Defensive medicine (DM) is used when a doctor deviates from good practices to prevent complaints from patients or caregivers. This is a structured phenomenon that may not only affect the physician, but all healthcare personnel. The aim of this review was to determine whether DM is also performed by Non-Medical Health Professionals (NMHP), and the reasons, features, and effects of NMHP-DM.

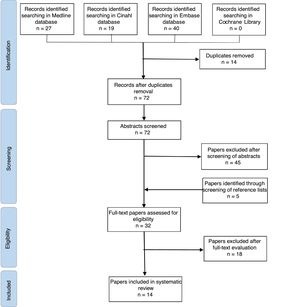

Materials and methodsThe review was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines, and specific inclusion criteria were used to search for relevant documents published up to 12 April 2018 in the main biomedical databases.

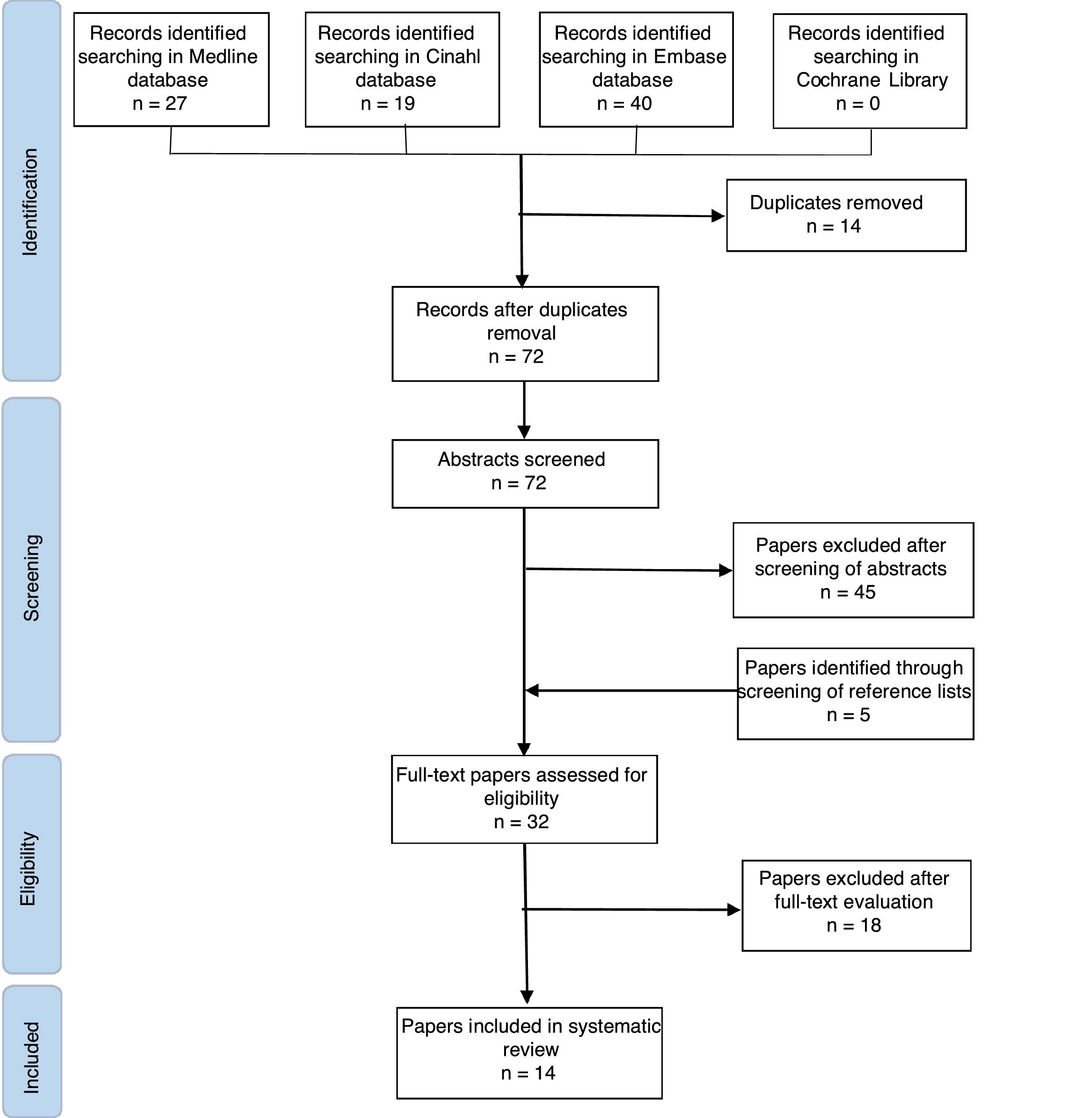

ResultsA total of 91 potentially relevant studies were identified. After the removal of duplicates, 72 studies were screened for eligibility, separately by two of the authors. Finally, 14 qualitative and quantitative studies were considered relevant for the purpose of the present review. These last studies were assessed for their methodological quality.

