Editado por: Abbas Mardari

Última actualización: Julio 2022

Más datosThe original intention of the government was to provide financial subsidies to firms by implementing innovation support policies. In turn, this will encourage these firms to carry out technological innovation activities. However, there are still differing views in the academic community on whether government subsidies have a stimulating effect or a crowding-out effect on enterprise innovation. The theoretical and empirical research conclusions are uncertain. In this study, samples unlisted companies in the Shanghai and Shenzhen A-share markets in China from 2012 to 2020. The entrepreneurial spirit is the entry point to empirically testing the impact of government subsidies on enterprise innovation under financial constraints. The research results show how government subsidies have a significant stimulating impact on enterprise technological innovation activities. More subsidies don't necessarily mean better results because research shows an inverted U-shape. Entrepreneurial spirit plays a significant moderating role in transmitting and optimizing the driving effect of government subsidies. Further heterogeneity analysis shows that government subsidies and entrepreneurial spirit have different driving and moderating effects on the innovation of enterprises with differing natures and scales depending on the region. From a regional perspective, eastern enterprises are better suited in optimizing government subsidies to stimulate enterprise innovation. From the perspective of enterprise nature, private enterprises are more motivated and better able to optimize government subsidies than state-owned enterprises. Regarding enterprise scale, small and medium-sized enterprises can more efficiently optimize government subsidies to stimulate enterprise innovation than large enterprises. The contribution of this paper is to expand the understanding of the impact of government subsidies on enterprise innovation activities.

Over the decades, technological innovation has become an important factor in driving economic growth (Steenhuis & Bruijn, 2012). As a microcosm of the economy and society, enterprises play a crucial role in the development process of technological innovation (Egbetokun, 2015). Especially in an era of economic globalization and digitalization, innovation has become a key for an enterprise's survival and development. By continuous innovation, enterprises can adapt to market changes and customer needs, and enhance their competitiveness and profitability (Daksa et al., 2018). However, the process of innovation is both challenging and risky. Even after investing large amounts of resources, enterprises still face uncertainties in technology and the market (Brouwer et al., 1993; Radas et al., 2015). This increases the operating and sunk costs of enterprises and may lead to bankruptcy (Petrin, 2018; Zacca & Alhoqail, 2021). Therefore, government subsidy policies are crucial for enterprise innovation.

Government subsidies can help enterprises reduce costs, improve efficiency, and encourage innovation (Zúñiga-Vicente et al., 2014). At the same time, government subsidy policies can promote cooperation and knowledge sharing among enterprises and drive innovation of the entire industry (Ostapenko, 2016 ). Under this concept, governments around the world have formulated support policies to stimulate enterprise innovation and the technological progress (Sun et al., 2020). Examples include the Small Business Innovation Research Program in the United States, the Industrial Research Assistance Program in Canada, the Zentrales Innovations Program Mittelstand in Germany, the Tech Incubator Program for Startup in South Korea, and the Productivity Solutions Grant in Singapore. The implementation of these policies aims at reducing costs, improving efficiency, and providing a good environment for enterprise innovation.

The Chinese government has taken a series of measures to support enterprise innovation, such as the National Key R&D Program, the Innovation Fund of the Ministry of Science and Technology, and the identification of high-tech enterprises. However, there are challenges in implementing these government subsidy policies. For example, the government subsidies may be used ineffectively which might lead to waste and overspending (Yu et al., 2016). The policies may distort the market, affect fair competition among enterprises, and even lead to the situation of "government choosing winners" (Lichtenberg, 1987; Chen, 2022). Academic research has called into question the relationship between government subsidies and innovation. There are three types of relationships between government subsidies and innovation as identified by existing research:

- 1)

A complementary relationship where government subsidies can promote innovation, encourage firms to invest more actively in activities, and thereby improving the efficiency of the process (Becker,2015; Chen et al., 2020).

- 2)

A negative or crowding-out relationship is a situation where government subsidies may hurt innovation by causing firms to reduce their investment or transfer resources to other areas (Irwin & Klenow, 1996; David, 2000; Acemoglu et al., 2013).

- 3)

The relationship is based on a U-shaped, inverted U-shaped, or S-shaped relationship between the complementary and crowding-out effects (Dai & Cheng, 2015; Huang, 2016).

Multiple factors must be taken into consideration of the complex relationship between government subsidies and firm innovation. While scholars have analyzed the impact of government subsidies on financial constraints (Howell, 2015), environmental regulations (Zhao & Sun, 2016), and corruption, it is essential not to overlook the role of the entrepreneurial spirit on these activities. As a necessary agent who drives innovation and guides activities into the market, the use of entrepreneurial spirit may be the key to promoting firm innovation, bridging financial constraints, and rationalizing the allocation of production factors (Erken et al., 2018). The perspective of the entrepreneurial spirit on the effect of government subsidies on firm innovation has yet to be fully explored.

The goal of this report is to answer the three main questions: What impact do government subsidies have on enterprise innovation? What role does the entrepreneurial spirit play in the process of government subsidizing enterprise innovation? Does entrepreneurial spirit improve the efficiency of enterprise innovation resource allocation?

Our contributions to this study are threefold. First, we explore the relationship between government subsidies and firm innovation from the perspective of the entrepreneurial spirit. This expands the research perspective on government subsidies and helps us better understand how it affects firm innovation activities. Second, we consider the financial constraints of firms, which leads to a better understanding of the ability of the entrepreneurial spirit to allocate innovation resources. Third, we investigate the impact of government subsidies on firm innovation from the perspectives of firm size, ownership, and economic differences, which is significant for understanding the actual effects of these subsidies.

Literature review and hypothesesEnterprise innovation, capital constraints and government subsidiesThe innovation activities of enterprises require a continuous investment of resources due to long cycles, high inputs, and high risks. (Hottenrott & Czarnitzki, 2011). Although under the constraints of interests and risks, these activities may easily fall into the dilemma of "underinvestment" (Bottazzi et al., 2014; Hu, 2019).

In addition, technological progress stems from knowledge spillovers, but knowledge has the non-competitive and partially exclusive characteristics of a public good. This may lead to the expected return on external investment being lower than socially optimal (Nelson, 1959; Huggins & Thompson, 2015). Therefore, the "incomplete fit" allocation characteristic of enterprise innovation resources determines the underinvestment of external investment (Hall & Lerner, 2010; Xu et al., 2019).

Simultaneously due to factors of information asymmetry and limited financial channels, innovative enterprises often cannot generate sufficient external investment, resulting in market failure. (Davis, 2001; Cincera & Ravet, 2010). Government subsidies have become an important means of remedying the situation.

Hall et al. (2016) found that funding constraints restrict enterprise R&D investment based on data from major European countries and harm enterprise innovation output as well. Government subsidies for enterprise innovation are an important measure to solve the issue of insufficient R&D investment driven by profits and to compensate for market failure.

On one hand, existing research shows that government subsidies supporting enterprise innovation increase funds, reduce costs, and alleviate business risks related to enterprise innovation (Hewitt-Dundas & Roper, 2010). On the other hand, by reducing costs, they increase the expected return on private investment and compensate for the impact of external investment (Ahn et al., 2020).

Görg and Strobl (2007) used UK enterprise data to find that direct subsidies on the fiscal side significantly increased private R&D investment with a complementary effect. Szücs (2020) found that subsidies from the European Union's Framework Programme for Research and Innovation (EU FP) significantly increased enterprise R&D output. Without other variables, it can be concluded that short-term government subsidies can reduce funding constraints and promote enterprise innovation. Based on the above analysis, we propose a hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1

Financial constraints inhibit the innovation activities of enterprises, while government subsidies make up for the lack of internal input and financing constraints to a certain extent and promote the innovation activities of enterprises.

Entrepreneurship and allocation of innovation resourcesThe core characteristics of entrepreneurship include the attributes of risk-taking, innovation awareness, and a broad vision (Gartner, 1988; Hayton & Kelley, 2006). It inspires entrepreneurs to have a keen perception of market opportunities (Marvel & Lumpkin, 2007) by converting new expertise into the knowledge economy and promoting continuous innovation of enterprises (Nelson, 1959; Politis & Gabrielsson, 2009).

Schumpeter (1934) pointed out that innovation depends on the "creative destruction" of entrepreneurs. Thus, entrepreneurship is crucial to promoting business innovation. In defining entrepreneurship, Schumpeter believed that it is the ability to reorganize production factors promptly through new processes, products, channels, raw materials, and to promote the effective operation of various production factors.

