In the supply chain, companies are increasingly relying on the combination of internal knowledge creation and external knowledge resources to form a new “open innovation” approach. How to govern inter-organizational relationships (IOR) is a key determinant of knowledge creation, which involves both formal contracts and relationship behaviors. Formal contracts determine the roles and obligations of partners in the exchange, and relationship behavior is generated by mutual benefit from the exchange of various resources. Moreover, when the knowledge creation process requires partners to exchange knowledge, supply chain technologies such as the Internet of Things (IoT) and cloud-computing based advanced communication services are key in promoting the partners’ willingness to communicate. Therefore, this study uses the governance mechanism of the supply chain as a theoretical framework, and proposes an innovative and complete research model to explore the factors that influence open innovation capability in supply chains. PLS is used to analyze 140 samples collected from 600 organizations, the response rate is 23.3%. This study finds that supply chain technology has a stronger effect than both of the IOR issues, contractual governance and relational governance, for the exchange of tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge. The findings improve our understanding on how governance mechanism and technology drive the knowledge creation process towards open innovation success in the context of supply chains.

Globalization and new technologies have led to increased competition, more mobility of skilled workers, as well as shorter product life cycles, smaller profit margins, and higher risks Crupi et al. (2020). As supply chain management (SCM) has increasingly become critical for firms' competitive ability, these transformations with new technologies have made SCM more effective and efficient for their operations (Wu & Chiu, 2018). In supply chains, the concept of innovation has substantially changed the business models of many industries, generating revolutionary improvements in product design and manufacturing processes, as well as product operations and after-sale services (Wu & Chiu, 2018).

Organizational innovation is closely related to knowledge management (Najafi-Tavani, Mousavi, Zaefarian, & Naudé, 2020). Recently, organizational innovation focuses on the acquisition of external knowledge for creating organizational innovation (Lopes, Scavarda, Hofmeister, Thomé, & Vaccaro, 2017; Öberg & Alexander, 2019). Acquiring external knowledge for internal use indicates a kind of innovation that refers to how firms license-in and acquire expertise from outside to promote their performance. This also indicates an important concept of internal knowledge creation for its uniqueness and great value in creating new products or services. Firms rely on internal knowledge creation for a combination with outside expertise or supply chain partners, leading to a new innovation approach called “open innovation,” wherein firms develop new products or services collaboratively through partners’ expertise (Chesbrough, 2003). The concept of open innovation has become increasingly important as many innovative firms change to an open innovation process from an internal R&D process, using a wide range of external knowledge to achieve and sustain innovation (Kim & Chai, 2017; Moretti & Biancardi, 2020).

In open innovation, an organization depends not only on its own knowledge, sources and resources for innovation, but also leverages multiple external sources to drive its innovation, either inside-out and outside-in resource flow (Naqshbandi & Kamel, 2017). The internal learning in a firm and its technological innovation capability is stronger when R&D teams adopt open innovation (Huang, 2011). Lichtenthaler and Lichtenthaler (2009) proposed a capability-based framework for open innovation that includes six ‘knowledge capacities’: inventive, absorptive, transformative, connective, innovative, and desorptive. Hosseini, Kees, Manderscheid, Röglinger, and Rosemann (2017) also proposed an open innovation capability framework (OICF) comprising 23 capability areas based on factors, such as strategic alignment, governance, methods, information technology, people, and culture. Thus, open innovation is a situation of inter-organization collaboration for innovation of products, services, etc. Open innovation capability constitutes capabilities, such as internal learning, technology innovation, governance, etc., that drive open innovation. As this study evaluates open innovation in supply chains, the concept of open innovation capability is proposed as a criterion. Open innovation capability refers to the use of inflows and outflows of knowledge to accelerate internal innovation.

Organizational knowledge creation theories have developed a comprehensive view of knowledge resources that could shed light on organizational innovation. In addition, knowledge creation is also transcending process, expanding new knowledge created through partners and going beyond traditional boundaries for connections to an organization's knowledge system (Jiang & Xu, 2020). Knowledge creation is a synthesizing process that includes explicit and tacit knowledge, demonstrating that it has complementary belongings (Ağan, Acar, & Erdogan, 2018; Öberg & Alexander, 2019). Knowledge creation requires firms to search their external environment, including suppliers, customers, contractors, etc. to find appropriate knowledge to supplement their inner knowledge portfolios (Lichtenthaler & Lichtenthaler, 2009). According to Nonaka (1994), firms create new knowledge by amplifying knowledge that their members hold, which often occurs through a knowledge spiral consisting of four processes of conversion between tacit and explicit knowledge: interactions, socialization, combination, internalization and externalization. Knowledge creation within a supply chain contributes vitally to successfully combining and coordinating various knowledge resources between partners for better competition and it is thus critical for developing new ideas through interactions between tacit and explicit knowledge in an organizational environment (Jiang & Xu, 2020).

The changing business environment has shifting expectations for all supply chain partners, requiring strong management skills and processes to adapt quickly to meet these changing demands. Efficacious knowledge creation results from the synthesis of unique knowledge inputs from partners, as in collaborative partner relationships (Adams & Graham, 2017). Inter-organizational relationships (IOR) are a critical determinant for knowledge creation to occur in supply chains (Saikouk, Fattam, Angappa, & Hamdi, 2021). Much research has been done on IOR to determine collaborative effort or knowledge exchange in terms of relevant relationship theories, such as transaction cost theory (TCT), social exchange theory (SET), social capital theory (SCT), resource dependence theory (SDT) and psychological ownership (Kim & Chai, 2017; Pirkkalainen, Pawlowski, Bick, & Tannhäuser, 2018). There are, however, few studies on the effect of tacit and explicit knowledge creation for source firms in terms of the willingness of partners in supply chains.

As these IOR theories are not defined clearly, some theories may be duplicated each other across their boundaries, such as SET, SCT and SDT (Lopes et al., 2017; Gorovaia & Windsperger, 2018; Kaya & Caner, 2018). This study makes a comprehensive literature review and proposes a new argument for the classification of IOR into contractual and relational governance. Contractual governance shapes partner roles and obligations in supply chain exchanges. A trading contract in supply chains is a formal collaboration of tremendous significance because it imposes legally binding obligations upon its participants. Relational behaviors could also occur as exchanges motivated through perceived mutually benefits to supply chain members in the exchange of various resources (Schoenherr, Narayanan, & Narasimhan, 2015). In contrast, when a firm exchanges resources with partners in a cooperative relationship, this also exposes the firm to the risk of leakage of critical resources, thereby decreasing the willingness to share knowledge (Wang, Wang, & Che, 2019). However, the contractual mechanism could play an important role in the exchange process because it lawfully defines obligations and provides exchange parties with an instrument of appropriate control. Hence, it is crucial to understand the potential impact of the two governance mechanisms, contractual and relational, for effectively managing resource exchange in supply chains in which each mechanism may be closely relevant to knowledge creation process.

Governance mechanisms, both relational and contractual, are schemes of cooperation across organizations in a supply chain management system. New supply chain technologies such as advanced cloud-based communication services have both accelerated communications across organizations and radically changed the SOP of dealing with business. For example, communication time has been reduced due to instant messaging, and ERP systems have shortened business SOPs making them more efficient and customer-driven. Further, business organizations are becoming more adept in developing, adopting, and adapting suitable technologies in their working processes to increase their efficiency and innovation through knowledge exchange (Santoro, Vrontis, Thrassou, & Dezi, 2018). When the knowledge creation process in supply chains needs an important exchange of partners’ knowledge as the input to this process, supply chain technologies, such as IoT and advanced communication technology, are crucial in determining the partners’ willingness to participate in the exchange process for knowledge creation. Thus, this research validates how such new supply chain technologies in collaboration with conventional governance mechanisms can affect knowledge creation, and thus in-turn affect open innovation.

Accordingly, the first research gap shows the different concepts between open innovation and open innovation capability, and indicated how to enhance the open innovation capability in supply chain. Second, we examine how a recursive relationship between tacit and explicit knowledge may foster open innovation capability. Third, though the means by which governance mechanisms, such as contractual and relational governance, influence knowledge creation has been previously investigated; there has been less concern with how IT, such as supply chain technology, together with governance mechanisms together influence knowledge creation. This research gap is important since supply chain technologies, such as IoT and cloud computing, not only enhance the supply chain performance, but also change the infrastructural operation mechanisms. This gap is even more evident when we consider open innovation capability, where IT plays a major role, and its implications with respect to knowledge creation, both tacit and explicit. This study thus proposes a novel research model to examine a source firm's innovation capability through the mediating role of the knowledge creation process from the drivers of IOR with contractual and relational governance and supply chain technology. The knowledge creation process indicates has a dynamic nature in an interactive manner for tacit and explicit knowledge. This study seeks to answer the following two research questions: What is the combined influence of governance mechanisms and supply chain technology on knowledge creation? What is the influence of such combined knowledge creation on open innovation capability?

