Digital transformation has far-reaching effects on business and society. While the literature to date has mainly considered the positive opportunities associated with digital innovations at the consumer interface in terms of products and services, the impact on asset-intensive organisations has not yet been examined in detail. Because asset-intensive organisations have unique requirements, a focused approach is essential. This study provided an in-depth analysis of digital transformation efforts in asset-intensive organisations by interviewing elite informants in the field. Our results provide an explanatory model for the digital transformation of asset-intensive organisations from a dynamic process perspective. Our results also allowed us to uncover the dark side of digital transformation, and we theorise on its implications.

Digitalisation and globalisation have been considered the two most important disruptions in strategic management in the last 40 years, through the transformation of firms’ business models (Loonam et al., 2018; Rachinger et al., 2018). In this research, we focused on the first phenomenon. Digital transformation (G. Vial, 2019) offers the greatest market-changing potential because it enables not only the development of innovative products and services (Hess et al., 2016) but also of innovative processes, tools and mechanisms to create and capture value (Gölzer & Fritzsche, 2017; Li, 2020; Matt et al., 2013; P.C. Verhoef et al., 2021). Some of these innovations include novel technological solutions, for example, artificial intelligence (AI) or quantum computing, as well as more diffuse technologies, such as social media, mobile computing, advanced analytics and cloud computing (Fitzgerald et al., 2013; Schoeman & Moore, 2019). While much has been written about digital transformation (G. Vial, 2019), the underlying literature has two important omissions. First, it predominantly assumes that digital transformation presents only positive impacts for organisations (H. Trittin-Ulbrich et al., 2021). Second, past literature in digital transformation is largely focused on companies that build products and services for end-consumers (P.C. Verhoef et al., 2021).

However, for specific industries which are far from consumers, digitalisation might have an important ‘dark side’, and the opportunities for digital transformations in these industries are very different. Especially in asset-intensive industries, digital transformation comes with major strategic and organisational challenges (Loonam et al., 2018). Asset-intensive organisations—most of which have decades of tradition, a long-lasting legacy and have experienced stable market conditions over a long period of time—rely to a large extent on an extensive asset base and require significant investments in non-digital resources (Gao et al., 2019; Sivapalan & Bowen, 2020; Vishnevskiy et al., 2017). The impacts of digital transformation (positive and negative) are of even higher importance because they often have strategic relevance for entire economies with far-reaching geopolitical considerations. In Australia, for example, the mining and mineral sector represents a 10.4% share of the economy (Casey, 2021; Constable, 2020) and accounted for 21.4% of Australians who were hired in the mining sector between 2016 and 2020, amounting to a total figure of 261,900 employees (Casey, 2021). The important role of the mining sector in Australia's economic development has made the mining sector move towards intense digitalisation to drive productivity and improve miners’ safety and health (Young & Rogers, 2019). The sector has already started to use several digital technologies, like drones, to avoid time-consuming and dangerous manual exploration. Rio Tinto, a mining corporation, is using automation technology in Australia's Pilbara and has achieved an improvement of 10–15% in the use of automated drills alongside improved safety, better maintenance, lower energy use and greater operational precision (Australian Government, 2018; Manyika et al., 2017). Nevertheless, asset-intensive organisations have longer project life cycles and work with large physical assets (e.g., mines) and technologies (e.g., oil rigs) that are not easy to move or transform (Humphreys, 2020). Also, health, safety and environmental considerations play critical roles in how they must conduct projects, adopt technologies and innovate (Carvalho, 2017; Jang & Topal, 2020; Sánchez & Hartlieb, 2020).

Due to the central economic position and special characteristics of asset-intensive industries, the impact of digital transformation—both positive and negative—needs to be completely re-contextualized, researched and understood. Compared with some consumer-centred organisations, the business purpose of asset-intensive organisations can only be extended and not replaced. Thus, we cannot simply import knowledge on digital transformation efforts from other sectors (e.g., finance, consumer products, etc.). These organisations that operate further from consumer interaction and often have a very large asset base (e.g. fixed infrastructure and heavy equipment) are rarely considered in the context of digital transformation due to the cost and risks involved (Björkdahl, 2020). The major challenges for asset-intensive organisations in digital transformations are also reflected in industry-wide deficiencies with regard to the digitalisation process (Gao et al., 2019) and lower scores on the Digital Intensity Index (European Commission, 2020), revealing notable pitfalls in the process of digital transformation. Although research shows that asset-intensive organisations, in particular, have different barriers, such as inertia and resistance, an in-depth strategic digital transformation analysis has not yet been carried out (Björkdahl, 2020; Gao & Hakanen, 2020). However, knowing more about digital transformation is important for asset-intensive organisations because they belong to industries that are critical to many economies, and many savvy digital companies are eager to step into their market (Macdonald-Smith, 2019).

We posit that digital transformation has the potential to alter asset-intensive organisations at their core, but this needs to be done in a unique and strategic way so that the firm's core value is not jeopardised. This is the focus of the current research. However, for such change to happen, a highly context-dependant corporate behaviour (E. Autio et al., 2014; Welter, 2011; S.A. Zahra et al., 2014) is needed to shock the firm's organisational identity through a disruptive innovation (Altman & Tripsas, 2015;N. Kammerlander, Nadine König, Andreas Richards, Melanie, 2018). This creates a theoretical tension that serves as our theoretical ground. Thus, we ask: how are asset-intensive organisations conducting digital transformation efforts, and what are the opportunities and challenges they face with such transformation?

To answer our research question, we undertook a qualitative approach. Specifically, we conducted interviews with elite informants at seven leading asset-intensive organisations with operations in Australia. Based on the analysis of the interviews with elite informants, we derived a dynamic process model for digital transformation for asset-intensive organisations. Our work makes three theoretical contributions to the study of digital transformation in asset-intensive organisations—a phenomenon that has fundamental relevance for the future development of many economies. First, we showed that asset-intensive organisations diverged on their digital transformation and evaluated its potential from a long-term strategic dimension instead of from the angle of developing new products and services, as past research has found for non-intensive industries (P.C. Verhoef et al., 2021). Second, asset-intensive organisations extensively considered the possible dark sides and, thus, carefully weighed the scenarios with positive and negative impacts of digital transformation because of their unique context and organisational identity. Third, our results pointed to a focus on new processes and business models rather than new products or services, which allowed us to theorise on the context-dependant nature of digital transformation, thus adding to the body of research on the role of context in corporate behaviour research (e.g., E. Autio et al., 2014; S.A. ). Our derived dynamic process model not only informs theory but also supports practitioners by understanding the digital transformation of asset-intensive organisations due to their unique prerequisites and position in the economy. Thus, practitioners, both from incumbents and new market entrants, can purposefully strategise how they want digital transformation to thrive in asset-intensive industries.

