This study aimed to determine the validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the “Parental Attitudes toward Childhood Vaccines” (PACV) scale.

Materials and methods: A two-stage observational validation study was conducted. A back-translation technique was used and then the scale was validated with a sample of 343 parents with children aged 0–72 months. The test–retest method, Cronbach's alpha coefficient, Split-half analysis, and item analysis methods were used to determine the reliability of the scale, factor analyses were run to determine construct validity. Explanatory Factor Analysis and Confirmatory Factor Analysis were applied to assess construct validity.

ResultsCronbach's alpha coefficient was measured as .84. The Spearman–Brown coefficient was .82 and the Guttman Split-half coefficient was .81. According to the item-total correlation and Cronbach's alpha values when the item was deleted, no item was deleted from the scale. The intraclass correlation coefficient between the test–retest measurements was .79. The three-factor structure consisting of 15 items explained 51.6% of the total variance. As a result of the confirmatory factor analysis, a sufficient fit of the model to the model proposed in the original version of the scale was evident (χ2/sd=2.214, RMSEA=.06).

ConclusionThe Turkish version of the PACV is a valid and reliable scale and can be used to identify parental attitudes toward childhood vaccines.

Este estudio tuvo como objetivo determinar la validez y la confiabilidad turca de la escala «Actitudes de los padres sobre las vacunas infantiles» (PACV).

Materiales y métodosSe llevó a cabo un estudio de validación observacional en dos etapas. Se realizó un procedimiento de traducción-retrotraducción y luego se validó la escala con una muestra de 343 padres con hijos de 0 a 72meses. El método test-retest, el coeficiente alfa de Cronbach, el análisis de mitades divididas y los métodos de análisis de ítems se utilizaron para determinar la confiabilidad de la escala, y se realizaron análisis factoriales para determinar la validez de constructo. Se aplicaron análisis factorial explicativo y análisis factorial confirmatorio para evaluar la validez de constructo.

ResultadosEl coeficiente alfa de Cronbach se midió como 0,84. El coeficiente de Spearman-Brown fue de 0,82 y el coeficiente de mitad dividida de Guttman fue de 0,81. De acuerdo con la correlación ítem-total y los valores alfa de Cronbach cuando se eliminó el ítem, no se eliminó ningún ítem de la escala. El coeficiente de correlación intraclase entre las mediciones test-retest fue de 0,79. La estructura de tres factores que consta de 15ítems explicó el 51,6% de la varianza total. Como resultado del análisis factorial confirmatorio, se evidenció un ajuste suficiente del modelo al modelo propuesto en la versión original de la escala (χ2/sd=2,214, RMSEA=0,06).

ConclusiónLa versión turca de la PACV es una escala válida y confiable, y puede usarse para identificar las actitudes de los padres sobre las vacunas infantiles.

Vaccination is one of the most valuable achievements of public health. The statement “No other method, including antibiotics, except for clean drinking water, has been as effective as vaccination in reducing mortality rates” emphasizes how important and valuable vaccines are for humanity.1 Thanks to the vaccination programs, catching communicable diseases in the program and related deaths have decreased significantly. Therefore, it is necessary to reach high vaccination rates with vaccination programs to successfully reduce the incidence of frequently encountered vaccine-preventable diseases and the disability and death associated with these ailments. Thus, the vaccinated person is protected from infectious diseases, and the whole society is indirectly protected by providing herd immunity with high vaccination rates.2

Worldwide 2–3 million deaths are prevented by vaccination each year. In 2018, around 86% of infants were vaccinated globally and protected against vaccine-preventable diseases. Despite this, 19.5 million infants worldwide are still at risk for vaccine-preventable diseases because they do not receive essential vaccines.3 To maintain vaccine programs is essential for ensuring healthcare quality.

