Needle stick injuries are associated with a 0.3–30% risk of transmission of Human Immunodeficiency virus, Hepatitis C virus, and Hepatitis B virus. Despite causing psychological trauma they also involve a huge financial burden. A robust process improvement (RPI) toolkit was introduced in order to effectively manage and reduce needle stick injuries, as well as an attempt to report prevalence, post-exposure management, and associated economic burden.

Materials and methodsProspective Observational Study (2015–2018) has been design in a Corporate Tertiary Care Hospital. The participants included were needle stick injuries exposed staff. RPI toolkit was implemented (2015–2018) focusing on root cause analysis, availability of safety engineered devices, immunization and post-exposure management of needle stick injuries exposed staff. The main outcome measure was needle stick injuries incidence.

ResultsA total of 211 needle stick injuries were reported (mean – 52.72/year, needle stick injury incidence – 13.18/year/100 beds). Yearly trends showed a decrease of 21.3% in injuries from 2015 (61) to 2018 (48). Half (106, 50%) of the total injuries were reported among nurses. Use of hypodermic needles was involved in 116 (55%) injuries, with 114 (54%) occurring due to nonadherence to hospital policies. Overall, 204 staff had protective immunity, and 135 (64%) of these had completed their Hepatitis B immunizations. The source was known in 165 (78%) cases, and 113 of these cases had an injury from a source with negative viral markers. A 6-month follow-up was completed in 90 cases. No seroconversion was reported. Overall costs incurred in post-exposure prophylaxis was approximately €30,000 (mean cost €143.50/needle stick injury).

ConclusionNurses are most at risk of needle stick injury in healthcare settings. Implementation of RPI toolkit led to a 21.3% reduction in sharps injury incidences. These injuries incur huge financial burden on the hospital. Appropriate immunization strategies saved about €1360 expenditure on post-exposure prophylaxis.

Las lesiones por pinchazos de agujas están asociadas a un riesgo entre el 0,3-30% de transmisión del virus de inmunodeficiencia humana, virus de hepatitis C y virus de hepatitis B. A pesar de causar un trauma psicológico, también implican una elevada carga financiera. Se introdujo un instrumento de mejora robusta del proceso (MRP) para gestionar y reducir eficazmente las lesiones por pinchazos de agujas, así como intentar reportar la prevalencia, gestión postexposición y carga económica asociada.

Materiales y métodosEstudio observacional prospectivo (2015-2018) diseñado en un hospital corporativo de atención terciaria. Los participantes incluidos pertenecían al personal con lesiones por pinchazos de agujas. Se implementó el instrumento MRP (2015-2018) centrado en el análisis de la causa raíz, la disponibilidad de dispositivos con diseño seguro, la inmunización y la gestión postexposición del personal expuesto a las lesiones por pinchazos de agujas. La principal medida del resultado fue la incidencia de dichas lesiones.

ResultadosSe reportó un total de 211 lesiones por pinchazos de agujas (media: 52,72/año, incidencia de lesiones por pinchazos de agujas: 13,18/año/100 camas). Las tendencias anuales reflejaron un descenso del 21,3% en las lesiones de 2015 (61) a 2018 (48). La mitad de las lesiones totales (106, 50%) fueron reportadas entre las enfermeras. El uso de agujas hipodérmicas se vio involucrado en 116 (55%) lesiones, de las que 114 (54%) se produjeron a causa de la no adherencia a las políticas hospitalarias. En general, 204 personas tenían inmunidad protectora, y 135 (64%) de ellas habían completado la estrategia de inmunización frente a la hepatitis B. Se desconoció la fuente en 165 (78%) casos, de los cuales 113 tenían una lesión debida a una fuente con marcadores virales negativos. Se completó un seguimiento a 6 meses en 90 casos. No se reportó seroconversión. Los costes generales relacionados con la profilaxis postexposición fueron de aproximadamente de 30.000€ (coste medio 143,50€/lesión por pinchazo de aguja).