BackgroundDigital transformation and industry 4.0Digital transformation is an important phenomenon for scholars (A. Bharadwaj et al., 2013; Piccinini et al., 2015; P.C. Verhoef et al., 2021) and practitioners in various industries (Fitzgerald et al., 2013; Gimpel et al., 2018; Westermann, 2016). Nevertheless, existing literature still offers somewhat ambiguous definitions of what constitutes digital transformation (Kraus et al., 2022; G. Vial, 2019). Incumbent organisations, particularly from manufacturing-driven and asset-intensive industries, struggle with the transformation of their businesses into a digital era (Jones et al., 2021; Morakanyane et al., 2020; Vogelsang et al., 2018).

Incumbent organisations especially face numerous challenges because digital transformation is seen as the fourth industrial revolution (Schwab, 2016; Thomson, 2018), which comes with the intersections of digital technology, biological and physical systems that will potentially force all industries to undergo a holistic organisational transformation by the means of digital technologies (Jones et al., 2021). The integration of digital technology subsequently enables changes in the value-creation paths of an organisation (Fernandes et al., 2022; Wessel et al., 2021), seen in four dimensions. These dimensions include the use of technologies, value creation changes or business model readiness, changes in company structures and financial facets (C. Matt et al., 2015; Tavoletti et al., 2021; Tekic & Koroteev, 2019). The implementation of digital technologies provides considerable opportunities for organisations to expand their competitive advantage by allowing them to create and enhance their digital capabilities (Grover, Varun Kohli, Rajiv Ramanlal, Pradipkumar, 2018). In other words, digital transformation can be considered to be how a company creates, conveys and seizes value as an entrepreneurial endeavour (Björkdahl, 2020; Fernandes et al., 2022; C. Matt et al., 2015). The associated structural changes embrace adaptations in a company's organisational operation and process, particularly regarding the employment of the new digital technologies across the corporation (C. Matt et al., 2015).

In an industry context, digital transformation is closely associated with the paradigm of Industry 4.0. Based on digitization, automation and interconnection, Industry 4.0 is a paradigm shift and is described as the next industrial revolution (Liao et al., 2017) that will account for the development of intelligent and connected factors of production (Thoben et al., 2017). The core of Industry 4.0 is related to the integration of information and communications technology and, thus, it is limited mainly to manufacturing process improvements that are enabled by smart manufacturing (Björkdahl, 2020; Schumacher et al., 2016).

However, the integration of physical objects, intelligent machines, human actors, processes across economic agents and institutions, and product lines affects many other functions beyond the manufacturing process (Björkdahl, 2020; Danuso et al., 2022). The goal of Industry 4.0 is to interconnect resources, information, objects and human beings to create industrial value (Kagermann & Wahlster, 2013) and increase firm performance (Ferreira et al., 2019). The design principles of Industry 4.0, which are the building blocks of digital transformation, enable industrial value chain members to achieve the advantages promised by digital transformation and the Industry 4.0 transition (Ferreira et al., 2019; Indri et al., 2018). Digital transformation under Industry 4.0 is described as implementing digital technologies to create value (Danuso et al., 2022; Frank et al., 2019; Indri et al., 2018). Digital networking of supply chains and customers facilitates data exchanges and analyses that create benefits for partners; this process is referred to as horizontal integration in Industry 4.0 (Kiel et al., 2017). Therefore, supply chains can increase flexibility, and decision-making becomes optimized (Veile et al., 2020).

Additionally, Industry 4.0 paves the way to develop and market highly customized innovative products and services (Yoo et al., 2012). In addition to horizontal integration, vertical integration within a company is also the aim of Industry 4.0 (Veile et al., 2020). Here, individual departments grow together virtually from product development to operations management to marketing and sales (Veile et al., 2020). This requires a different organizational change and culture as well as interdisciplinary thinking and overcoming social challenges within a company during the transformation process (Kiel et al., 2017). The digital transformation within Industry 4.0 is a strategic business change that institutionalizes and integrates various combinations of modern information and communication technologies, such as AI, data analytics, digital twins, industrial robots and blockchain. This procedure involves the adoption of agility, customer orientation and product individualization as core competencies (Fatorachian & Kazemi, 2018).

Asset-intensive organisations and their corporate behaviour context and organisational identityAsset-intensive organisations are mature organisations with a long-lasting legacy (Chiaroni et al., 2010; Gao et al., 2019; Vishnevskiy et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2013). These firms ‘require significant levels of capital investment in their physical assets to operate’ (Sivapalan & Bowen, 2020, p. 2). Asset-intensive organisations are traditionally engaged in global value chains and have other businesses as their customers; they very rarely engage directly with consumers (Gebauer et al., 2020).

Most asset-intensive organisations have witnessed stable market conditions over a long period of time, rely to a large extent on an extensive asset base and require significant investments in non-digital resources (Gao et al., 2019; Sivapalan & Bowen, 2020; Vishnevskiy et al., 2017). Given the low level of industry dynamism, firms in this sector do not experience significant direct pressures from their customers. Because asset-intensive organisations operate based on a largely non-digital resource base, consisting of heavy physical assets and technologies (e.g., mines and oil rigs), and they rely on long project life cycles, they are seen as a unique industry, which requires a differentiated analysis when it comes to digital transformation. Given that the business purpose of asset-intensive companies cannot be replaced digitally (physical raw materials cannot be digitised) but can only be expanded, these companies must, on the one hand, exploit their existing resources and, on the other, fundamentally explore their business models.

Their unique situation results from the fact that they cannot completely abandon their existing business model due to the existential dependency on raw materials, and their digital transformation will, therefore, always be linked to their asset base. Due to their unique position in an economy, their special resource endowment and their complete business-to-business character, the digital transformation in asset-intensive industries must be examined separately. Compared with other industries, asset-intensive industries demonstrate two major differences. Asset-intensive industries have a very specific and, so far, clearly defined value proposition. For example, mining companies see their value proposition in the extraction and delivery of raw materials (Humphreys, 2020).

While digital transformation can lead to an increase in efficiency and, thus, lead to innovation in exploitation, the evolution of explorative innovation is not obvious compared with industries like finance and health care which have the opportunity to create value at the consumer interface (Lakshmanan et al., 2019; Lala et al., 2016). In addition, and caused by the concentration on the primary value proposition, asset-intensive companies are confronted with a very encrusted corporate culture that is difficult to break down (Gao et al., 2019; Lavikka et al., 2018). Consequently, decision-makers in the industry ‘lack knowledge about the implementation of digitalisation to generate value’ (Lavikka et al., 2018, p. 635).