ConclusionsNMHP-DM is quite similar to DM practiced by doctors, and is mainly caused by fear of litigation. Midwives and nursing personnel practiced both active and passive DM, such as over-investigation, over-treatment, and avoidance of high-risk patients. NMHP-DM could increase risks for patient health, costs, risk of burnout for healthcare employees. Further studies are needed to better understand prevalence and features of NMHP-DM in all health professional fields, in order to apply appropriate preventive strategies to contrast DM among health care personnel.

Se denomina medicina defensiva (MD) a aquella que lleva a cabo un médico cuando se desvía de las buenas prácticas e intenta evitar las quejas de los pacientes o cuidadores. Este es un fenómeno organizado que no solo puede afectar al médico, sino también a todo el personal sanitario. El objetivo de esta revisión fue establecer si otros profesionales sanitarios no médicos (PSNM) también llevan a cabo MD y los motivos, las características y los efectos de la MD de los PSNM.

Materiales y métodosLa revisión se realizó de acuerdo con las directrices de PRISMA y se utilizaron criterios de inclusión específicos para buscar documentos importantes publicados hasta el 12 de abril de 2018 en las principales bases de datos biomédicas.

ResultadosSe identificaron un total de 91 estudios potencialmente importantes. Después de la eliminación de los duplicados, 72 de los estudios se analizaron detenidamente y por separado por dos de los autores. Finalmente, 14 estudios cualitativos y cuantitativos se consideraron importantes para la finalidad de esta revisión. Estos últimos estudios se evaluaron por su calidad metodológica.

ConclusionesLa MD de los PSNM es bastante similar a la MD practicada por los médicos, y se debe principalmente al temor a una demanda. Las comadronas y el personal de enfermería han practicado MD activa y pasiva, como la investigación excesiva, el tratamiento excesivo y la evitación de pacientes de alto riesgo. La MD de los PSNM podría aumentar los riesgos para la salud del paciente, los costes y el riesgo de agotamiento de los empleados sanitarios. Se necesitan estudios adicionales para comprender mejor la incidencia y las características de la MD de los PSNM en todos los campos de profesionales sanitarios a fin de aplicar estrategias preventivas adecuadas para comparar la MD entre el personal sanitario.

Defensive medicine (DM) is defined as a doctors’ deviation from what is considered to be a good practice, to reduce or prevent complaints or criticism from patients or their families1–5 and to avoid financial and psychological losses.2 DM can take two forms: positive and negative. Positive DM includes the supply of care that is unproductive for patients, it occurs when extra tests and procedures are performed primarily to prevent malpractice liability; negative DM takes place when providers decline to supply care that is productive for patients, avoiding certain patients and procedures.6

In the last decades, the culture of DM has grown worldwide, especially in high-risk medical areas, because of the ever-increasing number of medical claims.7 In a survey conducted in Pennsylvania, 93% of physicians in 6 specialties at high risk of litigation (emergency medicine, general surgery, orthopedic surgery, neurosurgery, obstetrics/gynecology, and radiology) reported practicing defensive medicine.8 Other surveys show that the 78% of physician in the United Kingdom, the 60% in Israel and the 58.8% in Italy practice DM in hospital.6,9,10

DM would seem to be a phenomenon now structured in the healthcare systems afflicting all the diagnostic-therapeutic settings with severity in some disciplines and wasting a huge amount of human, organizational and economic resources.11

Most of the studies in the scientific literature analyzing the DM phenomenon pay close attention to DM among medical professionals,11 but if defensive practices are a generalized response to malpractice claim, they may occur also in other health professionals.

The aim of this review was to analyze international scientific literature to evaluate:

- -

if DM is carried out/practiced also by Non-Medical Healthcare Professionals (NMHP);

- -

the reasons of practice NMHP-DM;

- -

what kind of defensive practices are performed by NMHP and what are their consequences.

The review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines,12 and specific inclusion criteria were developed to identify relevant papers13–15:

- (1)

phenomena of interest: NMHP-DM;

- (2)

types of participants: this review considered all studies that included NMHP, such as nurses, midwifes, physical therapists, medical laboratory personnel, nutritionists, medical technicians, etc.;

- (3)

types of outcome measures: the aim of this review was to identify if exists a DM performed by NMHP, what are the reasons of NMHP-DM, what defensive practices are performed by NMHP and what are the effects;

- (4)

types of studies: this review considered any qualitative and quantitative research studies that explored DM carried out by NMHP.

Identification of articles was conducted in two stages. Studies were searched in Medline, Embase, Cinhal and Cochrane Library from the start of each database to April 12, 2018. The following keywords and MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms were used in the search: “Defensive Medicine”, “Defensive practices”, “paramedical personnel”, “allied health occupations”, “health care personnel”, “nurses”, “midwives”, “physical therapist”, “medical laboratory personnel”, “nutritionists”, “emergency medical technicians” and “dental auxiliaries”. Boolean Operators were used to link keywords (Attachment A). No language restrictions were applied. In a second research step, a manual review of reference lists from relevant articles identified in the first step was performed. Unpublished articles were not searched. After duplicates removal, articles were screened independently by two reviewers, and if consensus was not reached, a third researcher was involved. Papers evaluated as eligible on the basis of their abstract, were read entirely by the reviewers to establish the compliance with the inclusion criteria. Every step of the research was supervised by two experts in defensive medicine, and the choice of include studies in the qualitative analysis was taken with their agreement. An ad hoc framework was built to collect data.

