This paper examines the factors determining the citation success of authors who have published via the Internet on the economic and business history of Spain. It departs from the dominant cross-sectional approach to the quantitative assessment of citation success by using a 15-year time series analysis of peer-reviewed Spanish and Latin American outlets. Moreover, it considers working papers published online, and assesses the role of Spanish as a medium to communicate with an international audience. Our results suggest a high concentration of publications and citations for a small number of authors (including non-residents) and the importance of local journals in citation success. Besides offering suggestions on how to improve scientific impact, our citation analysis also sheds light on the state of the field of economic and business history in Spanish economic circles and attests the role of Spain as an intermediate country in the production and diffusion of scientific knowledge.

Este trabajo examina cuáles son los factores determinantes del éxito en el número de citas obtenido por los autores que han publicado vía Internet sobre historia económica, historia de la empresa e historia de la contabilidad española. Nuestra evaluación se aleja del punto de vista dominante basado en análisis de corte transversal, introduciendo una base de datos temporal (15 años) que incluye publicaciones españolas y latinoamericanas sometidas a revisión por pares. Asimismo, se consideran los documentos de trabajo publicados online y se evalúa el papel del español como lengua de acceso a un público internacional. Nuestros resultados evidencian una alta concentración de publicaciones y citas en un reducido número de autores (incluidos los no residentes), así como la relativa importancia de las revistas locales para reforzar el número de citas. Este artículo ofrece indicios sobre cómo mejorar el impacto científico de las publicaciones del área y plantea nuevos puntos de vista sobre la situación de la historia económica y de la empresa en el entorno español, poniendo de manifiesto el papel de España como intermediario en la producción y difusión del conocimiento científico.

There has been a notable increase in the use of quantitative methods such as journal rankings and impact factors to ascertain the quality of academic publications, to the extent that in some circles quantitative measures to assess research quality now determine job promotion, university reputation, and even research project funding. As a result the number of citations of an author's work by other academic actors has been widely adopted as a measure of academic impact.

Although measuring citation success is relatively easy, its links with quality of research are doubtful as a higher success rate could be determined by factors other than its added value (Di Vaio et al., 2012). For instance, empirical studies tend to attract more citation than theoretical contributions (Johnston et al., 2012). Indeed, there is evidence to question the motivation of those making citations to the extent that, if true, ‘the phenomenon of citation would lose its role as a reliable measure of impact’ (Bornmann and Daniel, 2008) and could even be considered a futile exercise (Chang and McAlee, 2012; Crespo et al., 2011; Hoepner and Unerman, 2012; Hussain, 2012; Johnston et al., 2012; Lozano, 2012; Vanclay, 2012). Links between citation success and journal ranking have also been questioned on the grounds that increasing quantification can strangle specialists or emerging fields and inhibit innovation (Editorial, 2009; Wilson, 2012). This as high impact contributions are not the exclusive remit of high ranking, well established outlets.

Arguments about citation success can be particularly poignant to knowledge areas such as History where the diversity of topics and emphasises on documentary evidence (rather than agenda setting) result in most outlets having low citation impact scores and more so, for academic production outside of Anglo-Saxon countries. Yet some of these arguments are largely based on anecdotal evidence. Little is known of trends and directions of citations in the broad fields of economic and business history and, as noted by Baten and Muschalli (2012), about the scholars who are representing it. Moreover, to date there have been a handful of studies exploring the impact of the Internet on academic publishing (e.g. Boppart and Staub, 2012).

Glenn (1973) already noted the interest to map trends and directions in economic and business history as a single encompassing area of academic research. More recently, Baten and Muschalli (2012) claim that since the 1990s economic history has developed into a truly global discipline. However, only three economic history journals: Economic History Review, Explorations in Economic History and Journal of Economic History were included in the Journal Citation Reports (JCR) in 2007, thus ignoring the bulk of peer reviewed outlets that have economic history as their main field (Di Vaio and Weisdorf, 2010). Evidence documented in cross sectional studies by Di Vaio and Weisdorf (2010) and Di Vaio et al. (2012) tell that in spite of this rapid globalization, full professors, authors appointed at economics and history departments, and authors working in Anglo-Saxon and German countries were more likely to receive citations than other scholars. They also showed that length and co-authorships had a positive impact on citation success. As a novel feature, they demonstrate that the diffusion of research – publication of working papers, as well as conference and workshop presentations – has a first-order positive impact on the citation rate. Evidence documented in Eloranta et al. (2010) and Valtonen et al. (2011) comment on developments in business history, where apparently citation success was ‘higher for scholars coming from ‘outside’ the fluid disciplinary core of the field’.

Alongside international studies, there has been an interest in bibliometric research exploring Spanish scientific production since at least 1992.1 These studies include the pioneering contribution by Lafuente Félez and Oro (1992), which was quickly followed by others such as those by Oriol Amat (Amat et al., 1998, 2001; Amat and Oliveras Sobrevias, 1999, 2001), FUNCAS (1999), Boyns and Carmona (2002), Tedde de Lorca (2004), Tirado Fabregat and Pons Novella (2006), and more recently Buela-Casal et al. (2011); and Crespo et al. (2011); Gutierrez-Hidalgo and Baños-Sánchez Matamoros (2010). In this body of work there is a clear interest in economic, business and accounting research but seldom has any attention been given to business history while accounting and economic history are dealt in isolation and appear as distinct subject areas.

While there has been no comprehensive study of the broad but related areas of accounting, business and economic history of Spain, there has been a significant increase in the number of working papers, pre-publication and actual publication items that appear online. Anderson et al. (2001) already compared the performance of printed and online articles from the early days of the Internet (i.e. 1997–1999). Presumably citation and impact factor patterns have changed since then. Evans (2008) argues that as more journal articles were digitalised and became available online, references tended to be more recent, and more of those citations were made to fewer journals and articles. However, evidence in Lozano (2012) claims that the best (i.e. most cited) work now comes from increasingly diverse sources, irrespective of the journals’ impact factor. Hence there is room to further explore not only trends and directions of the business and economic history of Spain but also the role of online publications in citation patterns.

What follows sheds a first light regarding the importance of citation success in Spanish business and economic history circles and whether there is enough evidence to suggest that online publication results in higher citation success. The remainder of the article maps as follows: Section 2 describes the dataset and selection criteria. Here it is noted that the unit of analysis is Spain rather than the production by Spanish scholars. This undervalues the productivity of individual authors (who might be contributing to different fields) as well as outlets without an Internet presence. The next two sections offer and comment on descriptive statistics: first regarding authorship (Section 3) and second, on outlets (Section 4). Section 5 reconsiders trends in descriptive statistics through an econometric analysis. Section 6 concludes.

2DatasetAn initial hurdle to explore whether research published online had an impact on citation success was establishing the boundaries of contributions to the economic, business and accounting history of Spain. All potential objective measures (such as JEL codes) suffered from shortcomings as they were asked to combine overlapping knowledge areas with a specific geography. Instead the research adopted an inductive approach to data collection. It started by identifying working papers published online within a digital library called Research Papers in Economics (RePEc, http://repec.org) (see further Bátiz-Lazo and Krichel, 2012).

RePEc is a decentralised database that links to a single location more than 1.2 million research outputs online.2 It offered the possibility to systematically identify working papers from other research outputs by searching the archives of a weekly report that was launched in May 1997 entitled New Economic Papers in Business, Economic and Financial History (nep-his, http://nep.repec.org).3 This weekly report had the advantage of having being edited by the same person throughout the analysis period.

Data collection started in October 2011. A search of Spain or Spanish4 in the title, abstract or keyword was the main criteria to determine the boundaries of online working papers on the accounting, business and economic history of Spain. The selection criteria also considered studies dealing with events prior to the 1700s and formation of Spain as a nation state as well as working papers dealing with the colonial period. To be included as part of the sample the latter were required to have a clear reference to the study of some form of interaction between the colonies and activities within the metropolis.

A shortcoming during data collection was the potential failure to identify relevant research outputs (hence forth “items”) that did not include Spain or Spanish in their title, abstract or keyword (for instance, research into the Kingdom of Aragon). Another shortcoming was that the search criteria would underestimate the productivity of authors who contribute to related topics (such as Latin America) rather than focusing into researching the history of Spain. To assess the strength of the criteria to identify online working papers within RePEc, the same criteria in searching the title, abstract or keywords were applied to identify online working papers in a second digital library, namely the Social Science Research Network (SSRN.com), which stored 500,000 items online.5 On balance, it was deemed that the selection criteria were robust (but subject to the afore mentioned limitations).

