Patient safety is a global concern, and anaesthesiologists are critically involved in patient safety-related measures and practices. Although anesthesia service has improved a lot over the last few decades, the information on the anesthesia practice and patient safety in India is lacking. The present survey was aimed to get the information on these aspects.

MethodsA cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey including both postgraduate trainees and anaesthesiologists, working across the different hospitals of India was conducted during February–May 2019. Google form was used as the survey; responses were directly downloaded as an Excel file and calculated in absolute numbers and percentages. Autonomous teaching institutes (ATI) were taken as standard, and Fisher's exact test was used for comparisons; P<0.05 was considered significant.

ResultsSix-hundred (86.1%) responses were included for analysis. Pulse oximetry and non-invasive blood pressure (NIBP) were available in nearly 99% set-ups, but end-tidal carbon-di-oxide (EtCO2), temperature, oxygen, and anesthesia gas analyzer were lacking. ATI and corporate teaching hospitals were having almost all standard monitoring, but patient safety-related advanced equipment and medications were not present in many of the hospitals. The lack was highest in both public and private non-teaching hospitals (P<0.0001).

ConclusionPatient safety and anesthesia-related services in India are unsatisfactory. Except for pulse oximetry and NIBP, the public and private sector non-teaching hospitals were lacking even the standard monitoring. Referral and top-level corporate and public sector institutes also have scope for improvement.

La seguridad del paciente es una cuestión de preocupación global, y los anestesiólogos están seriamente involucrados en las medidas y las prácticas relacionadas con la seguridad. Aunque el servicio de anestesia ha mejorado mucho en los últimos decenios, India carece de información acerca de la práctica anestésica y la seguridad del paciente. El objetivo de esta encuesta fue obtener información relativa a estos aspectos.

MétodosEncuesta transversal basada en un cuestionario que incluyó a estudiantes de posgrado y anestesiólogos que trabajaban en diferentes hospitales de India, realizada de febrero a mayo de 2019. Se utilizó un formulario Google® como encuesta, descargándose directamente las respuestas en forma de archivo Excel®, respuestas que se calcularon como cifras absolutas y porcentajes. Se tomaron como estándar las instituciones autónomas docentes (IAD), utilizándose la prueba exacta de Fisher para realizar las comparaciones. Se consideró significativo el valor p<0,05.

ResultadosSe incluyeron para análisis 600 respuestas (86,1%). Se disponía de pulsioximetría y presión arterial no invasiva (PANI) en cerca del 99% de los centros, pero se carecía de dióxido de carbono espiratorio final (EtCO2), temperatura, oxígeno y analizador de gases anestésicos. Las IAD y los hospitales docentes corporativos contaban con casi todos los sistemas estándar de monitorización, pero los equipos avanzados y medicaciones relacionados con la seguridad del paciente no estaban presentes en muchos hospitales. Esta carencia fue mayor en los hospitales públicos y los hospitales privados no docentes (p<0,0001).

ConclusiónLa seguridad del paciente y los servicios relacionados con la anestesia en India son insatisfactorios. Excepto en lo relacionado con la pulsioximetría y la PANI, los hospitales públicos y privados no docentes carecían incluso de monitorización estándar. Los institutos de referencia y los institutos corporativos de alto nivel y del sector público son también susceptibles de mejora.

The Anaesthesiology, as a medical specialty, has contributed significantly toward improving perioperative patient safety and outcome. Today, the specific risk of anesthesia per se is low, but anesthesia contributes to the overall perioperative risk of patients.1 Nearly fifty percent of all adverse events in hospitalized patients are related to surgical care, and one-fourth of the patients who undergoes inpatient operation suffers from complications. Furthermore, at least half of the cases in which surgery led to harm are considered preventable.2 Therefore, patient safety, which is about the reduction and, if possible, elimination of avoidable harm to the patients, is of utmost importance in the perioperative period. Several interventions and safety measures have proven mortality and morbidity benefits during perioperative care. The changes in technology, such as anesthetic delivery systems and monitors, the application of human factors, the establishment of reporting systems are a few of them.3 As the anaesthesiologists are the primary caretaker of the patients undergoing surgery during the perioperative period, their work conditions and practices are likely to reflect the patient safety scenario well. The present survey was aimed to get the information about different safety measures and monitoring available to the anaesthesiologists working across different hospital set-ups of India.

Materials and methodsThe present cross-sectional, national-level survey was conducted after getting approval from the affiliated institute with an exemption for consent and ethical review. Clinical trial registration was not required as per the rule of the Clinical Trial Registry of India. This survey was created and conducted using free online survey software and questionnaire tool service from Google Forms (https://docs.google.com/forms from Google LLC; Mountain View, California, United States) during February 2019 to May 2019. An electronic link to the Google form page containing the survey was sent to anesthesiologists affiliated with the different organizations across India via emails as well as WhatsApp (WhatsApp Inc.; Menlo Park, California, United States) in a few anesthesia-related groups of India. Both qualified practicing anesthesiologists and trainees (i.e., residents) were eligible to be included. If no response was received from the potential respondents within two weeks of the request, a reminder email or message was sent until the end of the survey. Responses were collected anonymously via the survey.

A questionnaire with predetermined multiple-choice options was developed internally by one author, was reviewed and edited by another author, and finally was validated by the other author along with one external anesthesiologist. The online survey questionnaire consisted of 18 questions (Annexure A) covering three specific aspects, i.e., workplace and experience, preparation for the case and patient monitoring, and patient safety-related drugs, equipment, and critical incidents reporting. The survey questions were designed to obtain necessary information about the practitioner's hospital type and sector {i.e. Autonomous Teaching Institutes (ATI), government medical colleges (GMC), private medical colleges (PMC), corporate teaching hospitals (CTH), government non-teaching hospitals (GNTH), and private non-teaching hospitals (PNTH)}, and experience of the responder. Preparation for the case and patient-related monitoring questionnaire had questions aimed at obtaining data related to preoperative machine checking, drug preparation, essential monitoring, and advanced monitoring. The American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) standard monitoring, the Association of Anaesthesiologists of Great Britain and Ireland (AAGBI) patient safety, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia (ASRA), the World Health Organization-World Federation of Societies of Anaesthesiologists (WHO-WFSA) international guideline for patient safety, the All India Difficult Airway Association (AIDAA) guideline were taken as the basis for preparing the questionnaire. The survey questionnaire was in English only version.