The literature in the corporate behaviour context (E. Autio et al., 2014; Welter, 2011; S.A. Zahra et al., 2014) helps to explain such roadblocks from a theoretical perspective. Therefore, while insights from other industries should be incorporated into the digital transformation of asset-intensive industries, the uniqueness of such an industry must be considered. Concomitantly, the organisational identity literature (Altman & Tripsas, 2015; Gioia et al., 2013) portrays strong organisational identity as being a potent preventer of change (e.g., Kogut & Zander, 1996). That said, a recent literature review by Callen and Tripsas (2016) explained that when members of an organisation perceived the benefits of a transformation activity as ‘identity enhancing’ for the organisation and themselves, then they were more likely to pursue such a transformation.

This might help to explain that today we are beginning to see digital innovations reshape firm operations in asset-intensive industries. CEMEX, a leading provider of cement with a distribution network that spans several continents, is an excellent example of this idea in action (Özcan et al., 2018; Zaki, 2019). Through the company's Smart Silo initiative, digital technologies have made it possible for the company to streamline processes, increase knowledge of customers’ use of products, and better manage their assets and engineering workflows. CEMEX installs sensors directly on customer assets to track inventory and usage and then runs analytics on data from sensors to anticipate customer demand and proactively supply cement to customer sites. Initiatives such as these result in lower wastage of engineering resources, better coordination across supply chains and optimised asset management.

Moreover, and more recently, new digitally-savvy tech start-ups are beginning to apply pressure to asset-intensive organisations (Boyle, 2019; Chen, 2020; Macdonald-Smith, 2019). Digital native firms like IBM, Google and Apple are entering the mining sector and driving an upheaval in efficiency by providing smart mines, which might provide a disruptive potential in the industry. Finally, there are pressures faced by these firms from their business partners or investors, for example, to be more environmentally sustainable or to be more connected with others in the global value chain (Apple Inc., 2018; Toscano, 2019). There is scant literature on how digital transformation is happening in asset-intensive industries, such as water and power utilities, mineral resources, metals, mining energy, shipbuilding and manufacturing (Björkdahl, 2020; Gao et al., 2019; Sivapalan & Bowen, 2020; Vishnevskiy et al., 2017).

MethodologyResearch on digital transformation in asset-intensive industries (Gao et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2013), is still in a nascent phase. For novel and under-researched topics, qualitative research is particularly suitable because it allows the gathering of rich data and answers ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007; Graebner et al., 2012). Thus, we chose a qualitative approach and conducted high-level semi-structured interviews with senior managers at seven leading asset-intensive organisations with operations in Australia—predominantly from the resource sector.

Data collection and analysisIn this research project we focused on the asset-intensive mining industry in Australia. With this focus, we accounted for the huge impact that digital transformation will make in the future to one of Australia's most important industry sectors. Iron ore and coking (or metallurgical) coal, which are considered to be significant inputs into steel commodities, are the main contributors to Australia's total resource exports (Australian Government, 2018), which account for a 10.4% share of the economy (Casey, 2021; Constable, 2020). The Australian resources sector accounts for almost 60% of Australia's exports (Heath, 2019), with iron ore, coal, natural gas, gold, aluminium and petroleum ranking amongst the top ten import and export goods in the country (Australian Government, 2018). The sector is thus of great economic importance for the country.

We interviewed elite informants. Elite informants are particularly interesting sources of data, as these individuals have the ability to strategise and produce changes at an organisational level (Aguinis & Solarino, 2019; Solarino & Aguinis, 2021). Even considering the difficulties in accessing senior managers in such large and complex organisations, we managed to interview seven top executives in Australia. We interviewed executives of asset-intensive organisations in resource sectors due to their size, scope, institutional integration and economic relevance within asset-intensive organisations. The access to elite informants offered a unique opportunity to gain microfoundations in digital strategy and, thus, gain an in-depth understanding of underlying processes, constraints and perceived opportunities regarding the digital transformation of these essential industries (Foss & Pedersen, 2016; Solarino & Aguinis, 2021; Torres de Oliveira et al., 2020). The executive interviews formed our primary data source. All interviews were conducted in the last quarter of 2020. To validate our primary data, we also analysed organisations’ information, media accounts, annual reports and financial information, amongst other secondary data sources, which were triangulated with our primary data (Hussein, 2018).

Following Schultze and Avital (2011), we decided to conduct semi-structured interviews and concentrate on our distinct research topic while also collecting in-depth information (Myers & Newman, 2007). We made use of the advantage of guided interviews, which gave us the opportunity to compare the obtained results because the participants express their opinions on the same general topics. The interviews were conducted by two researchers, one of whom is a senior scholar. The senior scholar has worked closely with C-level executives for years and is very familiar with the resource sector in Australia. This precluded an unequal distribution of power in the interview and guaranteed a conversation on a level playing field (Ostrander, 1993; Solarino & Aguinis, 2021; Welch et al., 2002).

Table 1 provides an overview of the seven interviews that had an average duration of about 70 min. We used purposive sampling to identify elite informants from our professional network who were considered key informants regarding strategic digital transformation in asset-intensive organisations. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed for better analysis. The interviews had two authors present and handwritten notes were taken, which were also analysed. As noted above, in addition to the interviews, we collected secondary data to triangulate and validate our primary data source (Hussein, 2018), such as website information, financial reports, press-release, amongst others. To methodically structure the gathered data and information, we used template analysis (King et al., 2017; Torres de Oliveira et al., 2021) as the main data analysis technique. We selected the computerised analysis software NVivo, which allowed us to analyse the complex and large quantity of collected data and information. The data were analysed by two authors, and multiple interactions occurred until the final coding was agreed upon following an inductive theory-building approach (Eisenhardt, 1989).

Interview sample.

| No. | Title of the individual interviewed | Sector | Duration of the interview in h |

|---|---|---|---|

| I01 | Chief Information Officer | Oil & Gas | 2:20 |

| I02 | Head of Optimisation | Energy | 1:00 |

| I03 | Executive Manager Assets | Energy | 0:51 |

| I04 | Chief Information Officer | Transport | 0:54 |

| I05 | Group Executive Infrastructure Strategy | Health | 1:10 |

| I06 | Subsurface Solutions Manager | Oil & Gas | 1:00 |

| I07 | Manager of Innovation | Mining | 1:00 |

Two authors separately assigned descriptive codes to our interviewees’ statements to gain an understanding of the data's breadth and depth. This first coding round resulted in five broad categories related to digital transformation in asset-intensive organisations that, when refined, resulted in a total of six nodes. Next, the author team had several discussions concerning the identified categories, which led to a second round of categorical coding. Three authors structured and coded the interviews, which led to further coding that considered the theoretical considerations. After consolidating the coding set, we derived nodes in six categories and fourteen subcategories.

In a third coding round, we used axial coding to specify the properties and dimensions of the existing six categories and fourteen subcategories (Corbin & Strauss, 2015). During axial coding, we discussed the intermediate results within the research team and went back to the data to confirm them (Saldaña, 2013). Each workshop was face-to-face and lasted between 51 and 140 min. In these workshops, we reviewed existing codes, discussed ambiguities and reclassified or renamed factors to enhance clarity and meaning. In the last, and final workshop, we continuously reflected on the data and our emerging understanding through memoing and agreed the consensus of six categories and fourteen subcategories (Fig. 1). Further, we used digital transformation-related literature, practitioner studies, and company reports, websites, and other secondary data to triangulate our conceptualisation of the factors of digital transformation in asset-intensive organisations.