While Knight (1921), Drucker and Noel (1986), and others argue, entrepreneurship is the ability to take entrepreneurial risks and undertake risks. Therefore, entrepreneurship is not only a factor in promoting the development of enterprise innovation activities but should also be used as a guiding mechanism, coordinate resource constraints and government subsidies, and promote enterprise innovation (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996).

The important impact of entrepreneurship is on the timely adjustment of production factors through government subsidies and resource constraints. First, entrepreneurship enhances the incentive effect of government subsidies on enterprise innovation. The innovation bias of entrepreneurs is goal oriented. Under the guidance of innovation goals, the incentive effect of government subsidies is continuously magnified by the innovation bias of entrepreneurs (Vuuren & Alemayehu, 2018).

Second, entrepreneurship helps to reduce the effect of resource limitations (Wiklund & Shepherd, 2005). The market decision-making and risk-taking abilities of entrepreneurs enable them to purposefully mobilize information, ideas, knowledge, capital, integrate scarce resources, innovate production systems, and other factors (Rosenbusch et al., 2013).

Third, entrepreneurship allows flexibly in allocating resources under resource constraints (Madrid-Guijarro et al., 2009) and maximizing the utility of limited resources (Eggers et al., 2013). Based on the meta-analysis, Stam et al. (2014) found, that the moderating effect of entrepreneurship can increase the innovation performance of small and medium-sized enterprises. According to the above analysis, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2

Entrepreneurship moderates enterprise innovation activities, enhances the incentive effect of government subsidies on enterprise innovation, and reduces financial constraints.

Heterogeneity of firm innovationThe same regulatory mechanism for government subsidies and financial constraints affect entrepreneurship as well (Crudu, 2019; Srikanth & Maram, 2020). From the viewpoint of government funding, the supplemental effect of subsidies on enterprise innovation funds are unable to fundamentally improve the innovation ability of enterprises.

Because of the time limits of government subsidy policies, this requires enterprises to rely on internal driving factors of enterprises and less on government support for their innovation activities (Sanchaniya et al., 2021). However, the regulatory effect of entrepreneurship modifies the timeliness of government subsidies. This reduces the soft and hard constraints in the innovation process of enterprises through the internalization of external funds (Carboni, 2017) and stimulates the occurrence of enterprise innovation activities.

Concurrently, the internalization of external funds makes the impact of government subsidies on enterprise innovation independent of their cyclicity and timeliness (Ren, 2022). Therefore, entrepreneurship has a regulatory effect on government subsidies. But due to the different innovation environments and marketization levels of various enterprises, the regulatory effect of entrepreneurship varies as well.

Bosma et al.(2018) believe that the regulatory, cognitive, and normative dimensions of the institutional environment have the most significant impact on the entrepreneurial spirit. In addition, different property rights (Ahn & Mortara, 2020), and business scales have a regulatory effect on resources. Entrepreneurship has a moderating effect on government subsidies and financial constraints, but the effects vary based on business backgrounds, property rights, and sizes. Based on the above analysis, a hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 3a

Private entrepreneurship plays a greater role in regulating government subsidies and financial constraints than state-owned enterprises.

Hypothesis 3b

The entrepreneurial spirit has a greater regulatory effect on government subsidies and financial constraints in economically developed areas than their underdeveloped counterparts.

Hypothesis 3c

Small-scale entrepreneurship has a greater regulatory effect on government subsidies and financial constraints than large enterprises.

Data and methodDataThe research sample data for the A-share listed companies in the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock markets from 2012 to 2020 was derived from the Guotai-an (CSMAR) and Wind financial databases. To obtain representative and reliable research results, we screened the preliminary samples.

First, we obtained 31,144 valid sample companies by excluding financial, real estate, risk warning companies, and companies with significant missing data. Second, we implemented a two-tailed 1% exclusion method for all continuous variables. This method controlled the abnormal impact of extreme values by excluding observations in the upper and lower 1%. Finally, the key variables calculated in this study, such as Tobin's Q value, financial constraint indicators, and Concentration Ratio, were obtained from the annual reports of the listed companies.

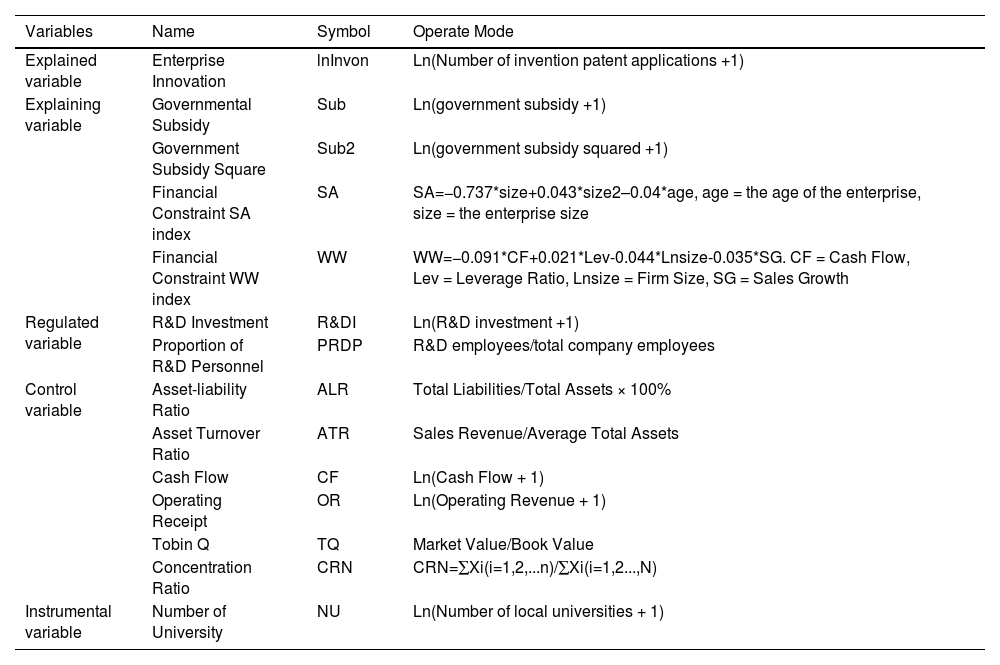

VariableExplained variable: corporate innovation. This study used the natural logarithm of the year-end number of patent applications (Ln(number of invention patent applications + 1)) of Lin et al. (2021) and Tan et al. (2020) to measure corporate innovation strength.

The number of patent applications can objectively reflect the output of corporate innovation activities. In addition, we also use the natural logarithm of the lagged one period of the year-end number of patent applications as a robustness check on the research conclusions. Please refer to the beginning of Table 1 for specific details.

Variable description.

| Variables | Name | Symbol | Operate Mode |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explained variable | Enterprise Innovation | lnInvon | Ln(Number of invention patent applications +1) |

| Explaining variable | Governmental Subsidy | Sub | Ln(government subsidy +1) |

| Government Subsidy Square | Sub2 | Ln(government subsidy squared +1) | |

| Financial Constraint SA index | SA | SA=−0.737*size+0.043*size2–0.04*age, age = the age of the enterprise, size = the enterprise size | |

| Financial Constraint WW index | WW | WW=−0.091*CF+0.021*Lev-0.044*Lnsize-0.035*SG. CF = Cash Flow, Lev = Leverage Ratio, Lnsize = Firm Size, SG = Sales Growth | |

| Regulated variable | R&D Investment | R&DI | Ln(R&D investment +1) |

| Proportion of R&D Personnel | PRDP | R&D employees/total company employees | |

| Control variable | Asset-liability Ratio | ALR | Total Liabilities/Total Assets × 100% |

| Asset Turnover Ratio | ATR | Sales Revenue/Average Total Assets | |

| Cash Flow | CF | Ln(Cash Flow + 1) | |

| Operating Receipt | OR | Ln(Operating Revenue + 1) | |

| Tobin Q | TQ | Market Value/Book Value | |

| Concentration Ratio | CRN | CRN=∑Xi(i=1,2,...n)/∑Xi(i=1,2...,N) | |

| Instrumental variable | Number of University | NU | Ln(Number of local universities + 1) |

Explanatory variable: Government subsidies. Following the approach of Boeing (2016), this study used the natural logarithm of the number of government subsidies received by enterprises in the current period as the measurement standard. Please refer to the second and third rows of Table 1 for specific details.