Despite all these achievements of vaccination, vaccine rejection cases constitute a serious global problem in vaccine-preventable epidemics. The number of anti-vaccination families has been rising in recent years. In Turkey, the number of families refusing vaccination was around 1400 in 2014, which became more than 23,000 in 2017. If this surge continues, population immunity will likely deteriorate, and epidemics may occur in the following years.3 Despite all vaccination campaigns globally, an average of 1.5 million people die every year from vaccine-preventable diseases.4

According to the report published by the World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF, the definitions of vaccine hesitancy and vaccine refusal are different from each other. Vaccine refusal is the state of not accepting or not receiving all vaccines. The full definition of vaccine hesitancy was defined by the WHO Strategic Advisory Group on Immunization Experts, Vaccine Concern Working Group as follows: “Vaccination hesitation refers to a delay in accepting or rejecting vaccination despite the availability of vaccination services. Vaccine instability is complex and context-specific, varying with time, place, and vaccines. In addition, it is influenced by factors such as convenience, indifference, and trust.”.5,6

On the other hand, in a study, parents who were hesitant about vaccination were defined as parents who refused some but not all vaccinations, postponed, or hesitated to have a vaccination. These parents are more in number than those who reject vaccines entirely, and they are more likely to get information about vaccines from health providers, change their decisions, and be convinced. Therefore, identifying parents who are hesitant about vaccination and determining their attitudes toward vaccination is of essential importance in understanding and preventing increasing vaccination rejection. The “Parent Attitudes About Childhood Vaccines” scale (PACV) was developed to identify parents who are hesitant about vaccination and accurately assess parental vaccination hesitations. Parents’ attitudes and hesitations about vaccines can be revealed with this scale.7,8 Thus, it may be possible to identify parents who are hesitant about childhood vaccinations, investigate the factors affecting this situation, and initiate preventive studies. Since parents decide on childhood vaccinations, public health needs to reveal parents’ attitudes on this issue.

The PACV scale is a tool easy to use in clinical practice in order to evaluate parents’ attitudes for childhood vaccination. In Turkey, there is no validated scale to detect parents who are undecided about childhood vaccination. Primary health care institutions play an important role in screening parents in terms of attitudes that may help to conduct more qualified healthcare services. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the Turkish validity and reliability of the PACV scale in a primary healthcare setting.

MethodsStudy design and participantsThis study is a two stages observational validation study. It was carried out in Education Family Health Centers affiliated with Atatürk University Faculty of Medicine between August and December 2020. Before starting the study, permission was obtained from the Atatürk University Faculty of Medicine Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Number: B.30.2.ATA.0.01.00/343 Date: 26.06.2020). Furthermore, Prof. Douglas J. Opel, who developed the PACV scale, was contacted via e-mail, and permission was obtained.

The minimum necessary sample size was calculated as 240 when the Cronbach's alpha at 80% power was 80% at a 95% confidence interval. A sample of 354 parents with children aged 0–72 months included who applied to our Education Family Health Centers. Other inclusion criteria were not having problems understanding, reading, and writing Turkish, volunteered to participate in the study and filled out the questionnaire completely. Temporal consistency was measured in 161 parents from the first test who agreed to retest two weeks later.

Language adaptationTranslation-back translation procedure was performed. In the first stage, the questionnaire was translated into Turkish by two different individuals who spoke Turkish and English as their mother tongue. Instead of word-for-word translation, it was translated in a way that did not change the scale in terms of meaning, in accordance with the characteristics of the target language. These two translated scales were then culturally and lexically arranged. Finally, it was translated back into English by someone fluent in both languages to confirm that none of the items lost their meaning.

Data collection toolsThe PACV scale, consisting of 17 questions, was applied to the participants who volunteered to join the study. In addition, the participants were asked questions created by the authors, querying their sociodemographic characteristics and measuring their attitudes toward the vaccine. Participants were briefly informed by a written text about the purpose of the questionnaire and how it should be filled. Informed consent form was obtained from all parents.

