The current study aimed to assess the reporting quality of the clinical practice guidelines/consensuses on metastatic colorectal cancer based on the Reporting Items for Practice Guidelines in HealThcare (RIGHT) checklist.

MethodsWe searched China National Knowledge Infrastructure, VIP database, Wanfang Data, Chinese Biological Literature Service System, PubMed, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, Elsevier clinicalkey, BMJ Database, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, World Health Organization Network and other websites. We collected clinical practice guidelines/consensuses on metastatic colorectal cancer with published between 1 January 2017 and 1 April 2021 after release of the RIGHT checklist. Two reviewers extracted the basic information independently and conducted a RIGHT evaluation.

ResultsEighteen guidelines/consensuses were included, 10 from China and 8 from other countries. The average reporting rate was 74.1%±11.2%. Thirteen items had 100% reporting rate, and the reporting rate for items No. 16 (11.1%), 17 (16.7%) and 18b (22.2%) was low. Basic information had the highest reporting rate (100%), whereas review and quality assurance had the lowest (13.9%). The average reporting rate of guidelines/consensuses published in other countries was higher than in China [p=0.005; odds ration (OR) 1.17, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.07–1.28]. The average reporting rate of the guidelines was higher than that of the consensus statements (p<0.001; OR 1.20, 95% CI 1.10–1.31). The reporting rates of guidelines/consensuses focused on whole body (79.0%±12.7%) were higher than local organ (69.2%±7.3%) metastases (p=0.005; OR 1.14, 95% CI 1.04–1.25).

ConclusionsThe quality of reporting using the RIGHT checklist varied among the guidelines/consensuses on metastatic colorectal cancer. Low-quality items were external review and quality assurance. Developers of guidelines/consensuses should aim to improve the reporting quality in the future.

Evaluar la calidad de la presentación de informes sobre las directrices de la práctica clínica / consenso para el cáncer colorrectal metastásico, sobre la base de la lista de artículos de la Guía de la práctica médica (RIGHT).

MétodosSe recuperaron la infraestructura nacional de conocimientos de China, la base de datos VIP, los datos wanfang, el sistema de servicios de documentación biológica de China, Pubmed, Science Net, Science Direct, Elsevier Clinical Key, BMJ Database, embase, Cochrane Library y la red de la OMS. Se recopilaron las directrices de práctica clínica / consenso para el cáncer colorrectal metastásico, publicadas del 1 de enero de 2017 al 1 de abril de 2021. Los dos revisores extrajeron la información básica de forma independiente y la evaluaron RIGHT.

ResultadosIncluye 18 directrices / consenso, 10 de China y 8 de otros países. La tasa media de presentación de informes fue del 74.1% ± 11.2%. La tasa de presentación de informes para 13 ítems fue del 100%, mientras que la tasa de presentación de informes para los ítems 16 (11.1%), 17 (16.7%) y 18b (22.2%) fue baja. La tasa de presentación de informes sobre la información básica fue la más alta (100%), mientras que la tasa de examen y garantía de calidad fue la más baja (13.9%). La tasa media de presentación de informes de las directrices / consenso publicadas por otros países fue superior a la de China [P = 0.005; relación de razón (RR) 1.17; intervalo de confianza del 95% (IC) 1.07 - 1.28]. La tasa media de presentación de informes de las directrices fue superior a la Declaración de consenso (P< 0.001; RR 1.20, IC del 95% 1.10 - 1.31). Las tasas de notificación de orientación / consenso para la atención sistémica (79.0% ± 12.7%) fueron mayores que las de metástasis de órganos locales (69.2% ± 7.3%) (P = 0.005; RR 1.14, IC 95%: 1.04 - 1.25).