ConclusiónLas enfermeras se encuentran en situación de mayor riesgo de pinchazos por agujas en el ambiente sanitario. La implementación de un instrumento MRP conllevó una reducción del 21,3% en cuanto a la incidencia de lesiones por cortes. Dichas lesiones suponen una elevada carga financiera al hospital. Las estrategias de inmunización adecuadas supusieron un ahorro de cerca de 1.360€ del gasto relacionado con la profilaxis postexposición.

Occupational injuries leading to exposure to blood borne pathogens is a constant threat in healthcare delivery practices. Healthcare workers (HCW) handling sharp devices (scalpels, sutures, hypodermic needles, phlebotomy devices etc.) contaminated with blood or body fluids are at high risk of such exposures. The risk of transmission of blood borne viruses ranges from 0.3% for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), 2% for Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) and 6–30% for Hepatitis B Virus (HBV).1 These exposures may either be a percutaneous injury with sharp objects or contact of nonintact skin/mucous membrane with potentially infectious materials. As per CDC, a needle stick injury (NSI) is defined as the penetration of the skin by a needle or other sharp object, which has been in contact with blood, tissue or other body fluids before the exposure.2

In the healthcare industry, there is an estimated 5.6 million workers who are at risk of occupational injuries in US (OSHA) contributing to 385,000 sharp injuries annually. Out of this 66–88% injuries are preventable with using safety devices.3 In India, it is estimated that out of 3–6 billion injections administered, 2/3rd injections are unsafe.4 In developed countries the prevalence, risk factors and prevention strategies associated with NSI have been studied in great details. However, in developing countries, though the frequency of NSI is found to be high, 40–75% of them go unreported leading to underestimation of the rates.5

The risk of NSI is increased with inadequate training, overwork conditions, high-stress interventions (diagnostic or therapeutic endoscopy, biopsy, wound closure etc.), and nonadherence to policy such as recapping of needle, nonusage of safety devices, improper handling and segregation of sharps.6 Each NSI incurs a number of direct and indirect costs.7 This includes time and cost spent in post exposure prophylaxis (includes cost of investigations and treatment for exposed and source if known), cost of replacing an infected staff if required, counselling exposed staff and legal implication if any.8 The economical burden varies from €4 million to €7 million in developed countries.9 The few studies in which cost analysis of NSIs was performed in India reported the average cost per NSI as 2086.5 rupees.8 Safer sharp practices need to be adopted to decrease NSI incidences. In 2008, Joint Commission (JCI) embarked a quality initiative called Robust Process Improvement (RPI) in order to improve care, treatment and services in healthcare industry. RPI tool kit involves lean, Six Sigma and change management.10 Implementation of RPI tools in reduction of needlestick injuries is a novel approach. We have adopted this strategy in our hospital to effectively manage and reduce the NSI incidences over a period of four years. Moreover, we analyzed the prevalence, factors responsible, post exposure prophylaxis and economic burden associated with each NSI case reported.

Material and methodsThe present study is a prospective analysis of NSI incidences that occurred in a 400 bedded corporate tertiary care hospital in North India over a period of four years (January 2015 to December 2018).

Inclusion criteriaAny injury/cut by a sharp object which has been in contact with blood, tissue or other body fluids before the exposure reported within 72h time has been included.

Exclusion criteriaInjuries with noncontaminated sharps or those reported after 72h were excluded.

Post exposure prophylaxisEach needle stick injury which was reported from the area was subjected to the recommended prophylaxis as per the hospital policy. The exposed staff filled an incident form with the help of area in-charge and reported to Emergency (ER) department for immediate treatment. The ER doctor upon understanding the situation and cause of NSI generated an appropriate prescription. The information about type of device, source status, site and depth of injury, procedure associated and vaccination status of exposed was obtained for prescribing the appropriate regimen. Following this, the exposed person was taken for consultation by an internal medicine doctor to decide post exposure prophylaxis based on the source status (known/unknown) (Flowchart 1). Each NSI case was followed up for 6 months with intermittent investigations.

Data collectionAll the duly filled needle stick injury forms during the study period were examined for their completeness and stored in infection control department. They served as source of information for data collection and analysis. All the available data was entered in computers for further statistical analysis.