The search for online research outputs was extended to identify relevant items within peer-reviewed journals. This set built upon the 14 outlets on economic history used by Di Vaio et al. (2012),6 of which nine were found to carry items that met our selection criteria. The list of 14 outlets was used as prompt in a survey of chief editors of accounting and business history journals. They identified 38 potential outlets of which 27 carried items that met our selection criteria. In tandem and with the aim of eliciting suggestions of other potential relevant outlets, the list of 14 outlets was posted to the main mailing lists of economic and business history in Spain7 and Latin America8 as well as personal communications (email) to relevant learned societies, namely Latin America economic history associations (specifically Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and Uruguay) and the US-based Academy of Accounting Historians. These mailings resulted in seven innovations, which included two other digital libraries9 and from which 17 peer-reviewed journals with Internet presence were identified. These then took to 53 the total number of outlets found to have published a total of 864 items that met our criteria.10

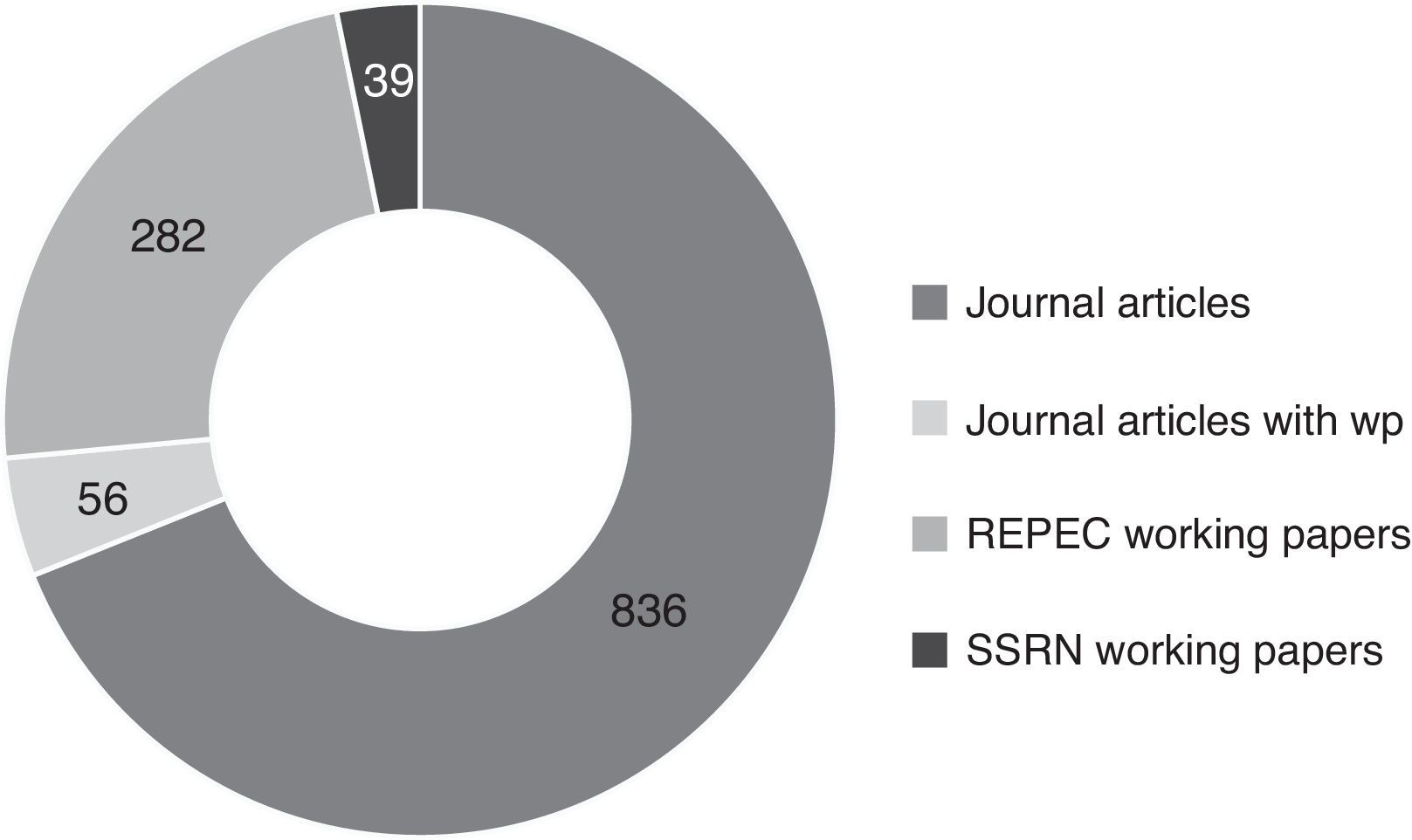

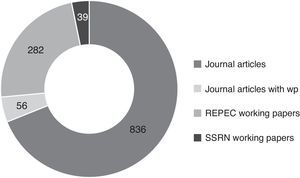

Fig. 1 summarises the total dataset, which encompassed 1109 items. There were 56 journal papers (5% of total items) with a matching online working paper (49 of them in RePEc and eight in SSRN) and 808 (73%) had no matching working paper. There were an additional 301 online working papers without journal article of which RePEc linked to 215 (19%) and SSRN stored 30 (3%).

The dataset compares handsomely with other systematic studies of citation success. For instance, the study of economic history by Di Vaio et al. (2012) encompassed 657 citations from 217 research articles published in 2007 within 14 international peer-reviewed outlets with general-interest in economic history. They collected information for 450 authors and sourced their citation data from the survey of major economics journals by Kalaitzidakis et al. (2010).

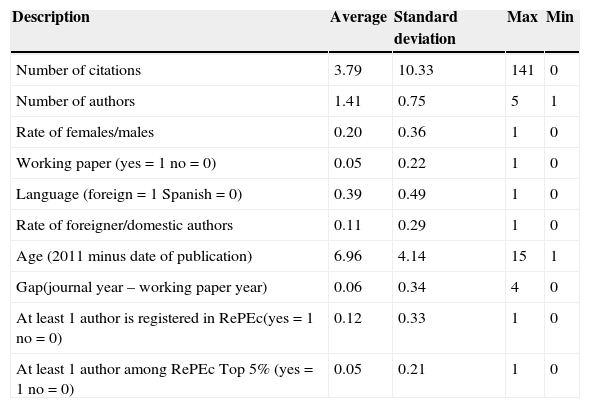

As summarised in Table 1, data were extracted for each item to ascertain the characteristics of the sample. This characterisation included the number of citations as measured by Harzing's ‘Publish or Perish’ software (Harzing, 2010), number of authors, percentage of female authors, language, percentage of non-resident authors, age of the publication, the time gap between the posting of the online working paper and publication date of the refereed paper, a ranking of the outlet, and whether at least one of the authors was registered in the RePEc digital library. Values in Table 1 tell that the average item was 7 years old (st. dev. of 4.1, mode and median equal to 1). The average item was written mainly by one author, and one out of five was a female, while there was only a 5% chance to find an online working paper for the item and only 11% of authors were non-residents. Of the 1109 items, 667 items (60%) were written in Spanish and 442 (40%) were written in other medium (mainly English).

Selection of average values per item.

| Description | Average | Standard deviation | Max | Min |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of citations | 3.79 | 10.33 | 141 | 0 |

| Number of authors | 1.41 | 0.75 | 5 | 1 |

| Rate of females/males | 0.20 | 0.36 | 1 | 0 |

| Working paper (yes=1 no=0) | 0.05 | 0.22 | 1 | 0 |

| Language (foreign=1 Spanish=0) | 0.39 | 0.49 | 1 | 0 |

| Rate of foreigner/domestic authors | 0.11 | 0.29 | 1 | 0 |

| Age (2011 minus date of publication) | 6.96 | 4.14 | 15 | 1 |

| Gap(journal year – working paper year) | 0.06 | 0.34 | 4 | 0 |

| At least 1 author is registered in RePEc(yes=1 no=0) | 0.12 | 0.33 | 1 | 0 |

| At least 1 author among RePEc Top 5% (yes=1 no=0) | 0.05 | 0.21 | 1 | 0 |

Only 137 items (12% of the total) had contributors who were amongst the 33,892 persons registered in RePEc. But consistently with the rankings of the latter, 52 items (5%) resulted from contributions by at least one author having been ranked by RePEc as one of its Top 5% most cited authors.11

Given the size of the sample it was not cost effective at this stage to distinguish between field area (accounting, business or economics), time period studied by the item, author's employer, whether any of the authors was an editor or member of the editorial board of the outlet and other interesting characteristics that would help ascertaining the state of the art in the field. The remainder of this paper comments on the values that were extracted.

3Trends in the history of Spain: the authorsAs noted above, the sample potentially underestimates the productivity of authors as it would be expected that only a handful would focus their production within the strict limits of our criteria. Nevertheless it was deemed important to explore authors’ characteristics and citation success within the database as an approximation to the potential behaviour of the whole field.