The sample size for the present survey was calculated using the online free epidemiological tool, ‘OpenEpi’ (www.openepi.com). A hypothesized frequency (proportion) of the outcome, i.e., patient safety measures of 70%, with an absolute precision of 5% for a large population was taken. A design effect of 1.8 was also applied for the non-randomized nature of sampling. This gave us a sample size of 581 for 95% confidence level and 80% power. Therefore, we decided to conduct the survey either for the predetermined four months or till the desired numbers of responses were obtained, whichever is more.

The responses were directly downloaded from the Google form as an Excel file master chart. Post-download, grossly incomplete responses were excluded, and apparent discrepancy in the responses was processed for possible correction. If the discrepancy was not apparent, it was left as it is. The data were then expressed in absolute number and percentage scale. The processed master data was also divided into different groups based on the workplace and were further compared using Fisher's exact test and INSTAT software (GraphPad Prism Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, Unites States) for finding the differences. The ATI was taken as the standard, i.e., control for the purpose and a two-tailed P-value less than or equal to 0.05 was considered as significant.

ResultsApproximately 3000 anaesthesiologists were approached for the survey, and a total of 615 (20.5%) responses were obtained. Fifteen responses (2.4%) were excluded from the analysis because of incomplete data, and a total of 600 (97.6%) responses were included. Five (0.8%) responses required slight data processing (from non-teaching to teaching where the responses showed to have residents but also indicated as a non-teaching hospital) for only one option/question.

