The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were introduced by the UN to protect and improve the environment and society. All UN Member States adopted this set of 17 interlinked global goals in 2015 as part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and covered a broad range of social, economic, and environmental development issues. The SDGs emphasize the interconnectedness of all aspects of development, recognizing that progress in one area often relies on progress in others. Some SDGs are reduced resource consumption, waste control, recycling promotion, and pollution reduction (United Nations Development Program, 2024). Overall, the SDGs provide a universal framework for countries to follow on their journey toward sustainable development, ensuring that the benefits of progress are shared globally and equitably. However, while some voices have questioned the excessive consumption and disproportionate use of resources, others support an increase in general consumption to improve living conditions worldwide (Kumar & Kumar 2016; Quoquab & Mohammad, 2017). This dichotomy persists today, leading to questions about what drives individuals to have different consumption attitudes and value organizations’ initiatives differently (Hosta & Zabkar, 2021).

Standards and guidelines have been set to address the environmental safety of products and services (Kumar & Barua, 2022) and align business strategy with the SDGs, and organizations have relied on sustainability reporting to communicate their commitment to the UN 2030 Agenda (Dinçer et al., 2024). With a comprehensive understanding of the connections among sustainability disclosure standards, organizations can tactically prioritize their reporting efforts, cater to the varied needs of stakeholders, and uphold their legitimacy (Dinçer et al., 2024). However, consumer behavior must also be considered to achieve the SDGs. The concept of responsible consumption behavior suggests that consumers have a significant role not only in reducing waste but also in deciding which products to buy and choosing sustainable market offers (Nangia et al., 2024).

The growing recognition of environmental issues and the need for sustainable solutions have intensified the focus on adopting a more sustainable consciousness among individuals (Trudel, 2019). Consequently, sustainable consumer behavior (SCB) has gained considerable attention as individuals increasingly recognize the importance of their consumption choices in shaping environmental outcomes. However, it remains unclear how different factors affect consumer behavior (Essiz & Mandrik, 2022) or how this knowledge flows into firms’ decision-making processes (Couto et al., 2016). Since the seventies, firms have been pushed to adopt sustainable approaches; hence, several models and policies have been developed. Many firms pursue sustainability because of its potential for long-term benefits, risk management, and positive impacts on the environment and society, but they tend to face challenges because not all consumers are aware of or prioritize sustainable products (Casalegno et al., 2022; Hosta & Zabkar, 2021). Calderon-Monge et al. (2020) noted that the analysis of SCB can be a source of business opportunities and unveil practices that can and should be adopted by firms to enhance the value of their sustainable approaches in the eyes of consumers.

The attitude–behavior gap in sustainability documents the phenomenon in which individuals express positive attitudes toward sustainability and environmental protection but fail to consistently translate these attitudes into sustainable behaviors. SCB is influenced by a combination of psychological, social, economic, and contextual factors. By understanding these drivers, businesses, policymakers, and educators can formulate strategies to promote and support SCB and ultimately advance environmental and social goals. Thus, the present work contributes to a deeper understanding of SCB by adopting two approaches following the structure proposed by Milfont and Markowitz (2016). Study 1 uses data derived from a survey conducted by Eurobarometer (n = 27,498) of citizens from the 28 EU countries to highlight the differences found in common policy areas. Study 2 focuses on Portugal and a specific sector, hospitality, and uses data taken from an online survey (n = 357). Thus, our work advances the theoretical discourse on SCB by elucidating the complex interplay among economic development, environmental attitudes, and actual behavior.

The remainder of this paper provides a theoretical background, followed by the methods and approaches applied in Studies 1 and 2. Subsequently, the study's implications, including limitations, are discussed. Finally, the conclusions are presented.

Theoretical backgroundSCB is influenced by a combination of factors. Environmental awareness and knowledge can motivate sustainable choices; however, personal values and beliefs based on a sense of responsibility or ethical considerations can also drive sustainable behavior. Social norms and peer influence are strong motivators, along with the belief that one's actions can make a difference. Other SCB drivers include financial considerations, convenience, accessibility, trust in brands, policies, regulations, innovations, media coverage, and advertising (Calderon-Monge et al., 2020; Hosta & Zabkar, 2021). The attitude–behavior gap found in sustainability practices may arise from consumers’ lack of specific knowledge, established habits, or the perceived inconvenience of available sustainable choices. Psychological aspects such as skepticism and not recognizing that unsustainable choices harm the environment and society in addition to sustainable behavioral inertia and certain cultural and social norms deeply rooted in consumers’ minds can lead to disengagement and inaction (Casalegno et al., 2022; Khan, Mehmood et al., 2024; Kwangsawad & Jattamart, 2022).

Sustainable consumer behaviorSCB is a complex and evolving field of research that is examined from both demand- and supply-side perspectives (Kostadinova, 2016; Milfont & Markowitz, 2016; Trudel, 2019). It refers to the choices and actions of consumers that prioritize the conservation and responsible management of resources to minimize the negative impact on the environment and society, both in the present and for future generations. As noted by Milfont and Markowitz (2016), empirical studies have explored various methods and theories to understand SCB, ranging from a macro perspective to micro- or individual-level analyses (see Fig. 1).

Multilevel model approach to SCB (adapted from Milfont & Markowitz, 2016).

Sustainable consumption covers a broad array of actions ranging from buying ecofriendly products to reducing water usage in homes and communities. Previous studies have typically focused on identifying the drivers of such behaviors at the individual, broader group, and societal levels. However, these behaviors are likely influenced by a combination of factors operating at different levels (Quoquab & Mohammad, 2017). Thus, understanding SCB requires a comprehensive grasp of the factors influencing individuals’ decisions related to sustainability at these various levels. Luchs and Mooradian (2012, p. 129) described consumer attitudes and behaviors as being shaped by environmental, social, and economic factors, encompassing diverse practices that potentially touch nearly every aspect of daily life. Studies have shown that environmental attitudes markedly influence consumer behavior. Gadenne et al. (2011) found that energy-saving actions are affected by environmental beliefs and attitudes and influenced by both intrinsic and extrinsic environmental motivators as well as social norms and the community. Similarly, Leonidou et al. (2010) identified factors such as collectivism, a forward-looking approach, political engagement, ethical principles, and adherence to laws as determinants of consumer attitudes and behaviors toward the environment.

Milfont and Markowitz (2016) posited that consumer behavior, particularly in the context of sustainability, is a multifaceted process influenced by a combination of individual, household, regional, and national factors. SCB specifically refers to consumption patterns aiming to minimize environmental impacts and promote social well-being. These behaviors are driven by a complex interplay of personal attitudes, household dynamics, local infrastructure, and overarching national policies and cultural norms. Embodying this definition are behaviors such as purchasing ecofriendly products, using renewable energy, and seeking goods produced with minimal environmental impact (Testa et al., 2021). Environmental knowledge, fundamental to the search for ecofriendly products, has also been shown to raise consumer environmental awareness significantly (Wang et al., 2022) and is evident in pro-environmental behaviors (Chang & Wu, 2015; Goh & Balaji, 2016; Tan, 2023). Taufique et al. (2017) and Fraj-Andrés and Martínez-Salinas (2007) found that higher levels of environmental knowledge are associated with more positive attitudes toward the environment, which in turn drive pro-environmental consumer behavior.

However, Gupta and Ogden (2006) highlighted the gap between environmental attitudes and behavior, suggesting that the relationship can be strengthened by consumer involvement and perceived effectiveness. Moreover, White et al. (2019) recalled the often-observed attitude–behavior gap in the realm of SCB, considering that despite consumers expressing positive attitudes toward ecofriendly behaviors (Trudel & Cotte, 2009), such attitudes do not align with actual sustainable practices (Trudel, 2019), which could be explained by their lack of knowledge and/or concern about sustainability issues (Liu et al., 2020) and the costs associated with this behavior (White et al., 2019).

Guided by the claim in the literature that consumer behavior evolves across eras and differs between countries, Quoquab and Mohammad (2020) explored works published between 2000 and 2020 and noticed that studies on sustainable consumption primarily originated from developed nations, including the United Kingdom, the United States, Denmark, Spain, the Netherlands, Germany, and Belgium, and that their outcomes were similar. As few studies have compared the attitude–behavior gap among countries, our first hypothesis is fundamental, following the macro approach of Milfont and Markowitz (2016), and relates to the similarities observed among countries regarding the impact of environmental attitudes and concern on consumer behavior.