Literature review and the research modelThe Stimuli-Organism-Response (S-O-R) framework was proposed by Mehrabian and Russell (1974) in the area of environmental psychology. In this framework, environmental stimuli (S) stimulate emotional reaction (O), which in turn affects individuals’ behavioral response (R). Stimulus (S) includes sensory variables and the information load under specific circumstances. Organism conditions indicate an individual's emotional and cognitive states in response to environmental stimulation. Further, responses (R) could either approach or avoid the environment (Xue, Li, & Li, 2022). Chen, King, and Suntikul (2019) pointed out that the S-O-R architecture reflects a reaction process that reveals a continuum of psychological and behavioral reactions. In supply chains, to achieve open innovation capabilities through the knowledge creation process, partners need to serially stimulate their emotional and behavioral reactions, thus leading to their internal or external responses. This study posits that the development of open innovation capabilities in a supply chain is not an immediate process, but also stems from the combined process of psychological feelings and behavioral responses generated after the knowledge creation process. Based on this background discussed, we use stimulus-organism- response (S-O-R) as an overall theoretical basis to define the relationship structure, stimuli for the initial drivers, organisms for the mediators, and responses for the target of our research model. The following discusses the theoretical foundations of this model and the development of hypotheses.

Open innovation capability in supply chainsThere are few firms which gain huge advantages from internal R&D, despite the need for substantial investment to retain their competitiveness in related markets (Rauter, Globocnik, Perl-Vorbach, & Baumgartner, 2019; Moretti & Biancardi, 2020; Giacomarra et al., 2021). Currently, many well-known organizations rely on external resources to go beyond existing business boundaries by developing innovations. Firms work hard to secure knowledge sources through licensing, R&D outsourcing, market channel, brand reputation, or hiring of qualified employees with relevant knowledge (Gast, Gundolf, Harms, & Collado, 2019).

To acquire external knowledge that symbolizes a kind of openness in innovation refers to how firms license-in and otherwise acquire expertise from outside. These interactions have resulted in an innovation trend called “open innovation,” in which companies develop new products, services, or markets collaboratively by using outside knowledge and resources (Rauter et al., 2019; Ardito, Petruzzelli, Dezi, & Castellano, 2020; Park, Shi, Zhou, & Zhou, 2020). Open innovation stresses the relevance of interactive processes, linking inside and outside flows of knowledge by working within alliances of complementary companies (Ardito et al., 2020). Stated differently, open innovation involves using both internal and external knowledge to accelerate inner innovation capability. The firms can and should use external ideas as well as internal ideas, going through internal and external paths to market, as the firms seek to advance their technology. The business model of open innovation process defines requirements for the architecture and systems and utilizes both external and internal ideas to create knowledge value. This indicates the innovation character of a firm participating in the knowledge creation process with its external partners, using business models to mediate innovation.

Therefore, open innovation capability is based on the interactive character of the innovation process, which individuals communicate to each other. The focal firm usually needs to import the critical sources of innovation ideas or new technologies from its suppliers and partners in the supply chain to stimulate its innovation capability (Ardito et al., 2020). This leads to the issue of understanding firm behaviors, which implies building the relationships between the firm and its partners is essential for organization performance. Open innovation capability is the core competition of an organization to increase open innovation in supply chain network (Solaimani & van der Veen, 2021). Procter and Gamble's (P&G's) approach to R&D activities is a case in point. In order to exploit external knowledge sources P&G opened up its innovation strategy by absorbing the ideas of external members, rather than just investing in internal R&D (Han, Thomas, Yang, & Cui, 2019). Another example is the BMW automobile company, which established a co-creation laboratory and enlisted online communities of enthusiastic customers through initiatives such as open innovation contests to share ideas about future concepts for cars and to co-create products and services with the company.

In contrast to open innovation, “closed innovation” is a traditional view that assumes the best route to innovation was to have control over process, to hire the smartest employees, and to protect data internally. Hence, closed innovation is considered to protect a firm from outside competition (Iqbal & Hameed, 2020). However, firms are increasingly firms open to exchanging their knowledge sources and open their innovation processes in bidirectional (outside-in and inside-out) that have been shown to diminish the cost of R&D as compared with internally focused organizations (Giacomarra et al., 2021). According to the previous literature, open innovation capability is a composite of outside-in and inside-out innovation indicators that may be very different from each other and are proposed to measure an organization's open innovation capability in this research.

Knowledge creation processKnowledge creation represents a process of interpersonal interactions, team-based structures, network ties, business intelligence, and challenges across communications at the meso-organizational and inter-organizational level. Following Grant (1996) suggestion of focusing on types of knowledge, the knowledge resources can be simply divided into the two dimensions of explicit knowledge and tacit knowledge. Explicit knowledge refers to concept, experiences and information that could be codified or digitized in documents, reports, books and so forth. Tacit knowledge refers to concepts, as opposed to formal codified, embedded in the human mind through experience and jobs, associated with experience and being related to human asset specificity; it is difficult to capture, codify, write down or verbalize this kind of knowledge.

The Nonaka and Toyama (2003)SECI (socialization, externalization, combination and internalization) processes model of dynamic knowledge creation is about continuous transfer, combination, and conversion of the two types of knowledge outlined above and how knowledge is converted and created as individuals practice, collaborate, and interact in the organizations. Socialization (tacit to tacit) is a process whereby converted tacit knowledge is transmitted through experiences, imitation, and observation. Externalization (tacit to explicit) is a process whereby tacit knowledge is codified into documents, manuals etc. so that it can be shared by others and spread more easily through the organization to become the basis of new knowledge. Combination (explicit to explicit) is a process in which codified knowledge sources (e.g., documents) collected from inside or outside the organization are combined and edited, thereby creating new knowledge. Internalization (explicit to tacit) is a process where explicit knowledge is used, learned, created, and shared throughout an organization; knowledge is converted into tacit knowledge by individuals and the individuals' existing tacit knowledge is modified, becoming the base for new routines. The continuous iterations of the process amplify the knowledge to higher-level knowledge-creating activities; the knowledge creation process interchanges explicit and tacit knowledge from individual to group to organization to community of organizations. These knowledge resources can help firms promote their contingency management abilities to confront the changeable, competitive environment, and provide mutual benefits (Sun, Liu, & Ding, 2020).

Governance mechanisms in supply chainsInter-organizational governance stipulates formal and informal rules of exchange between two or more parties (Vandaele, Rangarajan, Gemmel, & Lievens, 2007). Governance mechanisms used to manage IORs affect not only the performance of focal firms but also that of their customers, suppliers, and business partners. Related studies have distinguished between two types of governance mechanisms: contract governance and relational governance (Griffith & Myers, 2005; Vandaele et al., 2007).

Current research on governance mechanisms starts with a theoretical frame of reference affected by theoretical lenses. In contractual governance, parties write detailed and legally binding agreements (Vandaele et al., 2007) which specify roles and obligations of contracting parties (Lyons & Mehta, 1997). Transaction cost theory is a dominant theoretical frame of reference (Dyer, 1997) that adopts a transaction cost economics (TCE) perspective and tries to explore relationships between transaction characteristics, for example, uncertainty and asset specificity, as well as, contract design (Schepker, Oh, Martynov, & Poppo, 2014). Transactions characterized by lower uncertainty and asset specificity do not need detailed contracts; however, partners may design detailed contracts, with safeguarding clauses for conducting uncertain, asset-specific transactions (Reuer & Ariño, 2007). In addition, agency theory helps delineate circumstances under which the interplay and potential complementarity effects between trust and contractual controls occur. Relational governance appears in socially derived ‘arrangements’ that are more informal than contractual governance (Vandaele et al., 2007). Social exchange theory and social capital theory are conceptual lenses frequently used in the literature. In supply chains, network relationships rely on generalized social exchanges, where obligations to one party could be transferred to another in the network. Therefore, network transactions are governed via indirect reciprocity, where members repay the favor obtained from one member to another member of the network. Relational governance, as well as, coordination in network relationships is significant because it is a challenge to design explicit contracts in networks.

