The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) have defined audit as “a quality improvement process that seeks to improve patient care and outcomes through systematic review of care against explicit criteria and the implementation of change”.1 As such it plays an integral role in ensuring the delivery of high-quality patient care and forms a cornerstone of clinical governance within surgery, with the General Medical Council (GMC) advising all doctors ‘must take part in regular and systematic medical and clinical audit’.2 There has been criticism of the practice of audit within hospitals. To investigate the efficacy of clinical audit we analysed the audit practices within the orthopaedic department of Wythenshawe Hospital, a large teaching hospital in the North West deanery UK, over a 5-year period.

Clinical audit is formed of six prescript stages, making up the audit cycle. These stages are: (1) identifying a problem, (2) identifying set standards, (3) measuring current practice, (4) comparing current practice against set standards, (5) implementing change, (6) re-measuring practice.1

Implementing change necessitates presenting findings and agreeing recommendations. Recommendations should meet the SMART criteria, being Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Time-Bound.3 Meeting SMART criteria provides a framework to reach clearly defined audit goals. An effective audit must show completion of the audit cycle, allowing for demonstration of change to practice.4 Completing this cycle has previously demonstrated positive results in orthopaedics.5 Demonstrating sustainability relies upon repeating the audit cycle at regular intervals.

There has been criticism of the practice of audit within hospitals. Previous papers have suggested that many do not have clear objectives, are not set against recognised standards and that the proportion of completed audit cycles falls far below the recommended 100%.6–8 Furthermore, it is thought that clinician time and hospital funding committed to the process often has a negative impact on doctor's clinical time and does not always show improvement to the standard of patient care.9

We retrospectively reviewed all Trauma and Orthopaedic projects registered with the audit department at Wythenshawe Hospital between 2013 and 2018. Projects that satisfied a minimum of 3/6 stages of the audit cycle were included, with presented work that did not meet the criteria excluded. Audit meeting minutes and audit presentations were scrutinised. Audits were categorised into ‘partial’ (satisfying 3/6 stages of audit cycle), ‘full’ (satisfying 5/6 stages) or ‘re-audit’ (satisfying 6/6 stages).8 We reviewed the audit action plans, assessed their quality against the SMART objective setting criteria and determined departmental trends for re-audit.