Government subsidies include tax refunds, direct subsidies, and loan interest subsidies, among other forms. Relevant government subsidy information is disclosed in the financial statements of enterprises each year, and this public data is collected to construct the government subsidy variable. The logarithmic transformation of the amount of government subsidies can alleviate the influence of extreme values and obtain more robust regression results.

Explanatory variable: Financial constraints. Financing includes internal and external financing, and the idea of measuring financial constraints stems from the difference between the cost of both these methods. Common methods for measuring financial constraints include the KZ, WW, SA, and ASCL indexes. The KZ index uses an ordered Logit method to regress on the cash holdings, asset-liability situation, and Tobin's Q of enterprises, and constructs the KZ index based on the regression parameters.

The larger the index, the higher the level of financial constraints faced by the enterprise (Kaplan & Zingales, 1997). While used to calculate the KZ index, the Tobin's Q value has a serious measurement bias (Erickson & Whited, 2000). This leads to deviations in the KZ index results. Therefore, Whited & Wu (2006) proposed the WW index usin6g the generalized method of moments (GMM) based on factors such as asset-liability ratio, cash flow, enterprise size, and enterprise growth rate. However, the variables used to calculate the WW index have endogeneity characteristics.

To avoid this interference, Hadlock and Pierce (2010) proposed the SA index using quantitative data on enterprise financial constraints and an ordered Logit model. In addition, Mulier et al. (2016) constructed the ASCL index based on investment-cash flow sensitivity using factors such as the establishment years of European small and medium-sized enterprises, the asset-liability ratio, and debt-paying ability. As a result, this study intends to use the SA index to measure the financial constraints of enterprises for the benchmark regression and the WW index for robustness testing. These specific calculation methods are in the fourth and fifth rows of Table 1.

Moderating variable: Entrepreneurial spirit. We use the natural logarithm of R&D investment as a proxy for entrepreneurial spirit. R&D investment reflects the vision and determination of entrepreneurs in technological innovation. As a result, this can affect their perception and utilization of government subsidy resources.

To test the robustness of the empirical data, the proportion of R&D personnel was used as another proxy variable for entrepreneurial spirit. The number of R&D personnel reflects the investment of enterprises in technological innovation and are likewise important indicators for characterizing entrepreneurial innovation attitudes. Please refer to the sixth and seventh rows of Table 1 for specific details.

Control variables: Adopting the research methods of Zhou et al. (2017) and Wu et al. (2020), this study uses financial data of listed companies as control variables. First, the asset-liability ratio reflects the asset structure and operating conditions of the enterprise. Second, the cash flow status indicates the financial pressure of the enterprise. Third, the asset turnover ratio signals the flow rate between asset inputs and outputs of the enterprise. Fourth, the operating income return indicates the status of the enterprise. Fifth, Tobin's Q value reflects the actual value of listed companies. Last, industry concentration controls the industry characteristics of listed companies. The specific calculation methods are detailed in the eighth to fourteenth rows of Table 1.

MethodTo test the impact of government subsidies on enterprise innovation under financial constraints, we adopt the stepwise regression method to construct the following model:

Each of the symbols are defined below: Innov: corporate innovation. I: the individual listed company. t: denotes time. Sub: the logarithm of the number of government grants obtained from the sample data. FC: is the index of financing constraints measured from the listed company data Control: denotes gearing ratio, cash flow situation, return on total assets, company size, Tobin's Q value, industry concentration, and etc. α : the parameter of estimation. ε: random error term.

To test hypothesis 2, this paper takes entrepreneurship as a moderating variable and builds the following model:

Where ET represents entrepreneurship, the moderating effect of entrepreneurial innovation spirit on financial constraints and government subsidies by generating interaction terms between entrepreneurship, financial constraints, and government subsidies, using entrepreneurship as the moderating variable.

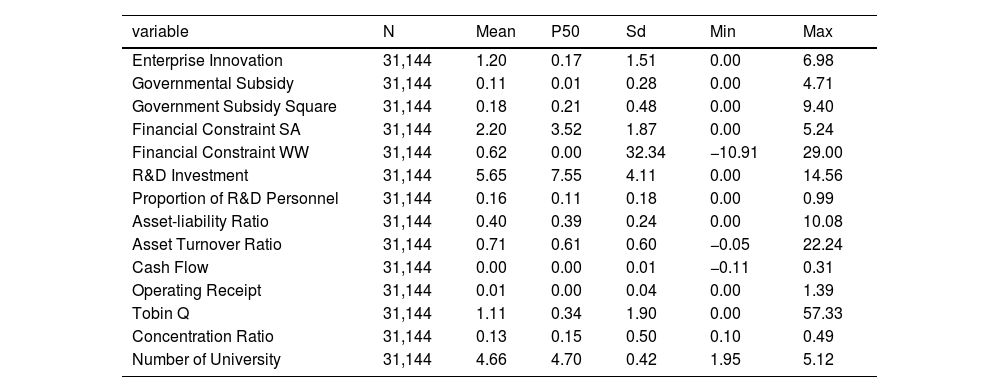

Descriptive statisticsTable 2 reports the descriptive statistical results of the research variables. In Table 2 below, the explained variable and enterprise innovation show significant differences with a mean, median, and standard deviation of 1.2, 0.17, and 1.51, respectively. This indicates that the level of innovation among enterprises as well as the performance of each enterprise are significantly different. While the independent variables, the mean, median, and standard deviation of R&D investment were 5.65, 7.55, and 4.11, respectively.

Descriptive statistics.

| variable | N | Mean | P50 | Sd | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterprise Innovation | 31,144 | 1.20 | 0.17 | 1.51 | 0.00 | 6.98 |

| Governmental Subsidy | 31,144 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 4.71 |

| Government Subsidy Square | 31,144 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 9.40 |

| Financial Constraint SA | 31,144 | 2.20 | 3.52 | 1.87 | 0.00 | 5.24 |

| Financial Constraint WW | 31,144 | 0.62 | 0.00 | 32.34 | −10.91 | 29.00 |

| R&D Investment | 31,144 | 5.65 | 7.55 | 4.11 | 0.00 | 14.56 |

| Proportion of R&D Personnel | 31,144 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.99 |

| Asset-liability Ratio | 31,144 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 10.08 |

| Asset Turnover Ratio | 31,144 | 0.71 | 0.61 | 0.60 | −0.05 | 22.24 |

| Cash Flow | 31,144 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.11 | 0.31 |

| Operating Receipt | 31,144 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 1.39 |

| Tobin Q | 31,144 | 1.11 | 0.34 | 1.90 | 0.00 | 57.33 |

| Concentration Ratio | 31,144 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.49 |

| Number of University | 31,144 | 4.66 | 4.70 | 0.42 | 1.95 | 5.12 |

This reflects the differences in R&D investment among enterprises. Most enterprises have a low to medium level of R&D investment. The mean values of the financial constraint SA index and WW index are 0.18 and 2.2, respectively. Most enterprises face varying degrees of financial constraints with some having lower and others higher financial constraints. The mean and standard deviation of government subsidies were 0.11 and 0.28, respectively. This indicates significant differences in the level of subsidy for enterprises. The amount of government subsidies enterprises receive may be related to factors such as enterprise size, industry, and region.

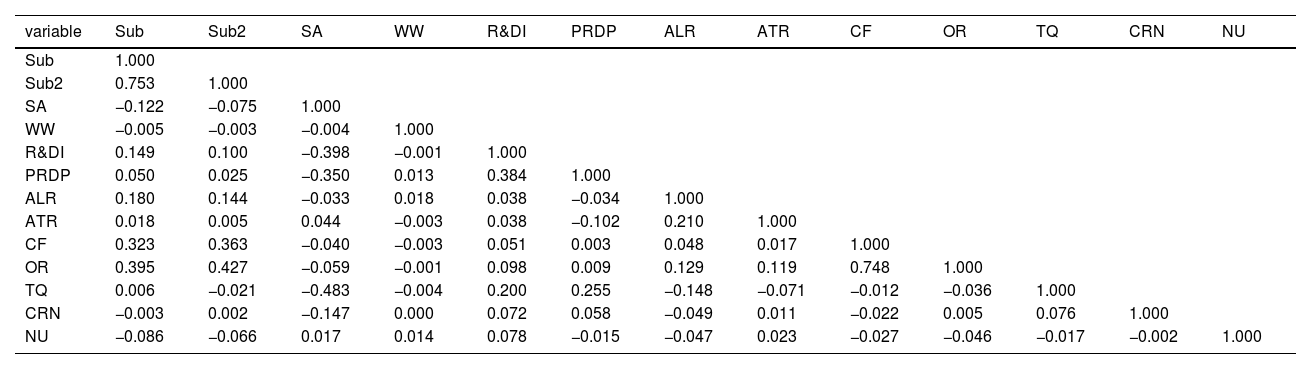

To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the regression analysis, this study examined the correlation between all independent variables. Table 3 reports the results of the Pearson correlation coefficient test. The test showed the absolute value of the correlation coefficient between all independent variables was less than 0.8 which indicates the absence of multicollinearity.

