we further found that R&D and exports have a positive effect on sales growth, which is enhanced when both activities occur simultaneously.

Hay un gran número de estudios sobre la relación entre la I+D y las exportaciones. Sin embargo, los resultados no siempre son bien definidos. Este estudio evalúa si en el caso de un país pequeño, abierto y periférico —en el que las exportaciones son el motor del crecimiento económico a pesar de un retraso notable en términos de I+D— la I+D que realizan las empresas impacta en o está influenciada por sus exportaciones, así como si la interrelación entre la I+D y las exportaciones impacta el desempeño de las empresas. Mediante un conjunto de datos único que comprende todas las empresas no financieras con sede en Portugal (más de 340 miles), para el periodo 2006-2012, las estimaciones basadas en modelos probit bivariados, que proporcionan la estimación simultánea de las dos decisiones (I+D y exportaciones), tomando en cuenta la correlación entre los errores de estimación de ambas ecuaciones, confirman que hay complementariedad entre la I+D y las exportaciones, lo que significa que la participación en las actividades de I+D aumentará la probabilidad de la empresa de participar en las actividades de exportación. Además, la participación en actividades de exportación también aumentará la probabilidad de participar en la I+D. Los resultados también proporcionan apoyo a la hipótesis de que las empresas más productivas autoseleccionan las actividades exportadoras y a la hipótesis de aprendizaje mediante la exportación. Finalmente, basados en un modelo de panel hemos encontrado que la I+D y las exportaciones tienen un efecto positivo sobre el crecimiento de las ventas, que se ve reforzado cuando se producen simultáneamente ambas actividades.

The export capacity of a company is often considered an indicator of its competitiveness and success (Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013), as it is generally assumed that an exporting firm tends to be more productive than a non-exporter (Silva, Afonso, and Africano, 2013).

The differences between exporters and non-exporters have recently been associated with their willingness to invest in intangibles, including Research & Development (R&D). Specifically, Aw, Roberts, and Xu (2011) identified investment in R&D and adoption of technology as relevant factors in explaining the higher productivity of exporters compared to non-exporters. These authors consider that the decisions to export and invest in R&D or technology are interdependent and both influence the future profitability of companies.

The theoretical literature on the relationship between exports and R&D has focused on the firms’ process of learning through internationalization, including the impact of such learning on innovation (Girma, Gorg, and Hanley, 2008). According to Girma, Gorg, and Hanley (2008), in order to compete in international markets, exporters have to invest in technology to meet the needs of a more sophisticated demand. Exporting companies also have access to sources of knowledge that are not available in the domestic market (Alvarez and Robertson, 2004). These factors lead exporters to improve their knowledge base and hence increase their innovative capacity and ability to create better quality innovations (Golovko and Valentini, 2011). Regarding R&D, the higher the firms’ investment, the more likely their products and/or services become innovative and competitive, positively impacting on exports and thus gaining competitive advantage (Lachenmaierand Wessmann, 2006; Cassiman and Martínez-Ros, 2007). Furthermore, the influence of R&D on productivity is also widely analyzed. Many studies show that R&D and innovation are important sources of productivity differences between firms, identifying a positive relationship between R&D and productivity and firm growth (Griffith et al., 2006). These productivity gains in firms that invest in R&D will then be reflected in their self-selection into the exporting process, i.e., the more productive firms are more likely to become exporters.

There is already a wide range of empirical literature that examines the relationship between exports and innovation, more specifically, R&D activities, although for the most part these studies explain only one of these variables based on the other (e.g., Wakelin, 1998; Bleaney and Wakelin, 2002; Roper and Love, 2002; Caldera, 2010; Cassiman, Golovko, and Martínez-Ros, 2010; Cassiman and Golovko, 2011; Harris and Li, 2011). However, recently, exports and R&D have been understood as complementary and interdependent (Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013). According to some authors (e.g., Golovko and Valentini, 2011), this complementarity explains the higher levels of performance (sales growth) of Spanish small and medium-sized manufacturing firms (SMEs). However, there is no consensus that there is a complementarity between both strategies, R&D and exports, which in previous studies emerged as alternatives that should not be carried out jointly (Golovko and Valentini, 2011). Indeed, Roper and Love (2002) suggest that in the case of German manufacturing plants where levels of innovation intensity are high but the proportion of sales attributable to new products is low, there was a trade-off between investment in innovation and exports, rather than a complementarity, because of the rival use of limited organizational resources (human and financial). Although they find evidence of complementarity between the two activities for Irish firms, Girma, Gorg, and Hanley (2008) fail to find such evidence for British firms, which reinforces the lack of consensus on this issue.

Existing studies in this area focus mainly on more developed countries —Britain, Germany, the Republic of Ireland—, closer to the technological frontier and with solid and internationalized national and regional innovation systems (Bleaney and Wakelin, 2002; Roper and Love, 2002; Girma, Gorg, and Hanley, 2008; Ganotakis and Love, 2011). In smaller and open countries, where exports are one of the key engines of the economy, but innovation performance lags behind the technological frontier, the existence and significance of export-R&D complementarity has not yet been assessed at the microeconomic level.

The paper aims to fill this gap by using a large firm database of all (more than 340 thousand) non-financial corporations located in Portugal over the period 2006-2012. It contributes to the relevant literature by focusing on firms located in a small, open and peripheral country, Portugal, in which exports are the engine of economic growth, despite the noticeable laggardness in innovation, in general, and R&D, in particular. Specifically, the study raises two main questions: 1) Is there any complementarity between investment in R&D and exports at the company level?; and 2) What is the individual and joint impact of exports and R&D investment on the economic performance of companies?

The empirical analysis is carried out using company data from the Central Balance Sheet of the Bank of Portugal. Such data are based on the Simplified Business Information (SBI) which corresponds to a deposit account that each nonfinancial company has to submit annually to the Ministry of Justice.

To answer the two research questions, and in line with similar studies (e.g., Girma, Gorg, and Hanley, 2008; Golovko and Valentini, 2011; Esteve-Peréz and Rodríguez, 2013), econometric techniques have been employed. Regarding the first question —the complementarity between investment in R&D and exports— we estimate a bivariate probit model. Regarding the second question —the joint impact of exports and R&D investment on the economic performance of companies— we follow the methodology developed by Golovko and Valentini (2011), which encompasses a fixed-effects panel model with AR(1).

The paper is organized as follows. The next section presents a review of the existing literature on the relevant subjects, the relationship between exports and investment in R&D and the impact of R&D and exports on the performance of companies. Section 3 briefly details the methodology. Section 4 presents the results, and Section 5 the conclusions.

A CRITICAL REVIEW OF LITERATUREThe relationship between exports and investment in R&DThe relation between exports and investment in R&D encompasses three major issues: whether innovation (R&D) leads a company to export; whether export activity leads the company to be more innovative; and whether the causal relationship is bidirectional and there is complementarity between the two activities.

There is already fairly extensive research on these issues. Earlier studies treat the first two questions: whether innovation (R&D) leads a company to export and whether export activity leads the company to be more innovative (Wakelin, 1998; Bleaney and Wakelin, 2002; Roper and Love, 2002; Caldera, 2010; Cassiman, Golovko, and Martínez-Ros, 2010; Cassiman and Golovko, 2011; Harris and Li, 2011). Only the more recent studies have tested the third question, i.e., a bidirectional relationship of mutual causality: implicit complementarity and interdependence (Girma, Gorg, and Hanley, 2008; Damijan, Kostevc, and Polanec, 2010; Golovko and Valentini, 2011; Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013). However, there is no consensus in these studies; there are cases of positive evidence of causality (e.g., Girma, Gorg, and Hanley, 2008) for Irish companies; Caldera, 2010; Golovko and Valentini, 2011; Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013) but there are also cases in which this causality is not significant (Girma, Gorg, and Hanley (2008) for United Kingdom companies; Damijan, Kostevc, and Polanec, 2010), and even cases where the relationship is negative (e.g., Roper and Love, 2002) in the case of German manufacturing plants.