H1

The attitude–behavior gap is similar among EU countries.

Several theoretical models and scales offer valuable insights into this complex phenomenon, with the most frequently employed being the theory of planned behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, 1991), value-belief-norm theory (Stern et al., 1999), and theory of social identity (Tajfel & Turner, 2004). Moreover, Unnithan (2020), in an in-depth literature review assessment, identified the TPB and other related theories as key foundations, whereas McDonald et al. (2012) emphasized the importance of a sociological, contextual approach to consumption behaviors and lifestyles. Abdulrazak and Quoquab (2018) introduced a self-deterministic approach, highlighting the role of communal links in motivating sustainable consumption. These diverse perspectives underscore the complexity of SCB and the need for a multifaceted understanding.

The sustainability dilemma from the consumer's perspectiveConsumer behavior has been a driving force behind the adoption of green practices by businesses. The goal to increase consumer awareness and preferences for environmentally friendly products has compelled companies to innovate and offer sustainable options (Al-Qudah et al., 2023). Consumer demand for ecofriendly products and services pressures businesses to invest in green technologies and develop products that meet ecofriendly standards. Consumers are more likely to incorporate sustainability into their buying behavior when they perceive it as effective (Al-Qudah et al., 2023; Gupta & Ogden, 2006), which presents a business opportunity for firms to align their strategies with consumer needs (Calderon-Monge et al., 2020). Evidence shows that a firm's sustainability exposure and environmental responsiveness significantly influence green consumer behavior (Wossen Kassaye, 2001). However, the consumer attitude–behavior gap still challenges firms deciding whether to adopt sustainable practices (Couto et al., 2016; Wossen Kassaye, 2001) because consumers may not fully understand these firms’ investments.

A paradox exists between profitability and sustainability, which may influence consumer perceptions of a brand or firm's sustainability efforts. Large brands face this challenge more often than smaller brands, as their profit motives are more evident and result in a supposedly less authentic approach to sustainability issues (Wallach & Popovich, 2023). Regarding how firms can make sustainability strategies more effective, van Zanten and van Tulder (2021) suggested that managing the linkages between the SDGs allows firms to simultaneously target multiple goals while reducing the risk that contributing to one SDG undermines progress on another. Authenticity is a key aspect for consumers in recognizing a brand's or a firm's sustainability efforts, even when they are not aligned with the firm's values. Brands or firms must be clear and consistent in their sustainability efforts and motivations to be acknowledged as being sustainable (larger brands must be more authentic and committed than smaller brands) (Wallach & Popovich, 2023).

Consumer-driven demand has influenced corporate strategies for fostering sustainable behavior as a key differentiator in competitive markets. Stakeholder pressures, including those from investors, suppliers, and regulatory bodies, encourage businesses to integrate green innovation into their operations. This illustrates the profound impact of consumer behavior on the evolution of green business practices (Viglia & Acuti, 2023; Yu et al., 2022).

The sustainability dilemma from the firm's perspectiveFirm managers are somehow forced to follow a global shift toward sustainability, taking on their role in the quest for sustainable performance and the safeguarding of the ecosystem (Edwards, 2021; Khan et al., 2023). Sustainable growth strategies must be based on social-ecological growth rather than exclusively on economic growth strategies, where the growth and development of people within a flourishing social-ecological setting is the purpose of a sustainable business (Edwards, 2021). Environmental concern can be addressed through green operations, marketing, and accounting. Additionally, through green leadership and human resource management, individuals and organizations can be influenced to realize a vision of long-term ecological sustainability and green behavior (Khan et al., 2023).

The evolution of business practices toward the adoption of green innovation has undergone several critical stages. Initially, businesses adopted green practices primarily to comply with environmental regulations and mitigate public scrutiny. This phase entailed basic environmental measures such as waste management, pollution control, and energy conservation (Ahmed et al., 2022). As the strategic importance of sustainability became apparent, businesses began integrating green practices into their operational and strategic frameworks. The second stage involved developing green products and processes, implementing green supply chain management, and investing substantially in green research and development. This led companies to recognize green innovation as a critical tool for achieving long-term sustainability and competitive advantages (Dang & Wang, 2022).

In the latest stage of evolution, businesses have adopted a holistic approach in which sustainability is deeply embedded in their organizational culture and strategic decision-making processes. This involves the systematic development and implementation of green intellectual capital, which encompasses green human, structural, and relational capital. The focus is on creating sustainable value for all stakeholders, enhancing brand reputation, and ensuring long-term business success (Madzík et al., 2024). Advanced artificial intelligence tools (Khan, Acuti et al., 2024) and comprehensive scientific mapping have enabled companies to explore and categorize green innovations more effectively and identify key areas for future research and development. The integration of these practices indicates a mature approach to sustainability in which environmental responsibility is a core component of business strategies (Viglia & Acuti, 2023).

New brands have emerged as environmentally friendly, which puts pressure on dominant (or large) brands to engage in sustainable practices and challenges them to be recognized by consumers for these efforts (Wallach & Popovich, 2023). Consumers perceive and value a brand's authenticity and this intangible asset has become increasingly significant in consumer decision-making (Pine & Gilmore, 2007; Wallach & Popovich, 2023). According to Gielens et al. (2018), from a marketing perspective, sustainability initiatives are usually focused on the product (i.e., materials, processes, resources used, and recyclable characteristics) and consumer responses to the product. Consumers tend to value companies that provide more information about the environmental impacts of their products and that clearly state their sustainability efforts (Wallach & Popovich, 2023).

An increasing number of companies engage in sustainability reporting. Some are setting ambitious environmental goals and taking further steps with sustainability-minded efforts (George & Schillebeeckx, 2021). Corporate sustainability disclosures include all relevant economic, environmental, and social information that contributes to overall sustainable development (Despotovic et al., 2016). Larger firms are more likely to make environmental disclosures (Giannarakis et al., 2020). The dissemination of corporate environmental information can positively affect a firm's market performance and attract the attention of stakeholders. The most common and significant determinants influencing this dissemination are board size, company ownership, and the presence of independent directors (Giannarakis et al., 2020). Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosures relate to a firm's value and project a positive interrelation between data disclosure and the financial development of a firm. The reporting level can enhance a firm's strengths and reduce its weaknesses when the firm's efforts in sustainable development and social investment are stated, even if ESG disclosures are made through the Internet of Things and social sites (Khalid et al., 2022).

Some companies have started deploying technological tools, including digitalization, to address social and environmental goals (core to their identities and within their scope of influence) and accomplish defined sustainability purposes (George & Schillebeeckx, 2021). The digital tools businesses use to address sustainability challenges include instrumentation, tokenization, gamification, reintermediation, contracting and layering, and digitizing institutions (George et al., 2020). Businesses and governments acquire new tools to help with sustainability efforts and purposes through the convergence of digitalization and sustainability, with real opportunities to positively impact the planet (George & Schillebeeckx, 2021).

Knowledge assets are essential resources for firms in determining success and customer satisfaction (Wang et al., 2022). Green knowledge allows for the accomplishment of sustainable goals, whereas green innovation encompasses management and technological innovation (Khan, Mehmood et al., 2024). Green knowledge management enables organizations to successfully identify their human capital potential for implementing green initiatives, thereby enhancing green performance (Khan, Mehmood et al., 2024; Sahoo et al., 2023).

Thus, from a firm's perspective, the sustainability dilemma refers to the challenge of balancing the short-term financial interests of shareholders with the long-term environmental and social impacts of the firm's operations (Carmine & De Marchi, 2023), ensuring that consumers value it. Firms are under pressure from shareholders to maximize profits and generate high returns on investment (Mazzi, 2020). This often leads to decisions that prioritize short-term financial gains over long-term environmental and social sustainability. However, firms increasingly face pressure to operate sustainably from consumers, employees, and other stakeholders (Goh & Balaji, 2016). Consumers are more likely to support companies with a strong record of environmental and social responsibility. Employees are more likely to be attracted to and engaged in work that has a positive impact on the world. Investors are increasingly considering ESG factors when making investment decisions.