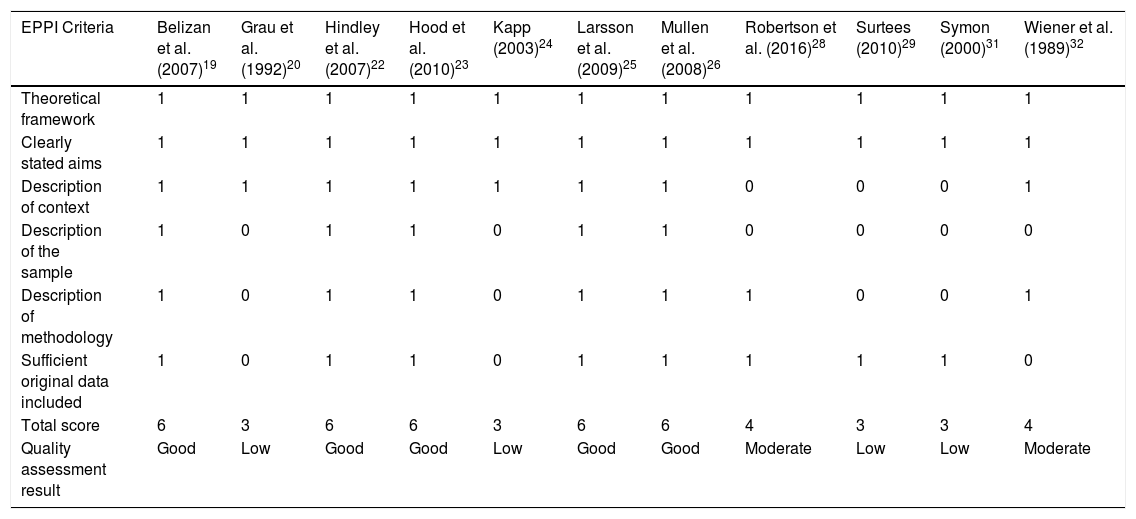

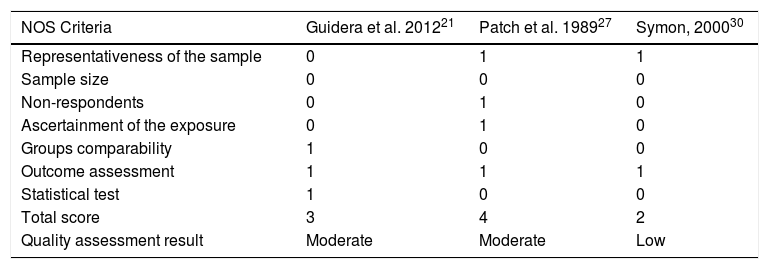

Quality assessmentEvery research paper was assessed for quality and risk of bias (Tables 1 and 2). Quality appraisal of qualitative studies were performed using a standardized framework outlined by the EPPI-Center.16,17 Non-intervention studies were evaluated according to six criteria: (1) an explicit account of theoretical framework and/or inclusion of a literature review that outlines the rationale for the intervention; (2) clearly stated aims and objectives; (3) a clear description of context, which includes details about important factors for interpreting results; (4) a clear description of sample; (5) a clear description of methodology, including systematic data collection methods; (6) inclusion of sufficient original data to mediate between data and interpretation. For each criterion that was met a score of one was given. Studies’ quality was evaluated “good” if all the criteria were met, “moderate” if the score was 4 or 5, “low” if the score was 3. Studies with score 1 or 2 were excluded because of their poor quality. Quality evaluation of cross-sectional studies was carried out using the seven criteria of the adapted Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS)18 and studies’ quality degree was evaluated assigning a score of one for each met criteria. Quality of the studies was judged “good” if at least 5 criteria were met, “moderate” if the total score was 3 or 4, and “low” if the score was 2 or lower.

Quality assessment of qualitative studies – EPPI-Center framework.

| EPPI Criteria | Belizan et al. (2007)19 | Grau et al. (1992)20 | Hindley et al. (2007)22 | Hood et al. (2010)23 | Kapp (2003)24 | Larsson et al. (2009)25 | Mullen et al. (2008)26 | Robertson et al. (2016)28 | Surtees (2010)29 | Symon (2000)31 | Wiener et al. (1989)32 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical framework | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Clearly stated aims | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Description of context | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Description of the sample | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Description of methodology | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Sufficient original data included | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Total score | 6 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Quality assessment result | Good | Low | Good | Good | Low | Good | Good | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate |

Quality assessment of cross-sectional studies – NOS checklist.

| NOS Criteria | Guidera et al. 201221 | Patch et al. 198927 | Symon, 200030 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Representativeness of the sample | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Sample size | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Non-respondents | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Ascertainment of the exposure | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Groups comparability | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Outcome assessment | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Statistical test | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total score | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| Quality assessment result | Moderate | Moderate | Low |