FindingsThe context of asset-intensive organisationsAsset-intensive organisations mostly tended to see themselves as laggards in the adoption of digital technologies and digital transformation. Interviewee I05 noted, ‘for a range of different reasons, we've been a little bit late to come to the party with transformation’. The size and length of projects could be substantial; for example, in mining, creating a mine can take up to ten years from discovery to mining the deposit. Thus, the associated investments could also be significant. Organisations could not simply swap out their investments for the latest technology; rather, it must be staged through the life cycle of the company's activities.

Asset-intensive organisations had complex interdependencies through the value chain and within their organisation. They needed to navigate across the cyber–physical spectrum, which made it imperative that they considered system-wide approaches. Modular adoption of digital innovation was not easy due to the tight coupling of business models with physical processes and assets, along with the data elements necessary for system functioning. Hence, as one respondent noted, they are ‘looking at a whole business model as to how we use technology across the whole business’ (I02).

There was a palpable appreciation for the fact that digital innovations could drive business outcomes. As one interviewee noted, there was an ‘increasing reliance on technology to deliver outcomes for the business’ (I04). In our investigation of what was the primary focus of digital transformation efforts, we found an acute focus on improving operational excellence. This was done by using technologies such as the Internet of Things, analytics and information systems to ‘do things more efficiently’ (I03) and ‘using the datasets we have and the information we have and being able to leverage against that and do things in a better way’ (I03). Firms recognised that they were not fully on board with digital transformation yet. Many were still engaged in information-technology-driven modernisation of their processes rather than using digital innovations to fundamentally alter their business models. As interviewee I06 admitted, ‘it's really not a transformation until you're changing the way the business makes decisions’. However, there was wide recognition of the need to leverage digital technologies to be more innovative:

When you are able to ask new questions and make new decisions based on your digital data, until we get to that point where we are literally changing the kind of questions that people can ask to support business decisions, it hasn't really been a transformation. (I06)

Asset-intensive organisations faced a significant uphill battle to change their mindsets to fully adopt digital transformation:

‘Really getting people's head around the fact that you're becoming a digital business and digital is now fundamental to the way things operate’ (I04).

Data as a core assetAsset-intensive organisations clearly recognised the value of mining their data for insights. Technical equipment and devices were omnipresent, and hence data were generated constantly. Some firms had data on systems, projects and equipment that spanned ‘40 years’ worth of legacy data’ (I06). Interviewee I06 noted, ‘We had close to 12 petabytes of mostly seismic data in cloud storage. So, for a time last year, we were Amazon's largest volume data storage customer in the Southern Hemisphere’.

While these firms understood the need to treat data as an asset, much work remained. Most firms continued to struggle with understanding what data they had, what those data could be used for, and how to prioritise the data for analyses. One interviewee noted, ‘We've got all of that backlog of data, and we have to understand all of that right to make the critical decisions that we do’ (I06).

The key challenge faced here was not only the volume of data but the types of data (e.g., image, video, etc.) that needed to be leveraged:

There it's the challenge of the huge volumes of data that they work with right, and these 3D and 4D large, offshore seismic surveys that are literally hundreds of terabytes of data streaming from an offshore vessel directly into a processing centre. (I06)

Concerning the innovation efforts of interviewee I06’s company, they had made great strides in real-time operations and predictive analytics: ‘That was kind of the first area to benefit from things like analytics and machine learning and in AI because it's so close to operational revenue’. Consequently, proven delivered success through their mature practices led to the ability to make further business cases for funding straightforward technologies: ‘If you can reduce downtime on a gas plant the size of the ones we run, that's literally hundreds to thousands of barrels a day. It's very easy to build a use case around that’ (I06).

Digital transformation as a strategyAsset-intensive organisations were seeing the value in building data competence and had started to create dedicated data-science teams:

We are now using the data-science team to do track-wear analysis and look at the effects of various services on the track and also the condition of the track as it changes over time to actually flag the maintenance and the efforts to take place’. (I04).

Not only were companies investing internally in their staff, but they also saw significant value in partnerships: ‘I think it is also investing time in partnerships. Collaboration, right, and investing in that’ (I05). However, unlike previous partnerships, these ones were focused on data and areas where firms were trying to increase their capacities in digital transformation.

Investing in their people to create innovative opportunities had paid off for interviewee I05. By providing data training, their employees could engage with reporting, trending, synthesis and analysis with big data and analytics. This had led the team to make better decisions and productivity improvements through automation: ‘OK, so suddenly we have gained, I think, upwards of probably 30 h of analysis time a week’ (I05).

Organisations were also finding ways to upskill their staff who had some foundational skills and the aptitude to engage in digital projects. It was observed that companies were investing in data literacy and were also creating internal communities of practice to promote the sharing of ideas and knowledge. As participant I01 stated:

We just extended their knowledge, and we created communities of practice, right. But all that guy had to do was just tell people about the stuff he was learning and then point them to resources that were for free because we knew we had a dozen, two dozen people who were interested in bringing up their own python skills.

Some firms had struggled due to the low level of internal capabilities in data science and digital innovation. Their approach was to outsource both data acquisition and processing. Consider the case of a firm that was using drones to monitor the health of its physical assets (e.g., energy storage tanks): ‘we contract both acquisition and processing. That has all been outsourced. So, it's always this handover of data between the acquisition company to the processing company, to the end users of the data who are making the decisions’ (I04).

Observing a global competitor transform, interviewee I01 said that a competitor's chief executive officer ‘decided he wants to be the Spotify of oil and gas and in the process, like stood up this massive data-management data-science team with the express point of being disruptive and ultimately spun off a company, which is a data platform for oil and gas’. Knowing their competitor's focus on data, the executives and staff from interviewee I01’s firm realised investment in data science was needed: ‘They were terrified we were going to be left behind. So, we wanted to do cool things’ (I01).

Lessons learned from initial digital transformation projects, especially those focused on data science, were now being worked on to develop first-mover advantages: ‘So we're taking those lessons learned …and applying it to the very high risk and high uncertainty part of the business getting access to that data quick enough to make decisions before your competitors’ (I06).

Weighing positive and negative impacts of digital transformationAsset-intensive organisations must prioritise safety above all. The operations they engaged in put humans in demanding situations. One company's (interviewee I07) recent key projects were around automation and removing people from dangerous situations. One such example was the use of data to create an autonomous vehicle fleet: ‘In the last two years, the company has observed zero fatalities, which is historical’ (I07).