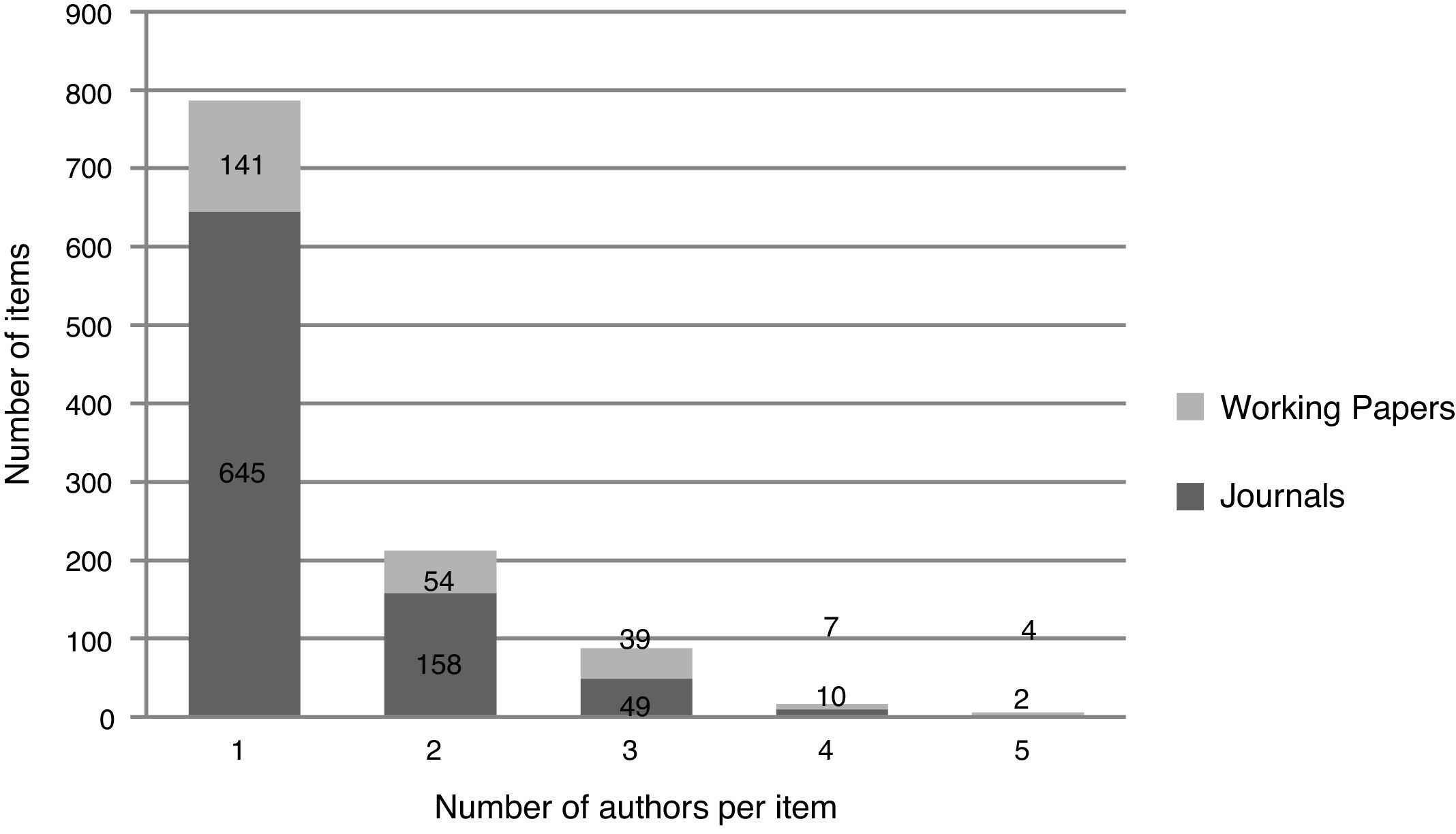

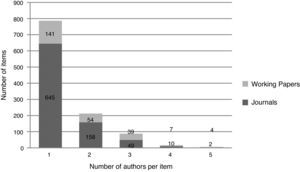

The search identified 870 individual authors of which 193 were females (22% of all authors) and 128 were non-residents (15%). Non-residents were mainly based in the USA (30 authors or 23% of non-residents) and the United Kingdom (30 authors or 23% of non-residents). But as a geographical block, the European Union housed 77 non-resident authors (60% of non-residents) whereas the Americas housed 48 (38%) and other locations 3 (2%). On average an individual contributed to 1.73 items.12Fig. 2 shows that there were 786 items written by a single author and these represented 70% of the sample, while 323 items were authored by two or more persons and represented only 30% of the sample.

An average contribution of two papers per author in the 15 years between 1997 and 2011 is only partially explained by the production of single author monographs and edited books, which together encompass an important part of knowledge creation within the broad areas of business and economic history. Single author monographs usually require more time and effort to produce and have a longer ‘shelf life’ than journal articles, but since they were excluded from our sample it is left to future research to ascertain their relative importance. Individual productivity would probably increase if the search criteria started from author's own curricula, that is, encompassing all related fields in which resident authors have contributed since 1997, rather than extracting names from research outputs as in our selection criteria.

A total of 872 author names were identified in the sample, which generated 1570 contributions (regardless of whether these were single or multiple authored items). A total of 41 authors (5% of all authors) generated 342 contributions (22% of all contributions in the sample). There were 267 names (31%) which appeared in two or more contributions. These 267 names accrued 955 contributions (61%) while 615 names (71%) generated 615 contributions (39%). This suggested that, in spite of a large number of contributors, citation success concentrated around a small number of individuals within the sample. This conclusion should be taken with care as it would only be valid should individual productivity was well within the limits of the selection criteria.

Male authors dominated the production of research outputs within the sample. Males were responsible for 824 items (74% of all items in the sample). One female author appeared in 244 items (24%), two females in 38 items (3%) and only 3 items (0.5%) had three female authors. In most cases females were the sole author of the item (170 items or 15%). They were joint authors in a 2-author paper in 61 items (6%) and 27 items (2%) resulted from three female authors.

There were 951 items authored solely by residents (86% of total items). There were 142 items (12%) with contributions by a single non-resident, two non-residents appeared in 11 items (1%) and only five items (0.5%) had 3 non-resident authors. In most cases non-residents were the sole author of the item (98 items or 9%), 35 items (3%) resulted from a two-author paper (where at least one of the authors was non-resident) and 14 items (1%) by three authors (where at least one of the authors was non-resident).