The influence of R&D in exportsEarly theoretical literature defends a one-way relationship between innovation and exports. Innovation is identified as one of the determinants of exports (Vernon, 1966; Krugman, 1979). The reasoning behind these early models of the product cycle is that product differentiation and/or innovation generates competitive advantages that enable companies to compete in international markets (Girma, Gorg, and Hanley, 2008). The latest generation of neo-technological models also supports this causal link (Greenhalgh, 1990; Greenhalgh and Taylor, 1994). More recently, Grossman and Helpman (1995) modeled a macroeconomic scenario where firms improve the quality of their products (synonymous with innovation). The result is an outward shift in the demand curve of the country's exports. One possible explanation for this result is that the more a country/firm invests in R&D, the more innovative and competitive its products and/or services become and, hence, a competitive advantage emerges, with positive effects on exports (Lachenmaier and Woessmann, 2006; Cassiman and Martínez-Ros, 2007). Aw, Roberts, and Xu (2011) also identified investment in R&D and the adoption of technology as relevant factors in explaining the higher productivity of exporters compared to non-exporters. According to Aw, Roberts, and Xu (2011), investment in R&D affects future productivity endogenously.1 The influence of R&D on productivity has also been widely studied and many studies show that innovation and R&D are important sources of productivity differences between firms, identifying a positive relationship between R&D and productivity and firm growth (Griffith et al., 2006).

The influence of exports on R&DThere is a theoretical body of literature that explains how companies learn to internationalize and specifically explains the influence of exports on innovation. The central idea is that in order to compete in international markets exporters have to invest in new technology, which is often required to meet the needs of a more sophisticated demand (Girma, Gorg, and Hanley, 2008). Exporting companies also have access to sources of knowledge which are not available in the domestic market (Alvarez and Robertson, 2004). These factors imply that exporters improve their knowledge base and thus increase their innovative capacity, being able to create innovations of better quality (Golovko and Valentini, 2011). Thus, the export activity of a business can have a positive influence on its R&D and innovative capacity (Salomon and Shaver, 2005b; Girma, Gorg, and Hanley, 2008).

The abovementioned phenomenon is labeled the ‘learning-by-exporting effect’. This effect is theoretically demonstrated by Hobday (1995) who develops a technology-gap model to show that external demand, and thus export activity, increase the rate of innovation. The author proves that knowledge is cumulative and that its progression leads to a path of growth in companies. The overwhelming conclusion of the model is that exports positively influence the technological and innovative capacity of firms.

The complementarity between exports and R&DThe analysis of the influence of exports on R&D and vice versa raises the question of complementarity and interdependence between the two activities. Aw, Roberts, and Xu (2011) found that decisions to export and invest in R&D or technology are interdependent and both influence the future profitability of firms. According to these authors, these investment decisions depend on the expected return of the sunk costs of entry in these activities. Aw, Roberts, and Xu (2011) argue that, on the one hand, investment in R&D increases productivity, which leads to improved net profits expected from export; and, on the other hand, the global market share can increase the return on investment in R&D. Additionally, Bernard and Jensen (1999) argue that the implementation of one of these activities can reduce the costs of implementing the other. Specifically, innovation can reduce the costs of exporting. According to the authors, exporting entails some sunk costs, first at the beginning of the activity, but also later when it evolves. These sunk costs are packaging costs, improving product quality, establishing marketing channels and the gathering of information on sources of demand (Roberts and Tybout, 1999). Exporting companies also have administrative and additional shipping costs, which generate a disadvantage compared to domestic companies in the market to which they are exporting (Golovko and Valentini, 2011). Consistently, the literature has shown that firms that start to export are more productive than those that do not, because only then are they able to bear the additional costs that exporting implies (Bernard and Jensen, 1999). Specifically, Cassiman and Golovko (2011) show that innovation is the source of higher productivity and self-selection of more productive firms to export. Thus, by improving productivity, innovation reduces the costs associated with exports (Golovko and Valentini, 2011). Moreover, exporting firms have more incentives to invest in R&D, because this investment will be diluted by a larger output (Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013), thus reducing the R&D/ turnover ratio. Also, exports can reduce the costs of R&D via capital markets. Investment in innovation, including R&D, implies the application of large financial resources in the short-term with the expectation of positive returns in the future (Golovko and Valentini, 2011). If capital markets are completely efficient, and if the information is available to all parties, then companies should get external financing for all profitable investment opportunities (Golovko and Valentini, 2011). However, if these conditions are not met, external financing may not be available, or may become too expensive, and hence companies are subject to the internal constraints related to generating financial flows to finance their investments (Golovko and Valentini, 2011). Thus, companies with variable cash flows face significant restraints in making investments in innovation that have a particularly uncertain return (Golovko and Valentini, 2011). According to Salomon and Shaver (2005a), exporting companies can stabilize cash flows, since business cycles are not perfectly correlated between national economies. Thus, exporting companies can have more resources to invest in innovation (Golovko and Valentini, 2011). And they can also have cheaper access to external financing, as exports give more guarantees to markets that companies have liquidity to meet their obligations (Shaver, 2011).

According to the cognitive approach, both strategies are considered key channels for the accumulation of knowledge, improving the firms’ capabilities and their competitive advantages and hence their profitability (Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013). The size of the generation and accumulation of knowledge in R&D is well known since the seminal paper by Cohen and Levintal (1989). For exports, the cognitive dimension was recognized only more recently and is less consensual (Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013). According to Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez (2013), participation in international markets generates knowledge flows through three channels: 1) interaction with foreign competitors; 2) increase in the scale of production; and 3) increased competition raises incentives for innovation. The complementarity between the two activities in terms of knowledge accumulation exists for two reasons. First, the internal knowledge generated by R&D activities helps to build technological capabilities which enable the absorption of external knowledge acquired in the export market, thus generating a higher return from exports for companies that have accumulated knowledge through internal R&D (Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013). Second, experience in exports generates knowledge flows that increase the innovative capacity of firms and their R&D activities (Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013). These knowledge flows are derived from contact with the richest sources of technology, with the best international practices and with tougher competitors (Girma, Gorg, and Hanley, 2008; Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013).

Thus, according to the literature, and despite the lack of consensus among the empirical studies, it is expected that there be some degree of complementarity between investment in R&D and exports at the company level.

The impact of R&D and export on the performance of companiesThe literature review conducted in previous sections suggests that R&D and exports should be complementary in assessing their impact on economic performance. The two activities complement each other in terms of accumulation of knowledge, lowering costs and boosting the firms’ profits. R&D, through its impact on productivity and on new and better products; and exports, directly amplifying the positive effect of R&D. Confirming this reasoning, Golovko and Valentini (2011) show that the positive effect of innovation on firm growth is higher if firms export and vice versa. Filatotchev and Piesse (2009) also examine the interrelationship between R&D, exporting and sales growth of newly listed firms in the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy and France, and they find that both R&D and export intensities have a positive effect on sales growth.

The isolated impact of exports and R&D investment on the performance of companiesApart from the clear and obvious effect of exports on sales (Shrader, Oviatt, and McDougall, 2000), their positive effect on the growth of companies is due to the indirect gains obtained from revenue diversification (e.g., Shaver, 2011) and the development of new capabilities promoted by internationalization, which increase the ability of the company to pursue new growth opportunities (e.g., Sapienza et al., 2006).