ConclusiónLa calidad de los informes sobre el uso de la lista de verificación RIGHT es diferente en las directrices / consenso para el cáncer colorrectal metastásico. Los proyectos de baja calidad incluyen exámenes externos y garantía de calidad. Los encargados de elaborar las directrices y el consenso deberían trabajar para mejorar la calidad de los futuros informes.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer worldwide. In 2020, there were 1931590 patients with CRC and 935173 deaths reported, which makes CRC second largest cause of cancer-related death.1 About 20% of CRC patients have metastasis at the time of diagnosis, and >50% have metastasis during the course of the disease.2 The incidence and mortality rate of CRC are decreasing in some developed countries, whereas the number of cases and deaths has increased in some Eastern European, South American and Asia countries.3 The main metastatic site of CRC is the liver, which is found in ∼30% of patients and accounts for two-thirds of deaths.4 Colorectal metastases to other parts of the body are rare, including lung, peritoneum, pelvic lymph nodes, bone, brain and ovaries, and often coexist with liver metastases. In the past decade, the clinical prognosis of patients with CRC has been significantly improved, especially for metastatic CRC (mCRC). The median overall survival of patients with mCRC is estimated to be ∼30 months, which is more than twice that 20 years ago.5 This result may be related to changes in treatment and management plans, such as providing closer follow-up of precancerous lesions, technological advances, and more timely and effective treatment (especially second-line treatment). An increasing number of patients undergo resection and ablation treatment, leading to higher recurrence free survival and better quality of life. Therefore, the clinical practice criteria for mCRC are critical.

Clinical practice guidelines/consensuses are statements of systematic development to help doctors and patients determine the appropriate Healthcare plan for specific clinical circumstances.6 Whether or not the guidelines/consensuses are standardized is an important factor in deciding whether they can be popularized and implemented well.7 Appraisal of Guidelines for REsearch and Evaluation II (AGREE II)8 and Reporting Items for Practice Guidelines in HealThcare (RIGHT)9 tools are adopted internationally in systematic evaluation for health policy, public health, and clinical practice guidelines/consensuses.10 The RIGHT checklist is an indicator and method developed by an international working group to evaluate the reporting quality of guidelines/consensuses. It assists developers in reporting guidelines, supports journal editors, and peer reviewers when considering guideline reports, and helps health-care practitioners understand and implement a guideline. The checklist became a powerful tool for guideline evaluation different from AGREE II, a tool to assess the methodological rigor and transparency in which a practice guideline is developed and can be used to guide their development. Based on the RIGHT checklist, we evaluated the reporting quality of the current Chinese and international clinical practice guidelines/consensuses on mCRC form 2017 onwards. The purpose was to assist with formulation of comprehensive and standardized guidelines/consensuses to enable progress and development of the clinical practice for mCRC.

Materials and methodsStudy designThis study comprised a review of mCRC clinical practice guidelines/consensuses using the RIGHT checklist and was performed in accordance with the guidelines for reporting systematic reviews.11 All analyses were based on previous published studies, thus no ethical approval and patient consent were required.

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaWe included guidelines/consensuses on diagnosis and/or treatment of mCRC. We excluded old version of guidelines/consensuses, those that did not focus solely on mCRC, documents in the process of development, and repeated issues.

Search strategyWe searched China National Knowledge Infrastructure, VIP database, Wanfang Data, Chinese Biological Literature Service System, PubMed, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, Elsevier clinicalkey, BMJ Database, Embase, Cochrane Library, World Health Organization Network, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and Guidelines International Collaboration Network to collect clinical practice guidelines/consensuses on mCRC published in China and abroad between 1 January 2017 to 1 April 2021. The search strategy used the terms ‘colorectal neoplasms’ or ‘colorectal cancer’ and ‘metastatic tumor’ or ‘metastases’ and ‘guideline’ or ‘consensus’ or ‘recommendation’. We included guidelines/consensuses published in medical journals or websites in English or Chinese language. Two authors (WL and YL) conducted independent screening and cross-checking based on title, abstract, and full text, and resolved any differences through discussion.

Data extraction and reporting quality assessmentWe extracted and described the basic information of the literature retrieved, including the title, guidelines/consensuses, country, formulation agency, release time, release version, and metastatic sites of CRC. Before evaluating reporting quality, it was necessary to train the two researchers about the RIGHT checklist and ensure each researcher had the same understanding of the listed items. Each checklist item was evaluated by ‘reported’ and ‘not reported’. ‘Reported’ referred to the relevant information of the item presented. ‘Not reported’ referred to the relevant information of the item not presented. The RIGHT checklist includes 7 major sections and 35 specific items. Two authors (WL and YL) independently extracted and cross-checked data, and resolved any differences through discussion.