The Parent Attitudes about Childhood Vaccines (PACV): The scale consists of 17 questions. The first two items ask whether the child was the firstborn and the degree of closeness with the child. The PACV starts from the third question and consists of 15 items and 3 subdimension. These subdomains are behavior, general attitudes, and safety efficacy. There are items 1 and 2 in the area of behavior, items 3, 4, 5, 6, 11, 12, 13, 14, and 15 in general attitudes, and items 7, 8, 9, and 10 in safety-effectiveness. Three different response styles were used for PACV items. These response forms are preferential responses with yes, no, I do not know (items 1, 2, and 11), a 5-point Likert scale (items 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, and 14), and an 11-point response scale (items 3 and 15). The PACV scale items are given in Table 1.

The Turkish version of PACV scale items.

| Item 1 | Hiç çocuğunuzun hastalık veya alerji dışındaki nedenlerle (mevsimsel grip veya domuz gribi (H1N1) aşıları hariç) aşılanmasını geciktirdiniz mi? |

| Item 2 | Hiç çocuğunuza hastalık veya alerji dışındaki nedenlerden dolayı (mevsimsel grip veya domuz gribi (H1N1) aşıları hariç) aşılatmama kararı verdiniz mi? |

| Item 3 | Önerilen aşı planına uymanın çocuğunuz için iyi bir fikir olduğundan ne kadar eminsiniz? |

| Item 4 | Çocuklar kendileri için gerekli olandan daha fazla aşı oluyor. |

| Item 5 | Aşıların önlediği hastalıkların çoğunun ciddi olduğuna inanıyorum. |

| Item 6 | Çocuğumun hastalanarak bağışıklık geliştirmesi aşı olmaktan daha iyidir. |

| Item 7 | Çocukların aynı anda daha az aşı almaları daha iyidir. |

| Item 8 | Çocuğunuzun bir aşının ciddi bir yan etkisinden etkilenebileceğinden ne kadar endişelisiniz? |

| Item 9 | Çocukluk aşılarından herhangi birinin güvenli olmayabileceği konusunda ne kadar endişelisiniz? |

| Item 10 | Bir aşının hastalığı önleyemeyeceğinden ne kadar endişelisiniz? |

| Item 11 | Bugün başka bir bebeğiniz olsaydı. önerilen tüm aşıları almasını ister miydiniz? |

| Item 12 | Genel olarak çocukluk çağı aşıları konusunda ne kadar tereddüt ediyorsunuz? |

| Item 13 | Aşılar hakkında aldığım bilgilere güveniyorum. |

| Item 14 | Aşılarla ilgili endişelerimi çocuğumun doktoruyla açıkça tartışabiliyorum. |

| Item 15 | Her şey düşünüldüğünde çocuğunuzun doktoruna ne kadar güveniyorsunuz? |

PACV, Parent Attitudes About Childhood Vaccines.

Evaluation of the Responses of the PACV Scale: The assessment scores of the scale are two points for hesitant answers, 0 points for unhesitating answers, and 1 point for “I’m not sure, or I don’t know” responses. Items 1 and 2, in which the answer “I don’t know” is considered missing data, are excluded when scoring, and 2 points are assigned to hesitant answers and 0 points to unhesitating answers for these items. After the scores of each item are given, they are added together to calculate the total raw score. Hence, if all questions were answered and items 1 and 2 were not considered missing data, the total raw score would be between 0 and 30. If there is at least one unanswered item or if item 1 or 2 is answered as “I don’t know” (missing data), the total raw score needs to be adjusted. E.g., if an unanswered item or one of the 1st or 2nd items is missing data, the total raw score takes a value between 0–28. If two questions are excluded as unanswered or missing data, the total raw score ranges from 0 to 26. Opel et al. calculated the total obtained raw score for items with missing values. They are converted to values between 0 and 100 according to the score conversion table using the simple linear calculation method. If the converted total score of the parent participating in the scale is below 50, the parent is categorized as having no hesitation; if it is 50 or above, it indicates a parent with hesitation.9