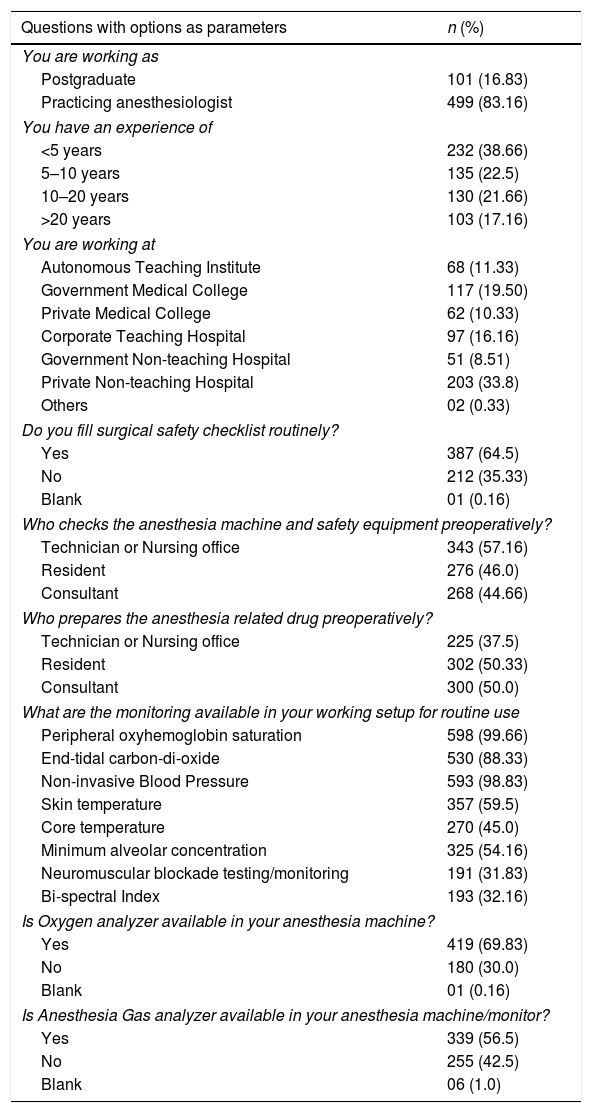

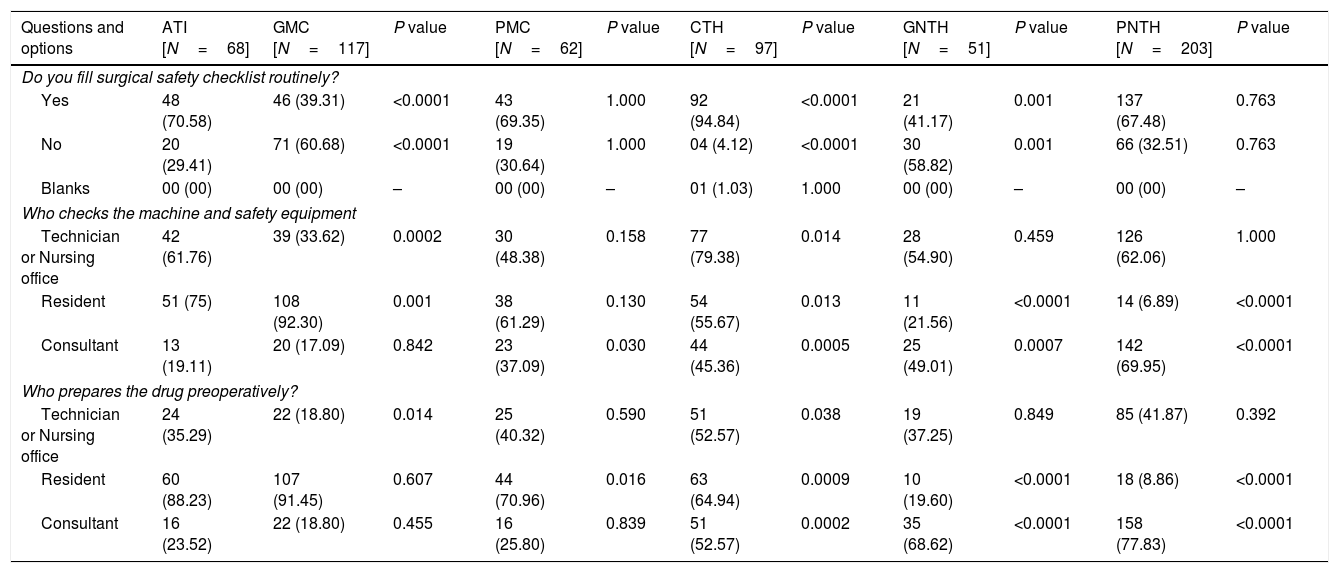

The majority of the responders were young generation anaesthesiologists with less than ten years of experience and those working in teaching hospitals. Nearly 99% of responders were using peripheral oxyhemoglobin saturation (SpO2) and non-invasive blood pressure (NIBP) routinely followed by end-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2) by 88%. Preoperative surgical safety checklist use was, however, only 64.5%. Similarly, an oxygen analyzer was available to only 69.8% responders (Table 1). The compliance with the preoperative surgical safety checklist was significantly higher in the CTH (94.8%; P<0.001); it was similar in PMC and PNTH, and significantly lower in GMC and GNTH, as compared to the ATI (i.e., 70.6%) (Table 2). Pre-anesthetic anesthesia machine check-up and drug preparations were mostly done by residents in the teaching hospitals, and consultants and technicians equally in non-teaching hospitals.

Number and percentage distribution of responders, availability and practice of standard and essential monitoring and pre-anesthetic preparations in the cohort.

| Questions with options as parameters | n (%) |

|---|---|

| You are working as | |

| Postgraduate | 101 (16.83) |

| Practicing anesthesiologist | 499 (83.16) |

| You have an experience of | |

| <5 years | 232 (38.66) |

| 5–10 years | 135 (22.5) |

| 10–20 years | 130 (21.66) |

| >20 years | 103 (17.16) |

| You are working at | |

| Autonomous Teaching Institute | 68 (11.33) |

| Government Medical College | 117 (19.50) |

| Private Medical College | 62 (10.33) |

| Corporate Teaching Hospital | 97 (16.16) |

| Government Non-teaching Hospital | 51 (8.51) |

| Private Non-teaching Hospital | 203 (33.8) |

| Others | 02 (0.33) |

| Do you fill surgical safety checklist routinely? | |

| Yes | 387 (64.5) |

| No | 212 (35.33) |

| Blank | 01 (0.16) |

| Who checks the anesthesia machine and safety equipment preoperatively? | |

| Technician or Nursing office | 343 (57.16) |

| Resident | 276 (46.0) |

| Consultant | 268 (44.66) |

| Who prepares the anesthesia related drug preoperatively? | |

| Technician or Nursing office | 225 (37.5) |

| Resident | 302 (50.33) |

| Consultant | 300 (50.0) |

| What are the monitoring available in your working setup for routine use | |

| Peripheral oxyhemoglobin saturation | 598 (99.66) |

| End-tidal carbon-di-oxide | 530 (88.33) |

| Non-invasive Blood Pressure | 593 (98.83) |

| Skin temperature | 357 (59.5) |

| Core temperature | 270 (45.0) |

| Minimum alveolar concentration | 325 (54.16) |

| Neuromuscular blockade testing/monitoring | 191 (31.83) |

| Bi-spectral Index | 193 (32.16) |

| Is Oxygen analyzer available in your anesthesia machine? | |

| Yes | 419 (69.83) |

| No | 180 (30.0) |

| Blank | 01 (0.16) |

| Is Anesthesia Gas analyzer available in your anesthesia machine/monitor? | |

| Yes | 339 (56.5) |

| No | 255 (42.5) |

| Blank | 06 (1.0) |

n: number, N: total number is 600.

Pre anesthetic preparations sub-grouped as per working set-ups and compared using Fisher's exact test, taking ATI as standard.

| Questions and options | ATI [N=68] | GMC [N=117] | P value | PMC [N=62] | P value | CTH [N=97] | P value | GNTH [N=51] | P value | PNTH [N=203] | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you fill surgical safety checklist routinely? | |||||||||||

| Yes | 48 (70.58) | 46 (39.31) | <0.0001 | 43 (69.35) | 1.000 | 92 (94.84) | <0.0001 | 21 (41.17) | 0.001 | 137 (67.48) | 0.763 |

| No | 20 (29.41) | 71 (60.68) | <0.0001 | 19 (30.64) | 1.000 | 04 (4.12) | <0.0001 | 30 (58.82) | 0.001 | 66 (32.51) | 0.763 |

| Blanks | 00 (00) | 00 (00) | – | 00 (00) | – | 01 (1.03) | 1.000 | 00 (00) | – | 00 (00) | – |

| Who checks the machine and safety equipment | |||||||||||

| Technician or Nursing office | 42 (61.76) | 39 (33.62) | 0.0002 | 30 (48.38) | 0.158 | 77 (79.38) | 0.014 | 28 (54.90) | 0.459 | 126 (62.06) | 1.000 |

| Resident | 51 (75) | 108 (92.30) | 0.001 | 38 (61.29) | 0.130 | 54 (55.67) | 0.013 | 11 (21.56) | <0.0001 | 14 (6.89) | <0.0001 |

| Consultant | 13 (19.11) | 20 (17.09) | 0.842 | 23 (37.09) | 0.030 | 44 (45.36) | 0.0005 | 25 (49.01) | 0.0007 | 142 (69.95) | <0.0001 |

| Who prepares the drug preoperatively? | |||||||||||

| Technician or Nursing office | 24 (35.29) | 22 (18.80) | 0.014 | 25 (40.32) | 0.590 | 51 (52.57) | 0.038 | 19 (37.25) | 0.849 | 85 (41.87) | 0.392 |

| Resident | 60 (88.23) | 107 (91.45) | 0.607 | 44 (70.96) | 0.016 | 63 (64.94) | 0.0009 | 10 (19.60) | <0.0001 | 18 (8.86) | <0.0001 |

| Consultant | 16 (23.52) | 22 (18.80) | 0.455 | 16 (25.80) | 0.839 | 51 (52.57) | 0.0002 | 35 (68.62) | <0.0001 | 158 (77.83) | <0.0001 |

n: number, N: total number, ATI: Autonomous Teaching Institutes, CTH: Corporate Teaching Hospital, GMC: Government Medical College, PMC: Private Medical College, GNTH: Government non-teaching hospital, PNTH: Private non-teaching hospital. Note. Two responders were from other category and is not included in the analysis.

