Healthcare accreditation seeks to promote the organisational change in healthcare organisations from an approach that values the level of progress achieved through a validated reference framework. The aim of this paper is to analyse the role played by accreditation through the experience perceived by health professionals during the process of self-assessment and external evaluation, taking into account three dimensions of analysis: focus on the patient, internal organisation and leadership, and impact on the clinical aspects of healthcare.

Material and methodsDesign: Semi-structured interviews with key informants from clinical management units (CMU) within the Andalusian Health System (Spain). Participants: The key informants in each CMU were the clinical leader, the head of nursing and two health professionals (doctors and nurses). A qualitative research protocol was employed to conduct the semi-structured interviews (n=52 interviews) with physicians and nurses, in order to analyse their experience with the accreditation process.

ResultsThe analysis identified four main outcomes related to the accreditation process perceived by professionals: (1) A benchmarking conceptualisation of the process; (2) Improvements in patient-centred care, quality of clinical records, and organisational culture of the units; (3) Improvement of patient safety culture; (4) As negative outcomes, a slight perception of bureaucratisation and standardisation of the clinical practice.

ConclusionsThe described initiative of accreditation process in Andalusia (Spain) is widely perceived as positive by health professionals since it fosters the organisational change, although it also has a slightly negative bureaucratisation effect on clinical practice.

La acreditación de la asistencia sanitaria trata de fomentar el cambio organizacional en las empresas de asistencia sanitaria desde un enfoque que valora el nivel de progreso logrado a través de un marco de referencia validado. El objetivo de este artículo es analizar el papel desempeñado por la acreditación a partir de la experiencia percibida por los profesionales sanitarios durante el proceso de autoevaluación y evaluación externa, teniendo en cuenta 3 dimensiones de análisis: atención al paciente, organización interna y dirección, y repercusiones en los aspectos clínicos de la asistencia sanitaria.

Material y métodosDiseño: entrevistas semiestructuradas con informantes clave de las unidades de gestión clínica (UGC) dentro del Servicio Andaluz de Salud, España. Participantes: los informantes clave en cada UGC fueron el jefe del equipo clínico, la jefa de enfermería y 2 profesionales sanitarios (médicos y enfermeras). Se empleó un protocolo de investigación cualitativa para realizar entrevistas semiestructuradas (n=52 entrevistas) con médicos y enfermeras, a fin de analizar su experiencia con el proceso de acreditación.

ResultadosEl análisis identificó 4 resultados principales relacionados con el proceso de acreditación percibidos por los profesionales: 1) una conceptualización de referencia del proceso; 2) mejoras en la asistencia centrada en el paciente, la calidad de las historias clínicas y la cultura organizativa de las unidades; 3) mejora de la cultura de seguridad del paciente, y 4) como resultados negativos, una ligera percepción de la burocratización y estandarización de la práctica clínica.

ConclusionesLa iniciativa descrita del proceso de acreditación en Andalucía, España es percibida ampliamente como positiva por los profesionales sanitarios ya que fomenta el cambio organizativo, aunque también tiene un efecto de burocratización ligeramente negativo en la práctica clínica.

The healthcare sector is a leading priority of governments worldwide, because of the expenditure involved, its impact on the population's perception of well-being, countries’ shortcomings and needs, or because it is a fundamental right. Indeed, healthcare and health-related services are a constant concern. Improving quality, from any perspective, is both a challenge and a necessity.1,2 Improving quality requires a change in healthcare organisations and should involve the design of plans and strategies, the development of health professionals and better outcomes.3,4 Only if the improvement has an impact on these three aspects, we can really refer to an improvement in healthcare.

There is an important knowledge base, generated in the last few years, concerning the main areas for improvement within the quality of healthcare services,5,6 and several studies have also been conducted to define the phenomenon of change in healthcare organisations and its different factors.4,7 However, the complexity of healthcare organisations, in regard to dimensions, contexts as well as strategic and policy-making factors, means that the path to improvement will be difficult, slow and costly.8 In order to deal with this reality, different initiatives were fostered that provided greater autonomy in the implementation, monitoring and decision-making regarding care quality, and that were focused on the development of clinical governance and management. Therefore, certification seeks to promote the organisational change in healthcare organisations from an approach that values the level of progress achieved through a validated reference framework.9

Regarding the Andalusian health system (Spain), the purpose of implementing clinical management units (CMU) is to involve health professionals in the management of the resources they use in clinical practice and decision-making processes, in obtaining health outcomes and in user satisfaction. Within this organisational design, health professionals are central in the continuous improvement of healthcare services, because they apply the design, have a greater interaction with users and are the primary data source for evaluating said services. In the last ten years, the clinical services and primary healthcare centres of the main healthcare provider in Andalusia, the Andalusian Health Service (SAS) have been migrating to this organisation model, and almost all the provider's health services are nowadays CMUs.