Implementation of Robust Process Improvement (RPI)At Artemis we have been tracking and reporting NSI data on monthly basis as a quality indicator since October 2008. Yet the root cause analysis was not so effective as to design the improvement strategies. In 2015, we adopted the RPI toolkit and implemented it using a multifaceted approach following this steps:

- 1.

Analysis of Baseline data: NSI prevalence in previous years from 2009 to 2014

- 2.

Prospective implementation of RPI toolkit since January 2015

- •

Root Cause Analysis (RCA) for each NSI: NSI incident reporting form was modified to include factors associated with injury and to record information for identifying appropriate RCA.

- •

Identify factors critical to quality improvement: This included availability and use of safety devices, appropriate disposal of sharps, staff training on prevention of NSI.

- •

Availability of safety engineered devices: Eclipse needles and safety cannula.

- •

Appropriate disposal of Sharps at source: Availability of Puncture proof, sealable sharp containers at points of sharp generation.

- •

Emphasis on training: our approach was to partner with staff and leaders to seek, commit and accept change. Training sessions included internal and external trainings, classroom and demonstrations and audio- visual sessions etc.

- •

Hepatitis B Vaccination drive: to achieve 100% vaccination in critical areas is one of the measurable goals for year 2015. Vaccination reminders initiated as mailers and messages to mobile phones on vaccination days (twice a month). Special vaccination drive for critical care areas was conducted for the staff that could not come for regular vaccination days due to busy schedule.

- •

Modified Post exposure prophylaxis: prevention of HIV, Hepatitis B virus and Hepatitis C virus transmission.

- •

Effective tracking of follow up of Needle stick injuries: Each NSI case was followed up till 6 months. The prophylaxis was given on day of incident and later the follow up was done at 3 regular intervals of 6 weeks, 12 weeks and 6 months from the day of incident. This was done keeping in mind the window period of infections.

The data was statistically analyzed using SPSS 21.0 software and the descriptive statistics were applied for computing NSI incidence and its relationship with associated factors.

ResultsPrevalence of needle stick injuriesBaseline Analysis: There was a gradual increase in the trend in needle stick injuries reported between 2009 and 2014. A total of 222 needle stick injuries occurred over a period of 6 years (Mean – 37 per year). Maximum injuries 47 were reported in year 2014. There may be underreporting of injuries during this period due to lack of adherence to NSI reporting protocols by the staff and inadequate awareness.

Prospective study with interventionA total of 211 needlestick injuries were reported over a period of four years from 2015 to 2018 (Mean – 52.75 per year). The NSI incidence reported per year/100 beds was 13.18. Likewise, the risk of NSI for each working day in the hospital is 0.036. Yearly trends of NSI reported a decreasing trend from 61 in 2015 to 48 in 2018 (21.3% reduction) (Fig. 1).

Among the healthcare workers, the highest number of NSI was reported from nurses (106, 50%). This is followed by Housekeeping staff (35, 17%), Doctors (33, 16%), Ground Duty Assistants (GDA 21, 10%), Technicians (11, 5%) and others (5, 2%) (Table 1). Prevalence of NSI in various clinical areas reported was maximum from wards (71, 34%) followed by the high risk areas like ICUs (59, 28%) and operation theatre (37, 18%). Outpatient department (OPD) reported relatively less injuries (28, 13%).

Distribution of needle stick injuries (2015–2018).

| Variable (n=211) | N | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Staff category | ||