The overall sustainability dilemma is a complex issue faced by consumers and firms. Nonetheless, the issues of resource overconsumption and waste production in certain sectors are commonly raised, such as in the tourism and hospitality industry (Agyeiwaah, 2020; Saito, 2013). In this industry, hotels have been the focus of several studies ranging from sustainable practices adopted in the three domains of sustainability (Guzmán-Pérez et al., 2023; Khatter et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2019) to the advantages acquired (Chandran & Bhattacharya, 2019) and the barriers faced (Khatter et al., 2021). Less expressive but also acknowledged are the effects of these practices on consumer behavior (Wang et al., 2019) such as their willingness to value or pay for these types of hotels (Han & Kim, 2010; Kim & Han, 2010), or even perceived greenwashing (Guzmán-Pérez et al., 2023; Majeed & Kim, 2023). Thus, from a micro perspective (Milfont & Markowitz, 2016), individual behavior toward specific sustainable offers can help not only incentivize the adoption of sustainable practices but also provide a deeper understanding of the attitude–behavior gap.

As documented by Arun et al. (2021), various studies have employed the TPB model to explain the consumption intentions of green hotel offerings (Chi et al., 2022; Teng et al., 2015; Verma et al., 2019). These authors also found studies that explored an extended version of this model to examine tourists’ prior experiences with a particular hotel (Nimri et al., 2020), perceived moral obligation (Chen & Tung, 2014), conscientious green behavior, and consumer satisfaction (Han & Kim, 2010; Kim & Han, 2010). The TPB is a widely used model in social psychology, particularly in the context of pro-environmental behavior (Phillips, 2019). This is because the shift toward more sustainable consumption patterns is influenced by a mix of personal attitudes that foster specific intention behavior (Quoquab & Mohammad, 2017). The TPB posits that behavioral intention is the best predictor of behavior and that this intention is influenced by three main factors: attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (Bosnjak et al., 2020). Attitude refers to an individual's positive or negative evaluation of the behavior. For instance, positive attitudes toward sustainable consumption increase the likelihood of engaging in such practices. Subjective norms consider an individual's perception of social pressure or expectations to perform or avoid behaviors. If individuals believe that their peers, family, and social groups approve of their behavior, they are more likely to follow suit. Perceived behavioral control reflects an individual's belief in their ability to perform a behavior. If someone feels confident in their ability to perform a specific behavior, they are more likely to intend to do so. Bosnjak et al. (2020) posited that attitudes toward the action and perceived behavioral control are often responsible for any variation in intention. The second hypothesis considers this rationale.

H2

Environmental concern is positively related to attitudes toward green hotels.

Various other theories have been applied to understand consumers’ choice of green hotels. For example, Han and Kim (2010) extended the TPB to explain consumers’ use of green hotels and environmental concern. Their model also suggests that environmental concern can influence perceived behavioral control by making consumers more aware of green hotel options and confident in their ability to choose and stay at these hotels (Tan, 2023), which reflects consumers’ actual knowledge about green offers (Viglia & Acuti, 2023). Ahmed et al. (2022) extended the TPB framework by incorporating environmental consciousness as a critical antecedent of consumer behavior. Their study found that environmental concern enhances individuals’ confidence in their ability to engage in ecofriendly behaviors. This increased perceived control stems from a deeper awareness and understanding of environmental issues, which motivates individuals to take actions that mitigate environmental impacts (Ahmed et al., 2022). Thus, when individuals believe they have the necessary resources, knowledge, and opportunities to engage in green behavior, they are more likely to do so. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H3

Environmental concern is positively related to perceived behavioral control.

Based on their review, Arun et al. (2021) concluded that consumers are increasingly willing to adopt green hotel products and services, denoting that numerous factors can influence their adoption decisions, including price, perceived benefits, and subjective norms. Yeh et al. (2021) found that perceived behavioral control has a stronger impact than attitude on the intention to stay at a green hotel. Kim and Han (2010) modified the TPB to include environmental concern and found that guests’ awareness of the benefits is crucial for forming the intention to pay green hotel prices. Kang et al. (2012) and Casado-Díaz et al. (2020) found a positive relationship between environmental concern and willingness to pay for green initiatives, with hotel guests looking for luxury and mid-priced accommodation being more willing to pay premiums. Riva et al. (2022) observed a similar effect in restaurants. Kang and Nicholls (2021) found that the relationship between environmental concern and willingness to pay is stronger for consumers who are less price-sensitive and have higher incomes. This suggests that environmental concern is a more important factor for consumers who can afford to prioritize the environment in their travel decisions. Therefore, we propose that the antecedent components of the extended TPB model, especially environmental concern, affect the intention to pay green hotel prices.

H4

Attitudes toward green hotels are positively related to the intention to pay green hotel prices.

H5

Subjective norms are positively related to the intention to pay green hotel prices.

H6

Perceived behavioral control is positively related to the intention to pay green hotel prices.

MethodsTwo studies were designed to shed light on the attitude–behavior gap at the macro and micro levels. Study 1 examined data from the Eurobarometer 92.4 (ZA7602) database, whereas Study 2 employed data gathered through an online survey in one of the countries included in Study 1 (Portugal), focusing on green hotels. The online questionnaire was structured into five sections corresponding to the TPB model adapted by Kim and Han (2010): (i) environmental attitudes; (ii) overall environmental behavior; (iii) environmental behavior during travel; (iv) perspectives on environmental practices in hotels, including willingness to pay; and (v) socioeconomic, demographic, and traveling profiles. Both studies were quantitative and survey-based, and attempted to determine the correlations between the independent and dependent variables in the context of the direct and indirect effects using structural equation modeling (SEM). SEM is particularly suitable for our study since it can model the complex relationships between multiple independent and dependent variables simultaneously (Paul et al., 2016). Given the multifaceted nature of SCB and attitude–behavior gap, SEM can also capture the direct and indirect effects of various factors such as environmental concern, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Finally, SEM provides comprehensive model fit indices (e.g., comparative fit index, Tucker–Lewis index, and root mean square error of approximation) that allow us to evaluate how well our hypothesized model fits the observed data. These indices offer a rigorous assessment of model validity and help us ensure that our theoretical propositions are supported by empirical evidence.

To assess respondents’ environmental awareness, attitudes, and actions, we developed the following constructs: environmental concern, environmental attitudes, perceived consumer effectiveness, environmental actions, problem tackling, attitude–behavior gap, behavioral beliefs, normative beliefs, control beliefs, attitudes toward the behavior, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, environmentally conscious behaviors, and intention to pay green hotel prices. Each construct was meticulously defined to encapsulate the specific dimensions of environmental psychology and behavior, with a number of the items reflecting the extent of the measurement in Studies 1 and 2. Table 1 summarizes the key constructs, their definitions, and the corresponding items measured in our studies.

Constructs used in the models.

| Construct | Definition | No. of items |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental concern (Studies 1 and 2) | Respondents’ awareness of the environmental degradation caused by their daily consumption and production behaviors. | 4 (Study 1)3 (Study 2) |

| Environmental attitudes (Study 1) Perceived consumer effectiveness (Study 2) | Respondents’ awareness of environmental degradation and responsibility for adopting environmentally friendly consumption behaviors. | 7 (Study 1) 4 (Study 2) |

| Environmental actions (Study 1) | Respondents’ practical, feasible, and consciously implemented environmental actions (e.g. traveling less) to tackle the environmental problem. | 14 |

| Problem tackling (Study 1) | Respondents’ environmental actions to practice ecofriendly consumption behaviors and other sustainability-oriented actions to improve the environment. | 3 |

| Attitude–behavior gap (Study 1) | The difference between respondents’ perception of the relevance of the behavior needed to tackle major environmental problems and their willingness to sacrifice resources, comfort, and convenience to display consistent and coherent behavior. | |

| Behavioral beliefs (Study 2) | Respondents’ beliefs about the positive and negative consequences of environmentally sustainable friendly consumption behaviors. | 6 |

| Normative beliefs (Study 2) | Respondents’ perception of how a behavior influences significant others (e.g., family members and friends). The concept measures the extent to which individuals think they must comply with what significant others reason what should or should not be performed. | 3 |

| Control beliefs (Study 2) | Respondents’ beliefs about the occurrence of factors that may either facilitate or impede achieving the target behavior. This concept relates to individuals’ belief in their ability to achieve a goal and perform according to their attitudes and beliefs. | 3 |

| Attitudes toward the behavior (Study 2) | Respondents’ positive or negative evaluation of their behavior. | 7 |

| Subjective norms (Study 2) | Respondents’ perception of the social normative pressure from significant others to perform or not the behavior under consideration. | 3 |

| Perceived behavioral control (Study 2) | Respondents’ assessment of the perceived ease of performing a behavior. | 3 |

| Environmentally conscious behaviors (Study 2) | Respondents’ degree of empathy and emotional reaction toward the problems to be tackled. | 3 |

| Intention to pay green hotel prices (Study 2) | Respondents’ (stated) willingness to pay for higher environmental quality and a premium for ecofriendly products. | 3 |

The data for Study 1 were taken from the Eurobarometer 92.4 (ZA7602) database (additional information can be retrieved from https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2257). The Eurobarometer survey aims to identify EU citizens’ attitudes toward environmental protection by country. We analyzed the responses of 27,498 EU citizens. Their mean age was 51.8 years; 48.1 % were aged 55 years or more, 23.6 % were aged 40–50, and 19.7 % were aged 25–39. More than half (54.2 %) of the respondents were female and the remainder (45.8 %) were male. In total, 13.1 % had a level of education that corresponded to completed secondary school, followed by those with a bachelor's degree (43.4 %) and those with a university degree (35 %). Around 6.1 % belonged to the category “Still studying,” followed by a negligible number of respondents with “No full-time education.”