Data analysisNoteExpress software (Beijing, China) was used for literature management. Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA, USA) was used to record whether each list item was reported. The reported percentage of each item was summarized and calculated. Other basic information of the guidelines/consensuses was analyzed by subgroup, such as from China or other countries, guidelines or consensus statements, whole body or local metastasis. SPSS version 20.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis. The Crosstabs of descriptive statistics were used to calculate odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI).

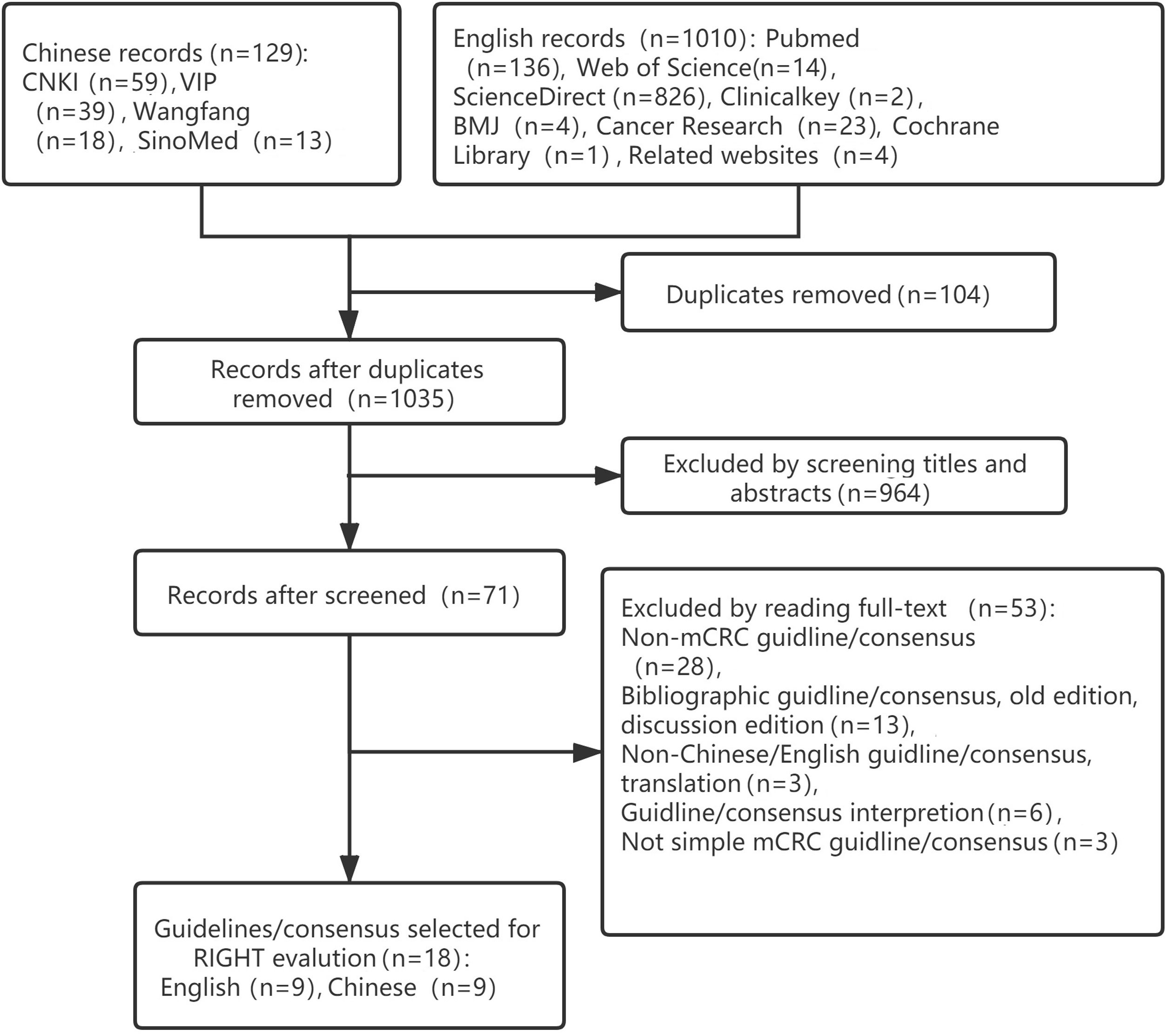

ResultsBasic informationA total of 1139 potentially relevant articles were identified, including 129 in Chinese and 1010 in English: 964 were excluded after title and abstract screening. The remaining 71 were retrieved and full texts were read, resulting in 18 guidelines that met the inclusion criteria. The literature screening process is shown in Fig. 1.