Statistical analysisSPSS 22.0 (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) and AMOS (Analysis of a moment structures) statistical package programs were used for the reliability and validity analyzes of the scale. The sociodemographic data of the participants were presented as mean±standard deviation (SD) or number (%). The scores obtained from the PACV scale were reported as mean±SD. Student t-test was used to compare numerical data between two independent groups, and a Chi-square test was used to compare categorical data. In the validity analysis, firstly, Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett sphericity tests were performed to determine whether the data were suitable for factor analysis and whether the items were correlated with each other. Then, Exploratory Factor Analysis and Confirmatory Factor Analysis were applied. Cronbach's alpha coefficient, split-half analysis, and Guttman Split-Half and Spearman–Brown coefficients were analyzed for reliability analysis. Test–retest was performed, and the intraclass correlation was checked. p<0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

ResultsCharacteristics of participantsOur study included 354 parents. Eleven questionnaires that were inappropriately filled were excluded from the study. In total, 343 questionnaires were analyzed. The mean age of the participants was 33.4±5.6 years. The mean age of the children of the participants was 18±16.8 months. Of the parents participating in the study, 76.7% (n=263) were mothers, 98% (n=336) were married, and 72.9% (n=250) were university graduates.

When questioned about the most frequently used sources of information about vaccines, 65.6% (n=225) stated that they got information from health institutions, 16.9% (n=58) from the internet, 15.7% (n=54) from written sources such as books, magazines, and articles, 1.2% (n=4) from their relatives or friends, and 0.3% (n=1) stated that they got information from the media organs such as radio and television.

The mean PACV raw score of the participants was 8.3±6.2 and ranged from 0 to 29 points. The mean converted PACV score of the participants was 27.7±20.9 and changed from 0 to 97. According to the PACV scores of the participants, 17.2% (n=59) had hesitations about childhood vaccination.

It was examined whether the participants had hesitations about vaccination according to their mean age, parental gender, and education level. Accordingly, no significant correlation was found between the stated characteristics and the childhood vaccine hesitancy (p>0.05). It was observed that there was a statistically significant difference between the mean monthly income of those with and without vaccine hesitation (p<0.05). A statistically significant correlation was found between the desire to have the vaccine and the hesitancy to be vaccinated when there is no obligation to have childhood vaccinations (p<0.05). It was determined that there was a significant relationship between the degree of being affected by the anti-vaccine news or information in the media and having a vaccine hesitation (p<0.05). There was a significant difference between the parents’ decision to delay childhood vaccinations and vaccination hesitancy (p<0.05) (Table 2).

Rotated components matrix after factor analysis.

| Rotated component matrix | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Items (PACV scale) | Factor | ||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Item 14 | 0.757 | ||

| Item 15 | 0.743 | ||

| Item 13 | 0.730 | ||

| Item 3 | 0.651 | ||

| Item 11 | 0.644 | ||

| Item 5 | 0.527 | ||

| Item 9 | 0.822 | ||

| Item 8 | 0.785 | ||

| Item 10 | 0.726 | ||

| Item 12 | 0.593 | ||

| Item 4 | 0.659 | ||

| Item 6 | 0.620 | ||

| Item 2 | 0.573 | ||

| Item 1 | 0.521 | ||

| Item 7 | 0.433 | ||

PACV, Parent Attitudes About Childhood Vaccines.

The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) coefficient was calculated as 0.876, and the Bartlett test of sphericity was also found significant (χ2=1489.839, p<0.05). Thus, it was seen that the scale was suitable for factor analysis.

As a result of the total amount of variance and factor analysis explained, the items were grouped in three subdimensions with an eigenvalue above 1.20, and the scale explained 51.6% of the total variance.

Rotation was applied to the factor analysis with the Varimax method, and the inter-item correlations were checked to determine the explanatory factor items. It was observed that PACV items were grouped under three factors. Items 3, 5, 11, 13, 14, and 15 were gathered under Factor 1, items 8, 9, 10, and 12 under Factor 2, and items 1, 2, 4, 6, and 7 under Factor 3. No item was left out (Table 3).