Around 32.8 % of the respondents lived in rural areas; 38.4 % lived in small or medium-sized towns, whereas 28.6 % lived in large towns. Business proprietors/owners accounted for 6.5 % of the sample, while 8.8 % were classified as directors and 9.7 % described themselves as skilled manual workers. Altogether, 27.9 % of the respondents were married and living without children and 7.8 % were single respondents living with a partner (without children), while 5.7 % were divorced or separated and 8.5 % were widowers (both with children). Approximately two-thirds of the sample reported difficulties in paying their bills most of the time, 24.5 % experienced difficulties from time to time, and 7.8 % almost never.

The variable Environmental Concern was defined as the total number of environmental issues considered as important. The list of issues included aspects such as “direct impact on daily life,” “consumption habits adversely affecting the environment,” and “worry about the impact of plastics on the environment.” This variable included 11 items. Each item was defined as a dichotomous variable, taking the value of 1 if the respondent considered the topic to be important and 0 otherwise.

The variable Environmental Attitudes was defined as the average extent to which the respondents agreed or disagreed with seven statements based on a four-point Likert scale. One such statement was “Your consumptions habits adversely affect the environment.” The Likert scale was inverted, with 4 being the highest score instead of 1.

The variable Environmental Actions was defined as the total number of environmental actions pursued by respondents, such as traveling less, reducing overpackaging, avoiding single-use plastics, and separating waste. This variable included 14 items. Each item was defined as a dichotomous variable, taking the value of 1 if the respondent considered the topic to be important and 0 otherwise.

The variable Problem Tackling was defined as the total number of environmental issues that must be dealt with as a priority. This variable included three items. Each item was defined as a dichotomous variable, taking the value of 1 if the individual considered the measure to be important and 0 otherwise.

Main findings of study 1To validate H1, we examined the influence of environmental concern and environmental attitudes on problem tackling and environmental actions from the macro perspective. On average, the respondents reported 4.2 environmental actions to be prioritized. The mean Environmental Concern was 3.5 and the mean Environmental Attitudes was 3.2. Finally, the respondents indicated that on average, 2.6 problems must be tackled as a priority (see Table 2).

The results indicated that approximately three of every four respondents considered current environmental issues to have a direct effect on their daily life and health status. Many of the respondents considered protecting the environment as a key priority and a particularly important element in their lives. Moreover, most thought that fostering tangible improvements in the environment enhances their lives and brings about more opportunities. The respondents also expressed the belief that tackling environmental problems implies changes in the way they consume as well as in the way we produce and trade. They showed higher expectations from the government and from themselves. Fig. 2 shows the correlations among these four variables.

The analyzed model had an R2 value of 0.29. However, the data indicated a moderate correlation between Environmental Attitudes and Environmental Concern (ρ=0.270; sig=0.001; see Table 3). A higher Environmental Concern score and an improved environmental profile led to higher scores in terms of the respondents’ support for action plans and decision-making processes in line with the environmental agenda. The impact of the respondents’ Environmental Concern was higher for Problem Tackling.

SEM coefficients.

| Std. Coefficient | Std. Error | z | P > z | [95 % conf. | interval] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Actions | ||||||

| Environmental Concern | .2792709 | .0054996 | 50.78 | 0.000 | .2684919 | .2900498 |

| Environmental Attitudes | .1870166 | .0056717 | 32.97 | 0.000 | .1759002 | .1981329 |

| _cons | −0.5516214 | .0333429 | −16.54 | 0.000 | −0.6169723 | −0.4862704 |

| Problem Tackling | ||||||

| Environmental Concern | .4493193 | .0047033 | 95.53 | 0.000 | .4401009 | .4585376 |

| Environmental Attitudes | .109984 | .0054187 | 20.30 | 0.000 | .0993635 | .1206045 |

| _cons | 1.251847 | .0351432 | 35.62 | 0.000 | 1.182968 | 1.320727 |

| var(e.Sqa6) 0.8588636 0.0037546 | .8588636 | .0037545 | .8515365 | .8662539 | ||

| var(e.Sumqa10ETackling) | .7593625 | .0042169 | .7511424 | .7676725 | ||

| LR test of model vs. Saturated | chi2(1)=1102.94 | Prob > chi2=0.0000 | ||||

Table 4 shows the model fit statistics. The model was deemed acceptable as both the comparative fit index and the Tucker–Lewis index were above 0.09. The root mean square error of approximation was <0.05; the upper confidence interval of the root mean square did not exceed 0.10, and the other indices indicated a good fit.

The country-level analysis showed relatively high variability in the four variables included in the model. The less stable coefficient was linked to the impact of Environmental Concern on Environmental Actions.

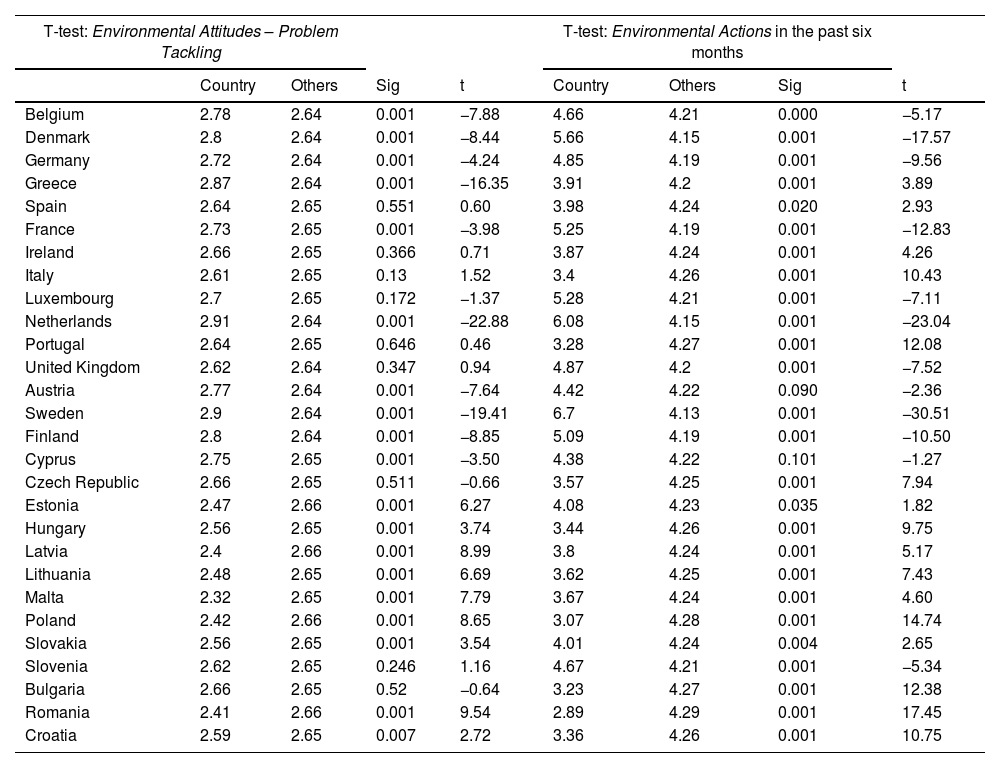

Table 5 shows the significant differences between the countries’ values and the mean score, which compelled us to analyze the origins of these differences. Table 6 reports the mean scores of Environmental Attitudes and Environmental Actions by country. The number of environmentally friendly actions pursued in the past six months was defined as a proxy of the construct “Behavior,” whereas the degree of importance attached to the ways listed in the survey as effective for tackling environmental problems was defined as a proxy of the construct “Attitude.” To establish the influence of national factors on SCB, a proxy variable of gross domestic product (GDP) was used to measure the degree of the development of a country, alongside the indicators of sustainable behavior (environmental attitudes and environmental actions).