Eighteen clinical practice guidelines/consensuses on mCRC were included, of which 6 (33.3%) were guidelines and 12 (66.7%) were consensus statements. Six articles (33.3%) were published in 2020 and 5 (27.8%) in 2019. Ten articles (55.6%) were published in China and 8 (44.4%) in other countries. Most guidelines/consensuses were the initial version, and only 2 (11.1%) were revised versions. Sixteen (88.9%) guidelines/consensuses were published by a medical society or association. In terms of metastatic sites of CRC, 9 (50%) guidelines/consensuses focused on all parts of the body, 3 (16.7%) on the liver, and 6 (33.3%) on other organs (Table 1).

Characteristics of guidelines/consensuses on mCRC.

| Title of guidelines/consensuses | Guideline/consensus | Year of publication | Country/region | Version | Society and association | Metastatic site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pan-Asian adapted ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer; A JSMO-ESMO initiative endorsed by CSCO, KACO, MOS, SSO and TOS12 | Guideline | 2017 | Pan-Asian | Initial | Yes | Whole body |

| The predictive effect of primary tumor location in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: a Canadian consensus statement13 | Consensus | 2017 | Canada | Initial | Yes | Whole body |

| Consensus statement on essential patient characteristics in systemic treatment trials for metastatic colorectal cancer: Supported by the ARCAD Group14 | Consensus | 2018 | Worldwide | Initial | Yes | Whole body |

| Treatment of Patients With Late-Stage Colorectal Cancer: ASCO Resource-Stratified Guideline15 | Guideline | 2020 | America | Initial | Yes | Whole body |

| Consensus on management of metastatic colorectal cancer in Central America and the Caribbean: San José, Costa Rica, August 201616 | Consensus | 2018 | Central America/Caribbean | Initial | No | Whole body |

| SEOM clinical guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer (2018)17 | Guideline | 2018 | Spain | Initial | Yes | Whole body |

| Multidisciplinary management of liver metastases in patients with colorectal cancer: a consensus of SEOM, AEC, SEOR, SERVEI, and SEMNIM18 | Consensus | 2019 | Spain | Initial | Yes | Liver |

| Metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): French intergroup clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatments and follow-up (SNFGE, FFCD, GERCOR, UNICANCER, SFCD, SFED, SFRO, SFR)19 | Guideline | 2019 | France | Initial | Yes | Whole body |

| Taiwan Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (TSCRS) Consensus for Cytoreduction Selection in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer20 | Consensus | 2020 | Taiwan, China | Initial | Yes | Whole body |

| Expert consensus on multidisciplinary treatment of lung metastases from colorectal cancer (2018 Edition)21 | Consensus | 2018 | China | Initial | Yes | Lung |

| Chinese expert consensus for prophylactic and therapeutic intraperitoneal medication for peritoneal metastases from colorectal cancer (2019 edition)22 | Consensus | 2019 | China | Initial | Yes | Peritoneum |

| Guidelines for simultaneous laparoscopic/robotic resection of colorectal cancer with liver metastases (revised in 2017)23 | Guideline | 2017 | China | Update | Yes | Liver |

| China guideline for diagnosis and comprehensive treatment of colorectal liver metastases (2020 edition)24 | Guideline | 2020 | China | Update | Yes | Liver |

| Chinese experts consensus on multidisciplinary treatment of bone metastases from colorectal cancer (2020 version)25 | Consensus | 2020 | China | Initial | Yes | Bone |

| Chinese experts consensus on the management of ovarian metastases from colorectal cancer (2020 version)26 | Consensus | 2020 | China | Initial | Yes | Ovary |

| Chinese experts consensus on multidisciplinary treatment of brain metastases from colorectal cancer (2020 version)27 | Consensus | 2020 | China | Initial | Yes | Brain |

| Chinese expert consensus on the diagnosis and treatment for lateral lymph node metastasis of rectal cancer (2019 edition)28 | Consensus | 2019 | China | Initial | Yes | Lateral lymph node |