The Andalusian Agency for Healthcare Quality (ACSA) has an accreditation programme for Clinical Management Units (APCMU) that comprises 109 quality standards. The accreditation process includes a self-assessment period in which CMUs perform an internal review with the APCMU standards as a reference.10 The programme, consisting in evaluating the healthcare services managed and provided by CMUs, aims to foster continuous improvement in these units and, through shared learning, in other components of the system that are closely linked to the CMU (electro medicine, information systems, occupational risk prevention systems, etc.).

If health professionals are central to continuous improvement policies, where accreditation is seen as an improvement resource, what is the perception of accredited CMU's health professionals concerning the role played by accreditation to foster continuous improvement? The purpose of this study is to explore and analyse such perception.

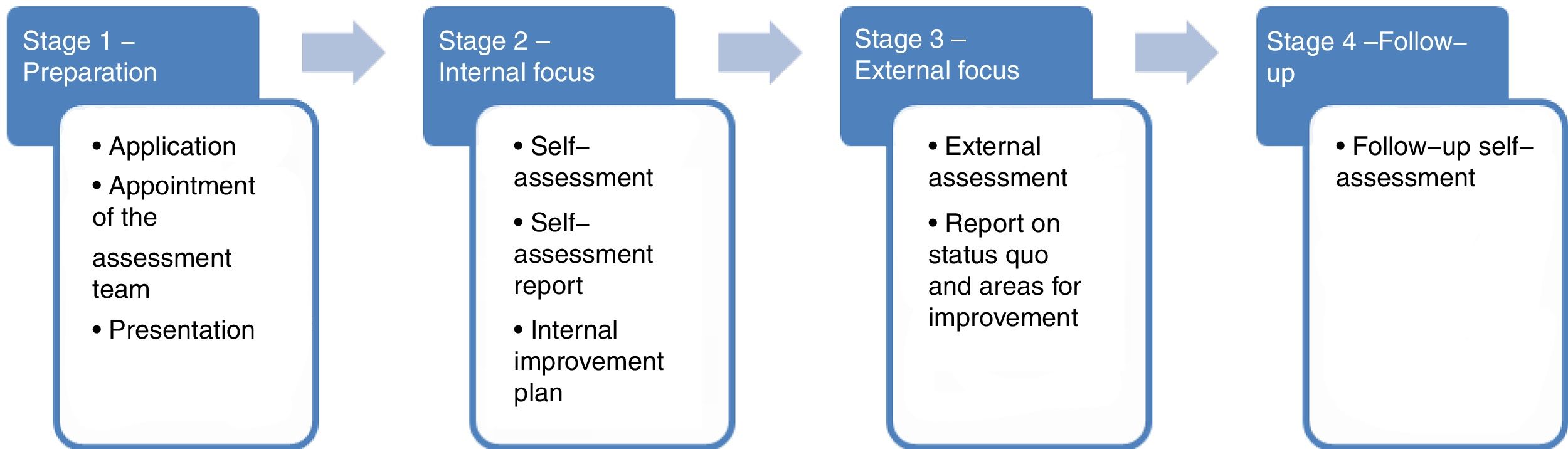

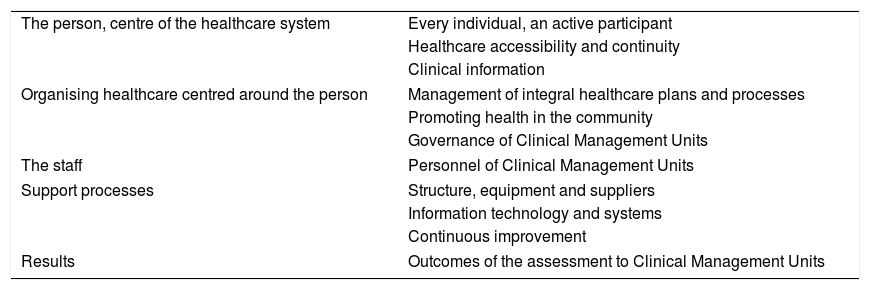

The context of the study was that ACSA's accreditation processes of CMUs are structured in 4 phases (Fig. 1). Having the different APCMU quality standards as a reference, the self-assessment phase enables professionals to analyse their activity and management based on a series of themes and criteria (Table 1). Subsequently, ACSA's evaluation teams carry out assessment visits to verify the information provided in the self-assessment and evaluate its compliance with quality standards. Once the CMU certification is obtained, the follow-up phase begins. During this phase, ACSA makes external assessment visits to check that the compliance with standards is guaranteed and that the identified improvements are still in place. The accreditation is valid for five years.

Structure of the accreditation programme for Clinical Management Units (APCMU).

| The person, centre of the healthcare system | Every individual, an active participant |

| Healthcare accessibility and continuity | |

| Clinical information | |

| Organising healthcare centred around the person | Management of integral healthcare plans and processes |

| Promoting health in the community | |

| Governance of Clinical Management Units | |

| The staff | Personnel of Clinical Management Units |

| Support processes | Structure, equipment and suppliers |

| Information technology and systems | |

| Continuous improvement | |

| Results | Outcomes of the assessment to Clinical Management Units |