Correlation test.

| variable | Sub | Sub2 | SA | WW | R&DI | PRDP | ALR | ATR | CF | OR | TQ | CRN | NU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| Sub2 | 0.753 | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| SA | −0.122 | −0.075 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| WW | −0.005 | −0.003 | −0.004 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| R&DI | 0.149 | 0.100 | −0.398 | −0.001 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| PRDP | 0.050 | 0.025 | −0.350 | 0.013 | 0.384 | 1.000 | |||||||

| ALR | 0.180 | 0.144 | −0.033 | 0.018 | 0.038 | −0.034 | 1.000 | ||||||

| ATR | 0.018 | 0.005 | 0.044 | −0.003 | 0.038 | −0.102 | 0.210 | 1.000 | |||||

| CF | 0.323 | 0.363 | −0.040 | −0.003 | 0.051 | 0.003 | 0.048 | 0.017 | 1.000 | ||||

| OR | 0.395 | 0.427 | −0.059 | −0.001 | 0.098 | 0.009 | 0.129 | 0.119 | 0.748 | 1.000 | |||

| TQ | 0.006 | −0.021 | −0.483 | −0.004 | 0.200 | 0.255 | −0.148 | −0.071 | −0.012 | −0.036 | 1.000 | ||

| CRN | −0.003 | 0.002 | −0.147 | 0.000 | 0.072 | 0.058 | −0.049 | 0.011 | −0.022 | 0.005 | 0.076 | 1.000 | |

| NU | −0.086 | −0.066 | 0.017 | 0.014 | 0.078 | −0.015 | −0.047 | 0.023 | −0.027 | −0.046 | −0.017 | −0.002 | 1.000 |

The correlation coefficient test results also showed a positive correlation between entrepreneurial spirit and government subsidies with enterprise innovation. This indicates that enterprises with both stronger entrepreneurial spirit and higher government subsidies led to more active innovation activities and outputs.

In contrast, financial constraints were negatively correlated with enterprise innovation. High levels of financial constraints led to lower levels of enterprise innovation. Therefore, factors, such as entrepreneurial spirit, government subsidies, and financial constraints, have an important impact on enterprise innovation.

They can enhance or inhibit the intention and implementation of innovation activities in enterprises. As a result, it can affect the innovation performance of enterprises. This finding provides preliminary evidence for further empirical testing of the conclusion that these three variables have an impact on enterprise innovation.

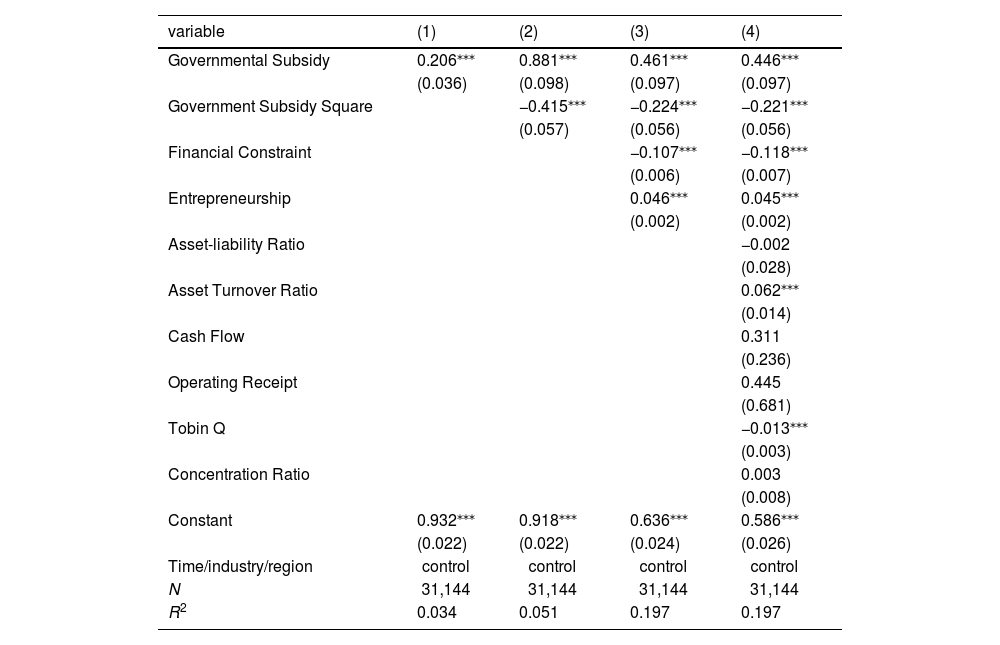

Empirical analysisBaseline regressionAs panel data of listed companies with a lengthy research period were used for this study, a Hausman test was conducted before establishing the regression model for empirical analysis. This was to determine whether the fixed effects model or random effects model was more suitable for the data characteristics and theoretical hypotheses to be verified.

The results of the Hausman test showed that the chi-square value was significant at the 1% level. This indicated that the fixed effects model was more suitable for the data and research purposes of this study. Hence, the fixed effects model was used to verify the impact of variables such as financial constraints, government subsidies, and entrepreneurial spirit on enterprise innovation.

Table 4 reports the regression analysis results obtained using the fixed effects model. Models (1–4) show that the government subsidy coefficients were 0.206, 0.881, 0.461, and 0.446, respectively. At the 1% level, this indicates a significant positive correlation between government subsidies and corporate innovation.

Baseline regression.

| variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Governmental Subsidy | 0.206⁎⁎⁎ | 0.881⁎⁎⁎ | 0.461⁎⁎⁎ | 0.446⁎⁎⁎ |

| (0.036) | (0.098) | (0.097) | (0.097) | |

| Government Subsidy Square | −0.415⁎⁎⁎ | −0.224⁎⁎⁎ | −0.221⁎⁎⁎ | |

| (0.057) | (0.056) | (0.056) | ||

| Financial Constraint | −0.107⁎⁎⁎ | −0.118⁎⁎⁎ | ||

| (0.006) | (0.007) | |||

| Entrepreneurship | 0.046⁎⁎⁎ | 0.045⁎⁎⁎ | ||

| (0.002) | (0.002) | |||

| Asset-liability Ratio | −0.002 | |||

| (0.028) | ||||

| Asset Turnover Ratio | 0.062⁎⁎⁎ | |||

| (0.014) | ||||

| Cash Flow | 0.311 | |||

| (0.236) | ||||

| Operating Receipt | 0.445 | |||

| (0.681) | ||||

| Tobin Q | −0.013⁎⁎⁎ | |||

| (0.003) | ||||

| Concentration Ratio | 0.003 | |||

| (0.008) | ||||

| Constant | 0.932⁎⁎⁎ | 0.918⁎⁎⁎ | 0.636⁎⁎⁎ | 0.586⁎⁎⁎ |

| (0.022) | (0.022) | (0.024) | (0.026) | |

| Time/industry/region | control | control | control | control |

| N | 31,144 | 31,144 | 31,144 | 31,144 |

| R2 | 0.034 | 0.051 | 0.197 | 0.197 |

Note: Standard errors in parentheses *p<0.1, **p<0.05, ***p< 0.01. Robust standard errors are in brackets.

The government subsidy square coefficients were −0.415, −0.224, and −0.221. At the 1% level as well, this indicates a significant negative correlation between the square of government subsidies and corporate innovation. This suggests an inverted "U" relationship between government subsidies and corporate innovation.

The promotion effect begins to weaken and even shifts to inhibit the level of government subsidies before it reaches a certain point. Financial constraints were negatively correlated with enterprise innovation which supports our research hypothesis. This infers that financial constraints weaken enterprise innovation activities.