| Systematic review and expert consensus on second-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer in China29 | Consensus | 2019 | China | Initial | No | Whole body |

mCRC, metastatic colorectal cancer; ESMO, European Society for Medical Oncology; JSMO, Japanese Society of Medical Oncology; CSCO, Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology; KACO, Korean Association for Clinical Oncology; MOS, Malaysian Oncological Society; SSO, Singapore Society of Oncology; TOS, Taiwan Oncology Society; ARCAD, Analysis and Research in Cancers of the Digestive system; ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology; SEOM, Spanish Society of Medical Oncology; AEC, Spanish Association of Surgeons; SEOR, Spanish Society of Radiation Oncology; SERVEI, Spanish Society of Vascular and Interventional Radiology; SEMNIM, Spanish Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging; SNFGE, French Society of Gastroenterology; FFCD, French Federation of Digestive Oncology; GERCOR, Groupe Coopérateur Multidisciplinaire en Oncologie; SFCD, French Society of Digestive Surgery; SFED, French Society of Digestive Endoscopy; SFRO, French Society of Radiation Oncology; SFR, French Society for Rheumatology; TSCRS, Taiwan Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons.

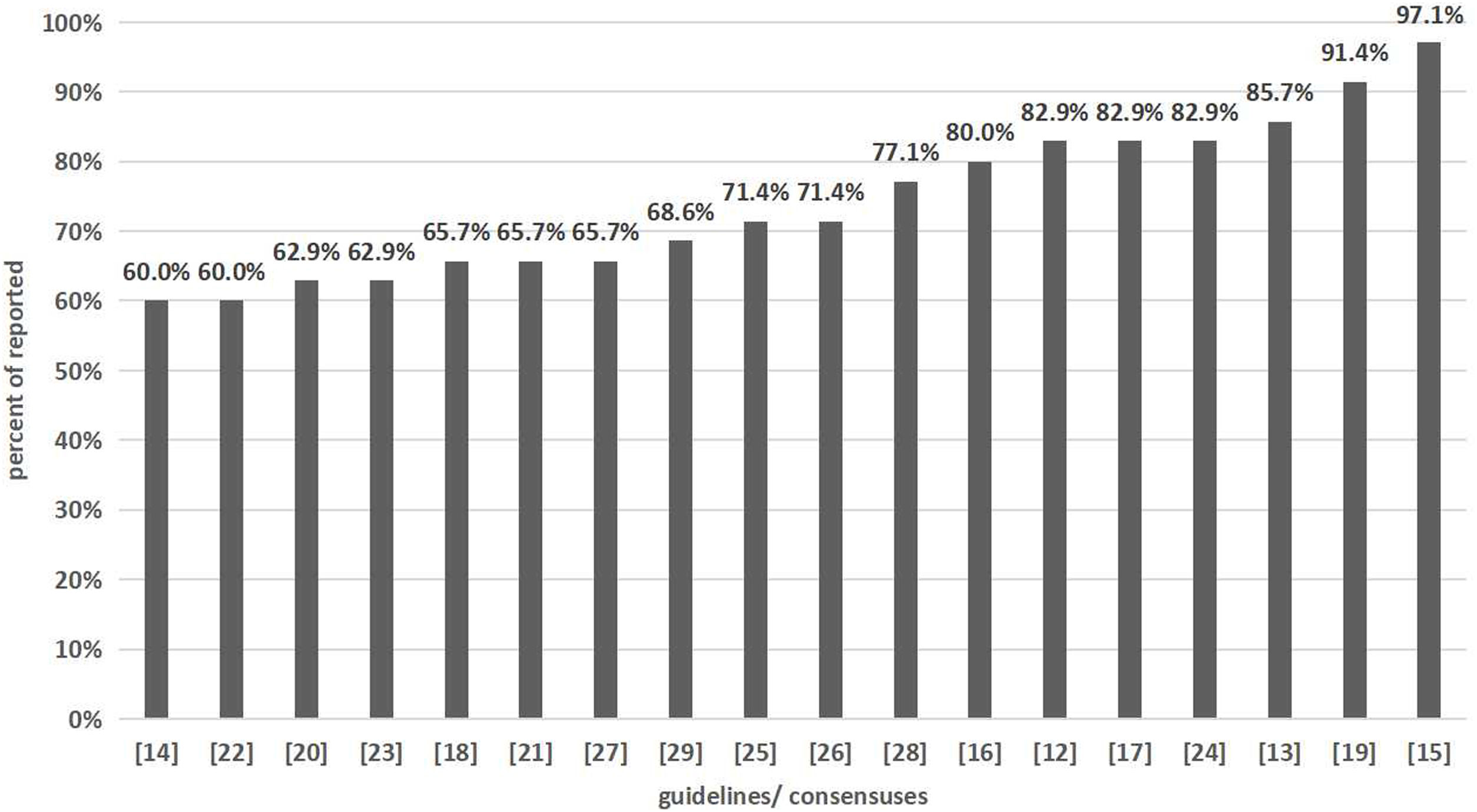

Based on the 35 items of the RIGHT checklist, the average reporting rate of the 18 clinical practice guidelines/consensuses on mCRC was 74.1%±11.2%. The reporting rate of 13 items was 100%, and items No. 16 (11.1%), 17 (16.7%), and 18b (22.2%) was low. According to the report of each section, the highest reporting rate was for basic information (100%), and the lowest was for review and quality assurance (13.9%) (Table 2). We assessed each item according to the standard and calculated the percentage of fully reported items (Fig. 2).

Reporting rate of 35-item RIGHT checklist for clinical practice guidelines/consensuses on mCRC.

| Section | Topic | Number | Item | Reported (n) | Unreported (n) | Average reporting rate (%) | Total reporting rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic information | Title/subtitle | 1a | Identify the report as a guideline, that is, with ‘guideline(s)’ or ‘recommendation(s)’ in the title. | 18 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| 1b | Describe the year of publication of the guideline. | 18 | 0 | 100 | |||

| 1c | Describe the focus of the guideline, such as screening, diagnosis, treatment management, prevention or others. | 18 | 0 | 100 | |||