Innovation in general and R&D in particular can have several positive impacts on the performance of companies. Innovation can create new product markets or increase the willingness of consumers to pay for new or improved product features (e.g., Cho and Pucik, 2005). Also, innovative companies are better prepared to take advantage of spillovers and are more resistant to macroeconomic shocks (Geroski, Machin, and Van Reenen, 1993).

Impact of R&D investment and export complementarity on the performance of companiesThe analysis in the previous sections suggests a positive interdependence between exports and investment in R&D. The contribution of exports to sales growth depends on the amount that can be exported and on the price at which firms can sell in international markets (Golovko and Valentini, 2011). There is strong evidence that the “law of one price” —i.e., the same products are sold at the same price in different countries— does not hold (Golovko and Valentini, 2011). Moreover, it is clear that the deviation in the law of one price is not an artifact of non-identical goods (Goldberg and Knetter, 1997). More specifically, foreign markets often generate lower mark-ups compared to the domestic market (e.g., Bughin, 1996). Competition and the costs related to exports are among the drivers of the lower mark-ups observed (Golovko and Valentini, 2011).

Most differences between the domestic price and the export price are due to price differences between companies in the same market. Differences between markets are relatively less important (Golovko and Valentini, 2011). These variations within the same market reflect differences in the attributes and quality of the products (Aw, Chen and Roberts, 2001) explained by investment in innovation (Golovko and Valentini, 2011). More specifically, Braymen, Briggs, and Boulware (2011), analyzing newly founded North-American companies, demonstrate how investment in R&D enables companies to produce better varieties of products that have global demand. McGuinness and Little (1981) also conclude that improvement of the products’ unique features and the differentiation of existing products increase export performance and sales growth. Moreover, investing in innovation for exports can also bring positive spillovers to the domestic market (Golovko and Valentini, 2011). Specifically, producers exporting a particular variety of a product can achieve a premium price for sales of the same variety in the domestic market, which is associated with an increase in investment activity when the new variety is released (Iacovone and Javorcik, 2012).

Thus, it is expected that the complementarity between exports and R&D impacts on sales growth because the innovative exporting companies can increase their sales by selling the best products on export markets (managing to sell a larger quantity or getting a more favorable price) while price can also benefit from positive spillovers of sales in the domestic market that will be of better quality (Golovko and Valentini, 2011).

As already mentioned in the previous section, there is also a complementarity between R&D and exports regarding the accumulation of knowledge. The greater the complementarity, and the greater the knowledge accumulated by companies and their ability to learn, the greater the benefit to companies undertaking both activities simultaneously. Logically, complementarity in terms of costs leads companies to be more competitive and thus to achieve higher sales growth both internally and externally.

Based on the above arguments, it is expected that, apart from a positive impact of R&D and exports on sales growth individually considered, there will be an additional positive impact related to the complementarity of R&D and exports.

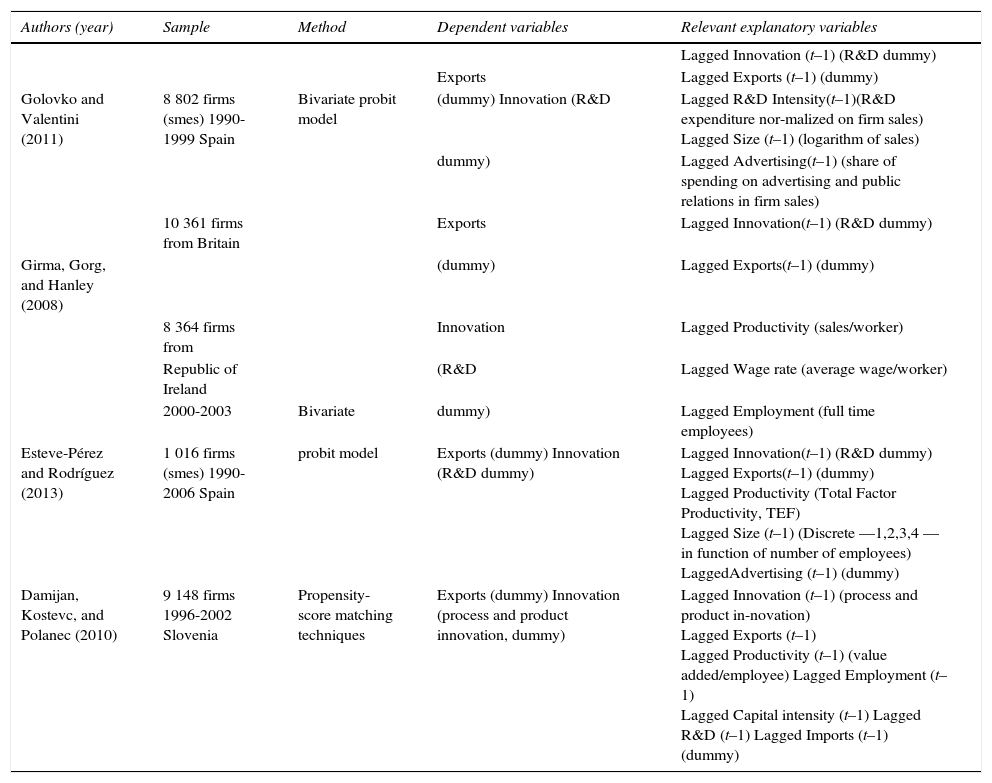

METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONSBrief overview of the literature on the relevant methodologies and proxiesTo answer the first research question about the interdependence between investment in R&D and exports, and similarly to Aw, Roberts, and Winston (2007), Girma, Gorg, and Hanley (2008), Golovko and Valentini (2011) and Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez (2013) (see Table 1), we have developed a bivariate probit model. This method explicitly takes into account a possible correlation between export and R&D activities (Golovko and Valentini, 2011; Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013).

Methodology of studies on complementarity between investment in R&D and exports.

| Authors (year) | Sample | Method | Dependent variables | Relevant explanatory variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lagged Innovation (t–1) (R&D dummy) | ||||

| Exports | Lagged Exports (t–1) (dummy) | |||

| Golovko and Valentini (2011) | 8 802 firms (smes) 1990-1999 Spain | Bivariate probit model | (dummy) Innovation (R&D | Lagged R&D Intensity(t–1)(R&D expenditure nor-malized on firm sales) Lagged Size (t–1) (logarithm of sales) |

| dummy) | Lagged Advertising(t–1) (share of spending on advertising and public relations in firm sales) | |||

| 10 361 firms from Britain | Exports | Lagged Innovation(t–1) (R&D dummy) | ||

| Girma, Gorg, and Hanley (2008) | (dummy) | Lagged Exports(t–1) (dummy) | ||

| 8 364 firms from | Innovation | Lagged Productivity (sales/worker) | ||

| Republic of Ireland | (R&D | Lagged Wage rate (average wage/worker) | ||

| 2000-2003 | Bivariate | dummy) | Lagged Employment (full time employees) | |

| Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez (2013) | 1 016 firms (smes) 1990-2006 Spain | probit model | Exports (dummy) Innovation (R&D dummy) | Lagged Innovation(t–1) (R&D dummy) Lagged Exports(t–1) (dummy) Lagged Productivity (Total Factor Productivity, TEF) Lagged Size (t–1) (Discrete —1,2,3,4 — in function of number of employees) LaggedAdvertising (t–1) (dummy) |

| Damijan, Kostevc, and Polanec (2010) | 9 148 firms 1996-2002 Slovenia | Propensity-score matching techniques | Exports (dummy) Innovation (process and product innovation, dummy) | Lagged Innovation (t–1) (process and product in-novation) Lagged Exports (t–1) Lagged Productivity (t–1) (value added/employee) Lagged Employment (t–1) Lagged Capital intensity (t–1) Lagged R&D (t–1) Lagged Imports (t–1) (dummy) |

To test whether the complementarity between exports and R&D investment impacts on the economic performance of firms (i.e., sales growth), we follow Golovko and Valentini's (2011) methodology. A growth regression is estimated using a fixed-effects model in order to account for the possible endogeneity of export and innovation decisions, and the measure of performance in this model —such a method serves to control for time-invariant, unobserved firm heterogeneity (Golovko and Valentini, 2011). Furthermore, a First-Order Autoregressive (AR(1)) process for the errors is used in order to control for the presence of the serial correlation in the model (Golovko and Valentini, 2011).