The entrepreneurial spirit was positively correlated with enterprise innovation. The hypothesis of this study also verifies and demonstrates that entrepreneurial spirit can significantly promote enterprise innovation. In addition, the regression results of the control variables showed a negative correlation between Tobin's Q and enterprise innovation and a positive correlation between asset turnover and enterprise innovation.

Robustness testsRobustness test I: Variable Replacement Method. The financial constraints of listed companies estimated using the SA method can explain the relationship between operating income and financial constraints. However, the SA method is only a relative evaluation of the KZ method, rather than an absolute efficiency evaluation. The accuracy of the evaluation may be affected by a negative operating income or an improper output variable.

Although the estimation results using innovation input as the explanatory variable has validated Hypothesis 1 of this study, enterprise innovation input is an absolute variable and is unable to show the relative value of enterprise innovation input to enterprise innovation expenditure. As a result, this may also affect the accuracy of the evaluation. Thus, the proportion of innovative personnel may produce more accurate results by replacing the explanatory variable of R&D input. Based on this, we replaced the financial constraint of the SA index and R&D input variable and re-conducted the regression analysis.

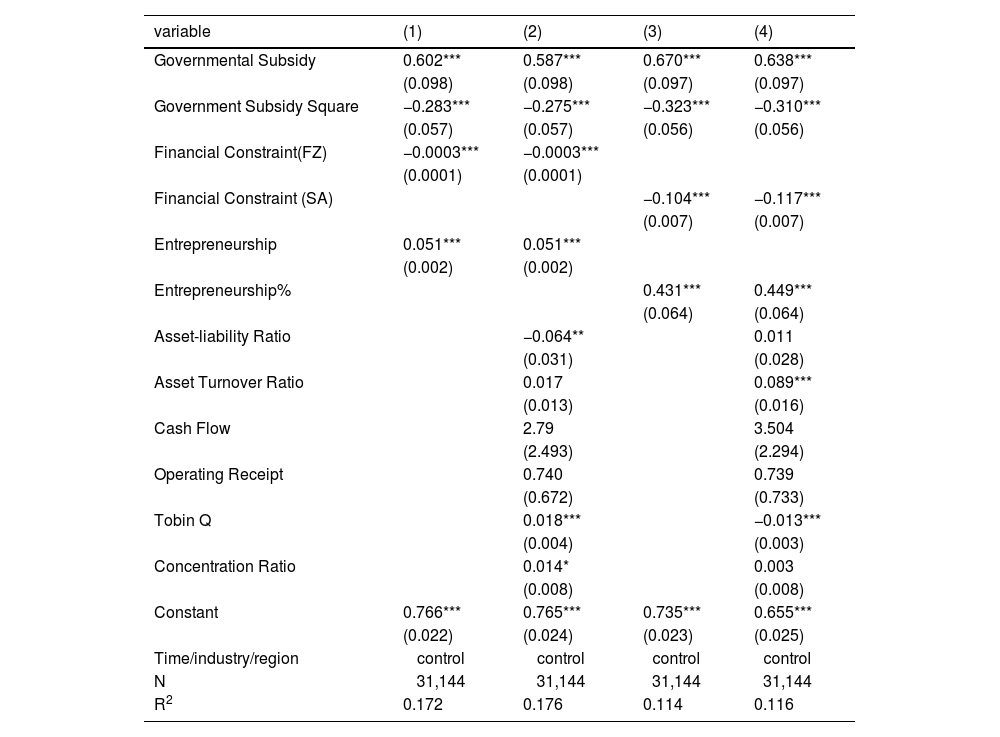

Table 5 reports the regression results obtained after variable replacement. Models (1–4) indicate that the government subsidy coefficients were 0.602, 0.587, 0.670, and 0.638. While the financial constraint coefficients were −0.0003, −0.0003, −0.104, and −0.117. All of which were at the significate 1% level. This suggests a positive correlation between government subsidies, entrepreneurial spirit, and corporate innovation while financial constraints inhibit corporate innovation.

Substitution variable method.

| variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Governmental Subsidy | 0.602*** | 0.587*** | 0.670*** | 0.638*** |

| (0.098) | (0.098) | (0.097) | (0.097) | |

| Government Subsidy Square | −0.283*** | −0.275*** | −0.323*** | −0.310*** |

| (0.057) | (0.057) | (0.056) | (0.056) | |

| Financial Constraint(FZ) | −0.0003*** | −0.0003*** | ||

| (0.0001) | (0.0001) | |||

| Financial Constraint (SA) | −0.104*** | −0.117*** | ||

| (0.007) | (0.007) | |||

| Entrepreneurship | 0.051*** | 0.051*** | ||

| (0.002) | (0.002) | |||

| Entrepreneurship% | 0.431*** | 0.449*** | ||

| (0.064) | (0.064) | |||

| Asset-liability Ratio | −0.064** | 0.011 | ||

| (0.031) | (0.028) | |||

| Asset Turnover Ratio | 0.017 | 0.089*** | ||

| (0.013) | (0.016) | |||

| Cash Flow | 2.79 | 3.504 | ||

| (2.493) | (2.294) | |||

| Operating Receipt | 0.740 | 0.739 | ||

| (0.672) | (0.733) | |||

| Tobin Q | 0.018*** | −0.013*** | ||

| (0.004) | (0.003) | |||

| Concentration Ratio | 0.014* | 0.003 | ||

| (0.008) | (0.008) | |||

| Constant | 0.766*** | 0.765*** | 0.735*** | 0.655*** |

| (0.022) | (0.024) | (0.023) | (0.025) | |

| Time/industry/region | control | control | control | control |

| N | 31,144 | 31,144 | 31,144 | 31,144 |

| R2 | 0.172 | 0.176 | 0.114 | 0.116 |

Note: Standard errors in parentheses *p<0.1, **p<0.05, ***p< 0.01. Robust standard errors are in brackets.

Robustness Test II: Regression Replacement Method. To test the robustness of the empirical results, we used the regression replacement method to test the baseline model. The baseline model used a panel data fixed effects regression, and the replacement models used the OLS and the random effects models, respectively. The OLS replacement model was used because it doesn't consider individual differences and time effects. This can test the importance of individual differences and time effects in the baseline model.

When a significant difference between the OLS replacement and baseline model results occurred, it indicates that individual differences and time effects play an important role in the model. Thus, the baseline model was more reliable. The purpose of the random effects model replacement was to test the impact of both random and fixed effects on the explanatory variables. The fixed effects model assumes that individual effects were related to the explanatory variables, while the random effects model wasn't related.

When a significant difference between the random effects replacement results and the fixed effects baseline results occurred, the individual effects and the explanatory variables were related. This led to the fixed effects model being more appropriate. Conversely, if the results of both models are consistent, individual effects are weakly related to the explanatory variables, and the random effects model is also reasonable.

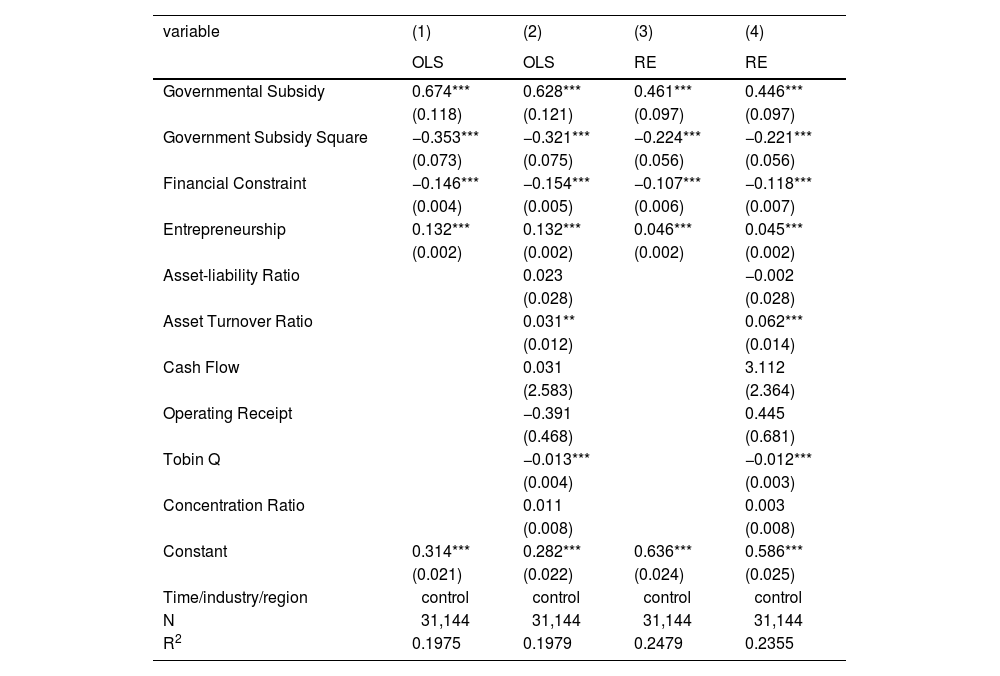

The results in Table 6 were obtained by using the regression replacement method. Models (1)-(4) indicate that the government subsidy coefficients were 0.674, 0.628, 0.461, and 0.446, while the financial constraint coefficients were −0.146, −0.154, −0.107, and −0.118. These findings passed the significance test. This suggests a positive correlation between government subsidies, entrepreneurial spirit, and corporate innovation while financial constraints inhibit corporate innovation. The results indicate that the estimates are still robust.