| Executive summary | 2 | Provide a summary of the recommendations contained in the guideline. | 18 | 0 | 100 | ||

| Abbreviations and acronyms | 3 | Define new or key terms, and provide a list of abbreviations and acronyms if applicable. | 18 | 0 | 100 | ||

| Corresponding developer | 4 | Identify at least one corresponding developer or author who can be contacted about the guideline. | 18 | 0 | 100 | ||

| Background | Brief description of the health problem(s) | 5 | Describe the basis epidemiology of the problem, such as the prevalence/incidence, morbidity, mortality and burden (including financial) resulting from the problem. | 18 | 0 | 100 | 88.9 |

| Aim(s) of guideline and specific objectives | 6 | Describe the aim(s) of the guideline and specific objectives, such as improvements in health indicators, quality of life or cost saving. | 18 | 0 | 100 | ||

| Target population(s) | 7a | Describe the primary population(s) that is affected by the recommendation(s) in the guideline. | 18 | 0 | 100 | ||

| 7b | Describe any subgroups that are given special consideration in the guideline. | 17 | 1 | 94.4 | |||

| End users and settings | 8a | Describe the intended primary users of the guideline and other potential users of the guideline. | 18 | 0 | 100 | ||

| 8b | Describe the setting(s) for which the guideline is intended, such as primary care, low-income and middle-income countries, or inpatient facilities. | 9 | 9 | 50 | |||

| Guideline development groups | 9a | Describe how all contributors to the guideline development were selected and their roles and responsibilities. | 12 | 6 | 66.7 | ||

| 9b | List all individuals involved in developing the guideline, including their title, role(s) and institutional affiliation(s). | 18 | 0 | 100 | |||

| Evidence | Health care questions | 10a | State the key questions that were the basis for the recommendations in PICO (population, intervention, comparator and outcome) or other format as appropriate. | 18 | 0 | 100 | 53.3 |

| 10b | Indicate how the outcomes were selected and sorted. | 9 | 9 | 50 | |||

| Systematic reviews | 11a | Indicate whether the guideline is based on new systematic reviews done specifically for this guideline or whether existing systematic reviews were used. | 8 | 10 | 44.4 | ||

| 11b | If the guideline developers used existing systematic reviews, reference these and describe how those reviews were identified and assessed and whether they were updated. | 7 | 11 | 38.9 | |||