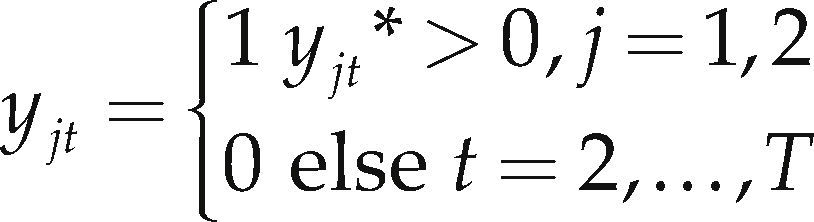

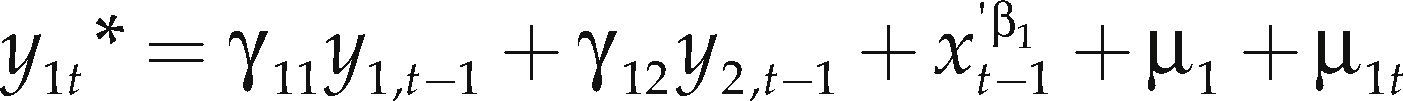

Econometric specification for testing the complementarity between exports and R&DAs previously discussed, to test the complementarity between exports and R&D expenditures a bivariate probit model will be applied. This model takes into account the possible correlation between the error terms in each of the model's equations that may arise given the high degree of serial correlation and the interdependence between exports and R&D (Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013). Following Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez (2013), the specification of the bivariate model is (for simplification, the firm's indexes are suppressed):

The dependent variables are binary variables associated with exports (y1t) and R&D expenditures (y2t). y1t is a binary variable equal to 1 if the firm is an exporter in the current year, and 0 if it is not. y2t is a binary variable equal to 1 if the firm has any positive R&D expenditure in t, and 0 if it does not (Girma, Gorg, and Hanley, 2008). Following Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez (2013), the same independent variables will be used in the two equations, including initial conditions and within-individual means. It is assumed that (μ1,μ2) is distributed as a bivariate normal with variances σμ12 and σμ22 and covariance σμ1 σμ2 ρμ(Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013). It is also assumed that error terms (μ1t,μ2t) are bivariate standard normal with covariance ρ and are independent over time. Finally, it is assumed that (μ1,μ2), ujt and xt–2 are independent (Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013).

The output of this model is the probability of exporting and of investing in R&D in year t, based on the characteristics of laggard firms (Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013). The lagged value of R&D is the key variable in the exports equation and the lagged value of exports is the key variable in the R&D equation, because the relationship between exports and R&D is the central research question. The presence of the lagged R&D variable in the exports equation aims to test whether engaging in R&D will increase the firms’ exports and whether engaging in exports will increase their R&D (Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013).

Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez (2013) argue that, within the cognitive approach, these lagged variables are proxies for the stock of knowledge (internally accumulated —R&D; externally accumulated —exports). The lagged exports in the R&D equation also test the so-called learning-by-exporting effect (that captures the potentially positive impact of previous export activity on new R&D expenditure as explained in Girma, Gorg, and Hanley (2008). In order to test the persistence and cross-persistence of exports and R&D, we include lagged variables for both in each equation (Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013). The inclusion of the exports variable also accounts for the importance of sunk costs in the internationalization process (Girma, Gorg, and Hanley, 2008).

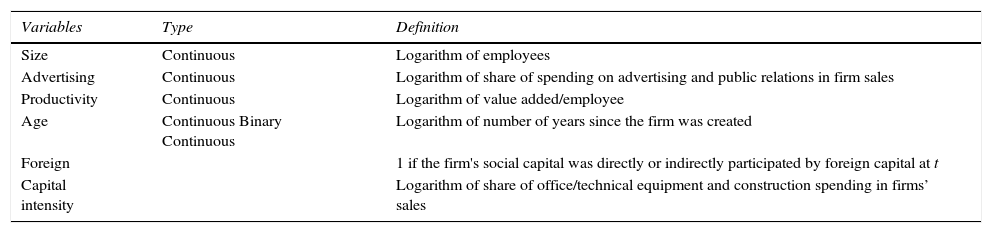

In line with previous studies employing a similar model (Aw, Roberts, and Winston, 2007; Girma, Gorg, and Hanley, 2008; Golovko and Valentini, 2011; Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013), a set of additional explanatory variables is included in the x-vector as control variables, presented in Table 2.

Additional explanatory variables.

| Variables | Type | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Size | Continuous | Logarithm of employees |

| Advertising | Continuous | Logarithm of share of spending on advertising and public relations in firm sales |

| Productivity | Continuous | Logarithm of value added/employee |

| Age | Continuous Binary Continuous | Logarithm of number of years since the firm was created |

| Foreign | 1 if the firm's social capital was directly or indirectly participated by foreign capital at t | |

| Capital intensity | Logarithm of share of office/technical equipment and construction spending in firms’ sales |

The lagged productivity is included as a proxy of the firms’ efficiency in line with existing studies and to take account of the self-selection of more efficient firms regarding their export activity (Aw, Roberts, and Winston, 2007; Silva, Afonso, and Africano, 2013). The expected relationship between the previous productivity level and returns from both R&D and exports is positive (Aw, Roberts, and Xu, 2011).

Firm size is an important control variable that may affect both exports and R&D decisions (Golovko and Valentini, 2011). The expected relationship between firm size and exports and between firm size and R&D is positive (Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013). However, there are some authors, such as Bernard and Jensen (1999), who find a non-linear relationship between size and exporting, showing that the positive effect of size only emerges after a certain threshold. On average, larger firms have access to more resources to invest in R&D (Golovko and Valentini, 2011). These resources, necessary to carry out investment decisions that involve uncertainty and sunk costs, are more accessible to larger firms because they are more likely to obtain loans as well as non-financial resources (managerial, scale economies) (Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013). Nevertheless, small firms may have an advantage, especially in innovative activities, because they are more flexible in adapting to changing competitive environments, and can have more flexible management structures (Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013). Small firms are also associated with less bureaucracy and, thus, may positively influence efficiency in innovating (Acs and Audretsch, 1987).

Foreign participation in the firms’ capital is included because it can facilitate the process of becoming an exporter (Basile, 2001). In addition, foreign-owned firms may have better access to financial resources, knowledge and technology (Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013). Thus, a positive effect of foreign participation in export activities is expected. The effect of this participation in R&D investment is unclear because innovative activities may take place in the parent firm or the firm may take advantage of the stock of knowledge and financial resources of the parent firm to carry out its own R&D activities (Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013).

Advertising expenditures are included due to their expectable positive effect on exports. In fact, advertising helps to build up brands or trade names (Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013).