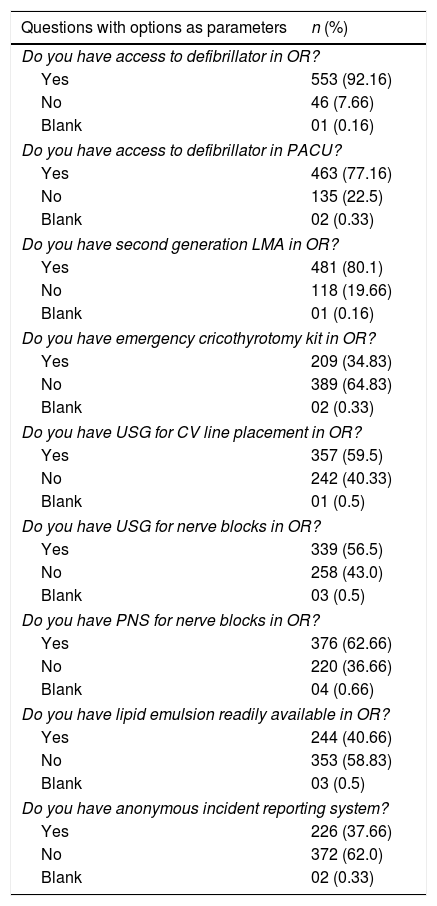

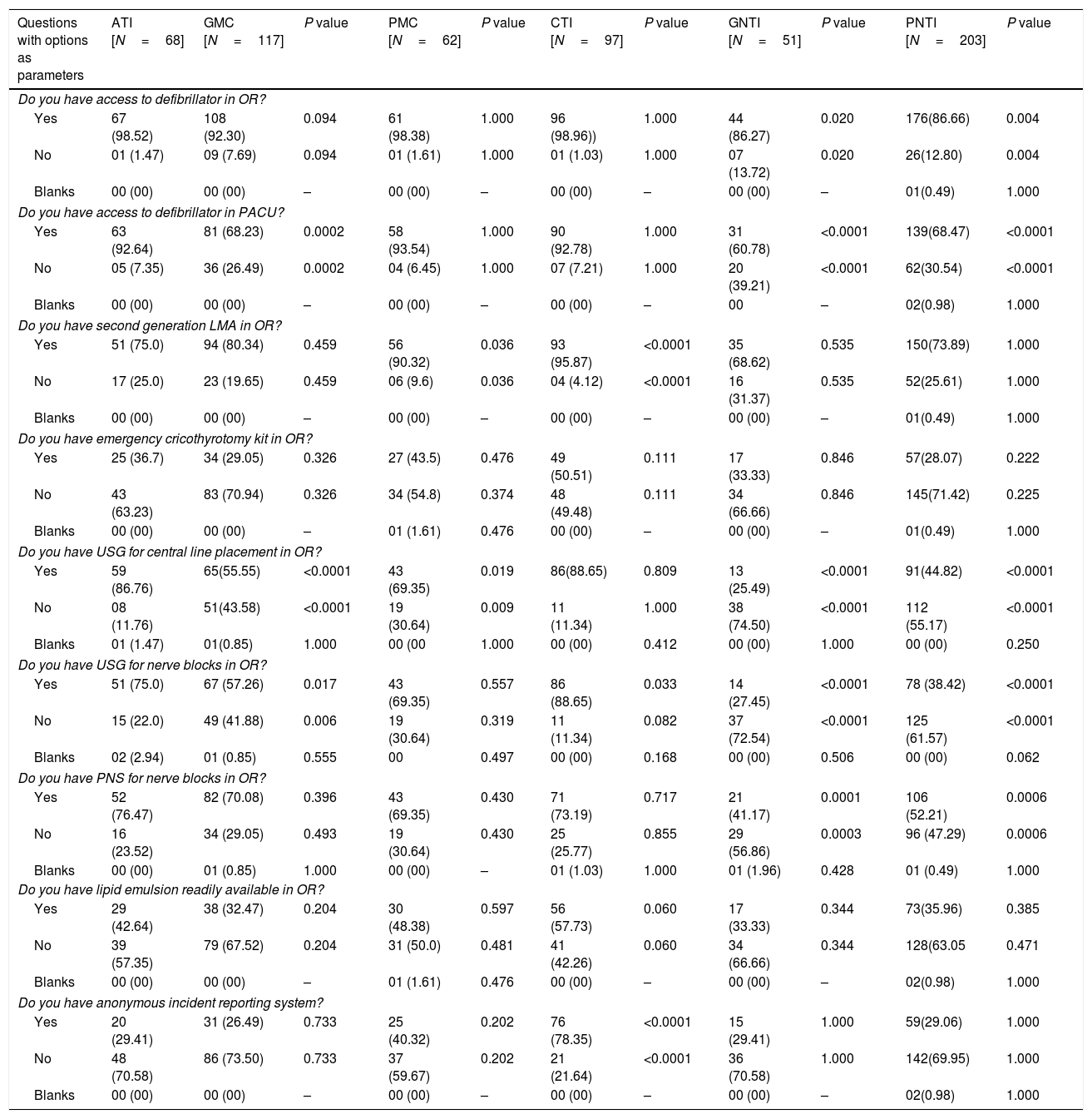

Ninety-two percent of the operation theater (OT) and 77% of the Post Anesthesia Care Unit (PACU) were having defibrillators, while second-generation laryngeal mask airway (LMA) was available to 80% of the responders. However, an emergency cricothyrotomy kit for the emergency front of neck access in difficult airway situations was available to only 34.8% responders. Advanced equipment like ultrasound machine (USG), and peripheral nerve stimulators (PNS) were also not available to nearly 50% of the responders (Table 3).