In supply chain management, the governance mechanism refers to facilitation of interactions between the focal firm and its partners to create value and competitive advantages through specific relationships that can continue for a long time, foster information exchange, create new ideas to form their own knowledge, and enhance efficiency in cooperative relationships (Jimenez-Jimenez, Martínez-Costa, & Rodriguez, 2018). The governance mechanism provides safeguards for an organization to manage inter-organizational interactions, avoid exposure to opportunism and protect its investments (Huang & Chiu, 2018). Therefore, a focal firm aligns the governance features of inter-organizational relationships to exchange risks such as patent license, domain know-how, specialized asset investments, and new technology.

Contractual governanceContractual control has progressed from a focus on designing complete contract to recognizing the challenges of constructing reliable contracts for the exchange of resources, information that is difficult to fully describe since it depends on future conditions in an uncertain environment (Um & Kim, 2019). Contractual control emphasizes that the supply chain members need to write out procedures and roles for monitoring, performance obligations, and future outcomes, enabling parties to reduce costs by recognizing contingencies and establishing suitable commitments (Um & Kim, 2019). There are varieties of contractual arrangements, and supply chain contracts can be either complete or incomplete. Complete contracts are formulated by specifying all conceivable scenarios; incomplete contracts are established by parties who recognized that not all factors affecting a contract are foreseeable at the time it is completed (Um & Oh, 2020). With globalization, an organization needs even more information and knowledge from its suppliers, contractors, and customers. Even highly vertically integrated firms devolve decision rights to set incentives and structure the flow of information (Howard, Roehrich, Lewis, & Squire, 2019). Jia, Wang, Xiao, and Guo (2020) pointed that it is difficult for retailers to forecast business marketed demands if they make one-sided decisions according to limited information, and it is also difficult to comprehend the entire supply chain and individual enterprises to achieve the optimal profit at the same time. Howard et al. (2019) stated that applying contractual control can promote long-term relationships and enhance performance. However, firms incur extremely high cost for gathering information, considering all uncertainly risks, and the feasibility of designing complete contracts. Hence, developing an effective contract mechanism to exchange information and promote cooperation among supply chain members may be effective for all parties.

Relational governanceThough the role of contracts is well known to be critical and valuable, a great deal of research had shown that it is insufficient to rely on a formal contract alone (Howard et al., 2019; Um & Oh, 2020). Relational governance includes the enforcement of commitments, obligations, promises, activity expectations, and common goals; this relational governance occurs through trust and social identification (Um & Oh, 2020). It uses shared values, resources, knowledge, social norms, and consistent goals to encourage specific behaviors that limit opportunism (Um & Kim, 2019). In supply chains, building or maintaining long-term exchange relationships may be complicated because it is very difficult for firms to protect themselves from all unanticipated obligations. Consequently, it is necessary to govern closer relationships beyond contractual provisions. Schoenherr et al. (2015) pointed out that trust and commitment in exchange relationships are based on a social element. Empirical studies have demonstrated that relational governance may enhance the performance of inter-organization exchange behaviors and IT outsourcing (Um & Oh, 2020). Inter-organization coordination and exchange behaviors act as social interactions, and there is an operating system as a social network. Compared to contractual governance, relational governance emphasizes mutual benefits and norms, requires supply chain partners to share values, knowledge, beliefs and goals to foster entire supply chain performance, and ensures appropriate activities that can be reinforced and rewarded (Tse, Zhang, Tan, Pawar, & Fernandes, 2018). Relational norms encourage communication between buyer and seller to raise partners’ familiarity, trust, and shared experiences, thereby limiting opportunistic behavior (Najafi-Tavani et al., 2020). Supply chain relationships should be viewed as an investment that may bring potential interest and enhance collaborative performance by increasing partners’ trust, learning, and knowledge sharing (Ramon-Jeronimo, Florez-Lopez, & Ramon-Jeronimo, 2017).

Supply chain technologyContemporary social networks are considered to a part of knowledge-creating society. The development in information and communication technologies (ICT) changes the supply chain partners working style to organization collaboration, thus making notes, rules, and processes easier to write down; it also digitizes documents, shares information, and promotes knowledge exchange. Information technology (IT) is essential to support exchange behaviors and decrease the locational and temporal constraints of organizations, thereby facilitating the emergence of global networks and supporting the sharing of intellectual achievements among members in supply chain (Jimenez-Jimenez et al., 2018). IT enables the redesign of many traditional processes through internal and external integration, such that a protective barrier around an organization's resource is eliminated. With the advent of interaction, organizations use digital technologies to seek an optimal capacity to create and apply new knowledge in order to facilitate organizational innovation (Yeniyurt, Wu, Kim, & Cavusgil, 2019). The knowledge resource flow in supply chain based on the idea that information technology disclosure can be a good alignment and is a great benefit for storing explicit knowledge (Shahzad et al., 2020).

Digital technologies for supply chains include information systems technology, operations management, intelligent automation, and equipment. Sensors collect data within a reconfigurable or additive manufacturing operations system (Schniederjans, Curado, & Khalajhedayati, 2020). The data are then automatically processed via robotics, artificial intelligence, and machine learning techniques, without explicit programming (Schniederjans et al., 2020). Actuators were formerly controlled centrally via a supercomputer, but with new distributed technologies, they directly communicate with each other via sensors, without supercomputers or human intervention (Lyall et al., 2018; Schniederjans et al., 2020). In addition, automated technologies such as drones, autonomous vehicles, and augmented reality have been introduced into supply chains (Bhuiyan, Wu, Wang, Wang, & Hassan, 2017). All the sensors, actuators, and equipment, along with data, are then integrated within a cloud computing server that can process big data with cyber-security. Blockchain in the form of incorruptible ledgers of transactions allow the data in supply chains to be stored securely, processed across organizations, and retrieved transparently (Tapscott & Tapscott, 2016). A comprehensive review of IOS literature found that recent studies have emphasized the relative advantage, compatibility, and security of information flow that are commonly recognized as the most important drivers in exchange behaviors, efficiency improvement, information integration, and information flow among inter-organizations (Wu & Chiu, 2018). In sum, the supply chain technology may contribute to promoting very different, but closely interconnected thoughts and make in-house ideas available to supply chain partners, since successful knowledge creation process requires the integration of both internal and external components and competences.