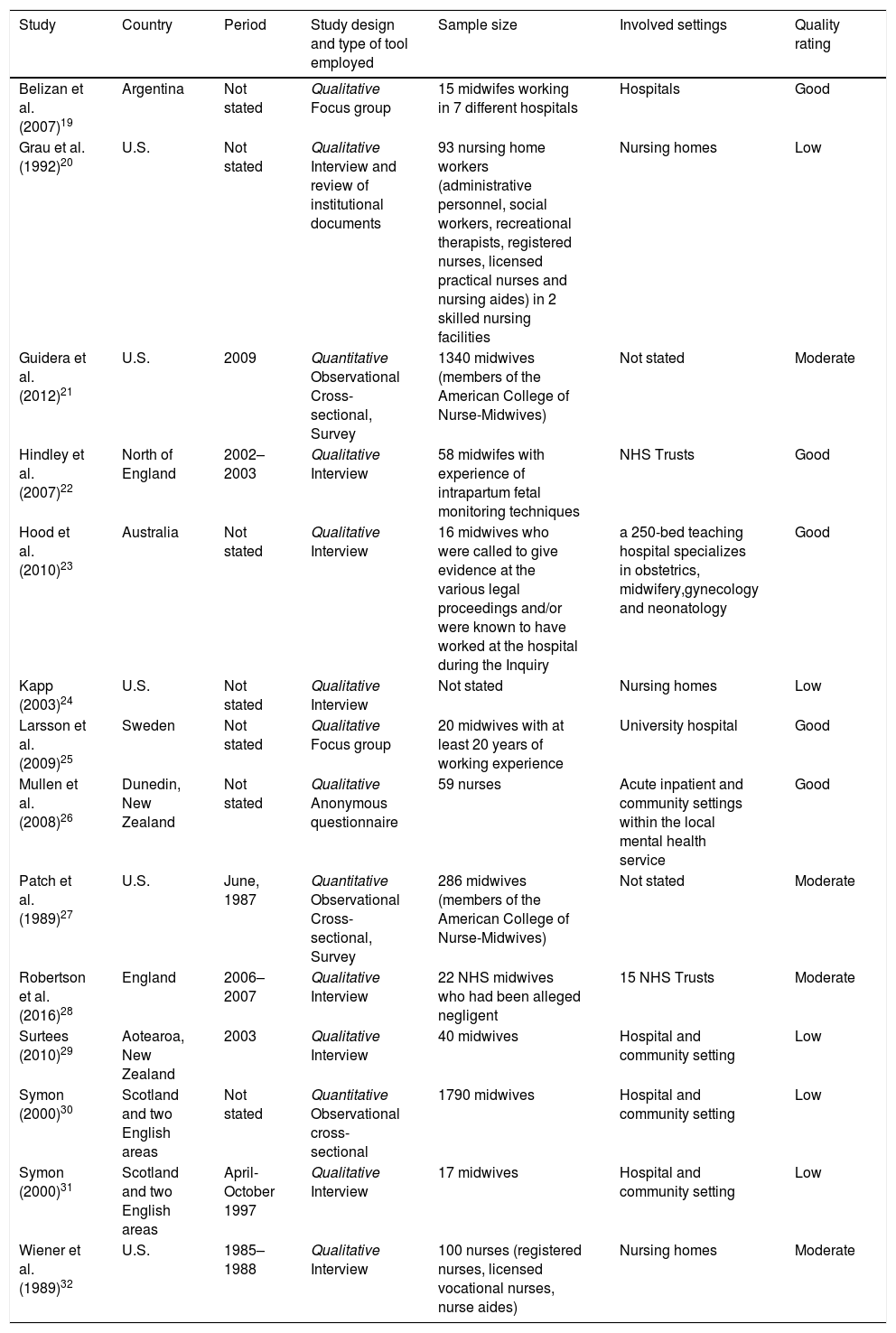

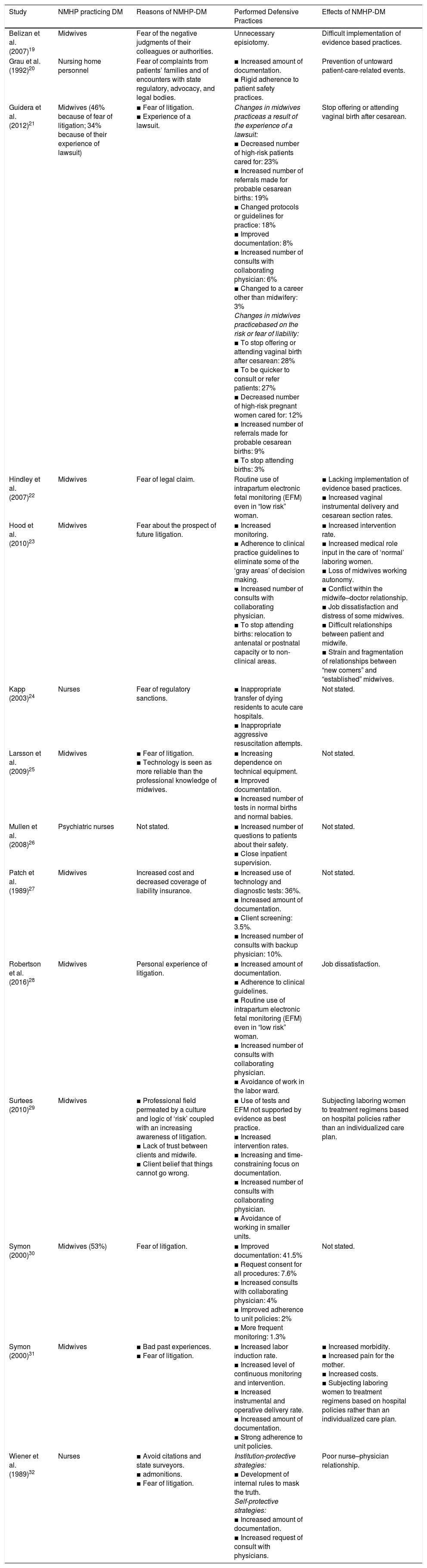

86 potentially relevant studies were identified in the first research, and 5 additional articles were identified through review of papers’ reference lists. After duplicates removal, 72 studies were screened for eligibility through abstracts evaluation, 32 were analyzed reading the full-text and, finally, 14 were considered relevant for the purpose of this paper. An overview of the literature screening process is provided in Fig. 1. Key characteristics and main findings of included studies are displayed in Tables 3 and 4.

Key characteristics of included studies (n=14).

| Study | Country | Period | Study design and type of tool employed | Sample size | Involved settings | Quality rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belizan et al. (2007)19 | Argentina | Not stated | Qualitative Focus group | 15 midwifes working in 7 different hospitals | Hospitals | Good |

| Grau et al. (1992)20 | U.S. | Not stated | Qualitative Interview and review of institutional documents | 93 nursing home workers (administrative personnel, social workers, recreational therapists, registered nurses, licensed practical nurses and nursing aides) in 2 skilled nursing facilities | Nursing homes | Low |

| Guidera et al. (2012)21 | U.S. | 2009 | Quantitative Observational Cross-sectional, Survey | 1340 midwives (members of the American College of Nurse-Midwives) | Not stated | Moderate |

| Hindley et al. (2007)22 | North of England | 2002–2003 | Qualitative Interview | 58 midwifes with experience of intrapartum fetal monitoring techniques | NHS Trusts | Good |

| Hood et al. (2010)23 | Australia | Not stated | Qualitative Interview | 16 midwives who were called to give evidence at the various legal proceedings and/or were known to have worked at the hospital during the Inquiry | a 250-bed teaching hospital specializes in obstetrics, midwifery,gynecology and neonatology | Good |

| Kapp (2003)24 | U.S. | Not stated | Qualitative Interview | Not stated | Nursing homes | Low |

| Larsson et al. (2009)25 | Sweden | Not stated | Qualitative Focus group | 20 midwives with at least 20 years of working experience | University hospital | Good |

| Mullen et al. (2008)26 | Dunedin, New Zealand | Not stated | Qualitative Anonymous questionnaire | 59 nurses | Acute inpatient and community settings within the local mental health service | Good |