Availability of different equipment, medications and systems for patient safety among the entire cohort.

| Questions with options as parameters | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Do you have access to defibrillator in OR? | |

| Yes | 553 (92.16) |

| No | 46 (7.66) |

| Blank | 01 (0.16) |

| Do you have access to defibrillator in PACU? | |

| Yes | 463 (77.16) |

| No | 135 (22.5) |

| Blank | 02 (0.33) |

| Do you have second generation LMA in OR? | |

| Yes | 481 (80.1) |

| No | 118 (19.66) |

| Blank | 01 (0.16) |

| Do you have emergency cricothyrotomy kit in OR? | |

| Yes | 209 (34.83) |

| No | 389 (64.83) |

| Blank | 02 (0.33) |

| Do you have USG for CV line placement in OR? | |

| Yes | 357 (59.5) |

| No | 242 (40.33) |

| Blank | 01 (0.5) |

| Do you have USG for nerve blocks in OR? | |

| Yes | 339 (56.5) |

| No | 258 (43.0) |

| Blank | 03 (0.5) |

| Do you have PNS for nerve blocks in OR? | |

| Yes | 376 (62.66) |

| No | 220 (36.66) |

| Blank | 04 (0.66) |

| Do you have lipid emulsion readily available in OR? | |

| Yes | 244 (40.66) |

| No | 353 (58.83) |

| Blank | 03 (0.5) |

| Do you have anonymous incident reporting system? | |

| Yes | 226 (37.66) |

| No | 372 (62.0) |

| Blank | 02 (0.33) |

n: number, N: total number is 600, OR: operating room, PACU: Post-anesthesia Care Unit, CV: central vein, LMA: laryngeal mask airway, PNS: peripheral nerve stimulator, USG: ultrasonography.

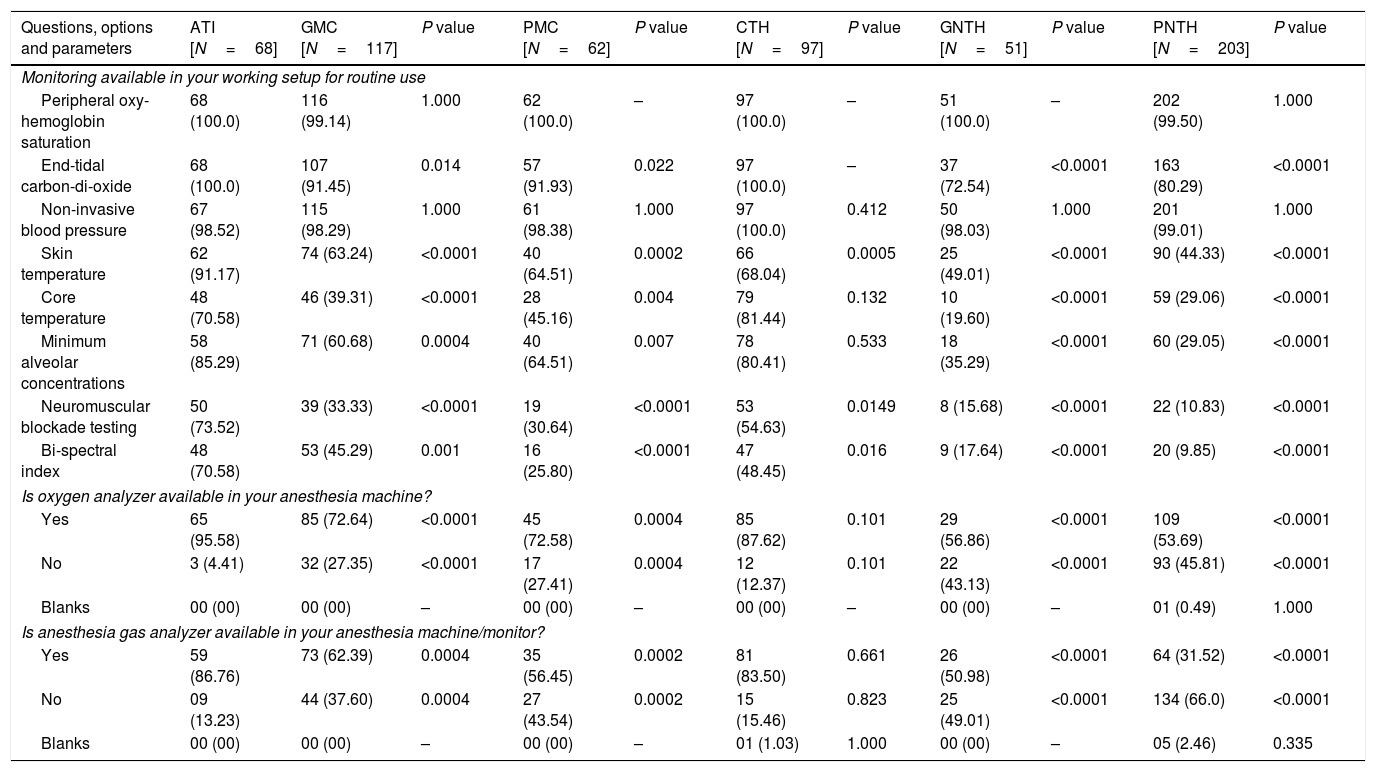

The ATIs had the highest percentages of availability of monitoring and devices, followed by the CTH. No statistically significant difference was found between ATI and CTH except for neuromuscular testing and Bi-spectral Index monitoring; CTH had slightly lower, P=0.01 (Table 4). Except for SpO2 and NIBP, other standard monitoring was significantly lower in the PMCs, GMCs, GNTH, and PNTHs as compared to both ATI and CTH (Table 4).