The characteristics of the parents.

| Vaccine hesitancy | No vaccine hesitancy | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Age (year) | 33.66 | 5.79 | 32.17 | 4.87 | 0.065* |

| Income level (Turkish Lira) | 9243.31 | 6311.10 | 7022.22 | 3586.01 | 0.000* |

| n | % | n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent | |||||

| Mother | 212 | 80.6 | 51 | 19.4 | 0.144** |

| Father | 71 | 89.9 | 8 | 10.1 | |

| Education level | |||||

| Primary school | 26 | 81.3 | 6 | 18.8 | 0.513** |

| Middle school | 41 | 77.4 | 12 | 22.6 | |

| High school | 213 | 83.9 | 41 | 16.1 | |

| Desire to be vaccinated when there is no obligation to vaccinate | |||||

| I would | 247 | 87 | 8 | 13.8 | 0.000** |

| Not sure | 32 | 11.3 | 18 | 31 | |

| I would not | 5 | 1.8 | 32 | 55.2 | |

| The level of influence by anti-vaccine news in the media | |||||

| 1–5 score | 224 | 79.4 | 58 | 20.6 | 0.000** |

| 6–10 score | 27 | 46.6 | 31 | 53.4 | |

| History of delayed vaccination | |||||

| Yes | 11 | 39.3 | 17 | 60.7 | 0.000** |

| No | 269 | 87.3 | 39 | 12.7 | |

SD, standard deviation.