When it comes to the digital environment, risks from cybersecurity were a major concern. The threat to digital assets from cyber-attacks was recognised across the leadership of these firms: ‘There is [sic] only two kinds of companies on the planet, those [that] have been hacked and those that do not realise they have been hacked’ (I06). Interviewee I04 shared their Board's concerns about cyber-attacks: ‘The Board is very wary of that, particularly denial of service attacks and ransomware attacks’. Investments were being made in this area, such as isolated networks, strong authentication models and capability: ‘We have got a whole group there in the building on a dedicated floor that does nothing but monitor intrusions and do cybersecurity patches and make sure that we are meeting that challenge every day’ (I06). Interview I02 also echoed the cybersecurity threat:

So, on a scale of 1 to 10, it is 12, that is very simple; that is how seriously it is taken. So, we have got dedicated people now just working on cybersecurity. We probably get about 25,000 hits a day that are people trying to crack into the system.

Interviewee I05 mentioned that they were getting over 200,000 hits per day from hackers. The need for security and safety was across the whole organisation: ‘Cybersecurity is a consideration in everything’ (I04). This meant that, at times, innovation was stifled. For instance, companies saw data as an asset but they limited access to it: ‘Previously we viewed it more as being overly protective of that access to it. We were leaving a lot of opportunities on the table’ (I04). COVID-19 impacted operational procedures and access to systems, as interviewee I04 pointed out: ‘We did not do remote access to it. So, we had to revisit this operational technology designed to actually put that in place’. Firms were realising the power of providing access to their data and improving decision-making, in many cases with desensitised data: ‘Obviously, certain data cannot be seen. But obviously, when people understand, and they can use data, then obviously they can start digging and start making better decisions’ (I05). Firms were now attempting to take a balanced approach:

We are trying to actually bring people along and help them to understand that they need to be more cyber aware, and they need to welcome the cyber side of things and hopefully not end up in The Courier-Mail [newspaper]. (I04)

Digital transformation road mapThere was an overwhelming mentality that engineering knowledge was more critical than data-driven insights. Thus, organisations had established a ‘culture of gut decisions’ (I01) and were ‘seeded with mavericks from the get-go’ (I01). The way these firms had hired in the past played a major role, as one interviewee recalled:

It was absolutely overt and explicit and transparent, which is like we are going to be about people, and we are going to hire people because they are experts, and we are going to trust their judgement – it was very ‘Peter Drucker-esque’ in that regard. (I01)

Because many were not university graduates, staff could find the digital transformation more challenging because they viewed automation as a threat and not an opportunity; they were used to working with physical technology and not invisible technology, such as running an oil rig from a remote site using a digital twin. These organisations knew they needed to bring on graduates for the future who would go through a significantly different training program than the incumbents:

So, for example, when I went through, it was six months in the workshop on a broom and work as a tradesman, and six months in the drawing office, learning how not only to draw but also how to manage those files and not allow original drawings out of the office. So, they are the sorts of things that we really need to invest in the future; it is qualified people to take over the roles of us in the future. (I02)

Organisations understandably faced challenges as they sought to link individuals with deep engineering/domain expertise (e.g., mining engineers) with emerging data-science talent. It was necessary to appreciate the nuances of each of these groups in how they experienced data and technologies. The former were digital immigrants who gained experience with information technologies during their professional careers. The latter had not experienced the world without information systems. Moreover, while digital immigrants learned to work with technologies to enhance what they were already doing, while digital natives used technologies to redefine how work should be done. These subtle differences were significant. However, there was recognition that change was needed: ‘We just did not grapple with what digital transformation would mean and what a data-driven culture would mean’ (I01). Firms were reassessing what skills and individuals they needed:

That has [sic] been a challenge for me as a manager. Right. I have had to rethink, you know, what kind of a team I have, [the] kind of people I hire, the kind of service providers I work with, you know, the skill sets that I need to evaluate their performance. (I06)

They were also reviewing what the new workforce would look like:

Huge push to define what a digital engineer looks like in the next decade … what are the skill sets that somebody is going to need to be a digital [engineer]… we are challenging them to pick up the skills they need to move with that job. (I06)

However, there was excitement regarding this change: ‘It is challenging, but it is also pretty damn exciting, you know. So that is why I go and work in the morning’ (I06).

This change will impact these organisations at all levels, from hiring personnel to strategic road-mapping. They were creating technology and data strategy road maps, both in terms of new business models as new processes models, and aligning with the overall corporate strategic road maps:

So, we pulled together a technology strategy and a road map, and it is really aiming to be a 3–5-year road map that we update every six months. (I04)

We are doing a lot of work with revisiting our data strategy road map. You know, we try to pull together for our state-wide infrastructure investment, so we need every single part of our business health-wise to do that. (I05)