| Staff nurse | 106 | 50.24 |

| Doctors | 33 | 15.64 |

| Housekeeping | 35 | 16.59 |

| GDA | 21 | 9.95 |

| Technicians | 11 | 5.21 |

| Other (GRO, floor coordinator, trainee) | 5 | 2.37 |

| Areas | ||

| ICUs | 59 | 27.96 |

| Wards | 71 | 33.65 |

| Emergency | 2 | 0.95 |

| OPD | 28 | 13.27 |

| Operation theatre | 37 | 17.54 |

| Organ transplant unit | 4 | 1.90 |

| Day care | 10 | 4.74 |

| Devices associated | ||

| Hypodermic needle | 116 | 54.98 |

| Lancet | 22 | 10.43 |

| Suture needle | 17 | 8.06 |

| Eclipse needle | 5 | 2.37 |

| IV cannula | 14 | 6.64 |

| Insulin pen | 12 | 5.69 |

| Surgical blade | 13 | 6.16 |

| Epidural needle | 4 | 1.90 |

| Renal biopsy | 3 | 1.42 |

| Stapler pin | 3 | 1.42 |

| Fistula needle | 1 | 0.47 |

| Implant rod | 1 | 0.47 |

| Root cause analysis | ||

| Procedural accident | 90 | 42.65 |

| Nonadherence to policy | 114 | 54.03 |

| Lack of training | 7 | 3.32 |

| Vaccination status on the day of incident | ||

| Complete | 135 | 63.98 |

| 1st dose | 21 | 9.95 |

| 2nd dose | 48 | 22.75 |

| Nonimmunized | 5 | 2.37 |

| Nonresponder | 2 | 0.95 |

| Follow ups | ||

| On the day of incident | 33 | 15.64 |

| 1st follow up | 23 | 10.90 |

| 2nd follow up | 65 | 30.81 |

| Complete | 90 | 42.65 |

116 (55%) injuries involved the use of hypodermic needles. Lancet and Suture needles caused 10% and 8% NSI respectively. Other devices contributing lesser proportion (27%) were IV cannula, surgical blade, insulin pen, eclipse needle, epidural needle etc. Root cause analysis of the injuries reported that 114 (54%) have occurred due to nonadherence to hospital policies. The rest of it included procedural accidents (90, 43%) and inadequate training (7, 3%).

Vaccination status and Follow up of Exposed healthcare workersImmunization status was an important parameter measured for all those exposed to NSI. A Hepatitis surface antibody titre of >10mIU/ml is considered as protective. In our study, 204 staff had protective immunity whereas 7 had a titre <10mIU/ml. Out of these 7 staff, 1 had NSI from Hepatitis B positive source and was administered immunoglobulins, 2 were nonresponders and were transferred to nonclinical areas. For the Remaining 4 cases, all were revaccinated for complete course of Hepatitis B vaccination. Out of 204 staff with protective titre, 135 (64%) completed all 3 doses, 48 (23%) staff completed 2 doses and 21 (10%) completed only 1st dose of Hepatitis B vaccination.

Out of 211, 90 (43%) have completed all three follow ups for 6 weeks, 12 weeks and 6 months. However, 65 (31%) reverted for two follow ups (upto 12 weeks) and 23 (11%) completed only 1st follow up (6 weeks). In contrast, 33 staff (16%) have not turned for follow up at all. We have a policy to send reminders on e-mails and mobiles twice a month to those who are due for follow up. These 33 staff were either absent/left the organization during the follow up period. Hence, they could not be screened. None of the cases screened for follow up have reported seroconversion.

Evaluation of sourceAs per the source status evaluation, in 165 (78%) injuries out of 211 the source could be identified. The viral marker tests for HIV, HBV, HCV were negative in 113 (68.5%) cases. Among the rest of 52 cases, 12 were HIV positive, 25 HBV positive and 15 HCV positive respectively. Out of 25 NSI with HBV positive source, one exposed had a titre <10mIU/ml and had an administration of Hepatitis B Immune globulins. 12 staff exposed to HIV positive source and 46 cases where source was unknown (21.8%) were given retroviral therapy for 4 weeks.

Economic burden of Needle stick injuriesEach NSI incurs some cost in terms of post exposure prophylaxis (PEP). It includes basic lab investigations and treatment cost. PEP varied according to the source status. The initial cost of PEP for each NSI varied from US$ 59.23 to US$ 132.12 depending upon the type of prophylaxis given (Table 2). This cost increases with each follow up till 6 months. As per the follow up data, there was no seroconversion reported in the NSI exposed staff.