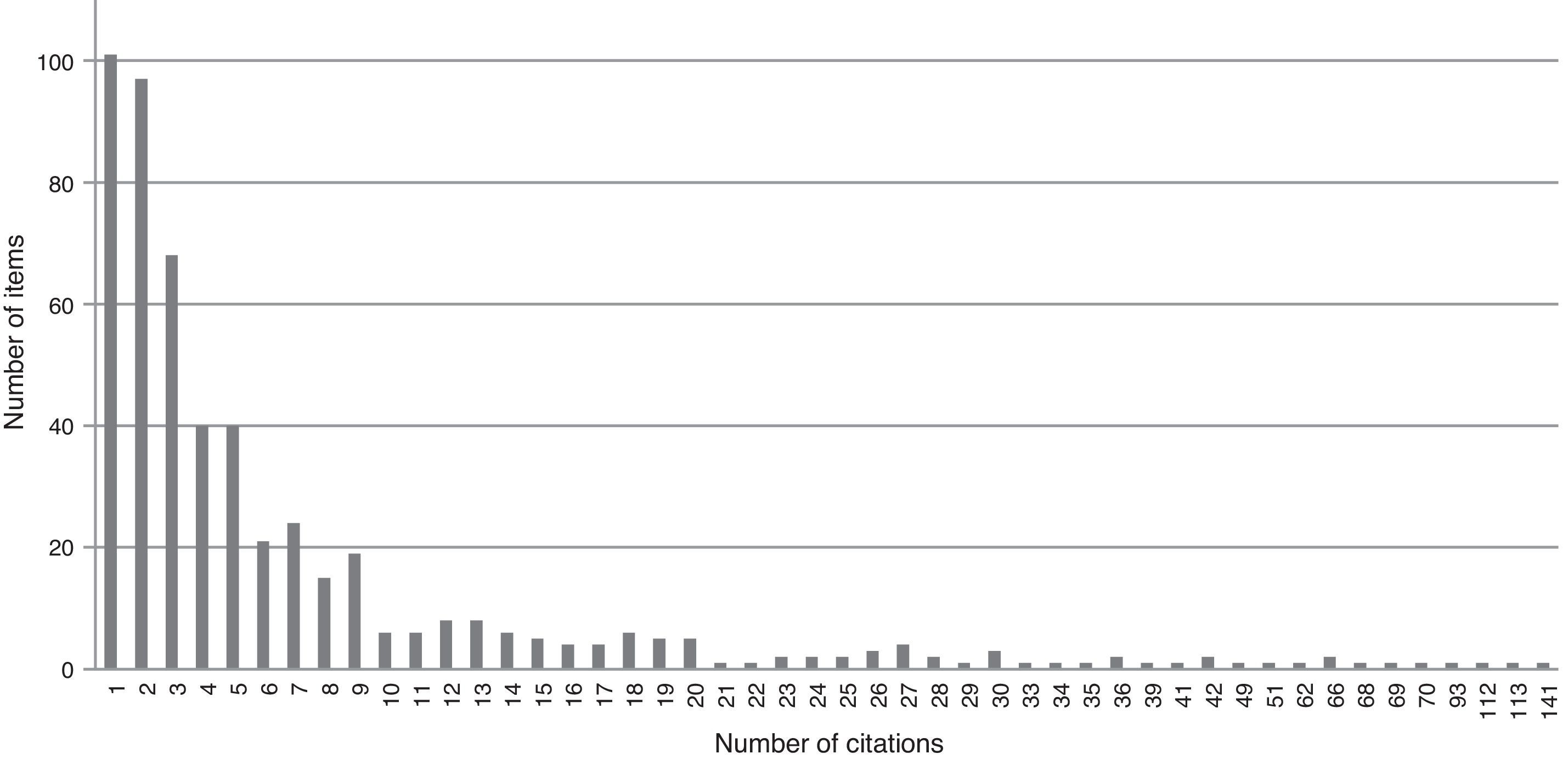

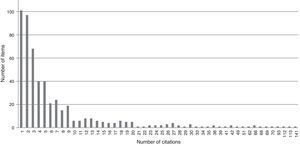

Germaine to this article is the number of citations. Fig. 3 illustrates the frequency distribution of the number of citations per individual item. This distribution excludes the highest observation, namely that zero citations were recorded for 579 items (52% of all items in the sample). The cumulative frequency for 9 or less items was 91% of all items in the sample. This quantifies the expectation that the emphasis on documentary evidence and single author monographs would result in low citation values. However, Fig. 3 shows that less than 10% of the items in the sample accrued 10 or more citations, again suggesting a high concentration of citation success within the sample.

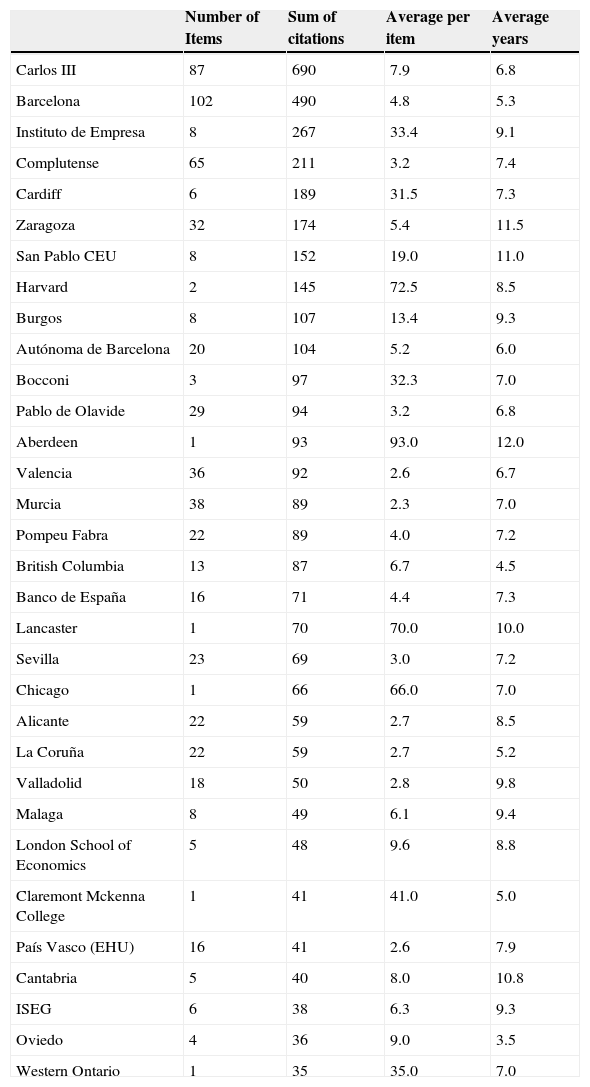

Table 2 illustrates the top contributors in the sample in terms of citation success. This exhibit built on a subset of 464 of the 871 authors, which included all authors with two or more items and a random selection of authors with only one item. The current employer of each author was identified. Estimates for the home institution were then aggregated for the number of citations regardless of whether there was a single or there were multiple authors. The estimates in Table 2 are thus somewhat incomplete and overstate citation success. But it is the trends rather than exact measures, which are of relevance. For instance, the London School of Economics and Political Science is the only London-based institution named in Table 2 (while Oxford and Cambridge colleges are poignantly absent). At the top of Table 2 there are four domestic institutions, which house a large group of researchers in business and economic history. In contrast, researchers based in foreign institutions seem more adept at citation success by consistently generating a higher average value of citation per item than domestic institution. This last trend is further explored in Table 3.

Most cited items by home institution, 1997–2011 (citation estimates using Harzing's Publish or Perish, as of October 2011; single and multiple author contributions have the same weight).

| Number of Items | Sum of citations | Average per item | Average years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carlos III | 87 | 690 | 7.9 | 6.8 |

| Barcelona | 102 | 490 | 4.8 | 5.3 |

| Instituto de Empresa | 8 | 267 | 33.4 | 9.1 |

| Complutense | 65 | 211 | 3.2 | 7.4 |

| Cardiff | 6 | 189 | 31.5 | 7.3 |

| Zaragoza | 32 | 174 | 5.4 | 11.5 |

| San Pablo CEU | 8 | 152 | 19.0 | 11.0 |

| Harvard | 2 | 145 | 72.5 | 8.5 |

| Burgos | 8 | 107 | 13.4 | 9.3 |

| Autónoma de Barcelona | 20 | 104 | 5.2 | 6.0 |

| Bocconi | 3 | 97 | 32.3 | 7.0 |

| Pablo de Olavide | 29 | 94 | 3.2 | 6.8 |

| Aberdeen | 1 | 93 | 93.0 | 12.0 |

| Valencia | 36 | 92 | 2.6 | 6.7 |

| Murcia | 38 | 89 | 2.3 | 7.0 |

| Pompeu Fabra | 22 | 89 | 4.0 | 7.2 |

| British Columbia | 13 | 87 | 6.7 | 4.5 |

| Banco de España | 16 | 71 | 4.4 | 7.3 |

| Lancaster | 1 | 70 | 70.0 | 10.0 |

| Sevilla | 23 | 69 | 3.0 | 7.2 |

| Chicago | 1 | 66 | 66.0 | 7.0 |

| Alicante | 22 | 59 | 2.7 | 8.5 |

| La Coruña | 22 | 59 | 2.7 | 5.2 |

| Valladolid | 18 | 50 | 2.8 | 9.8 |

| Malaga | 8 | 49 | 6.1 | 9.4 |

| London School of Economics | 5 | 48 | 9.6 | 8.8 |

| Claremont Mckenna College | 1 | 41 | 41.0 | 5.0 |

| País Vasco (EHU) | 16 | 41 | 2.6 | 7.9 |

| Cantabria | 5 | 40 | 8.0 | 10.8 |

| ISEG | 6 | 38 | 6.3 | 9.3 |

| Oviedo | 4 | 36 | 9.0 | 3.5 |

| Western Ontario | 1 | 35 | 35.0 | 7.0 |

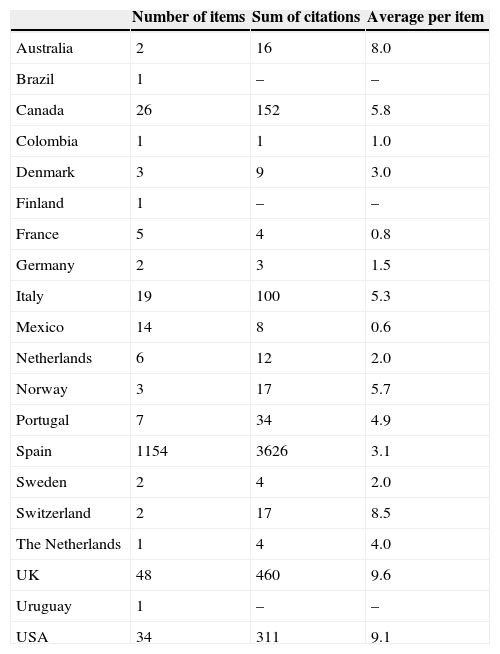

Most cited items by home country, 1997–2011 (citation estimates using Harzing's Publish or Perish, as of October 2011; single and multiple author contributions have the same weight).

| Number of items | Sum of citations | Average per item | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 2 | 16 | 8.0 |

| Brazil | 1 | – | – |

| Canada | 26 | 152 | 5.8 |

| Colombia | 1 | 1 | 1.0 |

| Denmark | 3 | 9 | 3.0 |

| Finland | 1 | – | – |

| France | 5 | 4 | 0.8 |

| Germany | 2 | 3 | 1.5 |

| Italy | 19 | 100 | 5.3 |

| Mexico | 14 | 8 | 0.6 |

| Netherlands | 6 | 12 | 2.0 |

| Norway | 3 | 17 | 5.7 |

| Portugal | 7 | 34 | 4.9 |

| Spain | 1154 | 3626 | 3.1 |

| Sweden | 2 | 4 | 2.0 |

| Switzerland | 2 | 17 | 8.5 |

| The Netherlands | 1 | 4 | 4.0 |

| UK | 48 | 460 | 9.6 |

| Uruguay | 1 | – | – |

| USA | 34 | 311 | 9.1 |

Table 3 suggests the pre-eminence of researchers based in the European Union as contributors to the economic and business history of Spain. Again, foreign researchers and specifically those based in British universities seem particularly effective at citation success. Moreover, an average value of 3.1 citations per item for researchers at Spanish institutions is below the average of 3.6 citations per item for Table 3 However, the picture coming out of Tables 2 and 3 is not all together clear as the average number of years since publication (shown in the last column to the right of Table 2) seems to have a positive influence in citation success (more below).