Regression Replacement Method.

| variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OLS | OLS | RE | RE | |

| Governmental Subsidy | 0.674*** | 0.628*** | 0.461*** | 0.446*** |

| (0.118) | (0.121) | (0.097) | (0.097) | |

| Government Subsidy Square | −0.353*** | −0.321*** | −0.224*** | −0.221*** |

| (0.073) | (0.075) | (0.056) | (0.056) | |

| Financial Constraint | −0.146*** | −0.154*** | −0.107*** | −0.118*** |

| (0.004) | (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.007) | |

| Entrepreneurship | 0.132*** | 0.132*** | 0.046*** | 0.045*** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Asset-liability Ratio | 0.023 | −0.002 | ||

| (0.028) | (0.028) | |||

| Asset Turnover Ratio | 0.031** | 0.062*** | ||

| (0.012) | (0.014) | |||

| Cash Flow | 0.031 | 3.112 | ||

| (2.583) | (2.364) | |||

| Operating Receipt | −0.391 | 0.445 | ||

| (0.468) | (0.681) | |||

| Tobin Q | −0.013*** | −0.012*** | ||

| (0.004) | (0.003) | |||

| Concentration Ratio | 0.011 | 0.003 | ||

| (0.008) | (0.008) | |||

| Constant | 0.314*** | 0.282*** | 0.636*** | 0.586*** |

| (0.021) | (0.022) | (0.024) | (0.025) | |

| Time/industry/region | control | control | control | control |

| N | 31,144 | 31,144 | 31,144 | 31,144 |

| R2 | 0.1975 | 0.1979 | 0.2479 | 0.2355 |

Note: Standard errors in parentheses *p<0.1, **p<0.05, ***p< 0.01. Robust standard errors are in brackets.

Robustness Test III: Instrumental Variable Method. To overcome the potential omitted variable and endogeneity problems in the baseline regression, this study conducted a two-stage instrumental variable estimation using provincial universities as the instrumental variable.

The selection of provincial universities was primarily based on three considerations: First, a higher number of provincial universities was correlated to a better educational environment. An excellent educational environment has an agglomeration effect, which continuously attracts talents, resources, and policy support. This also led to continuously improving the competitive environment of a regional market economy (Nam et al., 2019; Ismail et al., 2020).

Therefore, there was a correlation between the number of universities and government subsidies. Second, the number of universities, expenditure on higher education, and government subsidies of enterprises were exogenous. Knowledge spillover into the educational environment was in line with the endogeneity requirements. Therefore, using the educational environment as an instrumental variable can better solve the issue of correlation and exogeneity.

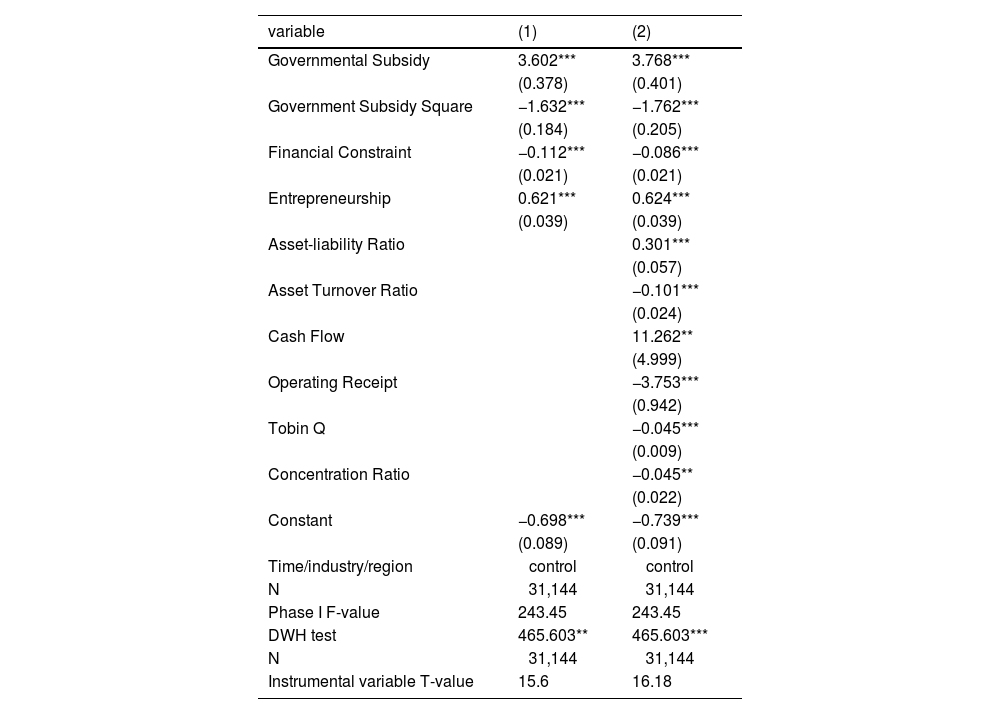

Table 7 reports the regression results of the instrumental variable method. The test results show that the DHK test rejected the null hypothesis. This indicates that the number of provincial universities was an endogenous explanatory variable. The first stage f-values were all greater than 16.38. Therefore, there was no weak instrumental variable problem.

Robustness testing instrumental variable approach.

| variable | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Governmental Subsidy | 3.602*** | 3.768*** |

| (0.378) | (0.401) | |

| Government Subsidy Square | −1.632*** | −1.762*** |

| (0.184) | (0.205) | |

| Financial Constraint | −0.112*** | −0.086*** |

| (0.021) | (0.021) | |

| Entrepreneurship | 0.621*** | 0.624*** |

| (0.039) | (0.039) | |

| Asset-liability Ratio | 0.301*** | |

| (0.057) | ||

| Asset Turnover Ratio | −0.101*** | |

| (0.024) | ||

| Cash Flow | 11.262** | |

| (4.999) | ||

| Operating Receipt | −3.753*** | |

| (0.942) | ||

| Tobin Q | −0.045*** | |

| (0.009) | ||

| Concentration Ratio | −0.045** | |

| (0.022) | ||

| Constant | −0.698*** | −0.739*** |

| (0.089) | (0.091) | |

| Time/industry/region | control | control |

| N | 31,144 | 31,144 |

| Phase I F-value | 243.45 | 243.45 |

| DWH test | 465.603** | 465.603*** |

| N | 31,144 | 31,144 |

| Instrumental variable T-value | 15.6 | 16.18 |

Note: Standard errors in parentheses *p<0.1, **p<0.05, ***p< 0.01. Robust standard errors are in brackets.

The t-values of the first-stage instrumental variable were 15.6 and 16.18, respectively. Hence, the number of provincial universities was closely related to the entrepreneurial spirit. As seen in Table 7, the government subsidy coefficients were 3.602 and 3.768. The government subsidy square coefficients were −1.632 and −1.762, and the financial constraint coefficients were −0.112 and −0.086. These all pass the significance test.

Government subsidies and entrepreneurial spirit were positively correlated with enterprise innovation, while financial constraints inhibit enterprise innovation. These previous regression results were consistent and indicate the estimates of this study were robust.

Mechanism and heterogeneity analysisThe moderating role of entrepreneurshipThe entrepreneurial spirit is the most important intangible asset of individual entrepreneurs. This is a significant resource in the knowledge-based economy. It is also a driving force for the timely adjustment of production factors and conducting enterprise innovation activities. Therefore, entrepreneurial spirit is not only an important influencing factor but should also be embedded as a regulatory variable in the research framework of enterprise innovation activities (Ziyae & Sadeghi, 2020). Based on this, this study examines entrepreneurial spirit as a regulatory variable.