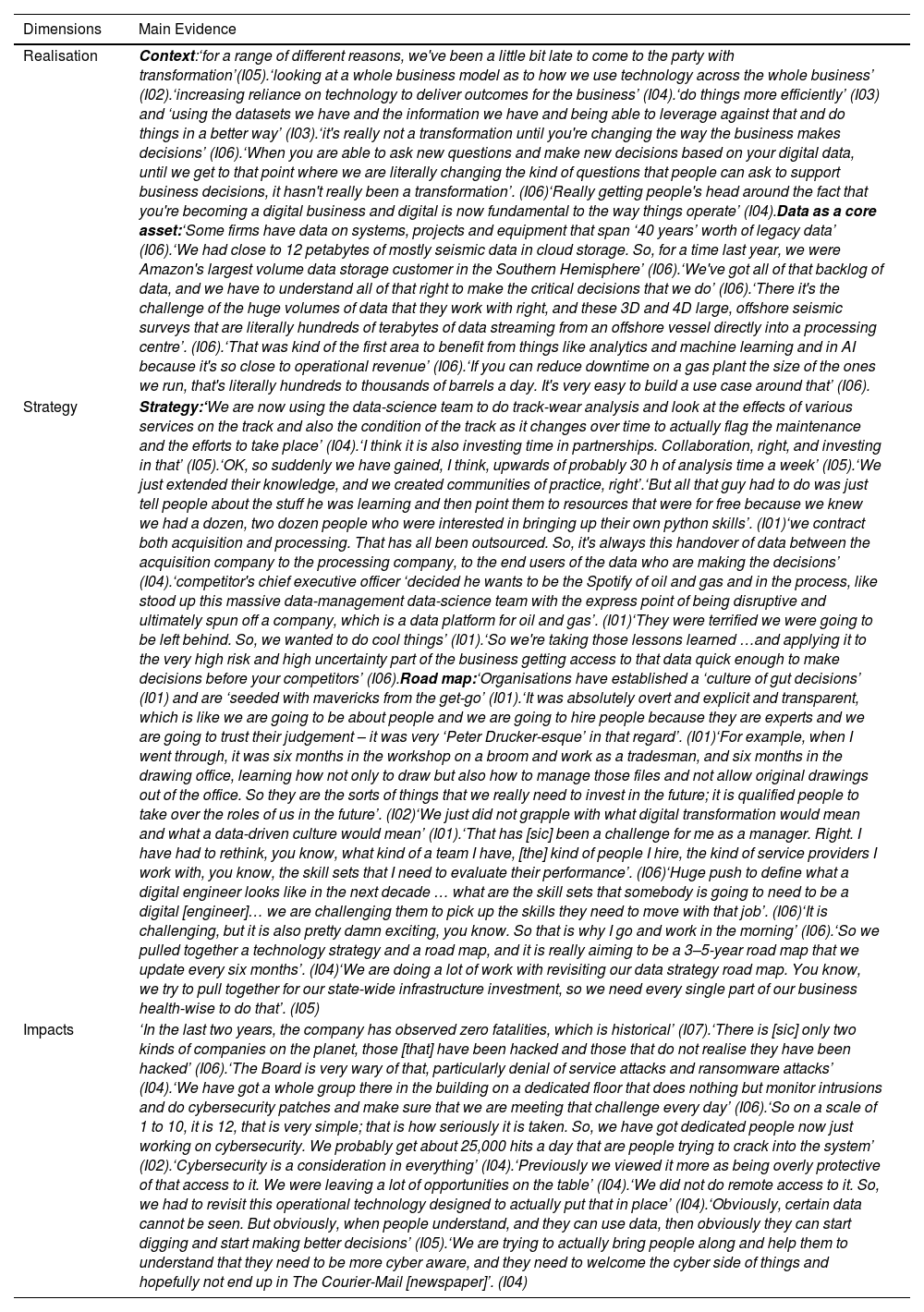

It is important for firms to monitor and adjust their strategic, technology and data road maps, to ensure that they are aligned to meet the changing dynamic environment that digital technologies are creating. Table 2 outlines the interviewees’ main evidence regarding the major dimensions, i.e., realisation, strategy and impacts.

Interviewees’ main evidence on realisation, strategy, and impacts.

| Dimensions | Main Evidence |

|---|---|

| Realisation | Context:‘for a range of different reasons, we've been a little bit late to come to the party with transformation’(I05).‘looking at a whole business model as to how we use technology across the whole business’ (I02).‘increasing reliance on technology to deliver outcomes for the business’ (I04).‘do things more efficiently’ (I03) and ‘using the datasets we have and the information we have and being able to leverage against that and do things in a better way’ (I03).‘it's really not a transformation until you're changing the way the business makes decisions’ (I06).‘When you are able to ask new questions and make new decisions based on your digital data, until we get to that point where we are literally changing the kind of questions that people can ask to support business decisions, it hasn't really been a transformation’. (I06)‘Really getting people's head around the fact that you're becoming a digital business and digital is now fundamental to the way things operate’ (I04).Data as a core asset:‘Some firms have data on systems, projects and equipment that span ‘40 years’ worth of legacy data’ (I06).‘We had close to 12 petabytes of mostly seismic data in cloud storage. So, for a time last year, we were Amazon's largest volume data storage customer in the Southern Hemisphere’ (I06).‘We've got all of that backlog of data, and we have to understand all of that right to make the critical decisions that we do’ (I06).‘There it's the challenge of the huge volumes of data that they work with right, and these 3D and 4D large, offshore seismic surveys that are literally hundreds of terabytes of data streaming from an offshore vessel directly into a processing centre’. (I06).‘That was kind of the first area to benefit from things like analytics and machine learning and in AI because it's so close to operational revenue’ (I06).‘If you can reduce downtime on a gas plant the size of the ones we run, that's literally hundreds to thousands of barrels a day. It's very easy to build a use case around that’ (I06). |

| Strategy | Strategy:‘We are now using the data-science team to do track-wear analysis and look at the effects of various services on the track and also the condition of the track as it changes over time to actually flag the maintenance and the efforts to take place’ (I04).‘I think it is also investing time in partnerships. Collaboration, right, and investing in that’ (I05).‘OK, so suddenly we have gained, I think, upwards of probably 30 h of analysis time a week’ (I05).‘We just extended their knowledge, and we created communities of practice, right’.‘But all that guy had to do was just tell people about the stuff he was learning and then point them to resources that were for free because we knew we had a dozen, two dozen people who were interested in bringing up their own python skills’. (I01)‘we contract both acquisition and processing. That has all been outsourced. So, it's always this handover of data between the acquisition company to the processing company, to the end users of the data who are making the decisions’ (I04).‘competitor's chief executive officer ‘decided he wants to be the Spotify of oil and gas and in the process, like stood up this massive data-management data-science team with the express point of being disruptive and ultimately spun off a company, which is a data platform for oil and gas’. (I01)‘They were terrified we were going to be left behind. So, we wanted to do cool things’ (I01).‘So we're taking those lessons learned …and applying it to the very high risk and high uncertainty part of the business getting access to that data quick enough to make decisions before your competitors’ (I06).Road map:‘Organisations have established a ‘culture of gut decisions’ (I01) and are ‘seeded with mavericks from the get-go’ (I01).‘It was absolutely overt and explicit and transparent, which is like we are going to be about people and we are going to hire people because they are experts and we are going to trust their judgement – it was very ‘Peter Drucker-esque’ in that regard’. (I01)‘For example, when I went through, it was six months in the workshop on a broom and work as a tradesman, and six months in the drawing office, learning how not only to draw but also how to manage those files and not allow original drawings out of the office. So they are the sorts of things that we really need to invest in the future; it is qualified people to take over the roles of us in the future’. (I02)‘We just did not grapple with what digital transformation would mean and what a data-driven culture would mean’ (I01).‘That has [sic] been a challenge for me as a manager. Right. I have had to rethink, you know, what kind of a team I have, [the] kind of people I hire, the kind of service providers I work with, you know, the skill sets that I need to evaluate their performance’. (I06)‘Huge push to define what a digital engineer looks like in the next decade … what are the skill sets that somebody is going to need to be a digital [engineer]… we are challenging them to pick up the skills they need to move with that job’. (I06)‘It is challenging, but it is also pretty damn exciting, you know. So that is why I go and work in the morning’ (I06).‘So we pulled together a technology strategy and a road map, and it is really aiming to be a 3–5-year road map that we update every six months’. (I04)‘We are doing a lot of work with revisiting our data strategy road map. You know, we try to pull together for our state-wide infrastructure investment, so we need every single part of our business health-wise to do that’. (I05) |

| Impacts | ‘In the last two years, the company has observed zero fatalities, which is historical’ (I07).‘There is [sic] only two kinds of companies on the planet, those [that] have been hacked and those that do not realise they have been hacked’ (I06).‘The Board is very wary of that, particularly denial of service attacks and ransomware attacks’ (I04).‘We have got a whole group there in the building on a dedicated floor that does nothing but monitor intrusions and do cybersecurity patches and make sure that we are meeting that challenge every day’ (I06).‘So on a scale of 1 to 10, it is 12, that is very simple; that is how seriously it is taken. So, we have got dedicated people now just working on cybersecurity. We probably get about 25,000 hits a day that are people trying to crack into the system’ (I02).‘Cybersecurity is a consideration in everything’ (I04).‘Previously we viewed it more as being overly protective of that access to it. We were leaving a lot of opportunities on the table’ (I04).‘We did not do remote access to it. So, we had to revisit this operational technology designed to actually put that in place’ (I04).‘Obviously, certain data cannot be seen. But obviously, when people understand, and they can use data, then obviously they can start digging and start making better decisions’ (I05).‘We are trying to actually bring people along and help them to understand that they need to be more cyber aware, and they need to welcome the cyber side of things and hopefully not end up in The Courier-Mail [newspaper]’. (I04) |