Economic burden of needle stick injuries (NSI).

| Cost incurred per NSI (in US$) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Source Known | Source unknown | |||

| Viral marker negative | HIV positivea | Hep B positiveb | Hep C positivec | ||

| On the day of incident | 59.22 | 98.12 | 59.22 | 59.22 | 98.12 |

| 1st follow up | 106.34 | 145.25 | 106.34 | 169.98 | 145.25 |

| 2nd follow up | 153.47 | 192.37 | 153.47 | 153.47 | 192.37 |

| Complete | 200.6 | 239.5 | 200.6 | 264.23 | 239.5 |

| No of cases prophylaxis administered | 113 | 12 | 25 (1 nonimmunized) | 15 | 46 |

Worldwide needlestick injuries pose a significant threat to healthcare workers which is associated with tremendous emotional and financial stress apart from causing risk of deadly infections.6 The present study reported important data on prevalence and factors associated with NSI in a corporate tertiary care hospital. Introduction of financial implications of each NSI is a critical finding of our study. We have reported a total of 211 NSI during the four year study period showing an incidence of 13.18 injuries per year per 100 beds. Similar figures have been reported by previous studies as 14 per person per year.11 Among the healthcare workers, nurses reported the maximum injuries (50.24%). A Chinese study12 reported it to be 44.3% and from Poland 39.3%.13 Various reports from India [Delhi14 and Mumbai15] as well as from abroad [Saudi Arabia16] have reported similar trends in nurses (19.2–28.5% injuries). On the contrary, a similar study has reported maximum injuries in doctors as 73.7%.5 Nurses are at increased risk of NSI as they have higher exposure to sharp devices; exhibit nonadherence to policy and bear extra work pressure due to high attrition rates. Nonavailability of resources such as safety engineered devices is also a concern in low-income countries.

Immunization against Hepatitis B virus plays an important role in deciding the PEP for an exposed. 69 out 211 (32.7%) had incomplete vaccination status (took either first dose or 2 doses only) yet they showed protective immunity (titre >10mIU/ml). We reported 7 (3.3%) cases out of 211 having a Hepatitis B titre <10mIU/ml (Table 3). One of them had NSI with Hepatitis B positive source and thereby had immunoglobulins administered. Among the rest 6 cases, 2 were nonresponders and transferred to nonclinical areas possessing low risk. Remaining 4 were re-vaccinated and developed protective titre later on. All 6 of them had injury with known HBV negative source and hence were considered safe. All exposed cases who have not completed their vaccination were encouraged to complete the same as part of PEP.

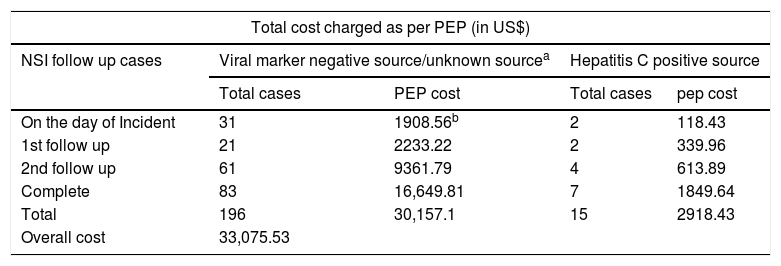

The financial implications of needle stick injuries are high. Each NSI imposes huge economic burden on the hospital in terms of post exposure prophylaxis (PEP). This involves cost of viral marker tests (HIV, HCV and HBV), liver function test and molecular tests for HCV and retroviral drugs (Table 2). This consists of PEP provided on the day of incidence and all follow ups. In our study, the overall cost incurred by the hospital in PEP for 211 NSI cases was approx. US$ 33,075.53 and the average cost being US$ 156.79 (Table 4). A similar study from South India reported total cost as 4.23 lakhs rupees and average cost per NSI as 2086.5 rupees.8 A study conducted by the Healthcare Quality Promotion division of CDC in 4 healthcare facilities in United States reported that the overall cost to manage the reported exposures ranges from $71 to $4838.17

Overall cost charged as post exposure prophylaxis.