Individual inspection of the top 25 items as measured by citation success, suggested that most of these had been published in international, peer-reviewed outlets, but the importance of local publications could not be underestimated (as is the case of Papeles de Economía Española – see Table 3). The production of single authored items within the top 25 items as measured by citation success, was less acute than otherwise suggested by the frequency distribution in Fig. 2. There were more joint publications than expected and many of these in collaboration with non-residents than suggested by average values. It is also worth noting the importance of publications in accounting history as many of these were placed at the top of the citation success ranking. This suggests there are opportunities and indeed, significant rewards for historical studies to collaborate with colleagues in business schools in order to inform broader areas of knowledge (and in particular those within business/management and economics).

The list of top 25 cited items also suggested many of the top items published an online working paper, thus creating opportunities for higher citation success. Indeed, the 56 items with an online working paper (5% of the total number of items) accrued 526 citations (12% of the total number of citations). Most of the online versions were published the year before the journal article (24 items or 43%) or the same year as the journal article (15 items or 27%). Another group of online versions were made available two years (12 or 21%), three years (3 or 5%) and even four years (2 or 4%) before the journal article appeared.

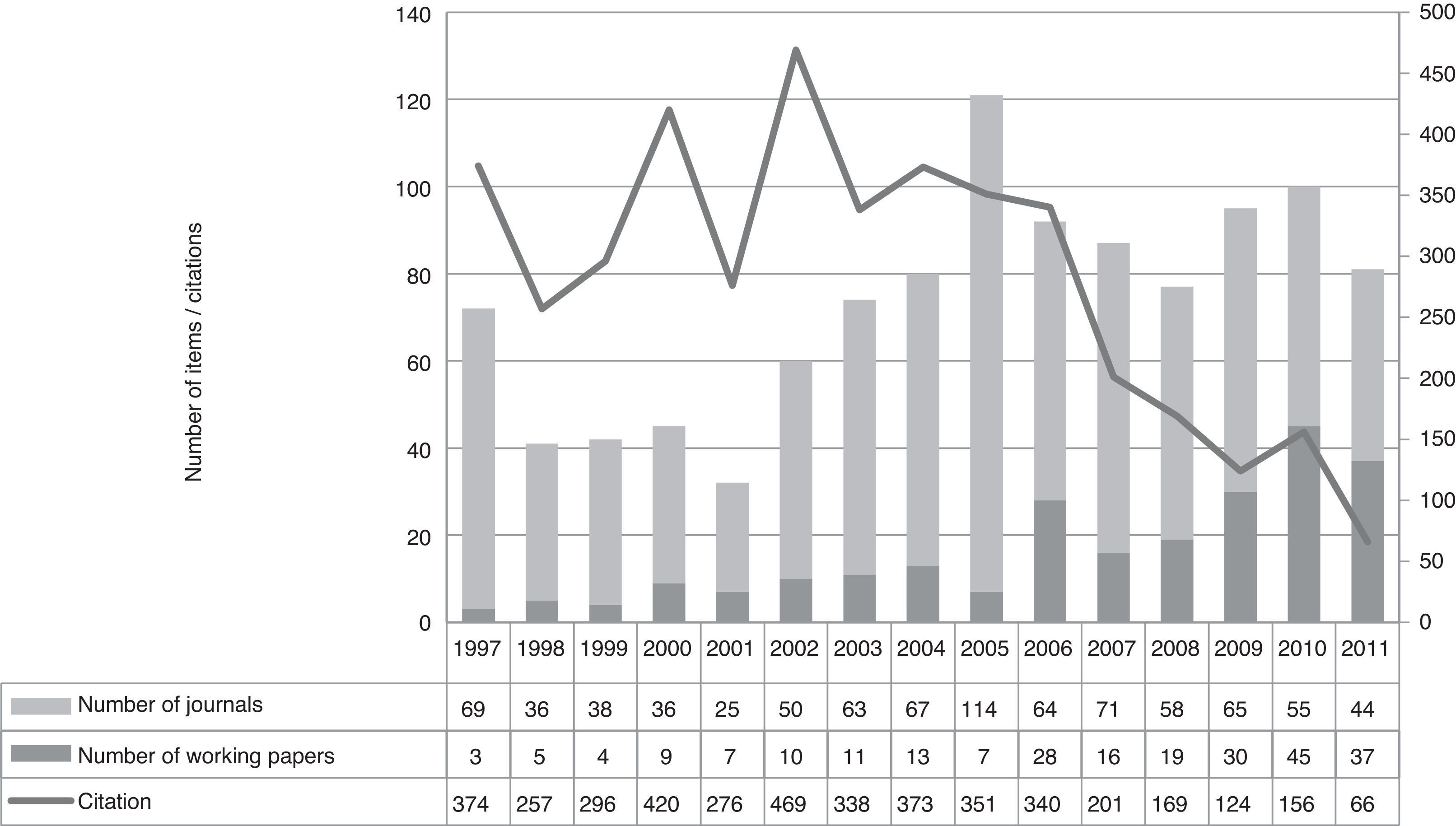

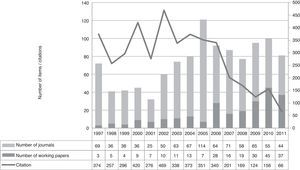

Fig. 4 maps the long-term behaviour for aggregate citation success, peer-reviewed, and online items. It suggests that citation success reaches its highest point seven years after publication. Indeed, 19 top 25 cited items were published before 2005, and only 6 out of the 25 top cited items were published after 2005. Fig. 4 also tells that there has been an increase in the number of online working papers since 2006. The recent rise in online items could explain the small overlap between online working papers and peer-reviewed articles across the 1997–2011 period observed before (i.e. 56 out of the 1109 items).

There is no evident reason to explain the rise to 121 total items in 2005. Nor could we explain the drop to 32 items in 2001 depicted in Fig. 4. But it is clear that the production of both peer-reviewed and online research outputs has increased since 2006.

4Trends in the history of Spain: the outletsOf the 53 outlets, 12 (21%) were open source while the rest published behind a fee-paying platform (41 outlets or 79%).13 The fee-paying outlets housed 533 items (48%), the 12 open source outlets held 331 items (30%) and there were 245 online working papers (22%) freely available through open digital libraries. Open source items accrued 787 citations (19% of total citations in the sample) and online working papers had 777 citations (18%). Items published in fee-paying outlets amassed 2646 citations (63%), pointing to the importance of certain outlets for citation success. Meanwhile, the 56 items (5%) that had both a peer-reviewed publication and an online working paper accrued 529 citations (13%), suggesting a positive and complementary effect of online publication but too recent to have had a significant effect on overall citation success.

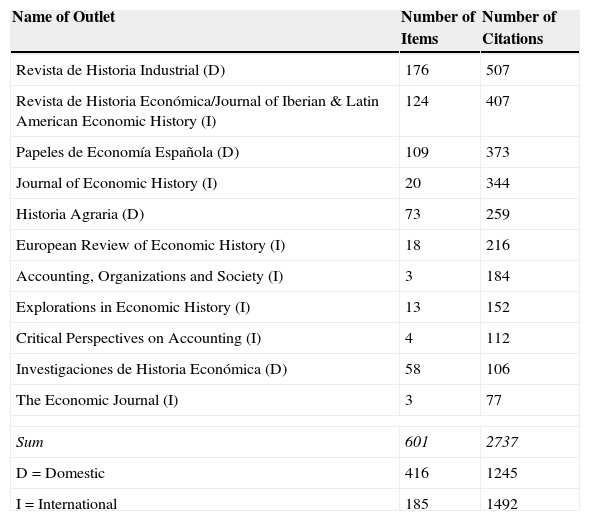

Table 4 shows 11 outlets (21% of the 53 peer-reviewed outlets) housed 601 items (54% of the 1109 total items) which accrued 2737 citations (65% of the 4210 total citations).14Table 4 also identifies a number of domestic and international outlets. Seven international outlets (13% of peer-reviewed outlets) dominate the list in Table 4 in terms of impact as they housed 185 items (17% of total items) but amassed 1492 citations (35% of total and 55% of those in Table 4). Four domestic outlets (7% of peer-reviewed outlets) housed 416 items (38% of total items) but accrued 1245 citations (30% of total citations and 45% of those in Table 4). In other words, a publication in a top international outlet accrued 8 citations on average while a domestic outlet only accrued 3 citations on average. It is interesting to note that both accounting and economic history journals have a very important presence in Table 4 where there is not one of the business history outlets with international repute.