** Statistically significant.

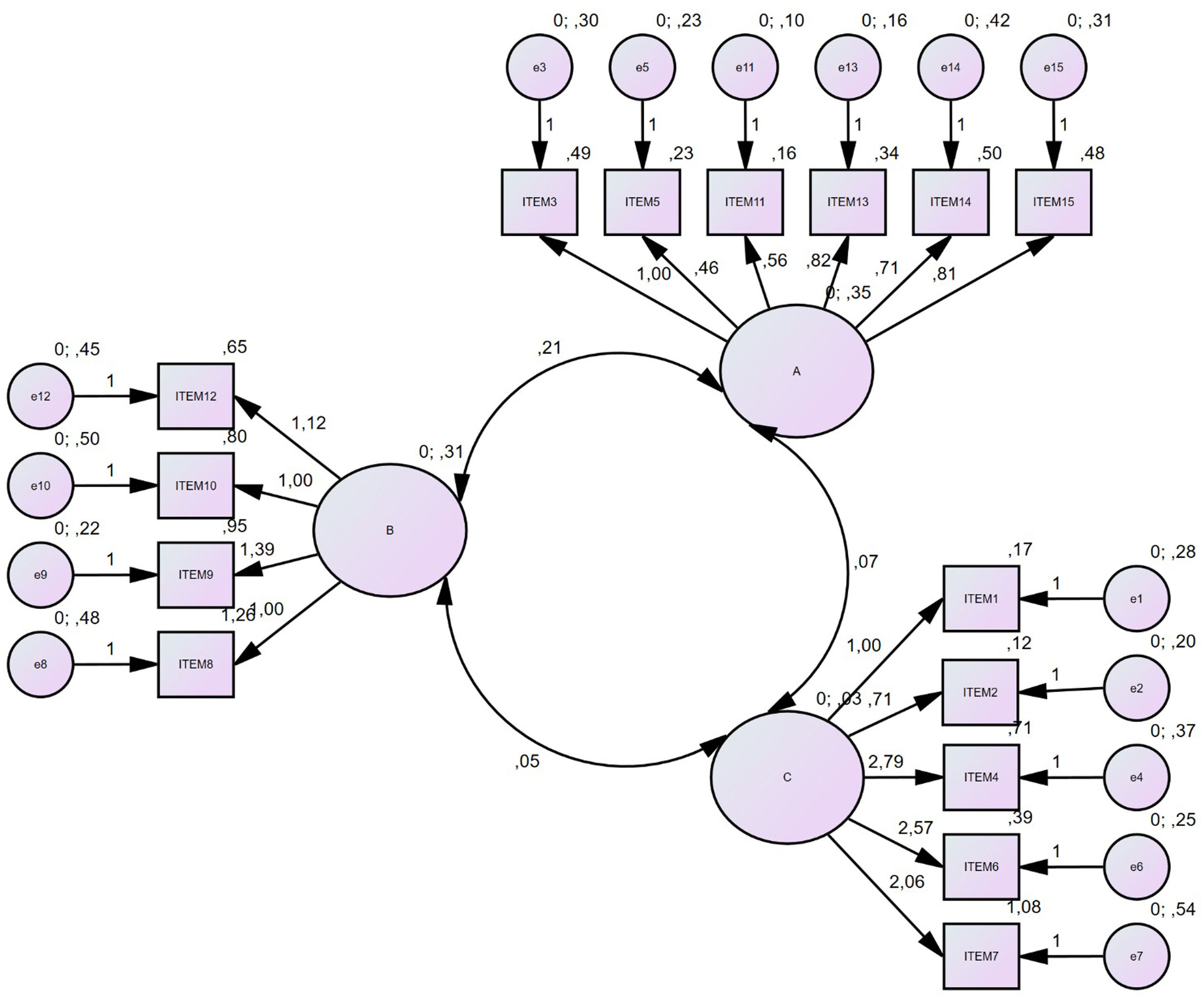

The first-level CFA model and parameter estimates created as a result of confirmatory factor analysis using the AMOS program to confirm the factor structures and their relationships with the items previously defined for the original scale are shown in Fig. 1. According to the CFA model, a total of 6 items (3, 5, 11, 13, 14, and 15) were in the general attitudes (A) subdomain, 4 items8–10,12 were in the safety-effectiveness (B) subdomain, and 5 items (1, 2, 4, 6, and 7) were observed to accumulate in the behavior (C) subdomain. Considering the importance of the item contributions to the CFA model, it was observed that each item contributed significantly to the formation of the dimensions (p<0.05).

When the goodness-of-fit analysis results of the first level CFA model were examined, it was seen that the sample model was compatible with the original structure of the study, and the model was significant (χ2/sd=2.214, RMSEA=0.06) (Table 4).

Predicted goodness of fit reference values for Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and analysis results.

| Indexes | Reference value | Measurement | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good fit | Acceptable fit | |||

| CMIN/DF | 0<χ2/sd≤3 | 3<χ2/sd≤5 | 2.214 | Good fit |

| CFI | 0.95<CFI≤1 | 0.90≤CFI≤0.95 | 0.927 | Acceptable fit |

| RMSEA | 0≤RMSEA≤.05 | .05<RMSEA≤.08 | 0.060 | Acceptable fit |

| TLI | 0.95≤TLI≤1 | 0.90≤TLI<0.95 | 0.900 | Acceptable fit |

| IFI | 0.95≤IFI≤1 | 0.90≤IFI<0.95 | 0.929 | Acceptable fit |

CMIN/DF, Chi-Square/degree of freedom; RMSEA, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; CFI, Comparative Fit Index; TLI, Trucker-Lewis Index; IFI, Incremental Fit Index (Increasing fit index).

The Cronbach's alpha coefficient was calculated as 0.84. Cronbach's alpha was 0.56, 0.80, and 0.78 for behavior, general attitudes, and safety-efficacy domains, respectively. The Split half analysis showed that the Unequal Length Spearman–Brown coefficient was calculated as 0.82 and the Guttman Split-Half coefficient as 0.81. When any items were removed from the scale, the Cronbach's alpha value varied between 0.82 and 0.84. In test–retest measurements, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), which indicates temporal consistency and reliability, was calculated as 0.79.