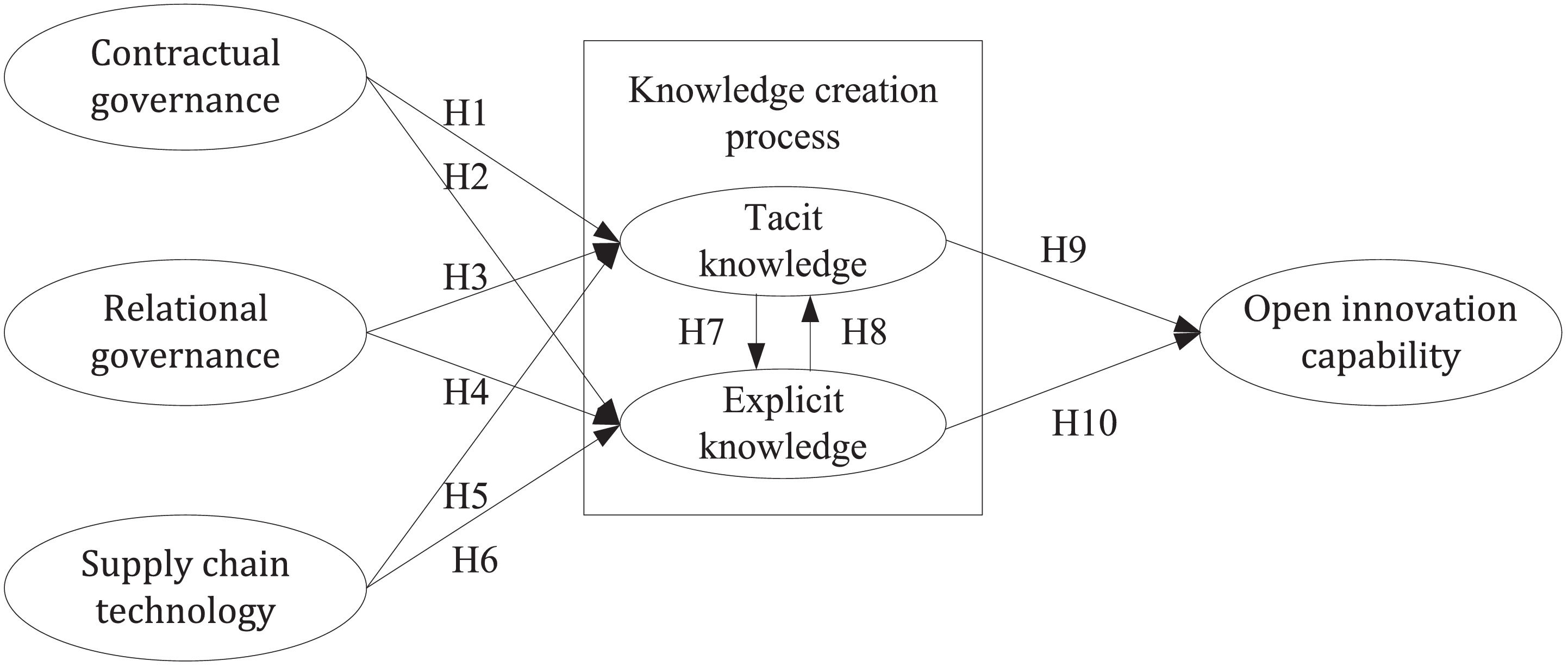

The proposed research model is shown in Figure 1, and definitions for each construct are in Table 1. The validation of this model, along with the investigative constructs and their given associations in our research model, is as follows.

Construct definitions

| Construct | Operational Definitions | Resources |

|---|---|---|

| Contractual governance | Supply chain members define procedures and roles for monitoring, performance obligations, and future outcomes, thus reducing costs by identifying contingencies and setting up suitable commitments across the parties. | Um and Kim (2019) |

| Relational governance | Supply chain members obey the enforcement of commitments, obligations, promises, activity expectations, and common goals via trust and social identification. | Um and Oh (2020) |

| Supply chain technology | Information and communication technology (ICT) changes the supply chain partners working style into organization collaboration, formulating rules and processes that are easier to document, digitizing documents, sharing information, and promoting knowledge exchange. | Jimenez-Jimenez et al., (2018) |

| Tacit knowledge | This kind of knowledge is accumulated in the human mind through experience and jobs associated with experience, and it relates to human asset specificity. | Öberg and Alexander (2019) |

| Explicit knowledge | This kind of knowledge can be codified or digitized in documents, reports, books, etc. | Öberg and Alexander (2019) |

| Open innovation capability | Partners use the inflows and outflows of knowledge to speedup internal innovation. | Behnam, Cagliano, and Grijalvo (2018) |

Knowledge is a powerful resource to solidify competitive advantage and economic growth for supply chain partners. Knowledge creation is defined as the ability to explore new and useful ideas. Firms generate new knowledge in a supply chain via official business activities, meetings, and brainstorming sessions, which bring new ideas and solutions to problems encountered by companies. Business Process Reengineering (BPR), a formal continuous improvement process for quality management, is a knowledge creation process, using firms’ intangible resources efficiently under contracts (Ağan et al., 2018). The effective creation of knowledge is a critical issue for supply chains.

Formal contracts are a key factor for organizations to create knowledge in a supply chain. The success factors in the process of inter-firm knowledge creation are based on making clear roles, statements and responsibilities, together with the exchange of complementary domain knowledge among partners (Chi, Huang, & George, 2020). Gorovaia and Windsperger (2018) investigated the role of contracts in leveraging knowledge-based resources, finding that organizations exploited knowledge-based resources based on both normative rules and the unambiguously specified conditions of the knowledge sharing arrangement. As a result, contracts are platforms for learning processes that utilize complex interactions to explore knowledge for joint value creation. An organization's skill in building contractual governance may directly affect the utility of knowledge resources. Wang, Huang, Davison, and Yang (2018) argued that screening contracts were used to align the incentives for knowledge sharing in a supply chain with private information. The ability to absorb, transfer, combine, utilize, and create knowledge resource was as a potent source of competitive advantage where competitively significant abilities rested on managerial practices, which, in turn, relied on formal contracts (Kaya & Caner, 2018). Wang and Shi (2019) demonstrated that multinational corporations made knowledge contract as a governance mechanism, were ruled by control partners’ behaviors, and gave expatriate managers a view of corporate-level objectives to align their interests. Recently, Jen, Hu, Zheng, and Xiao (2020) showed that organizations could significantly change their work processes and improve the subsequent knowledge integration through formal interactions and interventions to direct their attention on work activities. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed.

H1. Contractual governance positively affects tacit knowledge in a knowledge creation process.

H2. Contractual governance positively affects explicit knowledge in a knowledge creation process.

In organization relationships, trust plays a vital role and is a necessary condition determining organization relationships. Bouncken, Hughes, Ratzmann, Cesinger, and Pesch (2020) pointed out the relationship of trust is less to trigger questioning and scrutiny, validation, but trust can facilitate the transfer of knowledge, in particularly, the transfer of tacit knowledge. A relationship, based on deep trust, can create openness and freedom at the individual and group level that can be manifested in commitment, communication, and ethical behaviors. The kind of relationship plays an essential role in information sharing and knowledge creation and problem-solving, strengthening relationships between supply chain partners.

Öberg and Alexander (2019) proposed that knowledge creation via interactions of supply chain partners may enable more efficient and effective supply chain processes. The created and exploited knowledge resource is considered as a benefit for the pursuit of supply chain relationships themselves. Explicit knowledge may converge when supply chain members understand their partners’ needs and current knowledge warehouses are shared and reused (Maravilhas & Martins, 2019). Common activities, e.g., archiving documents or holding structured meetings and formal conferences help to capture, codify and generate explicit knowledge across the supply chain (Schoenherr et al., 2015; Maravilhas & Martins, 2019). Having more supply chain members with diverse backgrounds and insights into the specific supply chain involved in communication channel can help develop idiosyncratic knowledge (Um & Kim, 2019). Brainstorming and nominal group techniques are well-known methods for facilitating tacit knowledge. The tacit knowledge attributes are consistent with social relations and communities of practice (Schoenherr et al., 2015). A suitable social relationship may positively influence the outcome of the knowledge creation processes since when partners commit to social networks and exchange information in formal or inform channels, they may advance their knowledge along with the social practices (Jiang & Xu, 2020). Knowledge creation is a social process in which partners shift their awareness of tasks, reflect on their experiences, create workbooks to remind themselves of their knowledge base, make inferences by induction, and discuss issues with others (Ganguly, Talukdar, & Chatterjee, 2019). Social practice relationships illustrate that the knowledge creation process captures the interaction between tacit and explicit knowledge that can be socially justified and combined with others knowledge, thus fostering the creation of knowledge. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H3. Relational governance positively affects tacit knowledge in a knowledge creation process.

H4. Relational governance positively affects explicit knowledge in a knowledge creation process.

Supply chain management (SCM) promotes data and information sharing, investment in the capabilities of partners and the sharing of resources (Shahzad et al., 2020; Solaimani & van der Veen, 2021). Further, as business situations become dynamic and uncertain, customers are requiring that firms outperform their competitors. These market conditions have stimulated firms to develop flexibility in the supply chain (Bag, Gupta, & Telukdarie, 2018), so supply chain flexibility (SCF) is required to satisfy stakeholders’ requirements in terms of products’ time, range, volume and innovation.

Over the past decade, information technology (IT) has rapidly changed how supply chains have been implemented and used (Gawankar, Gunasekaran, & Kamble, 2020). Various emerging technologies such as the Internet of things (IoT), big data analytics (DA) and cloud computing are also mitigating the gaps among the organizations (Bag, Pretorius, Gupta, & Dwivedi, 2021). Further, IT usage has produced huge amounts of data, knowledge and information that need to be analyzed using DA tools and techniques in order that supply chain operations are smooth (Hofmann & Rutschmann, 2018). Thus, firms need to manifest smart supply chain solutions for customers based on data analytics, quality management, and knowledge management practices (Gupta, Drave, Bag, & Luo, 2019)

Aboelmaged (2014) posited that electronic maintenance systems should be treated as innovation technology aimed at exploiting diverse knowledge to create strategic value through the heavy use of information and communication technology (ICT) applications. Similarly, supply chain technology, with its integration, synchronization and reliability of applications, can deeply support the delivery and diffusion of new knowledge assets (Schoenherr et al., 2015; Craighead, Ketchen Jr, Jenkins, & Holcomb, 2017). Explicit knowledge constitutes knowledge within a supply chain that can be easily articulated. The effective use and exchange of this readily available explicit knowledge via information technology enhances the efficiency of supply chain, since codified knowledge at one supply chain entity can be easily shared with partners (Brinch, 2018), giving performance improvements. Tacit knowledge is not only difficult to transfer among partners, but may be unique to the specific supply chain and difficult for other partners to replicate (Grant, 1996), due to its tendency to develop within relational interactions (Kahn, Maltz, & Mentzer, 2006). Tacit knowledge focuses on cognitive elements such as individuals’ construction of analogies, experiences, beliefs and perspectives to make sense of available information in complex situations.