Outlets with the largest number of citations and items, 1997–2011.

| Name of Outlet | Number of Items | Number of Citations |

|---|---|---|

| Revista de Historia Industrial (D) | 176 | 507 |

| Revista de Historia Económica/Journal of Iberian & Latin American Economic History (I) | 124 | 407 |

| Papeles de Economía Española (D) | 109 | 373 |

| Journal of Economic History (I) | 20 | 344 |

| Historia Agraria (D) | 73 | 259 |

| European Review of Economic History (I) | 18 | 216 |

| Accounting, Organizations and Society (I) | 3 | 184 |

| Explorations in Economic History (I) | 13 | 152 |

| Critical Perspectives on Accounting (I) | 4 | 112 |

| Investigaciones de Historia Económica (D) | 58 | 106 |

| The Economic Journal (I) | 3 | 77 |

| Sum | 601 | 2737 |

| D=Domestic | 416 | 1245 |

| I=International | 185 | 1492 |

The apparent distribution of citations and outlets led to consider quantitative impact factors. Only 19 of the 53 outlets were indexed by the Social Science Citation Index (averaging 1.02 impact factor) and 20 outlets were found in Scopus (averaging 0.22). The highest ranked outlet Social Science Citation Index in the sample was Economics & Human Biology (2.43) followed by Explorations in Economic History (1.22). Meanwhile in Scopus the highest ranked outlet was the Journal of Latin American Studies (0.49), followed by the Economic History Review (0.43). These rankings suggested apparent greater success in citations by publishing in multidisciplinary journals rather than specialist outlets.

However, both Scopus and the Social Science Citation Index exclude outlets we have described as ‘domestic’ in Table 4. The same table shows they play an important part in disseminating the economic, business and accounting history of Spain. Hence, two alternative and ‘ad hoc’ measures of output quality were manufactured. One labelled ‘Anglo Saxon’ averaged the ranking for each of the 53 outlets given by the journal ranking of the Association of Business Schools in the UK15 together with the ranking of the Australian Research Council.16 The second construct was labelled ‘Spanish’ and it resulted from averaging the rankings by IN-RECS at Granada University17 and Carhus Plus by the Generalitat de Catalunya.18 Admittedly, the assessment of quality is a categorical variable and performing an arithmetic operation is not defined. However, it was interesting to note how individual outlets changed, as there was little agreement between the four sources described above but some harmony when grouped as suggested in Table 5.

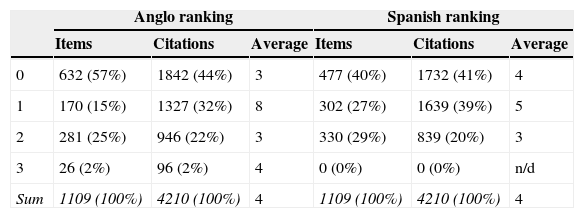

Frequency of items and citations by impact factor, 1997–2011.

| Anglo ranking | Spanish ranking | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | Citations | Average | Items | Citations | Average | |

| 0 | 632 (57%) | 1842 (44%) | 3 | 477 (40%) | 1732 (41%) | 4 |

| 1 | 170 (15%) | 1327 (32%) | 8 | 302 (27%) | 1639 (39%) | 5 |

| 2 | 281 (25%) | 946 (22%) | 3 | 330 (29%) | 839 (20%) | 3 |

| 3 | 26 (2%) | 96 (2%) | 4 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | n/d |

| Sum | 1109 (100%) | 4210 (100%) | 4 | 1109 (100%) | 4210 (100%) | 4 |

Note: 3 is taken to be ‘world elite’; 2 original and well executed research (mainly domestic with some international reputation); 1 is purely domestic (research of acceptable standard); and 0 modest standard journals or not found in ranking.

Results in Table 5 suggest most papers would be ranked at the lowest quality outlet. Indeed and even though most online working papers series have some form of editorial control or peer review, they are not part of any ranking and therefore were awarded a zero for purposes of classification in Table 5. However, given the domestic nature of the sample (i.e. large number of items in Spanish) it is not surprising that the ‘Anglo’ ranking has a much higher proportion of items in this category namely 632 items (57%) versus 447 (40%) for the Spanish ranking.

There was no agreement in the top quality bracket. The ‘Anglo’ ranking identified at least 26 items (2%) within ‘world elite’ outlets, while there were none in this category for the ‘Spanish’ ranking. The reason for this had to do more with disagreement between the scales used within the ‘Spanish’ ranking. In other words, the scales with the ‘Anglo’ ranking were more likely to be in agreement towards the ranking of an outlet than the ‘Spanish’ scales.

Surprisingly it was the tier 1 classification which resulted in greater citation success. Both ‘Anglo’ and ‘Spanish’ observed 8 and 5 items on average respectively, which was higher than average 4 citations per item. This result points to the importance of a publication strategy that includes ‘domestic’ journals. They might not be characterised by publishing leading, original research but they certainly have an audience. Moreover, in the case of the business and economic history of Spain, this audience spreads out through Latin America. In other words, for this area of knowledge, communication of research results in a medium other than English seems important for citation success and hints to the role of Spanish academic circles as intermediaries between Anglo-Saxon and Latin American research agendas.

5Econometric estimateAn ‘ad hoc’ model of citation success was built while assuming that citation success would be a function of three elements, namely author characteristics, outlet characteristics and time lag or the number of years between publication and data collection.

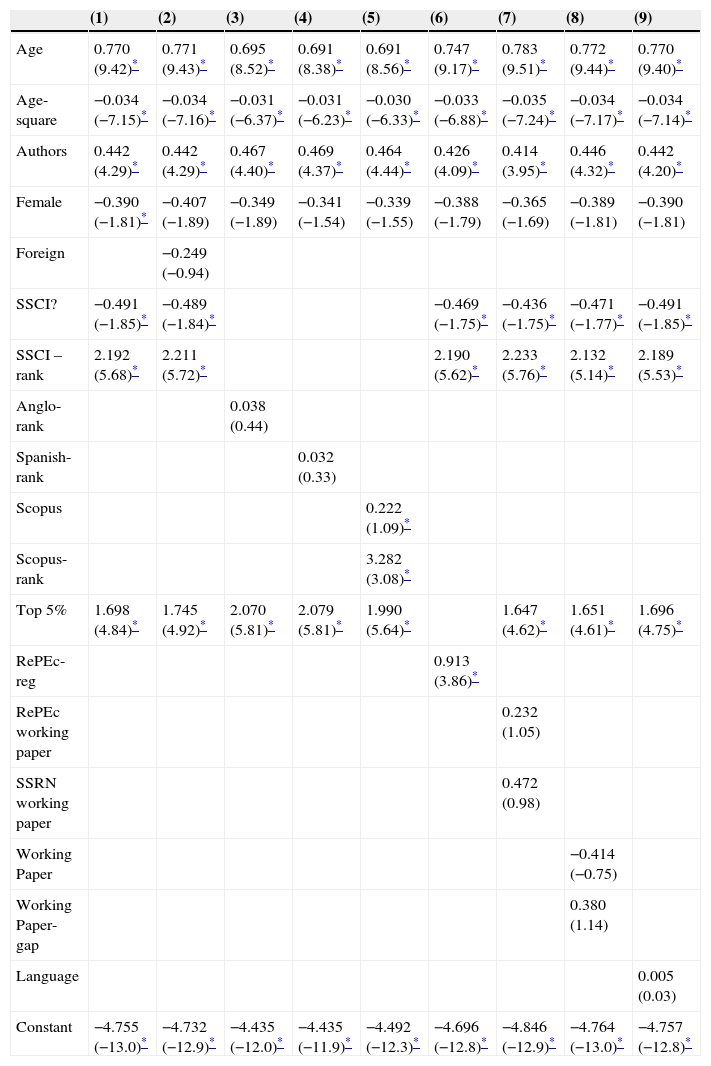

Table 6 summarises results of the econometric analysis. The dependent variable in all estimations of a tobit regression was the natural logarithm of the number of citations, where observations with zero citations were treated as left-censored. In Table 6, t-statistics are reported in parentheses and numbers 1–9 denote alternative estimates of the model.