DiscussionIn this study, it has been shown that the Turkish version of the PACV is a valid and reliable scale that can be used to identify parents’ attitudes about childhood vaccines in the Turkish population. This scale, which was developed by Opel et al. in 2011, is a scale for identifying parents who are hesitant about vaccination and was defined by the authors as a valid and reliable tool.8

In our study, it was determined that 17.2% of the participants had hesitations about vaccination. Considering the publications in the literature in which vaccine hesitancy was determined using the PACV scale, it is seen that this rate varies between 7 and 35%.8–12 It is thought that these differences in vaccine hesitancy rates between the studies are due to the different cultures and environments of the populations (development level of the countries, rural or urban region, differences in the health institution where the study is conducted, etc.).

Our study examined the relationships between the participants’ socio-demographic characteristics and their hesitancy about vaccination. From the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants, only the relationship between income level and vaccine hesitancy was found, and it was observed that the participants with low-income levels had high hesitations about vaccination. No correlation was found between the age, gender, and educational status of the participants and their hesitancy about immunization. Research indicates that the relations between the participants’ socio-demographic characteristics and the vaccine hesitancy are pretty different from each other.11–14 This relationship is strongly influenced by the existing differences between cultures and populations, and very different results may emerge in this context in cross-cultural adaptation studies.

To see the discrimination of the PACV scale in parents hesitant about vaccination, the relationships between some of the participants’ attitudes and their hesitations were examined. It has been determined that vaccination hesitancy is significantly associated with the vaccination status when vaccination is not compulsory, the level of being affected by anti-vaccination news in the media, and the situation of not having or delaying childhood vaccinations in the past. Accordingly, it has been observed that parents who are hesitant about vaccination are less likely to be vaccinated when vaccination is not compulsory, the level of being affected by anti-vaccine news in the media is higher, and the statements of not having or delaying childhood vaccinations in the past are more prominent. When the literature is examined, it has been seen that parents’ attitudes are indeed highly related to vaccination hesitancy.15–17 These results provide essential clues showing that the scale can really measure the phenomenon to be measured and that it is a valid scale.

In our study, explanatory and confirmatory factor analyses were applied together to determine the scale's construct validity. With the KMO coefficient value above 0.80 and the Bartlett sphericity test being significant, it can be concluded that the scale can effectively measure the phenomenon, there is a correlation between the variables, and the study is highly suitable for factor analysis.18,19

The variance explained in the scales should explain at least 50% of the total variance. If the variance explains less than 50%, the representative ability cannot be claimed When the factor analysis results were evaluated in our study, it was deemed appropriate to collect the scale under three factors, and the explained variance explained 51.6% of the total variance. Therefore, along with the validity and reliability study of the original PACV scale, it was decided to collect the scale under three factors, and the explained variance percentages were over 50%.8,20,21

When the rotated components matrix table was examined in our study, items 3, 5, 11, 13, 14, and 15 were gathered under Factor 1, items 8, 9, 10, and 12 under Factor 2, and items 1, 2, 4, 6, and 7 under Factor 3. No item was left out. As a result, most of the items were combined under the same factors similar to the original structure. Thus, it was decided to make the naming similar to the original scale. While items collected in Factor 1 were associated with the “general attitude” subdomain of the original scale, items under Factor 2 were associated with the “safety-effectiveness” dimension, and items under Factor 3 with the “behavior” subdomain of the original scale. The 4th and 6th items in the general attitudes domain of the original scale were transferred to the behavior domain, while the 12th item was transferred to the safety-effectiveness dimension. Additionally, item 7 in the subdomain of safety-effectiveness was included in the behavior dimension.8 A similar situation was observed in cultural adaptation studies of the PACV scale, in which psychometric analyzes were made, and the items were grouped under different subdomains.20,21

According to the sample size of our study, factor-loading values should be at least 0.30 to talk about construct validity.22,23 In our study, all factor loading values were higher than 0.30, and it is seen that the scale has construct validity by looking at factor loading values.