Availability and practice of standard and essential monitoring sub-grouped as per working set-ups and compared using Fisher's exact test, taking ATI as standard.

| Questions, options and parameters | ATI [N=68] | GMC [N=117] | P value | PMC [N=62] | P value | CTH [N=97] | P value | GNTH [N=51] | P value | PNTH [N=203] | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monitoring available in your working setup for routine use | |||||||||||

| Peripheral oxy-hemoglobin saturation | 68 (100.0) | 116 (99.14) | 1.000 | 62 (100.0) | – | 97 (100.0) | – | 51 (100.0) | – | 202 (99.50) | 1.000 |

| End-tidal carbon-di-oxide | 68 (100.0) | 107 (91.45) | 0.014 | 57 (91.93) | 0.022 | 97 (100.0) | – | 37 (72.54) | <0.0001 | 163 (80.29) | <0.0001 |

| Non-invasive blood pressure | 67 (98.52) | 115 (98.29) | 1.000 | 61 (98.38) | 1.000 | 97 (100.0) | 0.412 | 50 (98.03) | 1.000 | 201 (99.01) | 1.000 |

| Skin temperature | 62 (91.17) | 74 (63.24) | <0.0001 | 40 (64.51) | 0.0002 | 66 (68.04) | 0.0005 | 25 (49.01) | <0.0001 | 90 (44.33) | <0.0001 |

| Core temperature | 48 (70.58) | 46 (39.31) | <0.0001 | 28 (45.16) | 0.004 | 79 (81.44) | 0.132 | 10 (19.60) | <0.0001 | 59 (29.06) | <0.0001 |

| Minimum alveolar concentrations | 58 (85.29) | 71 (60.68) | 0.0004 | 40 (64.51) | 0.007 | 78 (80.41) | 0.533 | 18 (35.29) | <0.0001 | 60 (29.05) | <0.0001 |

| Neuromuscular blockade testing | 50 (73.52) | 39 (33.33) | <0.0001 | 19 (30.64) | <0.0001 | 53 (54.63) | 0.0149 | 8 (15.68) | <0.0001 | 22 (10.83) | <0.0001 |

| Bi-spectral index | 48 (70.58) | 53 (45.29) | 0.001 | 16 (25.80) | <0.0001 | 47 (48.45) | 0.016 | 9 (17.64) | <0.0001 | 20 (9.85) | <0.0001 |

| Is oxygen analyzer available in your anesthesia machine? | |||||||||||

| Yes | 65 (95.58) | 85 (72.64) | <0.0001 | 45 (72.58) | 0.0004 | 85 (87.62) | 0.101 | 29 (56.86) | <0.0001 | 109 (53.69) | <0.0001 |

| No | 3 (4.41) | 32 (27.35) | <0.0001 | 17 (27.41) | 0.0004 | 12 (12.37) | 0.101 | 22 (43.13) | <0.0001 | 93 (45.81) | <0.0001 |

| Blanks | 00 (00) | 00 (00) | – | 00 (00) | – | 00 (00) | – | 00 (00) | – | 01 (0.49) | 1.000 |

| Is anesthesia gas analyzer available in your anesthesia machine/monitor? | |||||||||||

| Yes | 59 (86.76) | 73 (62.39) | 0.0004 | 35 (56.45) | 0.0002 | 81 (83.50) | 0.661 | 26 (50.98) | <0.0001 | 64 (31.52) | <0.0001 |

| No | 09 (13.23) | 44 (37.60) | 0.0004 | 27 (43.54) | 0.0002 | 15 (15.46) | 0.823 | 25 (49.01) | <0.0001 | 134 (66.0) | <0.0001 |

| Blanks | 00 (00) | 00 (00) | – | 00 (00) | – | 01 (1.03) | 1.000 | 00 (00) | – | 05 (2.46) | 0.335 |

n: number, N: total number, ATI: Autonomous Teaching Institutes, CTH: Corporate Teaching Hospital, GMC: Government Medical College, PMC: Private Medical College, GNTH: government non-teaching hospital, PNTH: private non-teaching hospital. Note. Two responders were from other category and is not included in the analysis.

The CTH had significantly higher access to second-generation LMA for airway management even as compared to ATI (95.8% versus 75%; P<0.0001), but the availability of emergency cricothyrotomy kit was indifferent. While the PMCs were at par with the ATI except for USG availability, USG, PNS, Cricothyrotomy kit availability was significantly lower in the GMCs as compared to ATI (Table 5). Anonymous incident reporting was, however, very poor in all set-ups except for CTH (78.3%, P<0.0001 for almost all).

Availability of different equipment, medications and systems for patient safety among the different working set-ups and compared using Fisher's exact test, taking ATI as standard.

| Questions with options as parameters | ATI [N=68] | GMC [N=117] | P value | PMC [N=62] | P value | CTI [N=97] | P value | GNTI [N=51] | P value | PNTI [N=203] | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you have access to defibrillator in OR? | |||||||||||

| Yes | 67 (98.52) | 108 (92.30) | 0.094 | 61 (98.38) | 1.000 | 96 (98.96)) | 1.000 | 44 (86.27) | 0.020 | 176(86.66) | 0.004 |

| No | 01 (1.47) | 09 (7.69) | 0.094 | 01 (1.61) | 1.000 | 01 (1.03) | 1.000 | 07 (13.72) | 0.020 | 26(12.80) | 0.004 |

| Blanks | 00 (00) | 00 (00) | – | 00 (00) | – | 00 (00) | – | 00 (00) | – | 01(0.49) | 1.000 |

| Do you have access to defibrillator in PACU? | |||||||||||

| Yes | 63 (92.64) | 81 (68.23) | 0.0002 | 58 (93.54) | 1.000 | 90 (92.78) | 1.000 | 31 (60.78) | <0.0001 | 139(68.47) | <0.0001 |

| No | 05 (7.35) | 36 (26.49) | 0.0002 | 04 (6.45) | 1.000 | 07 (7.21) | 1.000 | 20 (39.21) | <0.0001 | 62(30.54) | <0.0001 |

| Blanks | 00 (00) | 00 (00) | – | 00 (00) | – | 00 (00) | – | 00 | – | 02(0.98) | 1.000 |