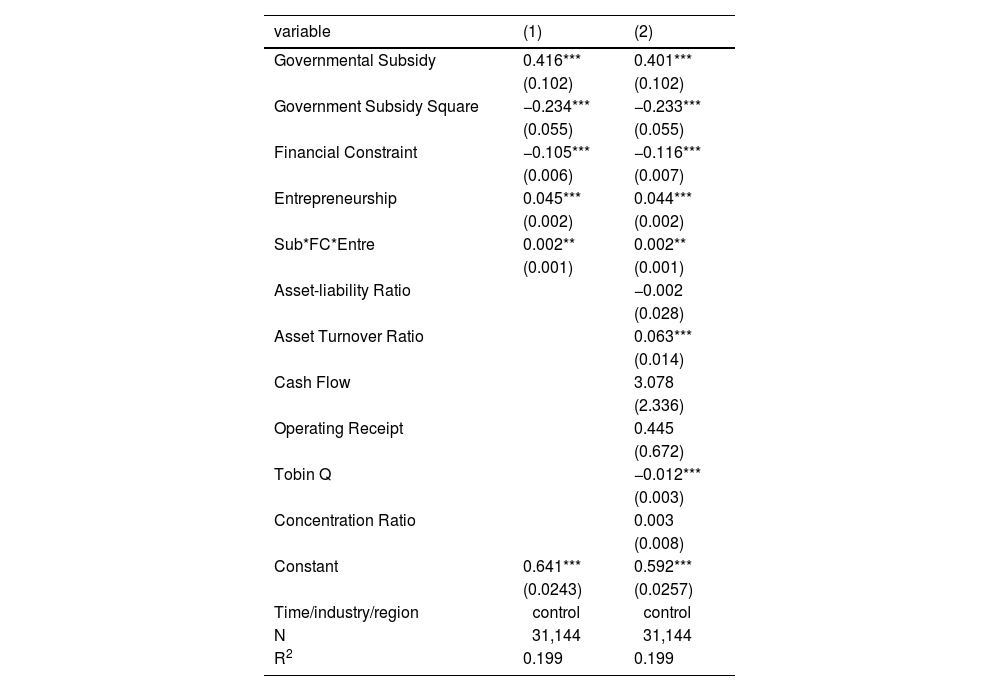

Table 8 reports the regression results of the regulatory effect. Models (1) and (2) show the Government Subsidy coefficients were 0.416 and 0.401. Government Subsidy Square coefficients were −0.234 and −0.233, while the Financial Constraint coefficients were −0.105 and −0.116. These all pass the significance test. There was a significant positive correlation between government subsidies and entrepreneurial spirit with corporate innovation, while financial constraints greatly inhibit it.

The moderating role of entrepreneurship.

| variable | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Governmental Subsidy | 0.416*** | 0.401*** |

| (0.102) | (0.102) | |

| Government Subsidy Square | −0.234*** | −0.233*** |

| (0.055) | (0.055) | |

| Financial Constraint | −0.105*** | −0.116*** |

| (0.006) | (0.007) | |

| Entrepreneurship | 0.045*** | 0.044*** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Sub*FC*Entre | 0.002** | 0.002** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Asset-liability Ratio | −0.002 | |

| (0.028) | ||

| Asset Turnover Ratio | 0.063*** | |

| (0.014) | ||

| Cash Flow | 3.078 | |

| (2.336) | ||

| Operating Receipt | 0.445 | |

| (0.672) | ||

| Tobin Q | −0.012*** | |

| (0.003) | ||

| Concentration Ratio | 0.003 | |

| (0.008) | ||

| Constant | 0.641*** | 0.592*** |

| (0.0243) | (0.0257) | |

| Time/industry/region | control | control |

| N | 31,144 | 31,144 |

| R2 | 0.199 | 0.199 |

Note: Standard errors in parentheses *p<0.1, **p<0.05, ***p< 0.01. Robust standard errors are in brackets.

The interactive terms of government subsidies, financial constraints, and entrepreneurial spirit were also positively correlated with enterprise innovation. This indicates that entrepreneurial spirit was a significant mechanism by which government subsidies and financial constraints affect enterprise innovation. Entrepreneurial spirit not only promotes enterprise innovation but also plays a role in resource allocation in optimizing the impact of government subsidies and financial constraints.

This confirms Hypothesis 2 of this study. Entrepreneurial spirit enhances the incentive mechanism of government subsidies and weakens financial constraints by coordinating their roles. As a result, it has an important impact on enterprise innovation.

Overall, the regression results show that government subsidies, financial constraints, and entrepreneurial spirit all have a direct impact on enterprise innovation. Entrepreneurial spirit also was the mechanism by which government subsidies and financial constraints affect enterprise innovation.

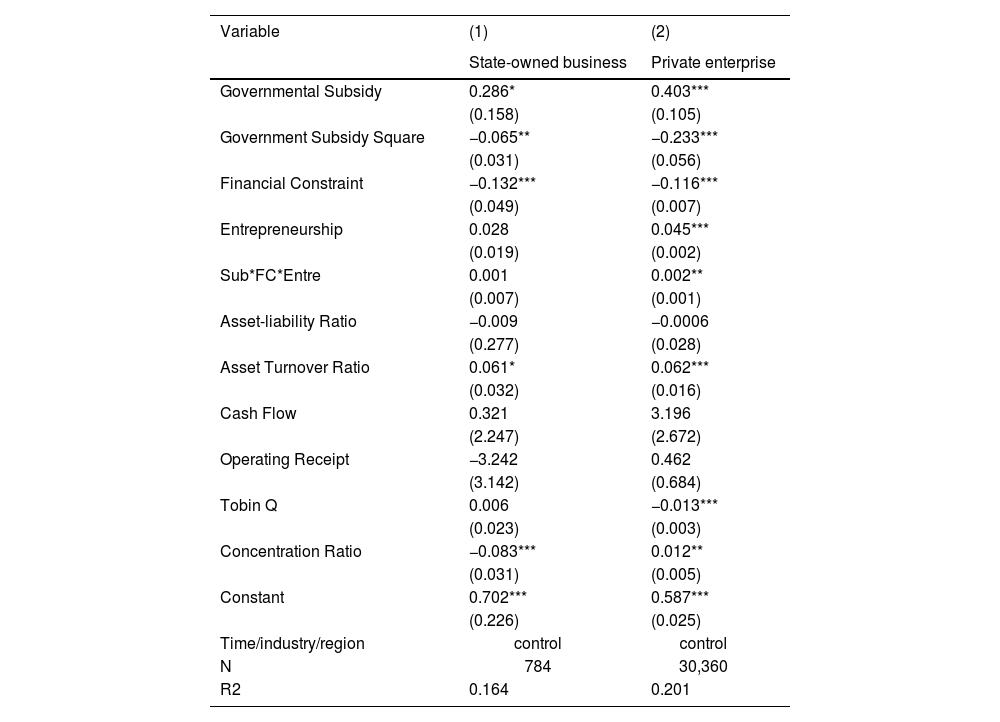

Heterogeneity analysis: different property rightsThe regulation mechanism of entrepreneurial spirit on innovation activities affects the various types of enterprises differently. Research has shown that state-owned enterprises have advantages in financing and operating activities due to government credit support, while private enterprises reach these advantages after a certain scale (She et al., 2021). In addition, state-owned enterprises partially bear the government's intentions, which leads to government subsidies being more favorable to them.

To test the impact of entrepreneurial spirit on innovation among different property rights enterprises, we generated interactive terms of government subsidies, entrepreneurial spirit, and financial constraints. This led to a classification analysis being conducted to test the regulatory mechanism of entrepreneurial spirit on innovation in different enterprises.

Table 9 reports the regression results of the moderating effects of different products. The results of Model (1) indicate that the Governmental Subsidy coefficient of 0.286 was at the significant 10% level, while the Government Subsidy Square coefficient of −0.065 was at the significant 5% level. The Financial Constraint coefficient of −0.132 was at the significant 1% level. Both the Entrepreneurship coefficient and the Sub*FC*Entre coefficient failed to pass the significance test at 0.028 and 0.001, respectively.