Capital intensity is included with advertising intensity as proxies for complementary assets (Teece, 1986). These complementary assets include firm capabilities like manufacturing or sales expertise (Golovko and Valentini, 2011). The presence of complementary assets has an expected positive impact both on exports and innovation activities, since these capabilities are used to bring new product/process innovations to the market (Golovko and Valentini, 2011).

Age has an unclear effect both on exports and R&D. On the one hand, older firms are more likely to have the required resources (financial and knowledge) to implement these activities; on the other hand, if younger firms are more flexible, aggressive and proactive, a negative relationship could be expected (Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013).

In addition, sections of the Nomenclature statistique des Activités économiques dans la Communauté Européenne (nace) and year dummies are included to control for industry heterogeneity and macroeconomic conditions common to all firms (Golovko and Valentini, 2011).

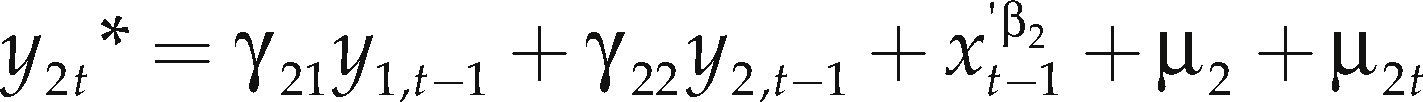

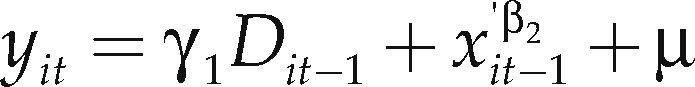

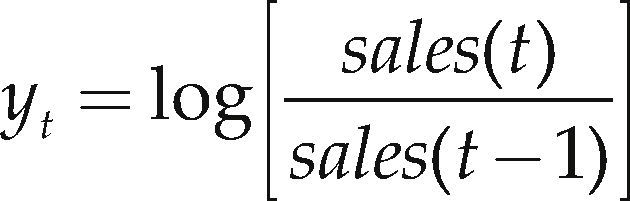

Econometric specification and proxies for testing the individual and complementary impact of exports and R&D on the performance of companiesThe other central research question of this study is to measure the individual and the complementary impact of exports and R&D on the performance of companies, more precisely on sales growth. The choice of sales growth to measure performance is in line with previous studies, consensually used in data that contain firms from different industries (e.g., Golovko and Valentini, 2011), which is the case in this study.

To test whether the complementarity between exports and R&D investment impacts on the economic performance of firms, the following growth regression is estimated (in line with Golovko and Valentini, 2011). The model includes four exclusive dummies for exporting/R&D activities that will be estimated in order to link them to firm growth (Golovko and Valentini, 2011):

The dependent variable is firm i's sales growth rate at time t (with respect to time t–1). Following Golovko and Valentini (2011), an exponential sales growth trend will be considered:

In this model, the simple export and R&D dummies are excluded and a vector of exclusive dummy variables D for the choice of the combination of the export and R&D activities in year t–1 is used (Golovko and Valentini, 2011):

When R&D and exports are complementary, the estimation of the parameter associated with the variable Export and R&D is positive and statistically significant. We include as control variables the explanatory variables used in the bivariate probit model plus wage rate, measured as the logarithm of average wage/employee, to test if the complementarity between R&D and exports has an effect on the growth rate: size to account for the link between firm size and growth (Lu and Beamish, 2006); foreign as potentially responsible for differences in growth and in exports between domestic and foreign firms (Golovko and Valentini, 2011), and wage rate as a proxy for the employees’ skill intensity (Bleaney and Wakelin, 2002).

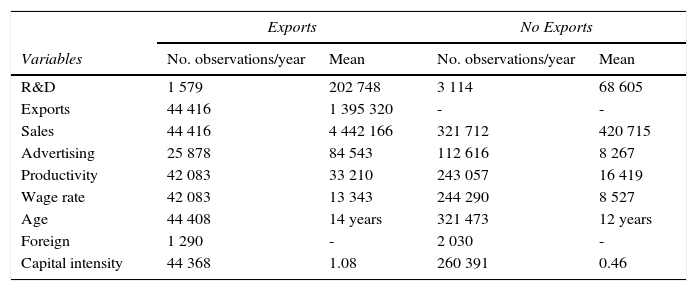

DATA DESCRIPTIONThe data used in this study are taken from the Central Balance Sheet of the Bank of Portugal that covers the universe of non-financial corporations in Portugal over the period 2006-2012.

Such data are based on the SBI which corresponds to a deposit account that each non-financial company has to submit annually to the Ministry of Justice. These data also are used by the Bank of Portugal and the National Institute of Statistics for statistical purposes and the Ministry of Finances for fiscal purposes. This report provides exhaustive, standard accounting information at the firm level.

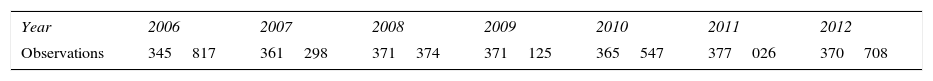

A problem with the data is that a change was introduced in the Portuguese accounting system in 2010. For most of the data we require to support our study this change is not a problem; however, regarding the data on innovative activities, it could mean a break in the series. The main problem resides in the fact that in the first accounting system the data on R&D includes software expenditures and, beyond problems related to non-responses, it is rather difficult to exclude those values from R&D expenditures. This causes problems of comparability between the data in the two parts of the series. In the first part, as we can see in Table 4,2 there are more firms with R&D expenditures but with smaller values and, in the second part, there are only a few firms with R&D but with higher values. The series of exports is consistent in terms of the number of firms exporting and the values of exports in both periods. The other series of variables are also consistent in both periods.

Descriptive statistics.

| 2006-2009 | 2010-2012 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | No. observations/year | Mean | No. observations/year | Mean |

| R&D | 6 181 | 51 590 | 2 709 | 200 696 |

| Exports | 41 527 | 1 413 857 | 48 274 | 1 370 405 |

| Sales | 362 557 | 925 966 | 371 173 | 879 532 |

| Advertising | 146 460 | 23 300 | 127 872 | 21 425 |

| Productivity | 280 078 | 19 666 | 291 887 | 17 894 |

| Wage rate | 280 078 | 9 275 | 294 765 | 9 186 |

| Age | 362 521 | 11 years | 370 643 | 12 years |

| Foreign | 3 273 | - | 3 384 | - |

| Capital intensity | 305 407 | 0.96 | 303 893 | 1.02 |

Source: Authors’ computations based on the Bank of Portugal's SBI

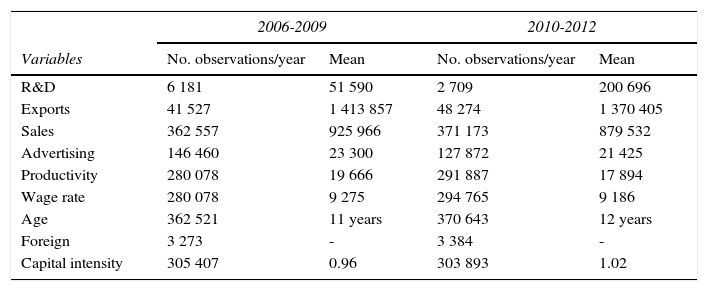

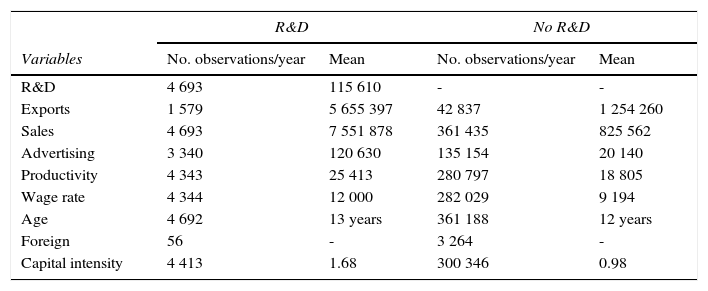

Table 5 shows the difference regarding main descriptive statistics between firms that have R&D expenditures and those that do not. Table 6 describes this difference for firms that export and firms that do not. On average, firms with both R&D and exports have more sales, are older, have higher advertising investments and higher capital intensity, are more productive, and offer higher wages, i.e., are endowed with better human capital. In terms of foreign capital, the firms that have R&D expenditures also have, on average, higher weights than the other group; however, this difference is very small (1.27% vs. 1%). In the case of firms with exports, the difference is considerably higher (2.97% vs. 0.72%). Finally, in relation to our key variables, Table 5 illustrates that firms with R&D expenditures have a much higher percentage of exports than firms without R&D (33.65% vs. 11.85%). Table 6 shows a similar conclusion since firms with exporting activities have a relatively higher percentage of R&D expenditures (3.56% vs. 0.97%).