Two factors affect knowledge creation in a supply chain: technology adoption and organizational conditions (Cantone, Testa, Hollensen, & Cantone, 2019). New product development requires the merging and integration of different technologies into network strategic communities inside and outside the company so as to share and transfer, thus leading to the creation of knowledge (Cantone et al., 2019). Feller, Parhankangas, and Smeds (2006) examined 105 R&D partnerships in the telecommunication industry, pointing out that a good knowledge transfer mechanism using the novelty of technology developed within the partnership led to better learning results, which, in turn, boosted knowledge creation. Well-known information technology (IT) industry organizations including Samsung, Intel, Google and T-Mobile came together to build the Open Handset Alliance and launch the Android operating system and software platform to allow software developers to easily share information and exchange knowledge, foster the transfer of tacit or explicit knowledge, and create growing technology solutions (Öberg & Alexander, 2019). The ability to use to build, sustain, and extend competitive advantage is important to help IT organizations to achieve an agile supply chain. Internet technologies enhance practices, retain and reuse explicit knowledge and tacit experience in new activities, as well as share formal or informal knowledge and experience. The IoT can be considered a disruptive technology influencing modern firms’ ability to absorb knowledge from external partners. It can also increase their efficiency through new methods of knowledge flow and information gathering (e.g., the internet, intranets, data warehouses, data mining techniques, and software agents), and be used to systematize and formula new knowledge. While studying the integration of IT and knowledge construction to discover new knowledge, Ojha, Struckell, Acharya, and Patel (2018) indicated that supply chain technology can serve a different adjustment degree for both internal and external transfer procedures, which proceed from tacit to explicit knowledge. Qiao, Wang, Guo, and Guo (2021) showed that building information modeling application supported explicit knowledge sharing and innovation capability. Moreover, Kossowska (2007) indicated that cognitive conclusions may be identified, and that knowledge transfer may be achieved through tools and media. Clearly, successful knowledge creation will use common technologies and tools with mutually comprehensible interfaces that support a common view of processes, projects and products (Zouaghi, 2011). Technology can have an essential role in removing blockages to communication and knowledge flow, and therefore enable knowledge creation (Santoro et al., 2018). The transformation of knowledge from tacit to explicit form is a challenging process that can use information technology; for example, ERP or knowledge repository systems can provide the necessary infrastructure to foster new knowledge creation. Accordingly, two hypotheses are proposed below.

H5. Supply chain technology positively affects tacit knowledge in a knowledge creation process.

H6. Supply chain technology positively affects explicit knowledge in a knowledge creation process.

Knowledge management includes mechanisms for sharing and transferring knowledge assets (Maravilhas & Martins, 2019). The goal for knowledge management activities is to apply organizational knowledge to create new knowledge and thus develop and maintain competitive advantages (Gast et al., 2019). This process is related to the social and learning processes in an organization (Arora & Date, 2018). Transforming tacit knowledge into collective explicit knowledge in an organization enables better synergy and more innovation. Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) advocated that tacit knowledge is an important facet of the knowledge-creating organization. From their point of view, an organization creates knowledge through interactions and conversion between tacit and explicit dimensions. In the knowledge creation process, tacit and explicit knowledge mutually complementary because they interact with each other through creative activities of groups and individuals (Nonaka & von Krogh, 2009). Human creativity supports these two different forms resulting in effective interactions, justified observations, defined problems, and their resolutions.

Nonaka and Toyama (2003) presented the dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation, wherein organizational knowledge is created through a continuous dialogue between tacit and explicit knowledge that goes through the interaction processes of, socialization (tacit to tacit), externalization (tacit to explicit), combination (explicit to explicit), and internalization (explicit to tacit). With a faster economic globalization, firms are turning to the knowledge-based economy for essential advantages, making knowledge an even more important resource and source of competitive advantage. With the growing knowledge-based economy, focal firms’ competition has been increasingly replaced by supply chain competition. Supply chains are not only logistical supply chains, but also knowledge supply chains (Schniederjans et al., 2020). Partner firms in a supply chain share knowledge through knowledge transactions and help each other create tacit and explicit knowledge resources, thereby improving competitive strengths and the supply chain's overall competitive advantage. Knowledge creation as a dynamic human process of moderating personal belief toward the truth, and as knowledge essentially related to human action (Jiang & Xu, 2020). It is important for managers to manage tacit and explicit knowledge in partner-organizations of a supply chain. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are put forth.

H7. Tacit knowledge positively affects explicit knowledge in a knowledge creation process.

H8. Explicit knowledge positively affects tacit knowledge in a knowledge creation process.

The knowledge creation process is like an ecosystem that embodies an exchange behavior from the focal firm to its interconnectivity with other parties, so new knowledge is created by interaction rather than only for the firm's own interest (Öberg & Alexander, 2019). Schniederjans et al. (2020) treated ongoing knowledge creation as the core source of continuous innovation and continuous innovation and as the source of sustained competitive advantage. Maravilhas and Martins (2019) argued that when firms innovate, they do not merely absorb outside information to solve existing problems and adapt to a changing environment, but they also gain information and create new knowledge from the inside-out to redefine problems and solutions, thereby re-shaping their competitive environment.

Open innovation developed progressed from obtaining new knowledge and technology-push, through supply chain management to collaboration. It focuses on the free flow of exchanging ideas, experiences, and domain know-how between a ranges of partners. Firms should focus their efforts on gaining or producing new knowledge and innovation for sustained growth. The sustainability of open innovation that is grounded on the flow of knowledge and environmental, social, economic interaction enables the knowledge creation processes for competitiveness in organizations (Lopes et al., 2017). In other words, open innovative capability generated by knowledge creation process can play an essential role for organizational sustainability. According to resource dependency theory, firms need unique, internal resources, skills, and particular knowledge resources to enable sustainable dynamic adaptation and competitive advantage. Firms in a supply chain require access to partners’ knowledge resources and increasingly rely on building and creating knowledge as a necessary condition to achieve business goals. The application of explicit or tacit knowledge alone may not guarantee an effective innovation process, so firms manage their innovation processes to seek novel projects through combining and integrating explicit and tacit knowledge. Both explicit and tacit knowledge generated among supply chain partners are important and the distinction between knowledge types is critical as they may have varying effects on key competitive ability and innovation ability in supply chain performance (Schoenherr et al., 2015). Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed.

H9. Tacit knowledge positively affects open innovation capability in supply chains.

H10. Explicit knowledge positively affects open innovation capability in supply chains.

Data for this empirical study was collected, and the research design is as follows.

InstrumentationThis research questionnaire consists of two parts, as shown in Appendix A. The first collects basic information and the second uses a 5-point Likert scale to measure data for the research model.

Basic informationThe questionnaire collects basic information about organizational characteristics, including industry type, annual revenue, number of employees, number of suppliers, and using supply chain system, as well as respondent characteristics such as age, gender, education level, working experience, and position.

Governance mechanisms and supply chain technologyThe contractual government measurement items are adapted from Sluis and De Giovanni (2016), with 3 items. Relational government is measured by 4 items adapted from (Huang & Chiu, 2018). The measurement items for supply chain technology were adapted from Kim and Chai (2017), and include 4 items.

Knowledge creation processBoth explicit knowledge and tacit knowledge measurements are adapted from Papa, Santoro, Tirabeni, and Monge (2018). The instrument consists of 3 items and 4 items, respectively.

Open innovation capabilityMeasurement items are adapted from de Araújo Burcharth, Knudsen, and Søndergaard (2014), including 4 items.

Sample designThis study examines the influence of the knowledge creation process on the development of open innovation capability in the supply chain. Firms suitable for this study should stress investment in supply chain technologies and have supply chain experience with trading partners. The study samples were 300 manufacturing and 300 service companies randomly picked from Taiwan's top 1000 service and manufacturing organizations in 2019. Target respondents were the administration and R&D supervisor as well as R&D and logistics executives, who are more involved with inter-firm open innovation activities among trading partners. This survey was conducted from May to July in 2019. We mailed the questionnaire with a return envelope to one top manager for every firm, so each firm received only one questionnaire. To increase the survey return rate, a reminder letter or an interview request for the target responses was sent to non-respondents after 6 weeks. We also used a reward system of 5 US dollars for the respondents to help increase the response rate collected during the document papers or online survey process.