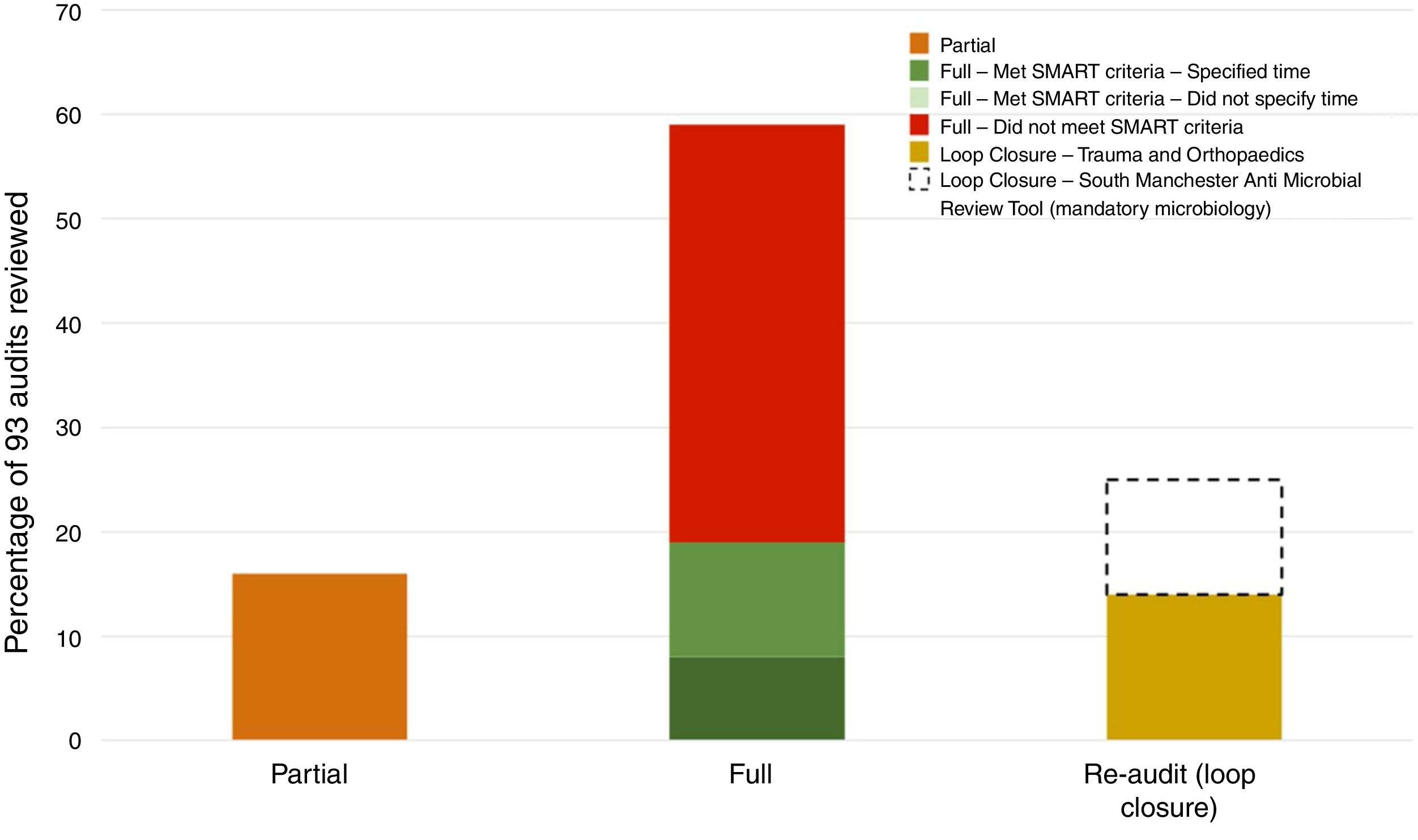

Over a 5-year period there were 129 projects presented at the quarterly audit meetings. 36 were excluded, as they failed to meet the definition of clinical audit. These included case reports, research projects and teaching sessions. The most common category for audit was ‘neck of femur fractures’ and ‘other’ (18% each), with ‘spine’ having the lowest number (4%). Of the 93 audits reviewed (see Fig. 1):

- •

15 (16%) were only partially completed, either failing to make comparison between the identified standards and observed practice or failing to agree recommendations for change to clinical practice.

- •

55 (59%) were ‘full’ audits, making recommendations and yet failing to demonstrate a change to clinical practice. Only 18 (33%) of these audits made recommendations that met the criteria for SMART objective setting, with a clear plan to re-audit in the future.

- •

23 (25%) could be classified as ‘re-audits’, completing all six stages. However, of these 23 re-audits, 10 were of the same audit repeated at regular intervals over a three-year period (the South Manchester Antimicrobial Review Tool, which had been completed as part of the microbiology department's mandatory auditing protocol) and of the remaining 13 re-audits only 2 made subsequent recommendation for long-term monitoring.

Our department performed an average of 18.6 audits each year over a 5-year period, higher than that of previously documented studies.6,7 We found that of the audits analysed 59% were deemed ‘full’ audits, again higher than that reported by other groups.9 Only 33% made recommendations that met SMART criteria for objective setting. The remainder failed to outline a robust strategy to achieve and monitor change. As such, few of these progressed to loop closure.

The explanation for poor audit practice is multifactorial. With an ever-increasing workload medical staff are often reluctant to commit time to clinical audit, which can be perceived as a tick box exercise. Furthermore, junior staff members feel unsupervised and unsupported, negatively impacting on the quality of audit.10 Regular rotations and changes of junior staff mean that audit follow-up can be neglected unless new staff members are made aware of what is required of them.

To improve the quality and efficacy of clinical audit all junior staff should be educated on local audit practices upon induction to a new rotation/department9. Doing so will promote early engagement.

Advances in information technology should be utilised such to improve ease of audit registration, as well as provide access to past audits proposals, data collection proformas and recommendations.9

Categorising audits in terms of priority will ensure that important clinical concerns are monitored, whilst using the SMART criteria for objective setting to agree an action plan will clarify how and when this monitoring is to take place. Audit supervisors and departmental audit leads must adopt a more hands-on approach to guide juniors, with previous studies showing projects led by consultants show a higher proportion of audit completion.9 Audit departments should be encouraged to audit their outcomes annually, with findings presented and discussed at local directorate meetings.

Audit is an important component of health care service quality control and improvement and if performed well has been shown to improve medical practice.4,5 For this benefit to be achieved and monitored it is essential that the audit cycle is completed. We found that in the trauma and orthopaedic department of a large teaching hospital this was often not the case, a finding not isolated to the studied hospital.6–8 We suggest that improvement requires a structured approach, aiming to increase the audit quality and completion rate, improving patient care and ensuring staff time and trust finances are used efficiently.