| Total cost charged as per PEP (in US$) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSI follow up cases | Viral marker negative source/unknown sourcea | Hepatitis C positive source | ||

| Total cases | PEP cost | Total cases | pep cost | |

| On the day of Incident | 31 | 1908.56b | 2 | 118.43 |

| 1st follow up | 21 | 2233.22 | 2 | 339.96 |

| 2nd follow up | 61 | 9361.79 | 4 | 613.89 |

| Complete | 83 | 16,649.81 | 7 | 1849.64 |

| Total | 196 | 30,157.1 | 15 | 2918.43 |

| Overall cost | 33,075.53 | |||

The PEP varied as per the source status (known/unknown) and the type of infection carried by the source (HIV, HBV and HCV). Our study reported 113 NSI cases where viral marker of the source was negative. Such cases were provided basic PEP which costs US$ 200.65 for each NSI case reported in this category. For a HIV positive source each NSI charged US$ 239.56 to the hospital (12 cases) as an extra amount of US$ 38.91 (cost of retroviral drugs) is added to the basic cost. Likewise, PEP for Hep C positive source involved RNA qualitative PCR test done twice in the entire duration (6th and 12th Week follow up) bringing the overall cost of each NSI prophylaxis to US$ 264.3 and incurring a total cost of US$ 2918.43 for 15 cases reported.

In case of Hepatitis B positive source each NSI charged US$ 200.65 for total 25 cases. Out of this, 24 were immunized against HBV showing a protective titre >10mIU/ml whereas 1 was nonimmunized and had to be administered immune globulins charging a total of approx Rs US$ 273.54 for PEP (additional cost of US$ 72.89 on the base price).

We believe in “Prevention is better than cure”. Under this goal, Hepatitis B vaccination is being provided to all employees free by the hospital. Therefore the 24 cases who were exposed to NSI from Hepatitis B positive patient had 6–30%18 chances of seroconversion if their titre had been low. Moreover, the cost of Immunoglobulins for these cases comes to around US$ 1737.16. In contrast, the amount spent on vaccination of these individuals is US$ 257.16 (collectively for 3 doses of vaccination). Therefore, the cost saved on PEP for immunized individuals is approx. US$ 1480. Cost of post exposure prophylaxis is an additional burden on the organization which can be minimized by providing vaccination (against for Hepatitis B virus) and education to the staff.

NSI cases where source remains unknown are considered as positive and PEP is designed accordingly. The economical burden imposed by each NSI is US$ 239.56 (retroviral drugs cost included). In our study 46 cases were included in this category costing an overall amount of US$ 11,020.54. Malley reported that the cost of PEP for HIV and HBV positive source ranges from US$ 357 to US$ 1626 accounting for 33% of overall cost.17

The increasing cost associated with NSIs is a critical concern which demands designing and implementing quality improvement strategies for prevention of these injuries. Interventions targeted at education and training, better safety devices, decreased patient load per healthcare worker, positive work environment and adhering to standard precautions at all times may prove beneficial.18 In our study, the implementation of robust process improvement toolkit was an effective intervention in this regard. It had a multipronged approach (referred to multiple elements of RPI) which concerted to bring a gradual decrease in NSI from 61 in 2015 to 48 in 2018.

The present study certainly has few limitations. Firstly, all 211 NSI cases have not completed their follow ups till 6 months which would have provided a better understanding about seroconversion. Secondly, though the NSI policy is available for access and continuous training is provided to staff, yet under reporting exists due to which we might have lost some cases. Thirdly, the cost involved in time lost on NSI prophylaxis was not estimated in the present study. These problems can be addressed as an extension to this study or a separate subset in future.

ConclusionNeedle stick injuries are an issue of employee safety which need immediate attention and incur huge costs. They can be prevented by implementing robust process improvement toolkit in the healthcare processes. Components of RPI toolkit included availability of safety engineered devices, sharps disposal at source, Hepatitis B vaccination drive, root cause analysis etc. Cost of post exposure prophylaxis is an additional burden on the organization which can be minimized by providing vaccination (against for Hepatitis B virus) and education to the staff.

FundingNo external source of funding exists.

Conflict of interestNone declared.

We owe our great thanks to Artemis Hospitals for extending their kind support and encouragement in conducting this study.

No potential conflict of interest in terms of financial and other relationships exist and it is applicable to all the three authors (Namita Jaggi, Pushpa Nirwan and Meenakshi Chakraborty).