Sample demographicsThe pretest was examined by invited practitioners and academicians in this area, for aspects including translation, wording, structure, and content. The content validity of the scale had to be at an acceptable level. After the questionnaire was finalized, 600 questionnaires were sent out to potential respondents. A total of 143 responses were received. After invalid responses were deleted, there was a sample size of 140, for a response rate of 23.33%. Table 2 shows the sample demographics. The seemingly low response rate raises concern about non-response bias. Common method bias results from the fact that the respondents provide the measures of explanatory and dependent variables by a common rater Jarvis, MacKenzie, and Podsakoff (2003). In this study, subjective measures were used for five sets of variables, contractual governance, relational governance, supply chain technology, explicit knowledge, and open innovation capability.

Demographics.

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Industry type | ||

| High-tech Manufacturing | 25 | 17.9 |

| Traditional Manufacturing | 53 | 37.9 |

| Service | 33 | 23.6 |

| Others | 29 | 20.7 |

| Annual revenue | ||

| <1000M | 14 | 10.1 |

| 1000∼10000M (less than) | 24 | 17.1 |

| 10000∼50000M (less than) | 16 | 11.4 |

| 50000∼10000M (less than) | 4 | 2.9 |

| ≧100000M | 82 | 58.6 |

| No. of employees | ||

| <500 | 80 | 57.2 |

| 500∼1000 (less than) | 6 | 4.3 |

| 1000∼5000 (less than) | 15 | 10.7 |

| ≧5000 | 39 | 27.9 |

| No. of suppliers | ||

| <10 | 17 | 12.1 |

| 10∼50 (less than) | 40 | 28.6 |

| 50∼100 (less than) | 17 | 12.1 |

| ≧100 | 66 | 47.1 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 106 | 75.7 |

| Female | 34 | 24.3 |

| Age | ||

| <30 years | 13 | 9.3 |

| 30-40 years (less than) | 37 | 26.4 |

| 40-50 years (less than) | 49 | 35.0 |

| ≧50 years | 41 | 29.3 |

| Working experience | ||

| <10 years | 40 | 28.6 |

| 10∼20 years (less than) | 44 | 31.4 |

| 20∼30 years (less than) | 36 | 25.7 |

| ≧30 years | 20 | 14.3 |

| Education level | ||

| High school | 6 | 4.3 |

| College | 42 | 30.0 |

| Graduate school | 92 | 65.7 |

| Position | ||

| Logistics executives | 17 | 12.1 |

| R&D executives | 17 | 12.1 |

| R&D Supervisor | 39 | 27.9 |

| Administration Supervisor | 67 | 47.1 |

PLS was used to analyze the research model. First, a measurement model was built for scale validation and a structural model for path analysis. The measurement model included two steps. The first step assessed reliability by a Cronbachel α larger than 0.7 (Chin, 1998). Convergent validity had three criterions: average variance extracted (AVE) greater than 0.50, composite reliability (CR) greater than 0.80, and item loading (λ) greater than 0.70. (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The second step, for discriminant validity, used the criterion that the square root of AVE for each construct must be larger than its correlations with other constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). As indicated in Table 3, AVE ranges from 0.55 to 0.89, CR ranges from 0.88 to 0.96, and λ ranges from 0.74 to 0.96, indicating that all constructs have high reliability and convergent validity. The square root of AVE for each construct is greater than its correlations with all other constructs (see Table 4), so all the constructs fit the criteria of discriminant validity. In addition, the study also presents a full cross-loading table using CFA, as shown in Appendix B, to test the convergent and discriminant validities.

Reliability and convergent validity.

| Construct | Num. of Items | Item means | Standard deviations | Item loadings | AVE | Composite reliability | Cronbach’α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG | 3 | 4.07 | 1.00 | .94 - .96 | .89 | .96 | .94 |

| RG | 4 | 4.11 | 0.75 | .81 - .90 | .74 | .92 | .88 |

| ST | 4 | 3.64 | 1.08 | .83 - .93 | .74 | .92 | .88 |

| TK | 4 | 3.87 | 0.89 | .86 - .92 | .78 | .93 | .91 |

| EK | 3 | 3.53 | 1.01 | .84 - .95 | .81 | .93 | .88 |

| OIP | 4 | 4.11 | 0.88 | .74 - .78 | .55 | .88 | .84 |

Contractual governance (CG), Relational governance (RG), Supply chain technology (ST), Explicit knowledge (EK), Open innovation capability (OIP).

There is a risk of bias generated by common method variance (CMV) in self-reported data due to subjective judgment utilizing a similar degree for both antecedent and dependent variables Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, and Podsakoff (2003). This study adopts the marker technique of confirmatory factor analysis to check for CMV (Williams, Hartman, & Cavazotte, 2010). We also implement preventive remedies by requiring the subjects not to evaluate open innovation capabilities based on personal experience, but to rely on their official papers (Podsakoff & Organ, 1986). By creating a labeled variable related to all indicators of substantive variables and including it in the PLS model, we calculate the variance of each indicator noticeably explained by the main structure. As result in Appendix C, CMV information is found from a comparison of the variances of all indicators of substantive variables (R12) and the marker variable (R22) since R1 and R2 are the factor loadings for the two types of variables. The findings display a difference with the average substantively explained variance of the indicators is 17.759, while the average method based variance is .412. The ratio of substantive variance method variance is approximately 43:1 and all factor loadings of the marker variable indicate no statistical significance. Thus, in terms of both results of the marker variable, CMV is not a concern.

The study uses a specific sampling design to increase the sample representativeness. In addition, we performed a non-parametric test by the Mann Whitney rank-sum. The study splits the response sample into two independent groups consistent with a random sampling procedure (Henseler et al., 2014). The two groups were verified for their correlation in terms of some properties, containing company type, and revenue. All the correlations demonstrate non-significant dissimilarity, specifying independence, so the response sample is well representative of its population. Mentzer and Lambert (2015)suggested that the Chi-square test could be used to test for non-response bias. The result of Chi-square tests here shows no significant differences between the two groups (before and after 6 weeks) in either of the variables (p-value > 0.05). Thus, there appears to be no non-response bias, as shown by the test results in Table 5.

Hypothesis testingOur research model was based on structural equation modeling (SEM) for which Partial Least Squares (PLS) is a popular method for SEM. Thus, we employed PLS-SEM for our research model. PLS uses a component-based and nonparametric method for estimation which is quite suitable for this research model. We established a measurement method to validate scale and built an SEM model for path analysis. The model has two steps: the first evaluates both the reliability and convergent validity, while the second step checks the discriminant validity.