In order to conduct the present study, the CMUs in which ACSA carried out the follow-up visits in 2011 and 2012 (n=54 CMU) were selected. The key informants in each CMU were the manager, the head of nursing and two health professionals (doctors and nurses) chosen by the Unit Director. The aim of including directors and the head of nursing as fixed categories in the study's CMUs was not to analyse their answers separately, but to ensure a minimum number of interviews in each CMU. In addition, all health professionals signed an informed consent form regarding the information that they provided. On the other hand, semi-structured interviews were performed until reaching the saturation of information, this is until no new information was generated in the research categories (total: 10 CMUs). In all, there were 52 semi-structured interviews based on the three aforementioned dimensions, corresponding to the previously identified three main factors of change: focus on the patient, internal organisation and leadership, and impact on clinical aspects of healthcare. The interviews and their subsequent analysis were based on the Modified Grounded Theory in order to analyse the proposed objectives while generating new codes and categories of analysis. After the interviews, they were transcribed and the texts were then analysed. Finally, different categories of codes were established, ranging from substantive codes that arise from the study data to more analytical codes with a greater conceptual dimension.

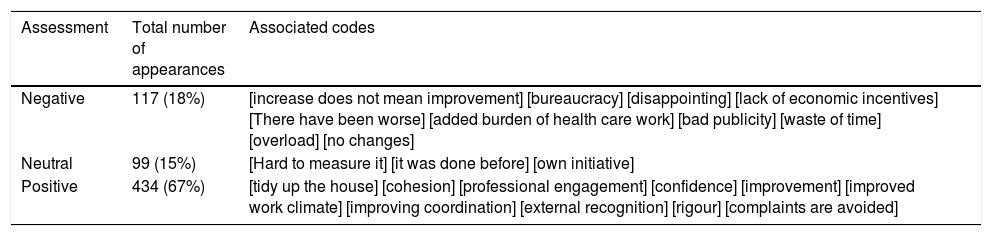

ResultsThe evaluation codes obtained in the interviews with CMU professionals, and the type of evaluation (positive, negative or neutral), are included in Table 2.

Codes extracted from the responses of the interviews.

| Assessment | Total number of appearances | Associated codes |

|---|---|---|

| Negative | 117 (18%) | [increase does not mean improvement] [bureaucracy] [disappointing] [lack of economic incentives] [There have been worse] [added burden of health care work] [bad publicity] [waste of time] [overload] [no changes] |

| Neutral | 99 (15%) | [Hard to measure it] [it was done before] [own initiative] |

| Positive | 434 (67%) | [tidy up the house] [cohesion] [professional engagement] [confidence] [improvement] [improved work climate] [improving coordination] [external recognition] [rigour] [complaints are avoided] |

Results are organised in five different thematic fields according to the main results for each dimension of the semi-structured interviews (see Appendices 1 and 2).