Variability by country: Environmental Attitudes and Environmental Actions.

| T-test: Environmental Attitudes – Problem Tackling | T-test: Environmental Actions in the past six months | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Others | Sig | t | Country | Others | Sig | t | |

| Belgium | 2.78 | 2.64 | 0.001 | −7.88 | 4.66 | 4.21 | 0.000 | −5.17 |

| Denmark | 2.8 | 2.64 | 0.001 | −8.44 | 5.66 | 4.15 | 0.001 | −17.57 |

| Germany | 2.72 | 2.64 | 0.001 | −4.24 | 4.85 | 4.19 | 0.001 | −9.56 |

| Greece | 2.87 | 2.64 | 0.001 | −16.35 | 3.91 | 4.2 | 0.001 | 3.89 |

| Spain | 2.64 | 2.65 | 0.551 | 0.60 | 3.98 | 4.24 | 0.020 | 2.93 |

| France | 2.73 | 2.65 | 0.001 | −3.98 | 5.25 | 4.19 | 0.001 | −12.83 |

| Ireland | 2.66 | 2.65 | 0.366 | 0.71 | 3.87 | 4.24 | 0.001 | 4.26 |

| Italy | 2.61 | 2.65 | 0.13 | 1.52 | 3.4 | 4.26 | 0.001 | 10.43 |

| Luxembourg | 2.7 | 2.65 | 0.172 | −1.37 | 5.28 | 4.21 | 0.001 | −7.11 |

| Netherlands | 2.91 | 2.64 | 0.001 | −22.88 | 6.08 | 4.15 | 0.001 | −23.04 |

| Portugal | 2.64 | 2.65 | 0.646 | 0.46 | 3.28 | 4.27 | 0.001 | 12.08 |

| United Kingdom | 2.62 | 2.64 | 0.347 | 0.94 | 4.87 | 4.2 | 0.001 | −7.52 |

| Austria | 2.77 | 2.64 | 0.001 | −7.64 | 4.42 | 4.22 | 0.090 | −2.36 |

| Sweden | 2.9 | 2.64 | 0.001 | −19.41 | 6.7 | 4.13 | 0.001 | −30.51 |

| Finland | 2.8 | 2.64 | 0.001 | −8.85 | 5.09 | 4.19 | 0.001 | −10.50 |

| Cyprus | 2.75 | 2.65 | 0.001 | −3.50 | 4.38 | 4.22 | 0.101 | −1.27 |

| Czech Republic | 2.66 | 2.65 | 0.511 | −0.66 | 3.57 | 4.25 | 0.001 | 7.94 |

| Estonia | 2.47 | 2.66 | 0.001 | 6.27 | 4.08 | 4.23 | 0.035 | 1.82 |

| Hungary | 2.56 | 2.65 | 0.001 | 3.74 | 3.44 | 4.26 | 0.001 | 9.75 |

| Latvia | 2.4 | 2.66 | 0.001 | 8.99 | 3.8 | 4.24 | 0.001 | 5.17 |

| Lithuania | 2.48 | 2.65 | 0.001 | 6.69 | 3.62 | 4.25 | 0.001 | 7.43 |

| Malta | 2.32 | 2.65 | 0.001 | 7.79 | 3.67 | 4.24 | 0.001 | 4.60 |

| Poland | 2.42 | 2.66 | 0.001 | 8.65 | 3.07 | 4.28 | 0.001 | 14.74 |

| Slovakia | 2.56 | 2.65 | 0.001 | 3.54 | 4.01 | 4.24 | 0.004 | 2.65 |

| Slovenia | 2.62 | 2.65 | 0.246 | 1.16 | 4.67 | 4.21 | 0.001 | −5.34 |

| Bulgaria | 2.66 | 2.65 | 0.52 | −0.64 | 3.23 | 4.27 | 0.001 | 12.38 |

| Romania | 2.41 | 2.66 | 0.001 | 9.54 | 2.89 | 4.29 | 0.001 | 17.45 |

| Croatia | 2.59 | 2.65 | 0.007 | 2.72 | 3.36 | 4.26 | 0.001 | 10.75 |

Variability by country: Differences in Environmental Attitudes and Environmental Actions.

| Country | Environmental Attitudes | Environmental Actions | Ci/meanC | Difference between Environmental Attitudes and Environmental Actions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A_Attitude | GDP pc | A_Action | R_Attitude | R_GDP | R-Action | D_At-Ac | |

| Belgium | 2.78 | 35,950 | 4.67 | 1.051 | 1.268 | 1.100 | −0.049 |

| Denmark | 2.80 | 50,010 | 5.68 | 1.059 | 1.763 | 1.338 | −0.279 |

| Germany | 2.72 | 35,480 | 4.89 | 1.028 | 1.251 | 1.152 | −0.123 |

| Greece | 2.87 | 17,610 | 3.90 | 1.085 | 0.621 | 0.918 | 0.167 |

| Spain | 2.64 | 23,450 | 3.98 | 0.998 | 0.827 | 0.937 | 0.061 |

| France | 2.73 | 32,530 | 5.24 | 1.032 | 1.147 | 1.234 | −0.202 |

| Ireland | 2.66 | 70,530 | 3.85 | 1.006 | 2.487 | 0.907 | 0.099 |

| Italy | 2.61 | 26,780 | 3.38 | 0.987 | 0.944 | 0.796 | 0.191 |

| Luxembourg | 2.70 | 84,490 | 5.21 | 1.021 | 2.979 | 1.227 | −0.206 |

| Netherlands | 2.91 | 41,860 | 6.08 | 1.100 | 1.476 | 1.432 | −0.332 |

| Portugal | 2.64 | 18,060 | 3.26 | 0.998 | 0.637 | 0.768 | 0.230 |

| United Kingdom | 2.62 | 32,910 | 4.85 | 0.991 | 1.160 | 1.142 | −0.152 |

| Austria | 2.77 | 36,950 | 4.42 | 1.047 | 1.303 | 1.041 | 0.006 |

| Sweden | 2.90 | 44,950 | 6.70 | 1.097 | 1.585 | 1.578 | −0.481 |

| Finland | 2.80 | 37,250 | 5.07 | 1.059 | 1.313 | 1.194 | −0.135 |

| Cyprus | 2.75 | 25,480 | 4.38 | 1.040 | 0.898 | 1.032 | 0.008 |

| Czech Rep. | 2.66 | 18,020 | 3.56 | 1.006 | 0.635 | 0.838 | 0.167 |

| Estonia | 2.47 | 16,490 | 4.08 | 0.934 | 0.581 | 0.961 | −0.027 |

| Hungary | 2.56 | 13,690 | 3.43 | 0.968 | 0.483 | 0.808 | 0.160 |

| Latvia | 2.40 | 12,970 | 3.81 | 0.907 | 0.457 | 0.897 | 0.010 |

| Lithuania | 2.48 | 14,820 | 3.60 | 0.938 | 0.523 | 0.848 | 0.090 |

| Malta | 2.32 | 22,760 | 3.67 | 0.877 | 0.803 | 0.864 | 0.013 |

| Poland | 2.42 | 13,760 | 3.03 | 0.915 | 0.485 | 0.714 | 0.201 |

| Slovakia | 2.56 | 15,920 | 4.02 | 0.968 | 0.561 | 0.947 | 0.021 |

| Slovenia | 2.62 | 21,310 | 4.67 | 0.991 | 0.751 | 1.100 | −0.109 |

| Bulgaria | 2.66 | 6950 | 3.23 | 1.006 | 0.245 | 0.761 | 0.245 |

| Romania | 2.41 | 9610 | 2.88 | 0.911 | 0.339 | 0.678 | 0.233 |

| Croatia | 2.59 | 13,500 | 3.35 | 0.979 | 0.476 | 0.789 | 0.190 |

For comparison purposes, the scores for both Environmental Attitudes and Environmental Actions were divided by the average score for each variable. Then, the difference between the standardized values for each country was computed to understand the attitude–behavior gap. Again, a clear relationship was found between the degree of development, proxied by GDP per capita, and the attitude–behavior gap. The average difference for developed EU countries was −0.1232, which indicates a greater degree of compliance in terms of Environmental Actions than the average “standardized” score for Environmental Attitudes. The opposite result was found for the group of less-developed EU countries, with an average difference of 0.1067. The t-test results were as follows: x̄=0.1067/−0.1232; t = 4.025; sig<0.001. In general, most developed countries were characterized by higher levels of practical involvement and engagement (actual behaviors) than the corresponding figures for the transformed variable of Environmental Attitudes. Being a developed country added 0.230 to the value of the gap based on a simple ordinary least squares regression modeling the impact of the degree of development on the attitude–behavior gap.