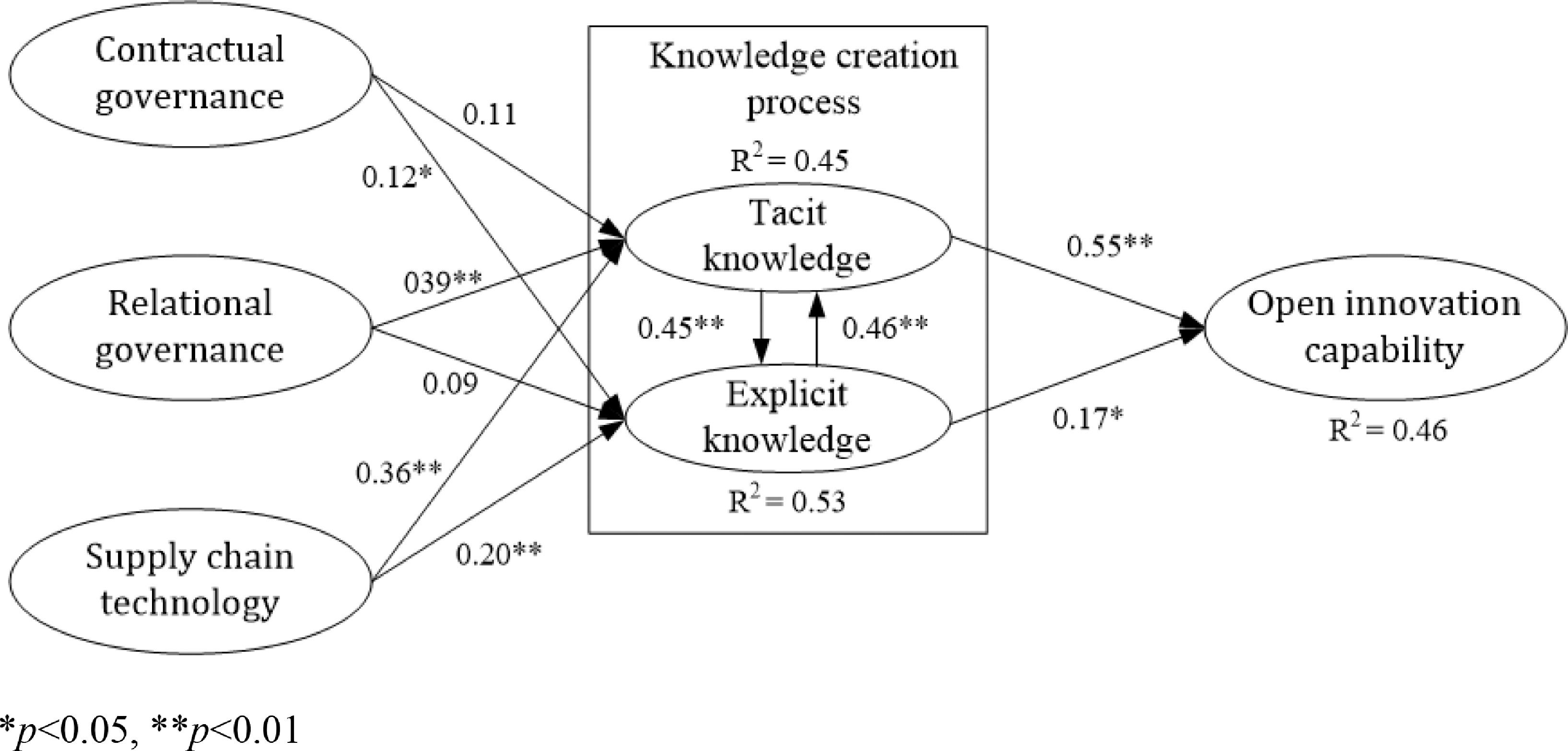

Bootstrapping analysis was performed with 1000 subsamples to estimate the path coefficients and significance tests. In this study, there is a recursive relationship for two constructs, tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge, so the examination procedure was executed twice for each of the two directions, separately. The recursive relationship of the path coefficients is slightly different (β=0.45⁎⁎ and β=0.46⁎⁎) since the other path coefficients have similar measurements for the two implementations. Path results of the structural model are shown in Fig. 2. Henseler (2017) introduce the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) as a goodness of fit measure for PLS-SEM that can be used to avoid model misspecification. This SRMR value less than 0.1, or 0.08, is considered a good fit (Henseler, 2017). The SRMR values of this study were 0.07 (saturated model) and 0.08 (estimated model), both of which are less than 0.1, indicating that the model fits well in this study.

In the inter-organizational relationships (IOR) issues, we found that contractual governance is not reported as an important predictor of tacit knowledge but explicit knowledge is (p>0.05, β=0.11; p<0.05, β=0.12). Thus Hypothesis 1 is NOT supported and Hypothesis 2 is supported. Relational governance is shown as an important predictor of tacit knowledge but not explicit knowledge (p<0.01, β=0.39; p>0.05, β=0.09). Hypothesis 3 is supported and Hypothesis 4 is thus NOT supported. In the supply chain technologies, we found that technology use is as important predictor of tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge (p<0.001, β=0.36; p<0.001, β=0.20). Hypotheses 5 and 6 are thus supported.

In the knowledge creation process, we estimate the path coefficients and significance tests of tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge, respectively. We found the path coefficients and significance tests of tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge are both significant (p<0.01, β=0.45; p<0.01, β=0.46). They are interrelated and can enhance open innovation capability. Hypotheses 7 and 8 are thus supported. The three variables, contractual governance, relational governance, supply chain technology, jointly explain 45% and 53% of the variance in tacit knowledge (R2=0.45) and explicit knowledge (R2=0.53), respectively. In turn, tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge, as important knowledge creation processes in supply chain, significantly influence focal firm open innovation capability (p<0.01, β=0.55; p<0.05, β=0.17). Hypotheses 9 and 10 are thus supported, and they explain 46% of the variance in focal firm open innovation capability (R2=0.46). Table 6 summarizes the results of hypotheses testing.

Hypotheses testing results.

| Hypothesis | Decision |

|---|---|

| Hypothesis 1 for contractual governance and tacit knowledge | Not supported |

| Hypothesis 2 for contractual governance and explicit knowledge | Supported |

| Hypothesis 3 for relational governance and tacit knowledge | Supported |

| Hypothesis 4 for relational governance and explicit knowledge | Not supported |

| Hypothesis 5 for supply chain technology and tacit knowledge | Supported |

| Hypothesis 6 for supply chain technology and explicit knowledge | Supported |

| Hypothesis 7 for tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge | Supported |

| Hypothesis 8 for explicit knowledge and tacit knowledge | Supported |

| Hypothesis 9 for tacit knowledge and open innovation capability | Supported |

| Hypothesis 10 for explicit knowledge and open innovation capability | Supported |

The three major issues of contractual governance, relational governance and supply chain technology show different effects on the knowledge creation process. In particular, they are major precursors in forming tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge. Thus, the three components all partly influence the knowledge creation process. In contrast, neither of the IOR issues, contractual governance and relational governance, shows as strong effects as supply chain technology in tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge. The contractual governance element is partially an effect of significance on the knowledge creation process. The relational governance element is partially an effect of significance on the knowledge creation process. These are significant findings of this study.

In supply chains, organizational knowledge, especially tacit knowledge, is often accumulated in practice over a long period time, so the focal firm may be unwilling to share it with partners without compensation. In an increasingly competitive organizational environment, the competitive pressures experienced by organizations make them believe that the knowledge they possess is a guarantee of their value and position in their industry. If the focal firm shares the knowledge that it possesses to supply chain partners, it will lose it advantages, and without a unique competitive advantage, the focal firm's own interests cannot be guaranteed.

Previously, in the process of research and development it was not possible to collect a large number of user needs. On the other hand, it was not easy for the interviewee to truly represent the target customer market. Although some large foreign companies such as Procter & Gamble and BMW have been successful in product design and development. However, most successes when the focal company to conducts research and development by directly collecting the needs of consumers or asking retailers to help collect feedback from users, rather than sharing business intelligence with supply chain partners specifically and directly. Each supply chain member still insists on maintaining intellectual property rights and patented technology to consolidate its market position.

From the governance mechanism perspective, for explicit knowledge, Jia et al. (2020) indicates that the contractual background includes operational procedures, checkpoints for each task, rights and obligations of supply chain partners, how to share profits, etc. Although the contract governance mechanism can establish an agreement detailing the obligations of partners or define some events of an accident, it is still difficult to comprehend the entire supply chain and make a complete rule base that protects against all risks. Although both of the parties need to obey business rules to deliver the operational document, product manual or service manual, applying contractual control can promote long-term relationship building and enhance performances (Sluis & De Giovanni, 2016). This is, firms may design a feasibility contract (maybe incomplete contract) to maintain a good relationship. This means that contract control helps build the relationship and define high-level negotiations processes when the parties encounter problems. Hence, contract control may be an effective way to develop an effective communication mechanism to exchange explicit knowledge as well as tacit knowledge.

From the supply chain technology perspective, effective supply chain techniques for building, maintaining and expanding knowledge resources are important to help partners exchange knowledge and create new ideas. Advanced technologies, such as cloud computing, lead to financial and operational benefits by providing infrastructure, platforms and software solutions for supply chain networks to support optimization.

From the knowledge creation process perspective, the disclosure of tacit knowledge cannot be obtained through standard contracts government mechanism, but it can be engaged by using information technology and data analysis to explore potential data patterns, along with data models to create business opportunities. In addition, a good partnership has a significant developmental impact on the acquisition of tacit knowledge. That means that if the focal firm can establish trusting, reciprocal, cooperative and long-term partnerships in the supply chain, that will help other business to learn how to acquire know-how from the tacit knowledge of supply chain partners.