As a result of CFA, it was determined that the model fit was good according to the theoretical structure obtained and this model's goodness of fit indexes. When we look at the goodness of fit indices, CMIN/DF, RMSEA, and CFI values, which provide more reliable information in terms of model fit, are the most commonly used and accepted indexes in studies.24,25 As a result, with these fit indices, it was revealed that the model had a good fit with the original factor structure, and it was determined that the scale had construct validity. When we look at the studies in the literature, CFA was not performed in most studies, including the original research of the PACV scale, and CFA was recommended by many authors.8,21 One of the strengths of our study is that CFA, which is recommended to be done in cultural adaptation studies, was carried out.

In our study, the overall Cronbach's alpha value was found to be 0.84. Since the value is above 0.70, it is concluded that the scale is highly reliable and can be used in population screenings for the applied population.26,27 In general, it is understood that the general Cronbach's alpha value of the scale is at a high-reliability level, similar to our study and the previous adaptations of the PACV scale to other languages.10,11,21 When we look at the internal consistency coefficients evaluated for the subdomains in other studies, as in our study, the alpha coefficients of the behavior sub-domain were relatively low compared to the coefficients of the other domains.20,21 In our study, although the Cronbach alpha value of the behavioral subscale was lower than that of the other subscales, it was still considered reliable. As a result of the split-half analysis, the Spearman–Brown and Guttman Split-Half coefficients were above 0.80, as the total Cronbach alpha coefficient for the scale, and these coefficient values showed that the measurements were highly reliable.28 The test–retest analysis we conducted to evaluate the temporal consistency of the scale showed that the ICC value was higher than 0.75, the scale was reliable, and the temporal consistency was very good.21 When we compared with other studies in which test–retest analysis was performed, it was seen that the temporal consistency of the scale was very good.20,21

The corrected item-total correlation coefficients in the item analysis and the changes in the total Cronbach's alpha value of the scale were evaluated when the item was deleted, it was not necessary to remove any item from the scale. Only the item-total correlation coefficient of the second item of PACV was low, and this item was not removed from the scale because there was no significant increase in the total Cronbach's alpha value when the item was deleted. In a study conducted in Malaysia, PACV items 1 and 2 were not included in the psychometric evaluation, considering that there were questions about the vaccination history and that there might be a recall problem. Despite this, it was not removed from the scale as it was considered an essential item in identifying parents with hesitations about vaccination, and it was left as a demographic question. In addition, item 5, “I believe that most of the diseases prevented by vaccines are serious,” was excluded from the scale because the item-total correlation was low. Also, it was not statistically significant in differentiating vaccine hesitancy, based on another study.21 In a study conducted in Turkey, the item-total correlation coefficients of the 7th and 14th PACV items were low, and Cronbach's alpha values for these two items increased significantly when the item was deleted. Despite this, no item was removed from the scale; it was emphasized by the researcher that these items should be interpreted carefully.20 The reason for these different analysis results may be due to differences between cultures and populations. When the cross-cultural adaptation studies on various subjects are examined, it is seen that there may be different analysis results between the works and original studies.29,30

Our study is valuable because it is conducted in Family Health Centers, where childhood vaccinations are performed. One of the advantages of our study is that, in addition to the comprehensive Explanatory Factor Analysis performed to determine the validity of our study, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (which was suggested to be done in cultural adaptation studies and was not performed in previous studies) was also carried out. However, since the study was done in a few units affiliated with training family health centers and the sample size was limited, there is also a limitation concerning representation of the general population.

ConclusionThe Turkish version of the PACV scale is a valid and reliable tool that can be used in population screenings to identify parents who are hesitant about vaccination. As a result of the comprehensive analyses, it was determined that the scale's measurement skill, internal consistency, and temporal consistency were sufficient. The lack of a scale to be used in Turkey to identify vaccine-hesitant parents has been a substantial need in this area. Parents who are hesitant about vaccination are prone to both vaccine acceptance and vaccine rejection. If parents with vaccine hesitancy are detected, healthy doctor-patient communication can be established to relieve parents’ concerns and prevent the process from resulting in vaccine rejection. In addition, it is recommended to investigate the factors that may cause vaccine hesitancy in different populations with the PACV scale.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.