| Assessment of the certainty of the body of evidence | 12 | Describe the approach used to assess the certainty of the body of evidence. | 6 | 12 | 33.3 | ||

| Recommendations | Recommendations | 13a | Provide clear, precise and actionable recommendations. | 17 | 1 | 94.4 | 82.5 |

| 13b | Present separate recommendations for important subgroups if the evidence suggests that there are important differences in factors influencing recommendations, particularly the balance of benefits and harms across subgroups. | 17 | 1 | 94.4 | |||

| 13c | Indicate the strength of recommendations and the certainty of the supporting evidence. | 8 | 10 | 44.4 | |||

| Rationale/explanation for recommendations | 14a | Describe whether values and preferences of the target population(s) were considered in the formulation of each recommendation. | 17 | 1 | 94.4 | ||

| 14b | Describe whether cost and resource implications were considered in the formulation of recommendations. | 10 | 8 | 55.6 | |||

| 14c | Describe other factors taken into consideration when formulating the recommendations, such as equity, feasibility and acceptability. | 17 | 1 | 94.4 | |||

| Evidence to decision processes | 15 | Describe the processes and approaches used by the guideline development group to make decisions, particularly the formulation of recommendations. | 18 | 0 | 100 | ||

| Review and quality assurance | External review | 16 | Indicate whether the draft guideline underwent independent review and, if so, how this was executed and comments considered and addressed. | 2 | 16 | 11.1 | 13.9 |

| Quality assurance | 17 | Indicate whether the guideline was subjected to a quality assurance process. | 3 | 15 | 16.7 | ||

| Funding and declaration and management of interests | Funding source(s) and role(s) of the funder | 18a | Describe the specific sources of funding for all stages of guideline development. | 16 | 2 | 88.9 | 47.2 |

| 18b | Describe the role of funder(s) in the different stages of guideline development and in the dissemination and implementation of the recommendations. | 4 | 14 | 22.2 | |||

| Declaration and management of interests | 19a | Describe what types of conflicts were relevant to guideline development. | 8 | 10 | 44.4 | ||

| 19b | Describe how conflicts of interest were evaluated and managed and how users of the guideline can access the declarations. | 6 | 12 | 33.3 | |||

| Other information | Access | 20 | Describe where the guideline, its appendices and other related documents can be accessed. | 18 | 0 | 100 | 81.5 |

| Suggestions for further research | 21 | Describe the gaps in the evidence and/or provide suggestions for future research. | 18 | 0 | 100 | ||

| Limitations of the guideline | 22 | Describe any limitations in the guideline development process, and indicate how affected the validity of the recommendations. | 8 | 10 | 44.4 | ||

RIGHT, Reporting Items for practice Guidelines in HealThcare; mCRC, metastatic colorectal cancer.

Among the 18 guidelines/consensuses, 8 were from other countries and 10 from China. There was a significant difference in the overall reporting rate between foreign and Chinese guidelines/consensuses (p=0.005; OR 1.17, 95% CI 1.07–1.28), and the average reporting rate of foreign guidelines/consensuses (80.7%±12.4%) was higher than Chinese guidelines/consensuses (68. 9%±7.1%). For item No. 11a, 13c, 19a and 19b, Chinese guidelines/consensuses reporting rates were significantly lower than those of foreign guidelines/consensuses (Supplementary material, Table 3).

Comparison of reporting rates between guidelines and consensus statementsAmong the 18 guidelines/consensuses, 6 were guidelines and 12 were consensuses. The overall reporting rate of clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements on mCRC was significantly different (p<0.001; OR 1.20, 95% CI 1.10–1.31), and the reporting rate of guidelines (83.4%±11.6%) was higher than that of consensus statements (69. 5%±8.0%). In terms of item No. 11a, 11b, 12, 13c and 17, the reporting rate of guidelines was significantly higher than that of consensus statements (Supplementary material, Table 4).

Comparison of guidelines/consensuses reporting rates between whole body and local metastasesAmong the 18 guidelines/consensuses, 9 were focused on widespread metastatic sites and 9 on local organ metastasis. The reporting rates of guidelines/consensuses focused on whole body (79.0%±12.7%) and local organ (69.2%±7.3%) metastases showed a significant difference (p=0.005; OR 1.14, 95% CI 1.04–1.25). In terms of item No. 19b, the reporting rate of guidelines/consensuses focused on whole body was significantly higher than that of local organ (Supplementary material, Table 5).