From the open innovation capability perspective, knowledge resource is the central principle for creating competitive and flexible supply chains for the target in the final goal of open innovation capability. This study finds that creating both tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge is an important mediator in achieving focal firm open innovation capability from a combination of different sets of drivers. Since partners in the supply chain tend to be more satisfied with their knowledge exchange behaviors, they will effectively eliminate waste (time and material), both internally and externally, and can focus on their core competencies. As a result, fostering open innovation capability is expected from the effort of exchanging tacit and explicit knowledge. That is, both knowledge indicators are in a position to properly explain focal firm open innovation capability which links inside and outside flows of knowledge by working within associations of complementary companies.

The differences between the strengths of influence are as follows: Contractual governance has significant influence on explicit knowledge (β=0.12); while relational governance has significant influence on tacit knowledge (β=0.39). This is quite intuitive in the sense that contracts are more explicit, while relationships are more tacit. Thus, these two kinds of knowledge creations are individually affected by the two kinds of governance separately. However, our research results show that supply chain technology influences both tacit and explicit knowledge (β=0.36 and β=0.20, respectively). We could conclude from this initial observation that supply chain technology has introduced a wider range of knowledge creations than conventional governance mechanisms, which could only influence one kind each. Nevertheless, comparing the effects of relational governance and supply chain technology on tacit knowledge, β=0.39 and β=0.36 respectively, shows that conventional relational governance still has more influence on tacit knowledge creation, than that of supply chain technology. This is also quite intuitive in that relational governance is still the core of interactions and collaborations among partners, and not the means of efficient collaboration, as introduced by supply chain technology. In other words, supply chain technology merely aids in better communication and cooperation across partners, and collaboration content is still dependent on the relational aspects across the stakeholders. With open innovation, it is clear that tacit knowledge has a much more prominent impact on open innovation (β=0.55) than that by explicit knowledge (β=0.17). This is also a major contribution of our research results, demonstrating that open innovation could be promoted through efficient communications of good relationships, and not merely by fixed contractual governance. In summary, open innovations could be fostered through good relationships for collaboration across partners, along with the efficient means of communication and services in supply chain technologies.

Theory contributionsThis research concerns an overall conceptual understanding of collaborative innovation and knowledge creation process in the supply chain. Specifically, we define key antecedents of the knowledge creation process from inter-organizational and IT perspectives. This is critical since open innovation activities in the supply chain have been considered an essential requirement for a firm's competitive ability. We utilize transaction cost theory (TCT) and social exchange theory (SCT) as the theoretical basis to define our solution model. This proposed model also contributes to an extension of existing research by examining the three key issues of contractual governance, relational governance and technology concern, as the main drivers in the relationship structure. They are found to significantly relate affect knowledge creation for open innovation capability in the supply chain. An elaboration for the research model is associated with the governance mechanisms, contractual governance and relational governance of knowledge creation process in supply chain. Little research has been reported for this integration, making it a theoretical contribution for the research. The results show: (1) the influence of three major issues, contractual governance and relational governance, and technology facilitation on explicit knowledge and tacit knowledge in supply chain practice; (2) knowledge creation process mediates the relationship between the precursors and open innovation capability and leads to a high prediction for open innovation capability. This is a practical contribution to related research.

Managerial implicationsThis research explores open innovation capability in supply chains. Since a high proportion of open innovation capability is critical for sustainability of the supply chain, this research reveals the importance and great impact of the benefits of supply chain partners on business activities. In general, by paying close attention to understanding the interaction behavior in supply chain, firms can decrease cost, generate more ideas to create great economic value for the organization, and create many job opportunities for society. To elaborate on the research, we focus on a major concern of determining firms’ open innovation capability through knowledge creation process, that is, contractual governance, relational governance and supply chain technology use. Contractual governance would see formal relationship as making promises to partners by establishing written business activity rules. Relational governance is the role of enforcing commitments, obligations, promises, activity expectations, and common goals that occur through trust and social identification when performing business collaboration activities. An effective supply chain technology for building, sustaining, and extending knowledge resources is important to help organizations exchange knowledge and create new ideas in a supply chain. Finally, companies could take this as a basis to plan and design their own knowledge creation platform and to foster the ability of open innovation and benefits in an effective manner. It is noteworthy that advances in information technology have begun to emphasize cloud computing. Cloud computing supports optimization by providing infrastructure, platform, and software solutions for supply chain networks, leading to financial and operational benefits. Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) has been the best cloud computing practice for supply chain management. Further, cloud computing offers Geo Analytics, location-based information for contextual awareness, allowing SCM professionals to monitor delivery networks, resolve bottlenecks, and prioritize slower moving shipments. Thus, cloud computing can serve as data warehouse, deliver savings and stronger returns, and significantly enhance agility and resilience. Open innovation for SCM helps to integrate people, machines, and information systems so that technology advancements can be achieved via internal and external ideas. Such integration can often be achieved via cyber-physical systems that require cloud computing services (Shcherbakov & Silkina, 2021). Christensen, Olesen, and Kjær (2005) showed how open innovation can be analyzed from an industrial dynamics perspective, considering measures that companies take to manage open innovation, the nature and stage of maturity of the technology, and the particular value proposition pursued by companies. A model for open innovation Yun, Kim, and Yan (2020) was targeted for exploring existing open innovation channels, which can be useful to motivate engineering research to increase the development of open innovation and new open business models. Cloud computing has a major role in such open innovations for SCM.

Limitations and future research directionsAlthough this study has important findings, some limitations should be noted. The randomness of the sample is one issue, though we used a method to process the sampling procedure, and also to perform a representative test to ensure this population with a better improvement. In addition, there are 75.7 % of subjects are male, which is unlike the overall population distribution and may unfairness the survey results. It means, while more women involve the workforce, it will be possible to change the company's culture, organizational strategy and thinking mode, which will affect the open innovation capability of the supply chain.

To better understand factors affecting open innovation capability in the supply chain, future research can extend to other perspectives, such as different organizational cultures and leadership styles, or the management of public and private units. In particular, when improving the overall supply chain innovation ability, a smooth knowledge conversion process is helpful for a company's sustainable development. How to improve the efficiency and mechanism of knowledge conversion and the application of information technology tools can be a measurement of performance indexes. For example, the amount of tacit knowledge converted into explicit knowledge, how to improve the operation process by using explicit knowledge.

ConclusionFocusing on the organizational level, this study finds that rich knowledge resources are the key factor to promote open innovation capability in supply chains. The key influencing factors of the knowledge creation process include the different governance mechanisms and the supply chain technology used. These viewpoints can be widely applied to various industries to enhance the open innovation capability of the supply chain, for example, how to develop a series of innovation processes related to the ecosystem, and use incubation centers to foster promising projects; or create a more open atmosphere to reduce costs and expand participating suppliers, thereby improving the overall supply chain.

FundingThis work was supported by the National Science and Technology Council [Grant no. NSTC 107-2410-H-218-014-MY2], Taiwan.

- 1.

Industry type

- 2.

Annual revenue (NT$ millions)

- 3.

Number of employees (persons)

- 4.

Number of suppliers

- 5.

Using supply chain system

- 6.

Gender

- 7.

Age

- 8.

Working experience (years)

- 9.

Education level

- 10.

Position

On a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) please indicate the degree of the following scale items:

- 1.

Supply chain partners have a specific, well-defined agreement.

- 2.

Supply chain partners have customized agreements that detail the obligations of both parties.

- 3.

Supply chain partners have detailed contractual agreements specifically designed.

- 1.

Supply chain partners are trustworthy.

- 2.

Supply chain partners have always been fair in their negotiations.

- 3.

Supply chain partners keep their promises of making.

- 4.

Supply chain partners have a good reputation and is dependable.

- 1.

Supply chain systems have a user-friendly interaction with all partners.

- 2.

Supply chain technology, such as Internet of things (IoT), provides a good communication.

- 3.

Supply chain technology, such as cloud computing, provides well-integrated data across partners.

- 4.

Supply chain information security affects our decisions to communicate in the supply chain.

- 1.

Supply chain partners plan strategies by using published literature.

- 2.

Supply chain partners create manuals and documents on products or services.

- 3.

Supply chain partners build databases on products or services

- 1.

Supply chain partners gather information from sales and production sites.

- 2.

Supply chain partners search and share new values and thoughts with other members.

- 3.

Supply chain partners try to develop common vision through communication with other members.

- 4.

Supply chain partners conduct experiments and share results with other members.

- 1.

Supply chain partners capably convert acquired ideas of other partners to create innovations.

- 2.

Supply chain partners regard acquired ideas of other partners as valuable to improve innovations.

- 3.