Overall, we failed to find support for H1 in Study 1. The differences among the variables in the group comprising the most developed EU countries were minimal. However, the higher GDP per capita, the higher the mean score of Problem Tackling. The Pearson's correlation between the mean score of the respondents’ opinions on the degree of relevance of the different items and GDP per capita was moderate (r = 0.491), but statistically significant. In all likelihood, the respondents understood that a higher living standard is regarded as a driving factor that positively impacts both the willingness to adopt more sustainable behaviors and the volume of resources that can be afforded to sustain a sophisticated attitude and to finance daily actions toward sustainability and sustainable consumption. A similar pattern was identified for the differences between the mean score of Environmental Actions and degree of importance attached to the ways of tackling environmental problems (Problem Tackling). For the differences between Environmental Attitudes and Environmental Actions, the negative values suggest that the score of the latter was higher than the score of the former, which may indicate a gap between what is believed or felt and what is actually done. The positive values seen in countries such as Greece and Portugal suggest that attitudes exceeded actions.

Study 2OverviewConsidering the finding in Study 1 that some countries have a lower understanding of green attitudes than their practices, one country (Portugal) from this group of countries was chosen to analyze which factors may contribute to the attitude–behavior gap in the hotel industry. In Study 2, we examined the attitude–behavior gap in green hotels by adapting the model presented by Kim and Han (2010). We targeted the Portuguese market owing to its historical tradition in tourism and hospitality and its latest developments in the field.

We collected data from the respondents of an online survey conducted from April to June 2023. As Viglia and Acuti (2023) emphasized, researchers must measure actual consumer behavior rather than mere intention because consumers often express positive intentions toward sustainable behavior but these intentions do not always translate into actual behavior. Thus, the survey targeted tourists who had chosen green hotels on their last trip in 2022. This study adhered to all standard reporting guidelines, with all procedures conducted following ethical standards and with the approval of the ethics review board.

Of the 357 respondents, 47.74 % were men. The highest percentage of the respondents was in the 21–40 year group (72.9 %). Regarding education, 62.54 % of the respondents had a bachelor's degree and 22.4 % had a master's degree. Concerning occupation, 19.81 % were self-employed and 54.22 % worked for someone else. Finally, regarding income level, 52.2 % of the respondents declared that their current situation was balanced and that they were self-sufficient. Altogether, 20.33 % claimed to live very comfortably with their current income level and 59 % admitted to living comfortably with their present income. Regarding respondents’ travel experiences, 46.2 % of the respondents usually traveled twice a year.

The survey design followed the scales developed by Kim and Han (2010) with minor adaptations for the hotel industry. Study 2 included the following three variables on beliefs. First, a six-item instrument was used to gauge behavioral beliefs such as the belief in increased social responsibility by choosing to stay at a green hotel for future travel to the same destination. Responses were rated on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7). Similarly, the significance of the outcomes was measured by rating statements such as the importance of being socially responsible from very unimportant (1) to very important (7).

Second, for normative beliefs, a three-item scale with options ranging from very false (1) to very true (7) was used to assess perceptions of family or relatives’ expectations of hotel stays during travel. This also extended the motivation to comply by asking the respondents to rate the likelihood of adhering to family or relatives’ opinions from extremely unlikely (1) to extremely likely (7). Third, control beliefs were evaluated using a three-item scale to determine the extent of the respondents’ agreement with statements on the factors influencing hotel choice such as cost considerations. The seven-point Likert scale ranged from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7). All the remaining questions for measuring the other dimensions (see Table 7) used seven-point Likert scales ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7).

Reliability and validity of the measurement model.

| Dimensions and constructs | Mean | Loading | CA | rho_a | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral beliefs | 0.993 | 0.993 | 0.994 | 0.957 | ||

| BB1. Help save the environment | 4.232 | 0.977 | ||||

| BB2. Be more socially responsible | 4.342 | 0.962 | ||||

| BB3. Stay in a clean and comfortable environment | 4.073 | 0.968 | ||||

| BB4. Perform environmentally friendly practices | 4.364 | 0.955 | ||||

| BB5. Enjoy environmentally friendly products and healthy amenities | 4.235 | 0.977 | ||||

| BB6. Eat fresh and healthy foods | 4.095 | 0.964 | ||||

| Normative beliefs | 0.989 | 0.989 | 0.991 | 0.938 | ||

| NB1. My family thinks I should be willing to pay conventional hotel prices for a green hotel | 3.204 | 0.980 | ||||

| NB2. My friends think I should be willing to pay conventional hotel prices for an environmentally friendly hotel | 3.342 | 0.987 | ||||

| NB3. My colleagues (or co-workers) think I should be willing to pay conventional hotel prices for a hotel that engages in green practices | 3.305 | 0.977 | ||||

| Control beliefs | 0.986 | 0.987 | 0.991 | 0.973 | ||

| CB1. Location of a green hotel needs to be convenient | 4.084 | 0.952 | ||||

| CB2. Conducting green practices while staying at a hotel requires time and effort | 3.448 | 0.950 | ||||

| CB3. My company/school/others that pay(s) for travel expenses encourage(s) me to stay at a certain hotel | 3.224 | 0.977 | ||||

| Perceived customer effectiveness | 0.965 | 0.965 | 0.977 | 0.935 | ||

| PCE1. It is worthless for the individual consumer to do anything about pollution | 4.277 | 0.943 | ||||

| PCE2. When I buy products, I try to consider how my use of them will affect the environment and other consumers | 4.745 | 0.941 | ||||

| PCE3. Since one person cannot have any effect upon pollution and natural resource problems, it does not make any difference what I do | 4.356 | 0.968 | ||||

| PCE4. Each consumer's behavior can have a positive effect on society if they purchase products sold by socially responsible companies | 4.683 | 0.956 | ||||

| Environmental concern | 0.966 | 0.968 | 0.975 | 0.906 | ||

| EC1. The balance of nature is delicate and easily upset | 4.745 | 0.962 | ||||

| EC2. Humanity is severely abusing the environment | 4.356 | 0.953 | ||||

| EC3. The earth is like a spaceship with only limited room and resources | 4.683 | 0.957 | ||||

| Attitudes toward the behavior | 0.986 | 0.986 | 0.991 | 0.973 | ||

| AB1. For me, paying similar for a green hotel is extremely bad/extremely good | 4.389 | 0.965 | ||||

| AB2. For me, paying similar for a green hotel is extremely undesirable/extremely desirable | 4.277 | 0.988 | ||||

| AB3. For me, paying similar for a green hotel is extremely unpleasant/extremely pleasant | 4.246 | 0.984 | ||||

| AB4. For me, paying similar for a green hotel is extremely foolish/extremely wise | 4.283 | 0.983 | ||||

| AB5. For me, paying similar for a green hotel is extremely unfavorable/extremely favorable | 4.261 | 0.985 | ||||

| AB6. For me, paying similar for a green hotel is extremely unenjoyable/extremely enjoyable | 4.210 | 0.975 | ||||

| AB7. For me, paying similar for a green hotel is extremely negative/extremely positive | 4.375 | 0.968 | ||||

| Subjective norms | 0.986 | 0.986 | 0.991 | 0.973 | ||

| SN1. Most people who are important to me think I should be willing to pay conventional hotel prices for a green hotel | 3.479 | 0.991 | ||||

| SN2. Most people who are important to me would want me to pay conventional hotel prices for an environmentally friendly hotel | 3.487 | 0.990 | ||||