Patient-oriented careThe results obtained in this section are focused on the following fundamental concepts.

Information and communication with patientsThere was a broad consensus among the interviewed professionals, who believed that patients are receiving more information during doctor's visits, as well as more information in writing after the accreditation process. “In a way, [patients] are more aware of their rights and obligations, and more familiar with clinical activity, in which they are important subjects.” (Digestive Diseases Physician, 62.)

They also perceived that accreditation is making user participation more dynamic: “There is greater awareness of the need [for greater user participation] and some groups have included users’ associations to participate in the decision-making process for the edition of protocols.” (Gynaecologist, 51.)

Most of the interviewed professionals believed that accreditation has fostered satisfaction monitoring measures. In many cases, it has led to CMUs establishing their own surveys. However, there is also a less frequent perception that this was already in place before or that it is still pending in CMUs. As for ‘perception of satisfaction’, there were more differences among professionals’ subjective idea of how patients have changed their minds after accreditation.

Team work, internal organisation and leadershipCMU professionals have perceived that decision-making has become democratic after accreditation, with more meetings and a greater involvement of all professionals in establishing targets. Work groups have also been established to coordinate CMUs’ cross-sectional protocols (safety, humanisation, care processes, satisfaction monitoring, etc.) with a series of persons in charge who inform the rest, with an impact on co-responsibility and even on the working environment. “As we are more organised and everything is under control, with unified criteria, etc., this has an impact on patient care, and, as professionals, we feel more satisfied, or at least that is my perception.” (Primary care nurse, 56)

Improvement in professional development, seen as an opportunity to improve the working, economic, training and research conditions, generates contradictory opinions, although accreditation has not led to an improvement in occupational opportunities. There is also a relatively widespread perception of better training opportunities, more tailored to individual needs, and more commitment.

Management by process and optimisation of resourcesProfessionals did not find that accreditation has led to major changes. This possible improvement is an opinion more widespread among doctors and directors than the perceptions of other professionals. The optimisation of work and available resources is another important perceived aspect of accreditation: “[…] we have become much more efficient in our use of resources. We are much more aware. Efficiency in materials, in personnel expenditure, is very important. In the end, what we pursue is quality and less spending.” (Primary Care Unit Director, 51.)

There are three concepts that repeatedly arised during the interviews: patient safety, reduction of variability and care outcomes.

Improvements in patient safetyThere is full consensus on a positive evaluation of accreditation regarding its patient safety improvement. Thanks to it, professionals are also more committed and sensitive to improving organisational dynamics, and clinical record entries. In this regard, changes are clearer, identifying concrete actions which, after accreditation, have reduced and in some cases eliminated risks. The prescription of drugs is seen as a safer process, since standards demand effective patient identification. “The issue of expiry dates, before accreditation, was no one's responsibility. Now the culture is to continually review that the drugs in the hospital are not expired, that dangerous drugs are in suitable places, etc. […] (Endocrinology Director, 47).

Professionals have associated the reduction of variability with the continuous updates required by evidence-based medicine. In this respect, accreditation has been perceived as a catalyst, albeit acknowledging the difficulty of perceiving its impact: “Indeed, we are trying to protocolise actions, methodology, treatments, etc. But it is difficult to measure. My perception is that it's better. There is more discussion, in theory less variability, […] we are trying but it's not easy.” (Paediatrician, 35)

The health professionals consulted in this study were asked about their perception of whether the accreditation of their CMU had improved care outcomes. Some of them had more or less sceptical perspectives regarding the promotion of improvements, while others denied the existence of improvements. Indeed, the greater impact is on internal culture, on the way outcomes are measured and on a greater efficiency meeting the CMU's objectives. “By basing our objectives on reducing waiting lists and increasing patient care, there has been an increase in activity that is reflected in many aspects. Up to 20% increase in activity relative to previous years. This would probably have been different without accreditation.” (Nurse, Digestive Diseases, 46) “Changes no. To be sincere, no. The changes that I have noticed have been a change in people's attitudes, how they see things, etc. But to go from there to a change in results is not easy. First of all, I have not perceived any and, if there are any, they would be very difficult to measure.” (Gynaecologist, 51)