Tobit estimates of citation success, 1997–2011.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.770 (9.42)* | 0.771 (9.43)* | 0.695 (8.52)* | 0.691 (8.38)* | 0.691 (8.56)* | 0.747 (9.17)* | 0.783 (9.51)* | 0.772 (9.44)* | 0.770 (9.40)* |

| Age-square | −0.034 (−7.15)* | −0.034 (−7.16)* | −0.031 (−6.37)* | −0.031 (−6.23)* | −0.030 (−6.33)* | −0.033 (−6.88)* | −0.035 (−7.24)* | −0.034 (−7.17)* | −0.034 (−7.14)* |

| Authors | 0.442 (4.29)* | 0.442 (4.29)* | 0.467 (4.40)* | 0.469 (4.37)* | 0.464 (4.44)* | 0.426 (4.09)* | 0.414 (3.95)* | 0.446 (4.32)* | 0.442 (4.20)* |

| Female | −0.390 (−1.81)* | −0.407 (−1.89) | −0.349 (−1.89) | −0.341 (−1.54) | −0.339 (−1.55) | −0.388 (−1.79) | −0.365 (−1.69) | −0.389 (−1.81) | −0.390 (−1.81) |

| Foreign | −0.249 (−0.94) | ||||||||

| SSCI? | −0.491 (−1.85)* | −0.489 (−1.84)* | −0.469 (−1.75)* | −0.436 (−1.75)* | −0.471 (−1.77)* | −0.491 (−1.85)* | |||

| SSCI –rank | 2.192 (5.68)* | 2.211 (5.72)* | 2.190 (5.62)* | 2.233 (5.76)* | 2.132 (5.14)* | 2.189 (5.53)* | |||

| Anglo-rank | 0.038 (0.44) | ||||||||

| Spanish-rank | 0.032 (0.33) | ||||||||

| Scopus | 0.222 (1.09)* | ||||||||

| Scopus-rank | 3.282 (3.08)* | ||||||||

| Top 5% | 1.698 (4.84)* | 1.745 (4.92)* | 2.070 (5.81)* | 2.079 (5.81)* | 1.990 (5.64)* | 1.647 (4.62)* | 1.651 (4.61)* | 1.696 (4.75)* | |

| RePEc-reg | 0.913 (3.86)* | ||||||||

| RePEc working paper | 0.232 (1.05) | ||||||||

| SSRN working paper | 0.472 (0.98) | ||||||||

| Working Paper | −0.414 (−0.75) | ||||||||

| Working Paper-gap | 0.380 (1.14) | ||||||||

| Language | 0.005 (0.03) | ||||||||

| Constant | −4.755 (−13.0)* | −4.732 (−12.9)* | −4.435 (−12.0)* | −4.435 (−11.9)* | −4.492 (−12.3)* | −4.696 (−12.8)* | −4.846 (−12.9)* | −4.764 (−13.0)* | −4.757 (−12.8)* |

In ascertaining the values in Table 6, Harzing's ‘Publish or Perish’ software provided a measure for the number of citations (Harzing, 2010). Independent variables were extracted from individual records and included the number of years since initial publication (age), the number of authors (authors), percentage of female authors (female), percentage of authors resident outside of Spain (foreign).

These were followed by six measures of academic impact, namely a dichotomous variable identified whether the item was published in an outlet considered by Thomson's Social Science Citation Index (SSCI) and if so, the index's value (SSCI-rank). A dichotomous variable identified whether the item was published in an outlet considered by Elsevier's Scopus database (Scopus) and if so, the index's value (Scopus-rank).

Two alternative and ‘ad hoc’ measures of output quality were manufactured as above mentioned (one labelled ‘Anglo Saxon’ and the second construct was labelled ‘Spanish’). As mentioned, the chief reason to combine these indexes was that both Scopus and the Social Science Citation Index exclude outlets that have described as ‘domestic’ (where manual inspection suggested a large number of items had been published). ‘Domestic’ outlets mostly published in Spanish and out ‘ad hoc’ measures thus enabled an opportunity to systematically assess the potential of impact of non-English communications in citation success within the sample. Admittedly, creating ‘ad hoc’ categorical variables reduced degrees of freedom of inferential statistics. But as noted, manual inspection suggested there was little agreement between the four public rankings, thus potentially increasing variance, while, at the same time, there was a degree of harmony in the ranking of outlets when grouped through our innovations.

Independent variables also identified whether at least one of the authors was registered in RePEc digital library (RePEc-reg) and also whether it was within the top five per cent of citations in that database (top 5%). Dichotomous variables identified whether there was an online working paper in RePEc (RePEc working paper), SSRN (SSRN working paper) or both (working paper) as well as whether the paper was written in Spanish (language). Estimates also included the difference in years between publication in a peer reviewed outlet and the online working paper (working paper-gap).

In Table 6 equation (1) is the preferred model, with all coefficients significant at the 0.1 level or lower. Equation (2) added the proportion on foreign authors (insignificant). Equations (3) and (4) substituted ‘Anglo ranking’ and ‘Spanish ranking’ respectively for the Thomson's SSCI ranking (both were not significant). Equation (5) substituted the Scopus ranking for the Thomson's SSCI ranking, both were significant, but Thomson's SSCI ranking was more significant. Equation (6) substituted the RePEc-registered dichotomous variable for the top 5% dummy, both of which were significant but the ‘top 5%’ was more significant. Equation (7) includes the dichotomous variables for RePEc and SSRN working papers, both were not significant. Equation (8) included the dichotomous variable for previous publication as a working paper, and the gap between working paper and article publication but neither was significant. Equation (9) included the language dummy, which was also not significant.

6Discussion and conclusionsAs noted from the start, design of the selection criteria involved some compromises in terms of limiting the subject area and generalising results around authors. There were other likely sources of bias, which were particularly important when interpreting regression results, namely self-citation and the age of the paper. With regard to the first, Harzing's ‘Publish or Perish’ only offers a raw estimate of citations because she considers that excluding them is ‘normally not worthwhile’ (Harzing, 2010). Estimates by Aksnes (2006) suggest a strong positive correlation between the number of authors and self-citations but that the percentage of self-citation reduces considerably and monotonically for assessment periods of three years or longer. These estimates also observe strong variations of self-citation across disciplines. However, they record the greatest number of self-citation amongst least cited articles in peer-reviewed journals. In a follow up study, Fowler and Aksnes (2007) find strong evidence that self-citation can increase citation from others. Hence the causality of self-citation in citation success is complex and available evidence inconclusive.

Descriptive statistics of the long-term behaviour for aggregate citation success, peer-reviewed, and online working papers suggested that citation success reached its highest point seven years after publication (with the average age in the sample being 7 years old, st. dev. of 4.1, mode and median equal to 1). We also noted that 19 of the top 25 cited items were published before 2005, and only six out of the top 25 cited items were published after 2005. This suggested that the longer a paper has been around, the greater the possibility of having an impact and hence the significance of this variable in the regression. Indeed, there was an attempt to control this effect under the idea that well-established authors have had greater chance to accrue citations than recent graduates. But efforts to introduce a proxy to the years of service or actual age of the authors at the time of publication was futile as such information was not readily available on Internet profiles.

Descriptive statistics also suggested there was an increase in the number of online working papers since 2006. But there was only a 5% chance to find an online working paper for the average peer-reviewed article in the sample. The recent rise in online items helps to explain the low overlap between online and peer-reviewed observed before (i.e. 56 out of the 1109 items) as well as the poor performance of these variables in equations 7 and 8.

It was also noted that of the 1109 items in the sample, most were written in Spanish (667 items or 60%) while 442 (40%) were written in other medium (mainly English). Yet most items in Spanish had zero citations. Indeed, that was the case for 579 papers (52% of all papers in the sample). Here thus lies the explanation for the lack of statistical significance of the language variable in equation 9.

The constant of the regression was negative yet strongly significant for all the nine formulations of the model. The reason for this lies behind the fact that 91% of all items in the sample had a cumulative frequency of less than nine citations.

It was also noted that there were 786 items written by a single author and these represented 70% of the sample, while 323 items were authored by two or more persons and represented only 30% of the sample. Yet in spite of this apparent lower proportion of multi-authored papers, the strong showing of the number of the ‘authors’ variable across all specifications of the regression suggested that collaboration can have a positive impact. As noted above, gender had no impact in any of the specifications.19

Only a small number of authors were registered in RePEc as only 137 papers (12% of the total) had contributors who were amongst the 33,892 persons registered in RePEc. But consistently with the rankings of the latter, 52 papers (5%) resulted from contributions by RePEc's top ranking authors. Results in equations 5 and 6 showed statistical significance for, respectively, dichotomous variables relating to one of the authors being register in RePEc and for those within the top five percent of RePEc's authors. The causality here is not clear because one would expect a highly cited author to be within the top of RePEc but at the same time, an online presence through RePEc can help showcase people's work and thus contribute to citation success. Indeed, overall behaviour of citations success in our sample observes (to the naked eye) significantly lower values that those reported by systematic studies of international peer-reviewed journals (such as Di Vaio et al., 2012).