DiscussionThis study assessed the reporting quality of 18 clinical practice guidelines/consensuses on mCRC since 2017 based on the RIGHT checklist. The best reporting quality achieved a score of 97.1%,15 whereas the worst achieved a score of 60.0%.14,22 Han et al.30 evaluated the reporting quality of practice guidelines on all not just metastatic CRC using the RIGHT checklist, and found that the best reporting quality achieved a score of 71% and the worst achieved a score of 24.1%. The reporting quality in our study was better than that for epilepsy,31 polycystic ovary syndrome,32 and diabetes33 practice guidelines. The average reporting rate (74.1%±11.2%) for all items was higher than that reported by Chinese researchers for CRC screening guidelines/consensuses (61.2%±22.1%).34 The reporting quality of clinical practice guidelines/consensuses in our study was higher than in other studies possibly because we only focused on guidelines/consensuses on mCRC published after 2017.

Among the 18 clinical practice guidelines/consensuses on mCRC, 10 were from China, including 2 guidelines and 8 are consensus statements. The disproportionate number of Chinese papers reflected a preoccupation in China for mCRC. Most Chinese guidelines/consensuses did not describe systematic reviews, strength of recommendations, quality of evidence supporting the recommendations, and the declaration and management of interest. There was a gap in quality between Chinese and foreign guidelines/consensuses on mCRC. A 2017 study35 reported the poor quality of 107 clinical practice guidelines published in Chinese journals, which stated a reporting rate of 34.8%±0.1% indicating that the low quality of clinical practice guidelines in China is an overall problem.

Reporting rate of guidelines was significantly higher than that of consensus statements in describing systematic reviews, assessing the certainty of the body of evidence, the strength of recommendations, and quality assurance. These findings coincide with the viewpoint of Chen Yaolong and other researchers in China.36 Although the widespread view is that expert consensus statements in medicine are of lower quality and influence than guidelines are, users should master the basic methods to evaluate the quality and credibility of both guidelines and consensus statements, to avoid misleading or inappropriate recommendations.37 Therefore, during writing, guidelines and consensus statements should be detailed and fully report the core and key information in accordance with the RIGHT checklist.

Eight articles were reported from China focused on local metastatic sites. We found that the Chinese guidelines/consensuses paid more attention to the diagnosis and treatment of local organ metastasis of CRC, including almost all the common metastatic sites, such as liver, lung, bone, brain, ovary and peritoneum. The survival time of patients with CRC has improved, which may be because of progress in imaging technology that makes local organ metastases easier to detect, for example, the incidence of brain metastasis is significantly higher than before.27 If mCRC is not treated, the prognosis of patients will be adversely affected. Therefore, the guidelines/consensuses compiled by Chinese authors can guide clinical practice, which is worthy of encouragement and approval.

The limitations of this study were as follows. (1) We only included guidelines/consensuses in Chinese or English languages. (2) AGREE II tool has high international authority and the evaluation results are widely recognized, but it focuses more on methodology evaluation and pays less attention to the normative content of the guidelines. The RIGHT checklist is not a report quality evaluation tool of published guidelines/consensuses and it is mainly used to standardize the writing of new guidelines/consensuses. In the future, it is necessary to appraise clinical practice guidelines/consensuses on mCRC by AGREE II tool to assess the methodology quality. (3) Some guidelines/consensuses might have been missed by computerized searches.

The reporting quality varied among the existing clinical practice guidelines/consensuses on mCRC, and the lowest section was review and quality assurance. Future guidelines/consensuses developers should master relevant guideline reporting and evaluation tools, such as the RIGHT checklist, strengthen the standardization of formulation, pay more attention to the details and comprehensiveness of the reporting process, improve the quality of guidelines/consensuses, and promote their function in guiding clinical practice.

Authors’ contributionsWe thank Cathel Kerr, BSc, PhD, from Liwen Bianji (Edanz) (www.liwenbianji.cn/) for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

FundingThis study was supported by No. (2015)160 from Beijing Scholars Program and No. yyqdktbh2020-9 from Beijing Friendship Hospital, Capital Medical University.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.