The accreditation phenomenon and the analysis of its impact on healthcare quality is difficult, so the approaches for their study should not have one single dimension if the idea is to appropriately describe the phenomenon. It is important to emphasise organisational culture as an essential factor of any change within the health system. Changes that are not accompanied by a change in the organisation's culture would be imposed and therefore not accepted, and could be exposed to the risk of not becoming consolidated as progress.11,12

Different studies have been carried out in order to assess the impact of accreditation as an element of improvement on health organisations at a general level,13–15 as well as at the level of concrete initiatives.16–19 Results are barely conclusive since the association between accreditation and outcomes has been found very weak.9,15 In our study we have tried to focus on organisational culture changes and on how accreditation influences the dynamism of organisation workflows. We understand that this alternative approach, less frequent in this type of impact analysis, provides richer information.20,21

The Accreditation Programme of Clinical Management Units (APCMU) is pioneer in the accreditation of healthcare quality from a perspective that goes from local to general, as it provides a diagnosis of CMUs that also includes their interrelation with the cross-sectional structures of the hospital, other CMUs, and other levels and healthcare resources. This view, from local to general, facilitates the development of collaborative learning mechanisms within the CMU.12 Following this reasoning, this study aims to describe how professionals perceive the impact of their CMU accreditation process on the organisational chain in order to improve the provision of care. It is a view closer to the local reality of each CMU that can be compared with the objectives of the overall healthcare organisation.22

Firstly, accreditation is conceived as a benchmarking process where self-assessment is the basis of the organisation's collective performance based on pre-established standards.23 The so-called “paradox of success” fosters learning and recognises the good actions of the organisation in terms of quality and patient safety.24 In this respect, recognition by external accreditation positively encourages professionals’ clinical practice,25 which, when applied to a whole regional o national healthcare system, could lead to an overall improvement of healthcare quality.15

Secondly, professionals perceived important improvements that affect patient-centred care and the internal organisation of CMUs. These aspects are consistent with the data obtained from other researches,26,27 and not consistent with other ones.16,28 The collection of information regarding patient satisfaction is seen as more systematic, and there is an improvement in the information provided to patients. One aspect that is not so clearly identified in previous research, regarding new knowledge in the field, is related to a greater involvement of patient associations, patients and their relatives in the management of CMUs. The reason of this could be that the PACMU bases good practices on a micromanagement level and on local participation, however it is more difficult to analyse the changes on big centres, such as hospitals. On the other hand, previous studies have repeatedly found an improvement in the organisation's internal stock capital as a result of accreditation.29 The results found are consistent with these findings, since accreditation led to a greater participation of other professional groups in strategic decisions. The identification of expert professionals responsible for different areas of improvement strengthens the formal and informal links that structure CMUs through their greater involvement in the implementation of improvements.30

Thirdly, all professional groups perceived an improvement in patient safety.31 As identified by Greenfield et al.,32 CMUs have a collaborative self-reinforcement model through changes in the organisation of their work: identification of areas to be improved, distributed leadership, collaborative learning, measurement of results, safety objectives, etc., that act and are strengthened with the improvement in stock capital.

Fourthly, professionals have different opinions on the accreditation process itself. On the one hand, the systematic collection of quality and safety indicators is perceived as an improvement.29 On the other hand, the long process involved in compliance with the Accreditation Programme standards is seen as excessive red tape.33 In sum, accreditation is a process that involves hard work for professionals.

However, the study has some limitations. It does not evaluate the impact of the accreditation process on clinical indicators, an aspect that has to be considered in order to confirm a net positive impact of accreditation on quality and safety. This is due to the complexities involved, as there are previous approaches that obtained very poor results when establishing a relationship between accreditation and outcomes. Likewise, it would be interesting to evaluate the cost-benefit of accreditation processes, as it is being done in other models.34 The sampling was based on a specific accreditation programme and on health professionals within a Spanish region, aiming to present an approach from perspectives that are close to the provision of care, obtaining keys that enable generalisations regarding the health system, and to continue to study the accreditation phenomenon, in an exercise of transparency towards the system itself and its users.2

FinancingThe present article has received financing from the project “Assessment of the Impact of Health Centres Accreditation on Care Quality” with file number PI-0245-2010 related to the call for proposals Projects on biomedical research and health sciences of the Ministry of Health of the Regional Government of Andalusia.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interests.