| Do you have second generation LMA in OR? | |||||||||||

| Yes | 51 (75.0) | 94 (80.34) | 0.459 | 56 (90.32) | 0.036 | 93 (95.87) | <0.0001 | 35 (68.62) | 0.535 | 150(73.89) | 1.000 |

| No | 17 (25.0) | 23 (19.65) | 0.459 | 06 (9.6) | 0.036 | 04 (4.12) | <0.0001 | 16 (31.37) | 0.535 | 52(25.61) | 1.000 |

| Blanks | 00 (00) | 00 (00) | – | 00 (00) | – | 00 (00) | – | 00 (00) | – | 01(0.49) | 1.000 |

| Do you have emergency cricothyrotomy kit in OR? | |||||||||||

| Yes | 25 (36.7) | 34 (29.05) | 0.326 | 27 (43.5) | 0.476 | 49 (50.51) | 0.111 | 17 (33.33) | 0.846 | 57(28.07) | 0.222 |

| No | 43 (63.23) | 83 (70.94) | 0.326 | 34 (54.8) | 0.374 | 48 (49.48) | 0.111 | 34 (66.66) | 0.846 | 145(71.42) | 0.225 |

| Blanks | 00 (00) | 00 (00) | – | 01 (1.61) | 0.476 | 00 (00) | – | 00 (00) | – | 01(0.49) | 1.000 |

| Do you have USG for central line placement in OR? | |||||||||||

| Yes | 59 (86.76) | 65(55.55) | <0.0001 | 43 (69.35) | 0.019 | 86(88.65) | 0.809 | 13 (25.49) | <0.0001 | 91(44.82) | <0.0001 |

| No | 08 (11.76) | 51(43.58) | <0.0001 | 19 (30.64) | 0.009 | 11 (11.34) | 1.000 | 38 (74.50) | <0.0001 | 112 (55.17) | <0.0001 |

| Blanks | 01 (1.47) | 01(0.85) | 1.000 | 00 (00 | 1.000 | 00 (00) | 0.412 | 00 (00) | 1.000 | 00 (00) | 0.250 |

| Do you have USG for nerve blocks in OR? | |||||||||||

| Yes | 51 (75.0) | 67 (57.26) | 0.017 | 43 (69.35) | 0.557 | 86 (88.65) | 0.033 | 14 (27.45) | <0.0001 | 78 (38.42) | <0.0001 |

| No | 15 (22.0) | 49 (41.88) | 0.006 | 19 (30.64) | 0.319 | 11 (11.34) | 0.082 | 37 (72.54) | <0.0001 | 125 (61.57) | <0.0001 |

| Blanks | 02 (2.94) | 01 (0.85) | 0.555 | 00 | 0.497 | 00 (00) | 0.168 | 00 (00) | 0.506 | 00 (00) | 0.062 |

| Do you have PNS for nerve blocks in OR? | |||||||||||

| Yes | 52 (76.47) | 82 (70.08) | 0.396 | 43 (69.35) | 0.430 | 71 (73.19) | 0.717 | 21 (41.17) | 0.0001 | 106 (52.21) | 0.0006 |

| No | 16 (23.52) | 34 (29.05) | 0.493 | 19 (30.64) | 0.430 | 25 (25.77) | 0.855 | 29 (56.86) | 0.0003 | 96 (47.29) | 0.0006 |

| Blanks | 00 (00) | 01 (0.85) | 1.000 | 00 (00) | – | 01 (1.03) | 1.000 | 01 (1.96) | 0.428 | 01 (0.49) | 1.000 |

| Do you have lipid emulsion readily available in OR? | |||||||||||

| Yes | 29 (42.64) | 38 (32.47) | 0.204 | 30 (48.38) | 0.597 | 56 (57.73) | 0.060 | 17 (33.33) | 0.344 | 73(35.96) | 0.385 |

| No | 39 (57.35) | 79 (67.52) | 0.204 | 31 (50.0) | 0.481 | 41 (42.26) | 0.060 | 34 (66.66) | 0.344 | 128(63.05 | 0.471 |

| Blanks | 00 (00) | 00 (00) | – | 01 (1.61) | 0.476 | 00 (00) | – | 00 (00) | – | 02(0.98) | 1.000 |

| Do you have anonymous incident reporting system? | |||||||||||

| Yes | 20 (29.41) | 31 (26.49) | 0.733 | 25 (40.32) | 0.202 | 76 (78.35) | <0.0001 | 15 (29.41) | 1.000 | 59(29.06) | 1.000 |

| No | 48 (70.58) | 86 (73.50) | 0.733 | 37 (59.67) | 0.202 | 21 (21.64) | <0.0001 | 36 (70.58) | 1.000 | 142(69.95) | 1.000 |

| Blanks | 00 (00) | 00 (00) | – | 00 (00) | – | 00 (00) | – | 00 (00) | – | 02(0.98) | 1.000 |

n: number, N: total number, ATI: Autonomous Teaching Institutes, CTH: Corporate Teaching Hospital, GMC: Government Medical College, PMC: Private Medical College, GNTH: government non-teaching hospital, PNTH: private non-teaching hospital, OR: operating room, PACU: Post-anesthesia Care Unit, LMA: laryngeal mask airway, USG: ultrasonography, PNS: peripheral nerve stimulator. Note. Two responders were from other category and is not included in the analysis.