From our findings, we developed a dynamic process model of digital transformation, shown in Fig. 2, where we identified not only the mechanisms, triggers and different processes involved but also the dark side of digital transformation—our negative impacts. As our data showed, digital transformation as a strategy was triggered by the digital strategy of a competitor, as well as the need to shield the focal firm against new technology-savvy incumbents that were agile, comfortable and competent in dealing with new technology and data and were not afraid to challenge large, well-established but slow-to-change corporations. Similarly, asset-intensive organisations wanted to shield their firms against large technology companies like IBM, Google and Apple, which—even if large— are known to be agile, to live and breathe new technologies and are highly competent in dealing with large amounts of data. Therefore, asset-intensive organisations saw all those firms as potential disruptors of their business. Competitive advantages in the future—aligned with large amounts of data that they had collected over the years—triggered them to engage in a digital transformation strategy.

However, to create a digital transformation road map, the strategic management literature tells us that firms need to not only understand and validate their internal organisational resources and capabilities but also understand what is available elsewhere (Helfat & Raubitschek, 2018; Sirmon et al., 2011; Teece et al., 1997)—in our case, digital competences and available digital technologies. Organisations are frequently attentive to what happens outside their own internal boundaries and are looking for tools that enhance their process, products and capabilities, amongst others, by following an open innovation strategy (Chesbrough, 2004; Torres de Oliveira et al., 2020). However, this external search for new knowledge, for example, digital technologies to improve internal processes, products, capabilities or others, needs to be aligned not only with the firm's digital transformation strategy to make sense of its implementation (Chanias et al., 2019; Ferreira et al., 2019; C. Matt et al., 2015; Prügl & Spitzley, 2021) but also with the internal resources and capabilities to be captured, assimilated, transformed and exploited into internal routines (He et al., 2022; Helfat & Raubitschek, 2018; Zahra & George, 2002).

Our data showed that, from the digital transformation road map, two important consequences occurred: either asset-intensive organisations developed new business models that were frequently the result of a disruptive change, or they followed a more incremental change through the development of new processes. Both the new business models or new processes models entailed positive and negative aspects. The positive impacts on organisations are well described in the literature (e.g., Vial, 2019; Verhoef et al., 2021; Trittin-Ulbrich et al., 2021), but uncovering the dark side of digital transformation for organisations, especially asset-intensive organisations, has been less studied (H. Trittin-Ulbrich et al., 2021). Our data showed that there were several questions regarding privacy, security, digitised information being misinterpreted or understood incorrectly, or the fact that digitalisation could introduce new bureaucratic dysfunctions that often were the results of an inflexible digital system, which aligned with recent research (H. Trittin-Ulbrich et al., 2021). There were also potential implications in terms of the span of attention from large amounts of information (Simon, 1947) to the fact that new systems might be less efficient or even be the source of a loss of competitive advantage.

Therefore, an important implication of our dynamic process model on asset-intensive organisations is that those corporations need to have in place evaluation systems for their digital transformation. Those evaluation systems will inform the asset-intensive organisations’ overall digital transformation strategy and make sure that it mitigates the negative impacts and enhances the positive ones. The evaluation will further inform digital transformation as a strategy, integrating the dynamic into the process model. Another important implication from our dynamic process model on asset-intensive organisations relates to the identification of the different resources and capabilities needed, and how internal and external logics interact in sourcing or using such resources and capabilities. Finally, uncovering the negative impacts of digital transformation on asset-intensive organisations will allow a firm to create systemic and holistic risk analysis and develop mitigation strategies around those issues.

Implications for theory and practiceTheoretical implicationsOverall, the findings of this research have three main implications. First, we showed that asset-intensive organisations look at digital transformation in a unique way, with the main focus on new business and process models and less concern about new products or services, in contrast to the findings of past literature on non-asset intensive industries (P.C. Verhoef et al., 2021). This is important not only for the strategic management literature in the sense that products and services are not the core reason why digital transformation happens in these firms, as previously suggested (e.g., Ferreira et al., 2019; Li, 2020; Rachinger et al., 2018; Verhoef et al., 2021), but also for the information systems literature where digital transformation is associated with technology implementation towards new opportunities for service engagement (e.g., Bharadwaj et al., 2013; Matt et al., 2015; Vial, 2019).

Second, we talked to the theoretical tension between the role of context in researching corporate behaviour (e.g., Autio et al., 2014) and organisational identity (e. g., Kammerlander et al., 2018) during transformative processes. This tension and the organisation types that we studied allowed us to uncover new dimensions of the dark side of digital transformation as well as bring the discussion to a firm level. Previous debate about the dark side of digitalisation or digital transformation has focused on societal or political implications, with the classic example that digitalisation has allowed the growth of extremely large firms (e.g., Amazon, Apple and Google) that may control larger resources than countries, with implications at several levels (for a discussion on this topic, please refer to Trittin-Ulbrich et al., 2021). Our research brings this dark side of digitalisation to a firm level, and specifically to the risks that digital transformation entails. This discussion complements previous work that has started to uncover the negative aspects of digital transformation at the firm level (e.g., Davenport & Westermann, 2018; Shahi & Sinha, 2021) but goes further to expose new dimensions.

Finally, our results allowed us to establish a dynamic process model of digital transformation for asset-intensive organisations. Our dynamic process model complements more generalist process models, such as those by Verhoef et al. (2021), Vial (2019) and Heavin and Power (2018), by not only establishing the mechanisms in place between the different processes but also by showing the different triggers that activate the movement from one stage to the next. This adds to our current knowledge on digital transformation seen from a rather conceptual and static model perspective.

Implications for practiceOur research presents several implications for practice, which are even more important due to the unique prerequisites of asset-intensive organisations and their special significance for economies. First, we explained why asset-intensive organisations are, and should be cautious, when engaging in digital transformation. We uncovered some of the potentially negative aspects that such transformation entails, which we named the ‘dark side of digital transformation’, and therefore we call to managers to be attentive to those and other potentially negative aspects and their impacts. Managers can also create risk assessments and systematic monitoring around those negative aspects but, more importantly, they can also create mitigation strategies to prevent the escalation of those negative impacts.