| Patch et al. (1989)27 | U.S. | June, 1987 | Quantitative Observational Cross-sectional, Survey | 286 midwives (members of the American College of Nurse-Midwives) | Not stated | Moderate |

| Robertson et al. (2016)28 | England | 2006–2007 | Qualitative Interview | 22 NHS midwives who had been alleged negligent | 15 NHS Trusts | Moderate |

| Surtees (2010)29 | Aotearoa, New Zealand | 2003 | Qualitative Interview | 40 midwives | Hospital and community setting | Low |

| Symon (2000)30 | Scotland and two English areas | Not stated | Quantitative Observational cross-sectional | 1790 midwives | Hospital and community setting | Low |

| Symon (2000)31 | Scotland and two English areas | April-October 1997 | Qualitative Interview | 17 midwives | Hospital and community setting | Low |

| Wiener et al. (1989)32 | U.S. | 1985–1988 | Qualitative Interview | 100 nurses (registered nurses, licensed vocational nurses, nurse aides) | Nursing homes | Moderate |

Main findings of included studies (n=14).

| Study | NMHP practicing DM | Reasons of NMHP-DM | Performed Defensive Practices | Effects of NMHP-DM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belizan et al. (2007)19 | Midwives | Fear of the negative judgments of their colleagues or authorities. | Unnecessary episiotomy. | Difficult implementation of evidence based practices. |

| Grau et al. (1992)20 | Nursing home personnel | Fear of complaints from patients’ families and of encounters with state regulatory, advocacy, and legal bodies. | ▪ Increased amount of documentation. ▪ Rigid adherence to patient safety practices. | Prevention of untoward patient-care-related events. |

| Guidera et al. (2012)21 | Midwives (46% because of fear of litigation; 34% because of their experience of lawsuit) | ▪ Fear of litigation. ▪ Experience of a lawsuit. | Changes in midwives practiceas a result of the experience of a lawsuit: ▪ Decreased number of high-risk patients cared for: 23% ▪ Increased number of referrals made for probable cesarean births: 19% ▪ Changed protocols or guidelines for practice: 18% ▪ Improved documentation: 8% ▪ Increased number of consults with collaborating physician: 6% ▪ Changed to a career other than midwifery: 3% Changes in midwives practicebased on the risk or fear of liability: ▪ To stop offering or attending vaginal birth after cesarean: 28% ▪ To be quicker to consult or refer patients: 27% ▪ Decreased number of high-risk pregnant women cared for: 12% ▪ Increased number of referrals made for probable cesarean births: 9% ▪ To stop attending births: 3% | Stop offering or attending vaginal birth after cesarean. |