Descriptive statistics firms with R&D vs. firms without R&D.

| R&D | No R&D | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | No. observations/year | Mean | No. observations/year | Mean |

| R&D | 4 693 | 115 610 | - | - |

| Exports | 1 579 | 5 655 397 | 42 837 | 1 254 260 |

| Sales | 4 693 | 7 551 878 | 361 435 | 825 562 |

| Advertising | 3 340 | 120 630 | 135 154 | 20 140 |

| Productivity | 4 343 | 25 413 | 280 797 | 18 805 |

| Wage rate | 4 344 | 12 000 | 282 029 | 9 194 |

| Age | 4 692 | 13 years | 361 188 | 12 years |

| Foreign | 56 | - | 3 264 | - |

| Capital intensity | 4 413 | 1.68 | 300 346 | 0.98 |

Source: Authors’ computations based on the Bank of Portugal's SBI

Descriptive statistics firms with exports vs. firms without exports.

| Exports | No Exports | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | No. observations/year | Mean | No. observations/year | Mean |

| R&D | 1 579 | 202 748 | 3 114 | 68 605 |

| Exports | 44 416 | 1 395 320 | - | - |

| Sales | 44 416 | 4 442 166 | 321 712 | 420 715 |

| Advertising | 25 878 | 84 543 | 112 616 | 8 267 |

| Productivity | 42 083 | 33 210 | 243 057 | 16 419 |

| Wage rate | 42 083 | 13 343 | 244 290 | 8 527 |

| Age | 44 408 | 14 years | 321 473 | 12 years |

| Foreign | 1 290 | - | 2 030 | - |

| Capital intensity | 44 368 | 1.08 | 260 391 | 0.46 |

Source: Authors’ computations based on the Bank of Portugal's sbi.

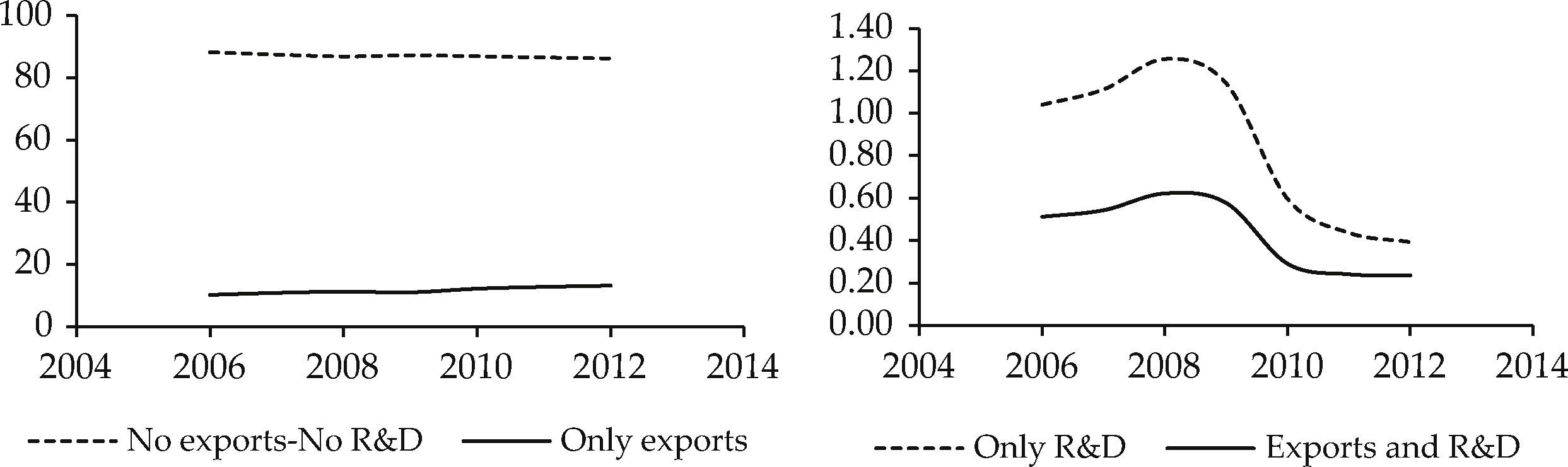

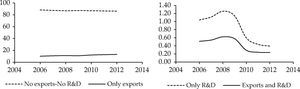

Figure 1 shows the evolution of the firms’ participation in export and R&D activities over the period in study. Firms are categorized in the following manner: no participation in both exports and R&D; participation in export activities, participation in R&D activities, and participation in both.

In the first part of the dataset, the percentages of firms that engage in R&D, in exports and in both activities have a somewhat similar evolution, with an increase in the respective weights between 2006 and 2009. The decrease in 2010 may have been caused by the international crisis. In the second part of the dataset, with the new accounting system, the percentage of firms with R&D activities is smaller and follows a negative trend, whereas the percentage of firms with just export activities increases up to 13.44% in 2012.

In this figure, we cannot see a positive relationship between exporting and R&D activities. However, this figure does not show the individual dynamics of the firms and we do not know whether it is the same group of firms that have made R&D investments and/or compete in export markets. Hence, Table 5 intends to show the joint dynamics of these two investment decisions and highlights whether they are the same firms or whether a large percentage of new firms is involved in these activities.

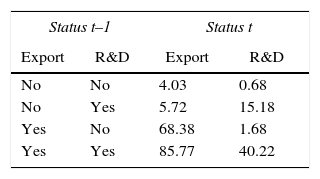

Table 7 provides preliminary evidence on the dynamics of the two-way relationship between export and R&D activities. This information is about yearto-year transition probabilities over the period 2006-2012. The two main points of this analysis are: firstly, these activities are persistent, in particular, the export activity is highly persistent. The probability of being an exporter in t is more than 72 percentage points higher for exporters than for non-exporters at t–1. More specifically, it is 64% (68.38-4.03) for non-R&D performers and 85% (85.77-5.72) for R&D performers. For R&D activity, the persistence is not as high but does still exist. Firms that engaged in R&D at t–1 are more likely (26 percentage points (p.p.)) to also undertake R&D at t, compared to those that do not engaged in R&D; secondly, there is cross-persistence between R&D and export activity, i.e., the probability of engaging in R&D at t is larger for exporters at t–1 than for non-exporters (18 p.p.) and vice versa (10 p.p.). So, we have preliminary evidence that there is cross-dependence between export and R&D activities and also that past decisions influence current investment decisions.