| SN3. People whose opinions I value would prefer that I pay conventional hotel prices for a hotel that engages in green practices | 3.591 | 0.978 | ||||

| Perceived behavioral control | 0.971 | 0.971 | 0.981 | 0.945 | ||

| PBC1. Whether I pay conventional hotel prices for a green hotel is completely up to me | 4.126 | 0.970 | ||||

| PBC2. I am confident that if I want to, I can pay for an environmentally friendly hotel | 4.000 | 0.978 | ||||

| PBC3. I have the resources, time, and opportunity to pay conventional hotel prices for a green hotel | 3.779 | 0.968 | ||||

| Environmentally conscious behaviors | 0.961 | 0.962 | 0.975 | 0.928 | ||

| ECB1. I use a recycling center or in some way recycle some of my household trash | 3.910 | 0.982 | ||||

| ECB2. I have tried very hard to reduce the amount of electricity/water I use | 3.936 | 0.988 | ||||

| ECB3. When there is a choice, I always choose that product that contributes the least to pollution | 3.927 | 0.990 | ||||

| Intention to pay green hotel prices | 0.957 | 0.958 | 0.972 | 0.921 | ||

| IP1. I am willing to pay conventional hotel prices for a green hotel | 4.258 | 0.979 | ||||

| IP2. I will try to pay for a hotel that engages in green practices | 4.050 | 0.953 | ||||

| IP3. It is acceptable to pay conventional hotel prices for an environmentally friendly hotel | 4.347 | 0.968 |

Note. CA: Cronbach's alpha; CR: Composite reliability; AVE: average variance extracted.

Finally, demographic questions were adopted from Andriotis and Agiomirgianakis (2010) to profile the tourists, except for those related to income, which used a four-point scale to establish the subjective income scale ranging from 1 (income not enough to survive) to 4 (income is comfortable to live).

To assess the TPB-driven hypothesized model, partial least squares SEM (PLS-SEM) was employed using SmartPLS 4.0. PLS-SEM can handle complex, multivariate relationships and is particularly useful in marketing research, and management studies for modeling relationships and testing hypotheses involving multiple variables (Kurtaliqi et al., 2024).

Main findings of study 2The assessment of the measurement model included an examination of indicator reliability in which the expectations were that the reflective indicator loadings would exceed 0.5; item reliability with Cronbach's alpha values would surpass 0.7; convergent reliability gauged by average variance extracted (AVE) would be greater than 0.5; internal consistency determined by composite reliability (CR) would have a threshold above 0.7, and discriminant validity as per Hair et al. (2019) would be demonstrated. Table 7 displays the indicator loadings, Cronbach's alpha values, composite reliability figures, and AVE for each latent variable.

All the Cronbach's alpha values were above the recommended value, indicating good reliability. The same was observed for the AVE, which was above the expected minimum (0.50) for each construct, thus ensuring convergent validity and the explanatory power of the model (Hair et al., 2019).

After validating the measurement model, a structural model estimation bootstrapping analysis with a subsample of 5000 iterations was conducted to assess the direct effects of all the relationships. The hypothesis testing summary in Table 8 shows that all the relationships found by Kim and Han (2010) were also valid in the case of green hotels. The path coefficients, t-values, and p-values allowed us to find support for all our proposed hypotheses.

Summary of the hypothesis testing.

| Relationship | Path coefficient | t-value | p-value | Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2 | Environmental concern -> Attitudes toward green hotels | 0.948 | 147.836 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3 | Environmentally conscious behaviors -> Intention to pay green hotel prices | 0.143 | 3.101 | 0.002 | Supported |

| H4 | Attitudes toward the behavior -> Intention to pay green hotel prices | 0.430 | 11.366 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H5 | Subjective norms -> Intention to pay green hotel prices | 0.160 | 7.116 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H6 | Perceived behavioral control -> Intention to pay green hotel prices | 0.279 | 4.020 | 0.000 | Supported |

The finding that all the hypotheses were supported by the data implies that environmental concern, environmentally conscious behaviors, attitudes toward the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control are all significant factors influencing an individual's intention to pay green hotel prices.

Discussion, implications, and limitationsDiscussionSeveral models have been proposed to explain SCB (Kostadinova, 2016; Milfont & Markowitz, 2016; Trudel, 2019), which involves making choices that minimize negative environmental impacts and promote long-term sustainability. These models aim to understand the factors that influence consumers’ decisions to adopt sustainable practices in their daily lives. Regardless of the model adopted, evidence shows that in many contexts, an attitude–behavior gap can be found. The attitude–behavior gap in SCB refers to the discrepancy between people's positive environmental attitudes and their actual environmental actions. According to Milfont and Markowitz (2016), unveiling the macro and micro factors that may influence this gap is relevant, especially for firms that face the dilemma of implementing sustainable practices (Couto et al., 2016), because their investments in sustainability may not produce the desired consumer behavior. This study contributes to the theoretical development of SCB by offering a dual-level analysis of the attitude–behavior gap in environmental actions across European countries and within the specific context of the hospitality sector in Portugal.

Our findings underscore the complexity of the relationship between environmental attitudes and behaviors and challenge the notion that higher economic development necessarily translates into more consistent sustainable behaviors. The macro-level analysis, using data from the Eurobarometer survey, reveals that while EU citizens generally express high environmental concern and positive attitudes toward sustainability, these attitudes do not consistently translate into environmental actions. A significant finding is the correlation between a country's GDP and the prevalence of sustainable behaviors. Higher economic development appears to facilitate behaviors that surpass attitudes, suggesting that resources and infrastructure in wealthier countries may support more sustainable actions. However, this correlation also indicates that economic incentives alone are insufficient to bridge the attitude–behavior gap. Psychological and social factors must also be addressed to foster a deeper commitment to sustainable practices.

Contrary to prior assumptions, our results indicated no direct correlation between a country's GDP per capita and the prevalence of positive environmental attitudes or actions. The results of Study 1 demonstrate that environmental concern and attitudes significantly influence consumer behavior regarding environmental actions and problem-solving. Our analysis revealed that most of the respondents acknowledge the direct effects of environmental issues on their daily lives and health. They also consider protecting the environment as a key priority. The results indicated that higher degrees of environmental concern and positive attitudes toward the environment were correlated with increased support for environmental actions and initiatives. Specifically, environmental concern had a more substantial impact on problem-solving priorities. This result highlights the importance of comprehensively addressing such environmental issues. Moreover, the country-level analysis suggested variability in the relationship between attitudes and actions, influenced by factors such as GDP per capita, which affect practical engagement in environmentally friendly behaviors.

The results also revealed differences between the attitude and action scores for each country. For example, Denmark and Sweden showed high attitude scores and even higher action scores, suggesting that a positive attitude translates into a higher likelihood of displaying green behavior. Conversely, countries such as Luxembourg showed high GDP per capita but lower action scores relative to their attitude scores. The results of Study 1 indicated the existence of two markedly different groups in terms of the attitude–behavior gap. The higher the level of economic development proxied by GDP per capita, the higher the scores of Environmental Attitudes and Environmental Actions, but the lower the differences between both these variables. However, the findings of Study 1 suggested that the attitude scores and GDP per capita are not directly correlated. Hence, although economic development may provide the resources necessary for environmental actions, this does not guarantee the adoption of sustainable behaviors. This finding underscores the need for targeted policy interventions that go beyond economic incentives to address the psychological and social factors influencing SCB.

The micro-level analysis focusing on the Portuguese hospitality sector provided further insights into the specific barriers and drivers of sustainable behavior in an industry known for its resource-intensive operations. The application of the TPB demonstrates that factors such as environmental concern, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control significantly influence consumers' intention to pay green hotel prices. However, the persistence of the attitude–behavior gap suggested that positive intentions rarely translate into actual behavior. This finding highlighted the importance of making sustainable choices more convenient and accessible, enhancing consumer confidence in their ability to make environmentally friendly decisions, and leveraging social norms to encourage sustainable behavior.

Both studies highlighted the significant impact of environmental concern on sustainable attitudes and behaviors as well as the persistence of the attitude–behavior gap, indicating that positive environmental attitudes do not always translate into consistent sustainable actions.