| Hindley et al. (2007)22 | Midwives | Fear of legal claim. | Routine use of intrapartum electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) even in “low risk” woman. | ▪ Lacking implementation of evidence based practices. ▪ Increased vaginal instrumental delivery and cesarean section rates. |

| Hood et al. (2010)23 | Midwives | Fear about the prospect of future litigation. | ▪ Increased monitoring. ▪ Adherence to clinical practice guidelines to eliminate some of the ‘gray areas’ of decision making. ▪ Increased number of consults with collaborating physician. ▪ To stop attending births: relocation to antenatal or postnatal capacity or to non-clinical areas. | ▪ Increased intervention rate. ▪ Increased medical role input in the care of ‘normal’ laboring women. ▪ Loss of midwives working autonomy. ▪ Conflict within the midwife–doctor relationship. ▪ Job dissatisfaction and distress of some midwives. ▪ Difficult relationships between patient and midwife. ▪ Strain and fragmentation of relationships between “new comers” and “established” midwives. |

| Kapp (2003)24 | Nurses | Fear of regulatory sanctions. | ▪ Inappropriate transfer of dying residents to acute care hospitals. ▪ Inappropriate aggressive resuscitation attempts. | Not stated. |

| Larsson et al. (2009)25 | Midwives | ▪ Fear of litigation. ▪ Technology is seen as more reliable than the professional knowledge of midwives. | ▪ Increasing dependence on technical equipment. ▪ Improved documentation. ▪ Increased number of tests in normal births and normal babies. | Not stated. |

| Mullen et al. (2008)26 | Psychiatric nurses | Not stated. | ▪ Increased number of questions to patients about their safety. ▪ Close inpatient supervision. | Not stated. |

| Patch et al. (1989)27 | Midwives | Increased cost and decreased coverage of liability insurance. | ▪ Increased use of technology and diagnostic tests: 36%. ▪ Increased amount of documentation. ▪ Client screening: 3.5%. ▪ Increased number of consults with backup physician: 10%. | Not stated. |

| Robertson et al. (2016)28 | Midwives | Personal experience of litigation. | ▪ Increased amount of documentation. ▪ Adherence to clinical guidelines. ▪ Routine use of intrapartum electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) even in “low risk” woman. ▪ Increased number of consults with collaborating physician. ▪ Avoidance of work in the labor ward. | Job dissatisfaction. |

| Surtees (2010)29 | Midwives | ▪ Professional field permeated by a culture and logic of ‘risk’ coupled with an increasing awareness of litigation. ▪ Lack of trust between clients and midwife. ▪ Client belief that things cannot go wrong. | ▪ Use of tests and EFM not supported by evidence as best practice. ▪ Increased intervention rates. ▪ Increasing and time-constraining focus on documentation. ▪ Increased number of consults with collaborating physician. ▪ Avoidance of working in smaller units. | Subjecting laboring women to treatment regimens based on hospital policies rather than an individualized care plan. |

| Symon (2000)30 | Midwives (53%) | Fear of litigation. | ▪ Improved documentation: 41.5% ▪ Request consent for all procedures: 7.6% ▪ Increased consults with collaborating physician: 4% ▪ Improved adherence to unit policies: 2% ▪ More frequent monitoring: 1.3% | Not stated. |

| Symon (2000)31 | Midwives | ▪ Bad past experiences. ▪ Fear of litigation. | ▪ Increased labor induction rate. ▪ Increased level of continuous monitoring and intervention. ▪ Increased instrumental and operative delivery rate. ▪ Increased amount of documentation. ▪ Strong adherence to unit policies. | ▪ Increased morbidity. ▪ Increased pain for the mother. ▪ Increased costs. ▪ Subjecting laboring women to treatment regimens based on hospital policies rather than an individualized care plan. |

| Wiener et al. (1989)32 | Nurses | ▪ Avoid citations and state surveyors. ▪ admonitions. ▪ Fear of litigation. | Institution-protective strategies: ▪ Development of internal rules to mask the truth. Self-protective strategies: ▪ Increased amount of documentation. ▪ Increased request of consult with physicians. | Poor nurse–physician relationship. |

Defensive practices in health care settings are not performed only by physician, but also by non-medical health professionals.19–32 Defensive behaviors are practiced by midwives19,21–23,25,27–31 and by nurses working in nursing homes20,32 and in mental health services.26 Frequency of midwives who admitted to have changed their practice in a protective manner ranges from 34%21 to 53%.30 Data about frequency of defensive practice carried out by nurses are not available.