Second, we explained why asset-intensive organisations are slow in engaging in digital transformation and the adoption of Industry 4.0. This is particularly important for asset-intensive organisation suppliers and clients because those suppliers or clients might be much more eager to introduce digital solutions to enhance the processes between them and the asset-intensive organisation. Such clients and suppliers need to understand that asset-intensive firms are much less agile to reverse decisions, and, therefore, the appetite of asset-intensive firms for disruptive systems is at a much higher level when looking at a risk analysis scale. In stable and slow industries, where asset-intensive organisations sit, there may be competitors, current and incumbent, that push for a quick digital transformation because highly technological firms are entering into their territories; however, our research suggests that there is potentially much to lose, and quick wins could jeopardise long-term competitive advantages. Our research showed that managers of such asset-intensive organisations should be upfront with their stakeholders about why digital transformation for their organization might follow a different path than other firms, by showing the potential negative impacts of such transformation.

Finally, our results point to a focus on new processes and business models rather than on new products or services. While this fosters the long-term perspective of the digital transformation of asset-intensive organisations, digital suppliers can use these results to focus their research and development endeavours towards those new business models instead of trying to enhance the large-asset firm's products or services. Thus, for example, new market entrants can focus on the vast amounts of data that asset-intensive organisations have stored and gathered from every single process and transaction and use that data to improve the asset-intensive firm's processes. Alternatively, managers of asset-intensive organisations can look at the positive outcomes of digital transformation that we uncovered and try to enhance them either internally or through externally-sourced agents that can help with such transformation.

Limitations and future researchDue to the research method and design used, this study is subject to several limitations. First, the research team chose a qualitative research design due to the theoretical problem at hand. While this provided partial insights into the companies studied, the research approach limits the generalisability of the findings. Second, generalisability is further limited by the choice to focus on asset-intensive organisations. While the study provides a broad insight into asset-intensive organisations and we claim high generalisability of the results for companies with similar conditions, a transfer of the results to other industries and organisational forms has to be critically questioned. Third, the restriction to interviewees who could be categorised as elite informants represents a further limitation. While the authors deliberately focused on elite informants to achieve a strategically relevant and meaningful perspective on the digital transformation of asset-intensive organisations, this approach did not cover all perceptions of a company, and the phenomenon may be perceived differently by different stakeholders.

Our research offers several avenues for future research. First, it will be important to build on our understanding of digital transformation in asset-intensive organisations with more in-depth cases studies (to gain a more nuanced picture of the process dynamics) and quantitative methods in the industry (to be able to arrive at industry-wide insights). Second, critical to an asset-intensive firm's success with digital transformation and to innovate business models is the firm's ability to be ambidextrous. While the literature is replete with studies on organisational ambidexterity, many of these studies do not account for the nuances faced by asset-intensive organisations. Third, as discussed, digital technologies offer asset-intensive organisations innovative solutions to advance their health and safety objectives. Yet, their uptake of these technologies is often slow because of these very concerns. Put differently, the unproven nature of technology affordances from a performance viewpoint often impedes their adoption. Research is needed on how asset-intensive firms can balance the risk and opportunities that arise with digital technologies to increase their rate of adoption. Fourth, asset-intensive organisations have a long way to go when it comes to upskilling their workforce to be ready to take advantage of the current digital revolution. Research is desperately needed to help these firms understand how to upskill their existing workforces and attract the next-generation digital talent who often do not view these industries as their primary choice for work. Finally, given the rising pressure faced by asset-intensive organisations when it comes to their environmental and social responsibilities, it is vital that digital innovations be leveraged to drive revisions to existing operational and business models. To do so, firms will need to understand how to embed digital technologies to drive innovations that lower (or even eliminate) environmental harm and increase the net positive these firms contribute to our society (Ajwani-Ramchandani et al., 2021).

Christoph Buck (christoph.buck@qut.edu.au) is a department head of the Fraunhofer Project Group Business and Information Systems Engineering (Germany) and an Adjunct Associate Professor at the Queensland University of Technology (Australia). He holds a PhD in Information Systems from the University of Bayreuth. He has led numerous transformation projects with asset-intensive incumbents in the areas of digitalization and innovation. His research interests include business model innovation, digital transformation, innovation systems, and information privacy and security.

John Clarke (johnwclarke@hotmail.com) is a recent graduate from the Queensland University of Technology, having completed an Executive MBA that included research on digital transformation in the heavy industries sector. His undergraduate degree in computing was also obtained from the Queensland University of Technology. He is a widely experienced technology leader with a substantial career in both corporate leadership and consultancy roles, across a variety of industry sectors around the world. He has a strong commitment to the successful delivery of transformation programs and continuous improvement initiatives as well as the development and implementation of innovative new customer-facing products. He is acknowledged by industry peers with innovation awards that recognise achievements, including creating digital banking products to help domestic violence victims, developing a new voice-operated customer banking service that utilises AI to perform everyday banking transactions, and the creation of a digital awards system for customers.

Rui Torres de Oliveira (rui.torresdeoliveira@qut.edu.au) is an Associate Professor at the School of Management at the QUT Business School. His work has been published in journals as: Journal of World Business, Global Strategic Journal, Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, Journal of Business Research, Small Business Economics, Journal of Cleaner Production, Resources, Conservation & Recycling Journal, Social Indicator Research, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, International Journal of Emerging Markets, amongst others. Rui holds a Master's degree in Civil Engineering, an MBA, and a Doctorate on International Business and Strategy from Manchester Business School in the UK.

Kevin C. Desouza (kevin.desouza@qut.edu.au) is a Professor of Business, Technology and Strategy at the School of Management at the QUT Business School. He is a Nonresident Senior Fellow in the Governance Studies Program at the Brookings Institution. He has held tenured faculty appointments at the University of Washington, Virginia Tech, and Arizona State University. Desouza has authored, co-authored, and/or edited nine books. He has also published more than 130 articles in journals across various disciplines, including information systems, information science, public administration, political science, technology management, and urban affairs. Desouza has received more than $2 million in research funding from both private and government organizations.

Parisa Maroufkhani (parisa.maroufkhani@usherbrooke.ca) is an associate researcher at IntelliLab.org à l’École de gestion de l'Université de Sherbrooke. She has earned her PhD degree from Universiti Teknologi Malaysia in information system management. Her PhD thesis mainly was on the way Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) could take advantage of big data analytics adoption. She has published in variety of journals including International Journal of Information Management. Parisa's research interest lied in evolving technologies, such as big data analytics, and blockchain. Her interest is to find out how organizations, in particular SMEs and start-ups can create business values from the adoption of emerging technologies.