EMPIRICAL RESULTSThe relationship between exports and R&DIn the previous section, we found preliminary evidence of cross-dependence and high persistence in both exports and R&D. In this section, we undertake econometric analyses that examine the two-way dynamic relationship between exports and R&D activities. Following the previous methodological procedures, a bivariate probit model is developed in order to examine the sources of the two-way dynamic relationship. This specification enables the joint estimation of the two decisions taking into account the correlation between the error terms in the export and R&D equations (Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013).

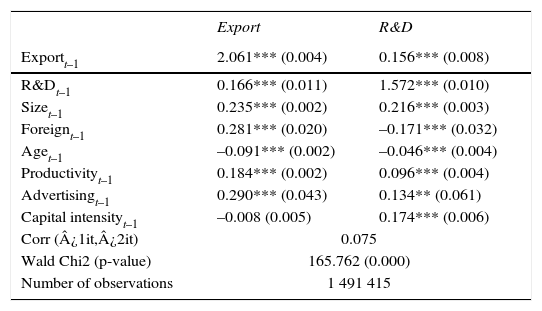

Table 8 presents the estimated coefficients using standard errors robust to intra-group (firms) correlation. This model includes as explanatory variables the lagged values of R&D, exports, foreign ownership, age, productivity, advertising, capital intensity and firm size. A set of sector and year dummy variables are also included, which are always jointly significant, though their estimated coefficients are not reported. Except for variable capital intensity in the export equation, all the variables have a significant effect on the export and R&D decisions at the 1% level of statistical significance.

Exports and R&D: bivariate probit estimation.

| Export | R&D | |

|---|---|---|

| Exportt–1 | 2.061*** (0.004) | 0.156*** (0.008) |

| R&Dt–1 | 0.166*** (0.011) | 1.572*** (0.010) |

| Sizet–1 | 0.235*** (0.002) | 0.216*** (0.003) |

| Foreignt–1 | 0.281*** (0.020) | –0.171*** (0.032) |

| Aget–1 | –0.091*** (0.002) | –0.046*** (0.004) |

| Productivityt–1 | 0.184*** (0.002) | 0.096*** (0.004) |

| Advertisingt–1 | 0.290*** (0.043) | 0.134** (0.061) |

| Capital intensityt–1 | –0.008 (0.005) | 0.174*** (0.006) |

| Corr (¿1it,¿2it) | 0.075 | |

| Wald Chi2 (p-value) | 165.762 (0.000) | |

| Number of observations | 1 491 415 | |

Note: ***, ** and * indicate statistical significance at 1, 5 and 10% levels, respectively. The model includes 18 sector dummies variables. Source: Authors’ computations based on the Bank of Portugal's sbi

The results of the export equation indicate that, conditional on average values of the remaining variables, firms engaged in R&D at t–1 have a 16.6% higher probability of exporting at t than those not engaged in R&D in the previous period. The results for the R&D equation also indicate that past exporting has a positive and significant effect on the probability of undertaking R&D at t, and that this effect is almost the same (15.6%). These results confirm the cross-persistence between exports and R&D and emphasize that the performance of one activity positively and significantly relates to the performance of the other. This means that the answer to the first question of our study —whether there is a complementarity between export and innovation— is positive.

As expected, in both equations, the lagged dependent variables (export and R&D) are positive and highly significant, which means that past engagement in exports is associated with a higher probability of current engagement in exports and also that past engagement in R&D increases the probability of current engagement in R&D.

The estimated effect of our control variables obtains the expected effect in most of the cases. The size of the firm has a positive and significant effect on both decisions, to innovate and to export, which means that larger firms, in terms of employees, tend to present a higher probability to export and perform R&D in the next period. The effect of foreign ownership is positively and significantly related to the decision to export, which means that the fact of having a foreign owner at t–1 increases the probability of exporting at t. However, it has a negative effect on the decision to engage in R&D, meaning that nationally-owned companies tend to be more prone to perform R&D activities. Age has a negative effect on both decisions. This result reflects that younger firms are more likely to export and perform R&D than their older counterparts, which conveys good news for the renewal of Portuguese businesses. Productivity has a positive effect on both exports and R&D, with the coefficient associated with exports being approximately twice that of R&D, which means that more productive firms have higher probabilities of exporting and engaging in R&D; however these probabilities increase more in export activities. This positive and significant effect of productivity on exports corroborates the self-selection argument that the most efficient firms self-select into export activity, being in line with results from previous literature (e.g., Aw, Roberts, and Winston, 2007; Silva, Afonso, and Africano, 2013). The impact of advertising is positive on both activities, presenting also a larger coefficient in exports (more than twice than that of R&D), which means that firms that invest heavily in advertising enhance the probability of engaging in exports and also in R&D, with the probability of exports increasing more. Finally, capital intensity fails to emerge as statistically significant in the export equation but presents an expected positive effect on R&D. This means that for firms in Portugal, past capital intensity does not directly influence the probability of exporting in the next period, but it does influence the probability of engaging in R&D activities. Given that R&D has a positive influence on the probability of exporting then, indirectly, capital intensity also impacts on the probability of exporting, though that impact may only emerge over the mid-term rather than in the short-term.

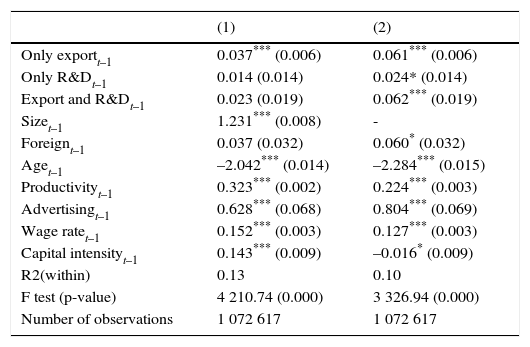

The impact of exports and R&D on firm performanceTo answer to the second research question —what is the individual and joint impact of exports and R&D investment on the economic performance of companies? —, we develop a model that includes four exclusive dummies for exporting/R&D activities in order to link them to firm growth. Specifically, two specifications are employed, one with size as a control variable and the other without size (cf. Table 9) because the number of firms that simultaneously perform R&D and export is very small, and are in general larger firms. In these specifications, the lagged choices of R&D and exports distinguish three cases: firms that both exported and innovated (Export and R&D), firms that only exported (Only export), and firms that only performed R&D (Only R&D). The omitted or base case is a firm that does not engage in any of these activities. The Hausman test indicates that fixed effects with AR(1) is the most adequate specification, which is in line with prior works (e.g., Golovko and Valentini, 2011).

Performance of exports and R&D: AR(1) panel model with fixed effects.

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Only exportt–1 | 0.037*** (0.006) | 0.061*** (0.006) |

| Only R&Dt–1 | 0.014 (0.014) | 0.024* (0.014) |

| Export and R&Dt–1 | 0.023 (0.019) | 0.062*** (0.019) |

| Sizet–1 | 1.231*** (0.008) | - |

| Foreignt–1 | 0.037 (0.032) | 0.060* (0.032) |

| Aget–1 | –2.042*** (0.014) | –2.284*** (0.015) |

| Productivityt–1 | 0.323*** (0.002) | 0.224*** (0.003) |

| Advertisingt–1 | 0.628*** (0.068) | 0.804*** (0.069) |

| Wage ratet–1 | 0.152*** (0.003) | 0.127*** (0.003) |

| Capital intensityt–1 | 0.143*** (0.009) | –0.016* (0.009) |

| R2(within) | 0.13 | 0.10 |

| F test (p-value) | 4 210.74 (0.000) | 3 326.94 (0.000) |

| Number of observations | 1 072 617 | 1 072 617 |

Note: ***, ** and * indicate statistical significance at 1, 5 and 10% levels, respectively. Models include 18 sector dummies. Source: Authors’ computations based on the Bank of Portugal's sbi.