Weiner and Kaiser-Jones32 outlined two different typologies of defensive practices adopted by NMHP: “institution-protective strategies” (institutional strategic plans carried out to protect the structure against a damage of image or to avoid state surveyors’ admonitions) and “self-protective strategies” (practices performed by NMHP to protect themselves from litigation or from negative judgments). Midwives adopt only self-protective strategies,19,21–23,25–31 whereas nursing homes personnel tend to take both strategies.20,24,32

Question 2: what are the reasons of NMHP-DM?The main reason that induces NMHP to perform defensive practice is the fear of litigation.20–23,25,29–32 Malpractice suit are perceived as common, and health professionals believe to have to protect themselves. In some of them the fear of claim is not only abstractly based on the perception of a potential risk, but has developed following direct lawsuit experiences.21,28,31 The problem of lawsuits is enhanced by the changes occurred in liability insurance, which have increased their costs and decreased their coverage.27 It is easy to understand how fear of litigation can become widespread in this climate of ever more common claims and lower insurance coverage, especially in the obstetric field, one of the most affected by malpractice litigations.8 A further problem is the relationship between patients and professionals. The increasingly clients’ expectations, no longer able to consider the possibility of inauspicious outcomes, added to the resonance given by mass-media to malpractice events, create a climate of distrust which hinders a constructive relationship between patient and health care professionals, and contribute to generate fear of litigation among professionals.20,29 Another type of judgment feared by NMHP is that of colleagues (other NMHP and physicians).19 This shows the persistence of a blame environment where error is seen as a fault to be punished rather than a learning and improvement opportunity. An additional reason of NMHP-DM, observed especially in nursing homes personnel, is the fear of state surveyors’ admonitions.19,20,24,32 In this sense, encounters with state regulatory, advocacy and legal bodies are not perceived as an opportunity of improvement and professional development, but only as an authority tool to find structures’ weaknesses and subject them to sanctions. It is clear that this perception can lead to opportunistic behaviors, such as falsification or omission of clinical notes,32 or even inappropriate treatments such as transfer of dying patients to acute care settings or to aggressive resuscitation attempts.24

Question 3: what defensive practice do NMHP perform and what are the effects?NMHP perform both positive and negative DM. The most common strategy carried out by NMHP is the excessive recording of information in the clinical documentation of patients.20,21,25,27–32 The 41.5% of midwives interviewed in a study stated to have improved documentation because of fear of litigation.30 In another study, the 8% of midwives declared to have implemented documentation as a result of the experience of lawsuit.21 NMHP feel safer recording everything and collecting consent for all procedures (7.6% of interviewed midwives), in order to avoid to be accused of negligence if an adverse outcome occurs.29,30 This is a time-consuming activity, which limits the time spent directly with patients. In some cases, internal roles to mask the truth are developed, leading NMHP to write down untrue clinical notes with the aim of not incurring in state surveyors’ admonishments. In one of the analyzed study, nursing homes’ personnel admitted to write untrue clinical notes in order to protect the institution in case of critical patient's conditions in which usual guidelines could not be applied.32 In other cases, the problem of inapplicability of general guidelines is faced by changing protocols and internal guidelines for clinical practice. This strategy is employed by the 18% of midwives who have had direct experience of lawsuit.21 Other NMHP believe that rigid adherence to guidelines and unit policies could protect themselves from litigation.20,23,28,30,31 In a study, 2% of midwives declared they had adopted this strategy.30 This is a positive factor, which allows to prevent untoward patient-care-related events,20 if it does not result in excessive inflexibility that can lead to treatments based on policies rather than on individualized care plans, losing sight of patient's centrality in the care pathway.29,31 In some cases, DM hinders the implementation of evidence-based practices.19,22 Examples of this problem are the practice of routine unnecessary episiotomy19 and the extensive use of electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) even in low-risk patients, in whom it would be discouraged.22,23,28–31 The increasing dependence on technical equipment and the growing use of diagnostic tests,25,27,29 recorded in the 36% of midwives in a study27 and in the 1.3% in another study,30 is linked to the need to have a supporting documentation if an adverse event occurs, in order to avoid the accusation of negligence.29 But the increasing use of biomedical technology in birth does not reduce maternal and newborn mortality and morbidity.33 The widespread use of EFM causes the identification of sub-normal findings that still determine concern among midwives. This leads to an increasing number of consults with collaborating physician (between the 4% and the 27% of midwives interviewed had made this change in their professional practice) and to a greater number of referrals required for probable cesarean section (9–19% of the interviewed midwives).21,23,28–30 Some consequences are the greater intervention rate in the obstetric field,22,23,29,31 with obvious effects such as increased morbidity and pain for the mother and rise of costs,31,34 and alteration of relationship between midwives and physicians.23 The increased medical role in the care of “normal” laboring women makes midwives feel deprived of their working autonomy, and this leads to job dissatisfaction and distress.23,28 Deterioration of relationship can be observed also between “established” midwives and “new comers”, that are seen not enough cautious and thus a possible danger source for the whole staff, and also between midwives and patients, when pregnant women do not want to conform to professional recommendations.23 Similar problems can be observed in nursing personnel: fear of litigation leads them to increasing impatient supervision, rate of medical consults requested by nurses, inappropriate transfer of dying patients to acute care settings and inappropriate aggressive resuscitation attempts.24,32 These practices cause a large waste of financial resources and the great number of consults required, sometimes without real needs, makes nurses seem incompetent in the eyes of doctors and contributes to a poor nurse–physician relationship.32 Midwives, having greater professional autonomy than other NMHP, practice also negative DM, decreasing number of high-risk patients cared for (12–23% of midwives performing DM) and stopping offering or attending vaginal birth after cesarean (28% of the midwives that had changed their practice based on fear of liability).21,27 An extreme defensive practice of some midwives is the avoidance of working in labor ward and small units, and their relocation to antenatal or postnatal capacity or to non-clinical areas (3% of the interviewed midwives).21,23,28,29