We noted that only 19 of the 53 outlets in the sample were indexed by the Social Science Citation Index (averaging 1.02 impact factor) and 20 outlets were found in Scopus (averaging 0.22). Also that both Scopus and the Social Science Citation Index exclude outlets we labelled ‘domestic’. However and as shown in formulations 2–5 in Table 6, neither of the two ‘ad hoc’ measures of output quality were found to have statistical significance when ascertaining citation success. Thus suggesting the importance of publishing in international outlets to reach a wide audience.

To conclude, measuring the quality of research through citation success or impact factors is subject to several well-known weaknesses (Anderson et al., 2001; Vanclay, 2012). But in spite of limitations and trickery, there are clear publication strategies emerging from our results, such as the advantages of targeting international, multidisciplinary outlets. Our results also call for more collaborative work. Indeed according to our results, collaboration and particularly that with non-residents can have a significant positive impact in terms of citation success. This as authors based in foreign institutions consistently generated higher average value of citation per item than those we identified within Spanish domestic institutions. Our results not only suggested the importance of broadening international co-operation but also pointed to a small number of individuals accruing a large proportion of citations as well as the need of increasing gender diversity. But as noted, conclusions about authors’ productivity should be taken with caution given the limitations introduced by the selection criteria.

Our results also suggest that citation success is not immediate as it can take up to seven years to reach its peak. To the best of our knowledge this result is novel and calls for further research of similar behaviour of long-term citation success within nearby disciplines (such as regional economics or business and management).

Germane to this article is the role of online publications on citation success. Online publications seem to have grown in importance only in the five to six years prior to 2011. Online publishing thus seems to be a rather recent phenomenon and its overall impact on citation success is still debatable. This is not to negate its importance. Rather, future research to assess the long-term importance of online publishing will perhaps require a different formulation to that adopted in our study.

Finally, statistical analysis gives greater weight to international outlets for citation success and, in turn, this seems to reinforce the perceived importance of a small number of outlets as being ‘world elite’. However, in our view a well-balanced research publications strategy should not disregard the importance of including ‘domestic’ journals. They might not be characterised by publishing leading, original research but they certainly have an audience. Moreover, in the case of the business and economic history of Spain, this audience spreads out through Latin America. In other words, for this area of knowledge, communication of research results in a medium other than English seems important for citation success and hints to the role of Spanish academic circles as intermediaries between Anglo-Saxon and Latin American research.

FundingBolsa de viaje/travel grant.

Fundación Emilio Soldevilla para la Investigación y el Desarrollo en Economía de la Empresa

We appreciate helpful comments and encouragement from anonymous referees, Francisco Comín, Iñaki Iriarte, José Miguel Martínez Carrión, José Luis García Ruíz, Rafael Dobado, Mar Rubio, Jesús María Valdaliso, Carles Maixé, Chris Colvin, Dan Boggart and participants at staff presentations in the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Universidad del País Vasco, University of California – Irvine, FRESH (Edinburgh, 2013) as well as a travel grant from Fundación Emilio Soldevilla para la Investigación y el Desarrollo en Economía de la Empresa. The usual caveats apply.

Sardá-Dexeus (1947) is widely considered as the first Spanish contribution published in a top international journal and more so with an article in economic history. However and according to Bagues (2012), Salvador Barberá was the first Spanish resident author to publish in a top-five ranked journal by ISI Web of Science in 1977. Regardless of this debate, the 25 years since 1987 saw an increase to an accumulated 180 contributions in Web of Science.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Research_Papers_in_Economics (accessed January 4, 2014).

The search tool is readily available at http://econpapers.repec.org/scripts/search/search.asp?pg=-1;nep=nephis and the archives since 1999 are available at http://econpapers.repec.org/scripts/nep.pf?list=nephis (both accessed January 4, 2014). Earlier archives are stored behind a password protected site and available to bonafide researchers by contacting Thomas Krichel (krichel@openlib.org) on a first instance.

Searches terms also included España, español, española as well as specific regions (such as Castilla, Castile, Cataluña, Catalunya and Catalonia). But the latter failed to increase substantially the number of online working papers.

Two key differences between RePEc and SSRN were, first, that the former stores hyperlinks (URL) to research outputs while the latter stored actual PDF documents. Second, SSRN offered limited searches of title, abstract and keyword but would not distinguish between different types of research outputs. Querying SSRN thus returned a mix of working papers and journal articles from which the former were manually extracted.

The journals were: Annales: Histoire, Sciences Sociales; Australian Economic History Review; Cliometrica: Journal of Historical Economics and Econometric History; Economic History Review; European Review of Economic History; Explorations in Economic History; Indian Economic and Social History Review; Irish Economic and Social History; JahrbuchfürWirtschaftsgeschichte; Journal of Economic History; Revista de Historia Económica/Journal of Iberian and Latin American Economic History; Rivista di Storia Economica; Scandinavian Economic History Review.

aehe@listserv.rediris.eshist_empresa@listserv.rediris.es.

h-mexico@servidor.unam.mx and http://www.h-net.org/∼latam/.

http://dialnet.unirioja.es/ and http://www.scielo.org.mx.

Revista de Historia Industrial (176 items, 20% of 864 outputs in peer reviewed journals); Revista de Historia Económica/Journal of Iberian and Latin American Studies (124, 14%); Papeles de Economía Española (109, 13%); Historia Agraria (73, 8%); Investigaciones de Historia Económica (58, 7%); De Computis "Revista Española de Historia de la Contabilidad (47, 5%); Business History (28, 3%); Journal of European Economic History (22, 3%); Economic History Review (20, 2%); América Latina en la Historia Económica (19, 2%); Historia Mexicana (19, 2%): European Review of Economic History (18, 2%); Revista Española de Financiación y Contabilidad (15, 2%); Explorations in Economic History (13, 2%); Journal of Economic History (11, 1%); Financial History Review (10, 1%); Accounting History (9, 1%); Accounting History Review (formerly Accounting, Business & Financial History, 9, 1%); Accounting Historians Journal (7, 1%); Business History Review (7, 1%); Entreprises et Histoire (6, 1%); Journal of Latin American Studies (6, 1%). There were 31 journals with 4 or less items each (adding to 58 items or 7% of total outputs in peer reviewed journals): Abacus; Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal; Accounting, Organizations and Society; Australian Economic History Review; Business & Economic History; Canadian Journal of Latin American & Caribbean Studies; Cliometrica; Critical Perspectives on Accounting; Economics & Human Biology; Enterprise and Society; Essays in Economic & Business History; European Business Organization Law Review; Handbooks of Management Accounting Research; Hispanic American Historical Review; Historia Contemporanea; Industrial and Corporate Change; International Journal of Commons; Journal of Accounting and Public Policy; Journal of Business Ethics; Journal of Economic Issues; Journal of Management History; Journal of Policy Modelling; Journal of the European Economic Association; Journal of Wine Research; Latin American Business Review; Research in Economic History; REVESCO. Revista de Estudios Cooperativos; Rivista di Storia Economica; Scandinavian Economic History Review; The Economic Journal.

See further http://ideas.repec.org/top/top.person.all.html.

Note that here there is no distinction between contributions to single and multiple authored items, all having the same weight.

Free to download outlets were: America Latina en la Historia Económica, Revista Española de Financiación y Contabilidad, Revesco – Revista de Estudios Cooperativos, Journal of Business Ethics, Investigaciones de Historia Económica, International Journal of Commons, Historia Contemporánea, Essays in Economic and Business History, De Computis, Business and Economic History; and Accounting Historians Journal (the latter only for items published between 1974 and 2009).

There is a small discrepancy between Fig. 3 and Table 4 in the value for the top cited item. This responded to measurements in Harzing's Publish or Perish being susceptible the date in which they are accrued.

ABS Academic Journal Quality Guide, accessed from http://www.associationofbusinessschools.org/content/abs-academic-journal-quality-guide (accessed January 3, 2013).

ERA 2012 Journal List, accessed from http://www.arc.gov.au/era/era_2012/era_journal_list.htm (accessed January 3, 2013).

Índice de Impacto de las revistas españolas de ciencias sociales (economía). Accessed from http://ec3.ugr.es/in-recs/acumulados/Economia-3.htm (accessed January 3, 2013).

http://www10.gencat.cat/agaur_web/AppJava/castellano/a_info.jsp?contingut=carhus_2010 (accessed January 3, 2013).

Bosquet and Combes (2012) observe similar results regarding gender and co-authors for research in economics by French scholars.