Table 9 presents the two specifications with and without size as the control variable. In the model (1) with size, only the dummy Only exports has a positive and significant effect on growth, whereas the other two main variables of our study are not significant. This means that exporters at t–1 have higher sales growth at t. However, companies engaged in R&D emerge with no significant impact on sales growth in the following period. Similarly, firms with both exports and R&D also do not have a statistically significant impact on sales.

In this specification, the control variables have the expected signs and significance. Size, productivity, advertising, wage rate and capital intensity have a positive and significant effect on growth, reflecting that, all else remaining constant, on average, a large, more productive firm, with high advertising expenditures, better wages and more capital-intensive, tends to be more dynamic in terms of sales. In contrast, foreign ownership does not emerge as statistically significant, whereas age presents a negative effect, meaning that younger firms have higher growth in terms of sales. In model (2) without size, the three dummies of our main variables (Only exports, Only R&D, Export and R&D) are positive and significant, which means that compared to the firms that do not export nor are involved in R&D activities, companies that only export or only perform R&D activities or engage in the two activities simultaneously achieve a better performance in terms of sales. Those that simultaneously export and perform R&D activities have, on average, a stronger impact in terms of sales growth, reinforcing the result obtained previously regarding Export and R&D complementarity.

The above results reveal that exporting per se and coupling exports with R&D activities have a positive and highly significant impact on the firms’ sales growth. Thus, the answer to our second question (What is the individual and joint impact of exports and R&D investment on the economic performance of companies?) is clear-cut: joint exporting and R&D produces the highest impact on firm growth, followed by ‘only export’ and then Only R&D. It is important to note that although R&D per se conveys the weakest direct impact on firm growth, it indirectly impacts on the latter via exports —indeed, as we noted in the previous subsection, R&D increases the likelihood of firms to export in the next period (cf. Table 8), which then has a direct and positive effect on sales growth (cf. Table 9).

CONCLUSIONSThis study uses firm-level data from Portugal to analyze the two-way dynamic relationship between R&D and exporting activities and to explore the effect of R&D and exports on the sales growth of firms. Our null hypotheses are that R&D and exports are complementary activities that reinforce each other, and which have a higher positive effect on sales growth if the two activities are in place simultaneously.

Based on more than 340 thousands firms over the time span 2006-2012, the results indicate that there is a strong cross-dependence in the firms’ decisions to export and engage in R&D. Thus, engaging in export activities increases the firms’ chances of engaging in R&D and engaging in R&D activities increases the firms’ chances of engaging in exports, which in turn increases the firms’ chances of succeeding in the other activity again. Such results suggest that there are complementarities between exports and R&D, a result in line with recent works in the field, most notably those by Ito and Lechevalier (2010), Golovko and Valentini (2011), and Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez (2013).

These results are also consistent with the predictions of the theoretical frameworks described in Section 3. The findings provide support for the hypothesis that more productive firms self-select into exporting activities and also provide support for the learning-by-exporting hypothesis, which argues that previous export participation enhances investment in R&D due to the fact that a larger export market provides higher returns to R&D.

Finally, the findings are also consistent with the cognitive approach that considers exporting and R&D activities as potential and complementary channels for knowledge acquisition (Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013). These results are fairly robust given that the bivariate probit model takes into account the correlation between error terms in the two participation equations (Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013).

Also, the hypothesis of complementarity between the two activities in terms of impact on sales growth is corroborated in our study and this result is in line with previews works, namely Filatotchev and Piesse (2009) and Golovko and Valentini (2011). The hypothesis of complementarity between the two activities (exports and R&D) in terms of impact on sales growth means that compared to firms that do not export nor are involved in R&D activities, companies that export and engage in R&D have a better performance in terms of sales. This conclusion reinforces the result obtained previously regarding Export and R&D complementarity.

Although the results obtained are robust —the methodology undertaken, fixed effects with AR(1), and the large sample used, encompassing more than 1 million observations— it is important to highlight some pitfalls or limitations. First, and as Golovko and Valentini (2011) argue, the exclusive use of dummy variables to describe R&D and export activities has the worthy property of not imposing any specific functional form on the growth regression, more fine-grained data on R&D and exports (e.g., export and R&D intensity) could be profitably exploited. Second, due to unavailability of data, we did not control for where the export activity is directed at, assuming that exporting may be equally beneficial regardless of the export market. Salomon (2006) shows that there are important benefits, in terms of incoming knowledge spillovers, when exporting to developed foreign markets. Thus, firms that export to more developed markets would present a stronger complementarity relationship between exports and R&D (Golovko and Valentini, 2011). Third, we work with data from one single country. In this vein, we cannot assess the effect of differences in institutional, financial and governance regimes and test whether these factors could matter for the link between the firms’ strategic choices and growth (Sapienza et al., 2006).

Despite the limitations, our results are in line with previous studies for other countries such as Spain (e.g., Golovko and Valentini, 2011, and Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez, 2013), Taiwan (Aw, Roberts, and Xu, 2011), Ireland (Girma, Gorg, and Hanley, 2008), and (partially) for Slovenia (Damijan, Kostevc, and Polanec, 2010). In this latter case, Damijan, Kostevc, and Polanec (2010) found evidence of the learning-by-exporting hypothesis for medium and large Slovenian firms, i.e., the positive effect of exports on R&D, but failed to observe a positive impact of R&D on exports. It is apparent therefore that our results might be extrapolated for countries with similar characteristics to Portugal, that is, a small, peripheral and open country.

Our results have some important implications for firm management and for policy-makers. Managers should draw from our study that although both activities (exports and R&D) imply high costs and risks, being considered often as substitute activities, insofar as they compete for the companies’ finite resources (Roper and Love, 2002), they should not ignore the potential of carrying out the two activities simultaneously. Indeed, as we have shown, performing both activities simultaneously generates more benefits than adopting the two activities in isolation, suggesting that there is a positive interaction between them. However, as highlighted by Golovko and Valentini (2011), the fact that there is complementarity between the two activities is not to say that such complementarity exists for every firm, since it is assumed that this positive relationship depends on a large number of factors besides those included in the analyses.

The second main result from our study —carrying out the two activities (exports and R&D) generates synergies that positively affect sales growth— yields important policy implications. Specifically, innovation and export promotion policies should be articulated and carried out together, demanding the joint development of both activities rather than trying to implement separate policies for each activity, as is often the case given that such activities are usually designed by different and non-related government offices. For Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez (2013), these policies should be considered as part of a more comprehensive policy enhancing the firms’ market strength. This requires combining initiatives in order to reduce both sunk start-up costs in these activities and also enhance the firms’ absorptive technological capabilities in order to fully achieve the complementarities between exports and R&D. In peripheral countries such as Portugal, where firms do not have easy access to financing to support export and R&D activities, it is essential to devise proper policy measures that ensure that the given set of selected firms has access to funds so as to simultaneously develop these activities.

In addition to endogenous growth theory which is a strand of the literature stressing the importance of R&D for productivity growth (see, e.g., Romer, 1990), there are two more strands supporting a positive relationship between R&D and a firm's productivity growth (Mañez, Rochina-Barrachina, and Sanchis-Llopis, 2013). The first is based on the R&D capital stock model of Griliches (1979; 1980), and analyzes the relationship between R&D and productivity growth. The second is the active learning model (Ericson and Pakes, 1995), according to which investments in R&D contribute to improving the firms’ productivity over time.

Table 4 contains some descriptive statistics from the dataset in order to highlight the impact of the change of the accounting system that is used to report the information in the database.