DiscussionThe aim of this overview of the scientific literature was to evaluate if DM is performed by NMHP and to identify features of this phenomenon. Analyzed studies showed that DM is not performed only by doctors but also by NMHP, specifically by midwives and nursing homes personnel. However, it cannot be excluded that this phenomenon also occurs in other NMHP but that no studies have been conducted in these fields. Midwives and nurses working in nursing homes have greater working autonomy compared with other NMHP, and this can lead them to adopt practices more similar to those performed by physicians. Midwives and obstetrics/gynecologists both work in a high risk of litigation setting; 53% of midwives and 45% of obstetricians in Scotland and England declared to have personally changed their practice as a result of fear of litigation.30 In Israel this rate rises at the 97% of interviewed gynecologist.35

Reasons that leads NMHP to adopt defensive strategies are similar to that described for physicians: fear of malpractice litigation,11,20–23,25,29–32 increased clients’ expectation,11,20,29,37 poor trust in insurance coverage and rise of its costs.27,36 Fear of litigation is an obstacle to supply high quality health care also because reduces personnel working efficiency,23 and prevent professionals to learn by errors.38 Colleagues’ (other NMHP and physicians) judgment is feared by NMHP,19 while physician are more worried about reputation loss resulting by a lawsuit.39 Furthermore, nursing home personnel adopt institution protective strategies to avoid state surveyors’ admonitions,19,20,24,32 while neither midwives nor doctors seem to be afflicted by this concern.

NMHP and physician adopt some similar defensive practices. Over-investigation is performed by both midwives and doctors, with increased use of tests, unnecessary diagnostic procedures and greater request of consults and referrals with specialists (10–27% of midwives, 31.5% of gynecologists).8,11,21,23,25,27–30 Both nurses working in nursing homes and doctors are more prone to transfer patients in acute health settings or in emergency department.11,24 Defensive practices carried out by NMHP, but not by doctors, are the excessive and not always truthful recording of clinical information20,21,25,27–32 and the rigid adherence to guidelines and unit policies.20,23,28,30,31 Doctors, instead, tend to prescribe more medications than medically indicated.11 Negative DM is performed by doctors and midwives, but not by other evaluated NMHP, probably because of the major work autonomy of these two professional categories. The 12% of midwives21 and the 25% of obstetrician/gynecologists8 admitted to avoid caring for high-risk patients because of fear of litigation. Furthermore, they both tend to avoid certain procedure or intervention (28% of midwives and 20% of gynecologists8,21).

Sometimes defensive practice performed by NMHP or by doctors can improve quality, enhancing adherence to guidelines8,20; on the other hand, this rigid behavior can hinder the need of customize care plans.29,31 Furthermore, unnecessary invasive procedure and the increased intervention rate create risks of patient harm,8,31 and costs rise.11,40 In addition, job dissatisfaction and poor working relationship can cause health professionals burnout, that, subsequently, can damage also patients and the whole health care system.11,41–48

Study limitationsSome critical issues concerning the internal validity of the present study should be stated. Due to the heterogeneity of the included studies, which collected data through interviews and different ad hoc questionnaires, a comparative synthesis of results was not possible. Heterogeneity in terms of country (United Kingdom,22,28,30,31 Sweden,25 United States,20,21,24,32 Argentina,19 Australia,23 New Zealand26,29) and time period (ranging between 1985 and 2009) in which the studies have been conducted also affects the external validity of the study, because the phenomenon of litigation might vary depending on different way of claims management, coverage of insurance policies and differences in professional tasks. In addition, subjects studied were professionals working in different health settings (hospitals,19,23,25 community settings26,29–31 or both of them26,29–31), and in different health areas (maternal health,19,21–23,25,27–31 mental health,26 and elderly care20,24,32), but not all categories of NMHP were represented (for example, no studies were identified about DM practiced by general hospitals’ nurses). For all these reasons, the present study is not able to describe the true extent of the problem and the correlations between causal factors and effects. It is only possible to draw interesting reflections.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, the present study shows that DM does not concern only physicians but also NMHP, and the reasons leading all health professionals to perform these practices are similar. Work on the error concept and foster a no blame culture are needed to see errors as an opportunity of professional improvement and not as something to mask. Avoid to make professionals feel guilty can prevent them becoming second victims of their errors49–51 and develop “self-protective strategies” like DM. Further studies are needed to better evaluate DM practiced also by NMHP, other than midwives and nurses, and to evaluate main DM causal factors, in order to apply appropriate preventive strategies to contrast defensive professional practice among health care personnel.

Funding sourcesThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.