Research implicationsEvidence from recent macro-level studies shows that the gap between attitude and behavior toward green products is similar across developed countries (Quoquab & Mohammad, 2020), suggesting that a green attitude and income are the determining factors in diminishing the attitude–behavior gap. However, contrary to prior assumptions (Quoquab & Mohammad, 2020), our results indicate no direct correlation between a country's GDP per capita and the prevalence of positive environmental attitudes or actions. An interesting theoretical contribution of this study is the evidence that both attitude and behavior exhibit a linear growth trend in line with GDP. However, the growth rate of behavior increases significantly when the growth lines intersect, suggesting that at higher GDP levels, actual environmental behavior surpasses attitude. This study further contributes to theoretical development by demonstrating the complex relationship between economic development and the attitude–behavior gap in environmental actions, which highlights the need for nuanced approaches that consider both economic and cultural factors in promoting green behavior.

By demonstrating that higher GDP can enhance actual environmental behaviors more than attitudes, this study underscores the importance of economic development in fostering sustainable action. However, it also reveals that economic incentives alone are insufficient. Furthermore, it emphasizes the need for comprehensive strategies that incorporate psychological and social factors and suggests that policymakers develop programs that enhance perceived behavioral control and leverage social norms to bridge the attitude–behavior gap. These programs include educational campaigns, community initiatives, and incentives to make sustainable choices more accessible and socially desirable.

Furthermore, it provides empirical evidence of the attitude–behavior gap in the context of green hotels, echoing the findings of Gupta and Ogden (2006) and White et al. (2019). Despite high levels of environmental concern and positive attitudes toward green hotels, these attitudes do not always translate into actual behavior or willingness to pay for green hotels. This finding highlights the importance of addressing the barriers that prevent consumers from adopting positive attitudes aligned with the pathways pointed out by Viglia and Acuti (2023). The results indicate that perceived behavioral control and subjective norms significantly impact consumers’ intentions to stay at green hotels, thus emphasizing the importance of these factors in predicting behavior, which aligns with the findings of other studies (Arun et al., 2021; Chen & Tung, 2014; Chi et al., 2022).

These findings have significant implications for policymakers and businesses aiming to promote sustainable practices. At the macro level, policies should not only focus on economic incentives but also incorporate educational campaigns and community initiatives to enhance environmental awareness and perceived behavioral control. At the micro level, industry-specific strategies such as green certification programs and consumer awareness campaigns can help address the unique barriers to sustainable behavior within sectors such as hospitality. By creating an environment where sustainable choices are the norm, these interventions can help reduce the attitude–behavior gap and drive the greater adoption of sustainable practices. For instance, in the hospitality sector, green certification programs for hotels could be paired with consumer awareness campaigns that highlight the benefits of choosing ecofriendly accommodations. Tailoring interventions in specific industries helps address the unique barriers and drivers of sustainable behavior and thereby increases the effectiveness of these initiatives.

The integration of environmental sustainability into broader economic and social policies ensures that sustainable practices are supported by structural conditions. These include investing in green infrastructure, providing financial incentives for sustainable business practices, and enforcing regulations that promote environmental responsibility. Such integrated approaches help create an environment in which sustainable choices are the norm rather than the exception, thus reducing the gap between consumers’ intentions and behaviors. The study's findings underscore the necessity for tailored policy approaches that consider the economic context and environmental attitudes of different populations to enhance the effectiveness of environmental initiatives and actions.

Practical and policy implications and limitationsBased on the results of the present study, hoteliers who aim to align their business practices with SCB and capitalize on the growing market for green hotels should focus on increasing guests’ environmental awareness and concern, as these are critical predictors of positive attitudes toward green hotels. This can be achieved through educational initiatives that highlight the environmental benefits of sustainable practices through digital platforms, in-room literature, and interactive guest experiences. Improving perceived behavioral control is also essential; hoteliers can enhance this perception by making sustainable choices more convenient and accessible, such as providing clear information about green options during the booking process, offering easy-to-use recycling facilities, and ensuring that sustainable amenities are readily available. Leveraging social norms and influences is crucial because subjective norms significantly impact guests’ decisions to stay in green hotels. Hoteliers can foster a sense of community among eco-conscious travelers through online communities, social media groups, and endorsements from influencers or celebrities who are known for their environmental advocacy. Obtaining green certifications and maintaining transparency regarding sustainability efforts enhances credibility and trust among guests and allows for better targeting of green consumers. By enhancing environmental awareness, improving perceived behavioral control, leveraging social norms, and implementing targeted marketing, hoteliers can effectively bridge the attitude–behavior gap and drive greater adoption of green practices among their guests.

Moreover, the overall findings highlight a strong connection between environmental attitudes and willingness to pay more for green services, thus offering significant implications for policy development and advocacy. Policymakers are provided with a compelling basis for creating incentives to encourage hotels to adopt sustainable practices. Additionally, the results can be instrumental for governments and non-governmental organizations in designing public awareness campaigns. These campaigns can educate the public about the environmental impact of hotel choices and thereby steer consumer behavior toward ecofriendly options. This dual approach can help reduce the aforementioned gap. However, its efficiency must be assessed at the macro and micro levels.

One limitation of our work is its geographic scope, as both studies were conducted in Europe. Future research should consider other regions with different cultural, economic, and environmental contexts. Although the results of Studies 1 and 2 confirm the well-known attitude–behavior gap in SCB at the macro and micro levels, they also suggest the need to add new dimensions to the model. Measures of environmental attitudes and behaviors, while comprehensive, may not capture the full spectrum of factors influencing SCB. Therefore, psychological, cultural, and contextual factors beyond those included in the surveys, such as cultural differences between countries, income distribution, and social policies, may play significant roles. Another limitation of the present work is that both studies relied on self-reported data, which can be subject to social desirability bias. Respondents may overstate their positive environmental attitudes and behaviors to align with socially accepted norms, leading to potential discrepancies between reported and actual behaviors. To overcome this limitation, and follow the advice of Viglia and Acuti (2023), future studies should consider measuring the actual behavior using artificial intelligence tools.

ConclusionThe novelty of this study lies in its dual-level analysis of the attitude–behavior gap, encompassing both macro-level (cross-national) and micro-level (sector-specific) investigations across European countries and within the hospitality sector in Portugal. The identification of GDP as a significant variable influencing the gap between attitudes and behaviors adds a new dimension to the literature, challenging the assumption that similar environmental policies yield uniform sustainable behaviors across economic contexts. The findings challenge the assumption that higher economic development necessarily translates into more consistent sustainable behaviors and underscore the need for targeted strategies that address both the economic and the psychological factors influencing SCB. Moreover, our findings support the existence of significant gaps between stated intentions and actual SCB. However, while Quoquab and Mohammad (2017) emphasized the role of policymakers in encouraging green product choices and sustainable practices through policies and awareness campaigns, our study revealed additional nuances. Given that the sample in Study 1 comprised EU countries with ostensibly similar environmental policies, one may expect minimal differences among these countries. Contrary to this expectation, we found notable differences that were strongly correlated with GDP, with behaviors surpassing attitudes in countries with higher GDP.

At the individual level, the TPB suggests that behavior is influenced by three main factors: attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Our theoretical exploration of the attitude–behavior gap in environmental behavior offers several important insights. First, although attitudes are generally positively correlated with environmental behavior, this relationship is not always strong or consistent. Second, subjective norms can either facilitate or hinder environmentally friendly behaviors. Third, perceived behavioral control influences both intentions and behavior, and personal norms are strong predictors of environmentally friendly behavior.

The model proposed by Han and Kim (2010) introduced an additional route linking environmental concern with perceived behavioral control. This connection suggests that heightened environmental concern enhances perceived behavioral control by raising consumer awareness of ecofriendly hotel choices and boosting confidence in selecting and patronizing hotels. The findings also corroborate those of previous studies, especially Han and Kim (2010), who highlighted the significance of environmental concern in shaping attitudes toward green offers and the subsequent intention to pay for such options. This indicates that addressing the attitude–behavior gap requires focused efforts to modify consumer perceptions, provide clear information, and make green choices more intuitive and reflective of consumers’ environmental concern.

CRediT authorship contribution statementMaria Teresa Borges-Tiago: . António Almeida: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis. Flávio Gomes Borges Tiago: . Sónia Margarida Moreira Avelar: .

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (Portugal) through research grants UIDB/00685/2020 of the Centre of Applied Economics Studies of the Atlantic, School of Business and Economics of the University of the Azores and UIDB/04521/2020 of the Advance/CSG, ISEG – Lisbon School of Economics and Management.