The result of the present survey indicates that the facilities available and practices are variable across all the hospital set-ups of India. While the apex institutes like ATI, as well as a CTH, had better facilities and practices for patient safety, betterment scopes are still there even for these two set-ups. The Safe Surgery Saves Lives Study under the banner of the WHO showed that a structured checklist, with simple interventions spanning the perioperative period, could markedly improve surgical outcomes and even affect mortality.4 The point needs to be stressed that this effect was noted both across the developed and developing countries.4 Our present survey, however, shows poor compliance to the surgical safety checklist except for the CTH. The effect of anesthesia practice and the patient outcome remains unknown; however, provider errors continue to contribute to the perioperative events.5 Although anesthesia delivery systems (workstations and care-stations) have evolved a lot with many safety features, closed claim database analysis still indicates that failure to complete a full machine check leads to morbidity and mortality.5

Moreover, automated electronic checkout at the start, which is usually a standard in the present-day workstations, is not unfailing and allows circuit dysfunction to go unnoticed.6 Furthermore, most of the workstations also allow us to accept some dysfunction and thus proceed to leave a space for error to occur.6 The present survey indicates that the pre-anesthetic machine check-up was routine. However, it was mostly done by the technicians, nurses, and residents in teaching hospitals, leaving us to speculate about its complete functionality.

Expert opinion based on the current literature suggests that the postoperative morbidity and mortality can probably be improved by implementing evidence-based safety protocols, checklists, appropriate patient monitoring.7 The provision of appropriate life support measures takes precedence both during elective and emergency, and patient monitoring is intended for quality patient care. The ASA Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters recommends continual monitoring of the patient's oxygenation, ventilation, circulation, and temperature during all anesthesia procedures.8 The pulse oximetry, NIBP, electrocardiogram, inspired and expired oxygen, carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, and volatile anesthetic agent if used, airway pressure, PNS if neuromuscular blocking drugs used, and temperature for any procedure lasting more than 30minutes duration is considered as minimum monitoring for anesthesia by the AAGBI.9 The present survey, however, points toward a very poor availability and practice of basic standards monitoring modality except for the pulse oximetry. Even EtCO2 monitoring was lacking in many set-ups. On the contrary, EtCO2 monitoring for confirmation of correct placement of an endotracheal tube is a mandatory and highly recommended practice by the WHO-WFSA.10 A recent Indian survey on anesthesia gases and fresh gas flow indicates that the use of Nitrous Oxide is very much prevalent.11 The use of oxygen analysis as a measure to prevent and detect hypoxia or hypoxemic mixture delivery during Nitrous oxide-based anesthesia is recommended.9 However, the present survey indicates that the availability and the practice of monitoring of end-tidal oxygen and anesthesia gas concentrations were very poor; 50–75% of the GMCs, PMCs, and non-teaching hospitals of both public and private sectors did not have the facilities.

The Utstein formula for survival indicates that the survival of a patient depends on medical science, educational efficiency, and local implementation.12 It is therefore clear that only the advancement of medical science in terms of evidence-based medicine and knowledge of healthcare providers is not enough for patient safety and survival; local implementation of those evidence into practice is equally essential. The present survey shows a poor implementation of preventive strategies like the availability of second-generation supraglottic airways, USG for central venous catheterization, regional anesthesia, and PNS for guiding nerve blocks. Second generation LMA has been recommended as a mandatory content of difficult airway cart by the AIDAA.13 The Difficult Airway Society (United Kingdom) recommends second-generation devices to be available in all hospitals for both routine use and rescue airway management.14 Even the difficult airway algorithm of the ASA indicates multiple crucial roles for this simple, low-cost, and relatively readily available device.15 However, our survey indicates that this device is not even available in many of the teaching and tertiary level institutes and hospitals. Considering the airway as one of the most critical causes of anesthesia-related mortality and litigation, this result of the survey is worrisome not only from the patient safety point of view but also from the practice condition of the anaesthesiologists across the country. Similar results were also shown for the availability of lipid emulsion. Intravenous lipid emulsion is the proven, immediate, and priority regimen for the treatment for local anesthetic systemic toxicity, which has the potential benefit in-terms of even mortality.16 While local anesthetics are used by the anaesthesiologists day-in and day-out, in every corner of the country, lipid emulsion was available only to 40% of the responders.

As far as our information and knowledge, no such previous survey was done in India. A recent survey conducted in the Peoples Republic of China on the anesthesia quality and patient safety also indicates similar results, i.e., reduced availability and practice of intraoperative standard monitoring.17 The first-ever World Patient Safety Day was celebrated by the WHO on 2019 September 17, to establish patient safety as a global health priority. Our survey shows that a lot can be done toward improving patient safety by the anaesthesiologists, anesthesia societies, and administrations.

The present study, although, has adequate power with the 600 sample size, the number 600 represents only a minor part of the practitioners in a country like India having nearly 18000 anaesthesiologists. The cross-sectional surveys and questionnaire as a tool also have its limitations. Despite having these limitations, we believe that the responders were 100% honest in answering, and the survey puts a lime-light on the practice condition and patient safety-related issues in India. Although the survey asked about preoperative preparation, some relevant aspects such as the safe use of medication (labeling of high-risk medication, marking of routes of administration) are not explicitly addressed in the questionnaire. Furthermore, the questionnaire used is not previously validated one and data are not much stratified.

To conclude, patient safety in the perioperative period and anesthesia-related services for surgical patients in India is poor. Except for pulse oximetry and NIBP, the public and private sector non-teaching hospitals were lacking even for basic and minimum other standard monitorings too. The secondary level and non-teaching hospital lack a lot in this aspect in terms of patient-safety related equipment and practice, but, referral and top-level corporate and public sector teaching hospitals too have room for improvement. However, we need validation of this questionnaire and more surveys with larger sample.

Plagiarism check noteChecked using http://smallseotools.com/plagiarism-checker/ on 14th Nov 2019: 99% Unique. The 1% (one sentence) which is shown as plagiarized is actually a recommendation from a society which is duly cited.

CTRI Registration: Not applicable for an online survey as per the Clinical Trial Registry of India.

ContributionAll authors contributed in tool development, data collection, analysis, interpretation and manuscript draft preparation and revision. The corresponding author will act as guarantor.

FundingNone declared.

Conflicts of interestNone.

We acknowledge the help of Mrs. Shikha Srivastava, Research Assistant of Dr. Habib Md Reazaul Karim for her help in calculations and analysis. We also acknowledge the help of Prof. (Dr.) P.K. Neema, head of the department for giving us permission for conducting this survey. Lastly, we thank the responders for taking our survey.