Different property rights regression results.

| Variable | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| State-owned business | Private enterprise | |

| Governmental Subsidy | 0.286* | 0.403*** |

| (0.158) | (0.105) | |

| Government Subsidy Square | −0.065** | −0.233*** |

| (0.031) | (0.056) | |

| Financial Constraint | −0.132*** | −0.116*** |

| (0.049) | (0.007) | |

| Entrepreneurship | 0.028 | 0.045*** |

| (0.019) | (0.002) | |

| Sub*FC*Entre | 0.001 | 0.002** |

| (0.007) | (0.001) | |

| Asset-liability Ratio | −0.009 | −0.0006 |

| (0.277) | (0.028) | |

| Asset Turnover Ratio | 0.061* | 0.062*** |

| (0.032) | (0.016) | |

| Cash Flow | 0.321 | 3.196 |

| (2.247) | (2.672) | |

| Operating Receipt | −3.242 | 0.462 |

| (3.142) | (0.684) | |

| Tobin Q | 0.006 | −0.013*** |

| (0.023) | (0.003) | |

| Concentration Ratio | −0.083*** | 0.012** |

| (0.031) | (0.005) | |

| Constant | 0.702*** | 0.587*** |

| (0.226) | (0.025) | |

| Time/industry/region | control | control |

| N | 784 | 30,360 |

| R2 | 0.164 | 0.201 |

Note: Standard errors in parentheses *p<0.1, **p<0.05, ***p< 0.01. Robust standard errors are in brackets.

Model (2) shows a Governmental Subsidy coefficient of 0.403, a Government Subsidy Square coefficient of −0.233, a Financial Constraint coefficient of −0.116, and an Entrepreneurship coefficient of 0.045. All four were at the significant 1% level. The Sub*FC*Entre coefficient of 0.002 was at the significant 5% level.

The results of Model (1),(2) show that the absolute value of the coefficients of government subsidies, entrepreneurial spirit, and interactive terms for private enterprises were higher than that of state-owned enterprises and have passed the significance test. This indicates that entrepreneurial spirit was more important for private enterprises in optimizing the impact of government subsidies than their state-owned counterparts.

The results of the classification analysis show the differences in the regulatory role of entrepreneurial spirit on innovation among various types of enterprises. For private enterprises, entrepreneurial spirit directly affects innovation as well as regulates the effect of government subsidies. This plays an important role in the allocation of innovation resources. However, the direct impact and regulatory role of entrepreneurial spirit was not significant for state-owned enterprises.

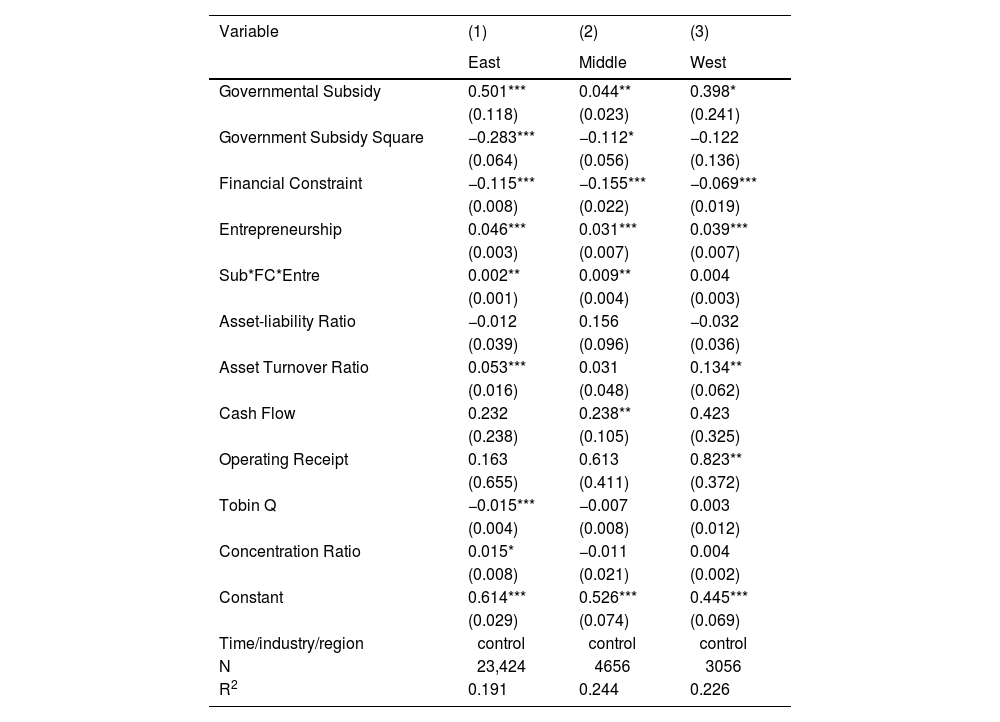

Heterogeneity analysis: different regionsEntrepreneurial innovation's technology orientation both directly affects enterprise innovation and regulates the mechanisms of government subsidies and external resource constraints. However, the innovation environment may lead to differences in entrepreneurial innovation's technology orientation across regions (Zheng & Zhao, 2017).

The impact of entrepreneurial innovation's technology orientation on enterprise innovation in different environments was tested by conducting a heterogeneous analysis on regional economic development levels. The economically developed eastern, underdeveloped western, and transitioning central regions were selected to examine the differences in the impact of subsidy policies on various regions.

Table 10 presents the regression results of the different regional regulatory effects. Models (1), (2), and (3) estimate the effects in the eastern, central, and western regions, respectively. The Governmental Subsidy coefficients passed the significance test at 0.501, 0.044, and 0.398. The Government Subsidy Square coefficients were −0.283, −0.112, and −0.122 with only Model (3) failing the significance test. The Financial Constraint coefficients were −0.115, −0.155, and −0.069, and the Entrepreneurship coefficients were 0.046, 0.031, and 0.039. Both of which passed the significance test. The Sub*FC*Entre coefficients were 0.002, 0.009, and 0.004 with only Model (3) failing the significance test.

Different regional regression results.

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| East | Middle | West | |

| Governmental Subsidy | 0.501*** | 0.044** | 0.398* |

| (0.118) | (0.023) | (0.241) | |

| Government Subsidy Square | −0.283*** | −0.112* | −0.122 |

| (0.064) | (0.056) | (0.136) | |

| Financial Constraint | −0.115*** | −0.155*** | −0.069*** |

| (0.008) | (0.022) | (0.019) | |

| Entrepreneurship | 0.046*** | 0.031*** | 0.039*** |

| (0.003) | (0.007) | (0.007) | |

| Sub*FC*Entre | 0.002** | 0.009** | 0.004 |

| (0.001) | (0.004) | (0.003) | |

| Asset-liability Ratio | −0.012 | 0.156 | −0.032 |

| (0.039) | (0.096) | (0.036) | |

| Asset Turnover Ratio | 0.053*** | 0.031 | 0.134** |

| (0.016) | (0.048) | (0.062) | |

| Cash Flow | 0.232 | 0.238** | 0.423 |

| (0.238) | (0.105) | (0.325) | |

| Operating Receipt | 0.163 | 0.613 | 0.823** |

| (0.655) | (0.411) | (0.372) | |

| Tobin Q | −0.015*** | −0.007 | 0.003 |

| (0.004) | (0.008) | (0.012) | |

| Concentration Ratio | 0.015* | −0.011 | 0.004 |

| (0.008) | (0.021) | (0.002) | |

| Constant | 0.614*** | 0.526*** | 0.445*** |

| (0.029) | (0.074) | (0.069) | |

| Time/industry/region | control | control | control |

| N | 23,424 | 4656 | 3056 |

| R2 | 0.191 | 0.244 | 0.226 |

Note: Standard errors in parentheses *p<0.1, **p<0.05, ***p< 0.01. Robust standard errors are in brackets.

Comparing the results, we find that the impact of government subsidies on firm innovation decreases from east to west, while the impact of financial constraints on firm innovation increases from east to west. The impact of entrepreneurial spirit on firm innovation shows a "U" shape, and the moderating effect of entrepreneurial spirit exhibits an inverted "U" shape.

This can be attributed to a more developed market economy and innovation environment in the eastern region which led to the incentives of government subsidies being more prominent and financial channels being more accessible. In contrast, the Western region's underdeveloped market mechanisms and financial difficulties resulted in the limited promotion of firm innovation through government subsidies.

The central region is undergoing a transition period with a changing market mechanism and innovation environment. Entrepreneurial spirit plays an essential role in connecting government subsidies, financial channels, and firm innovation. Its moderating effect shows an inverted "U" shape.

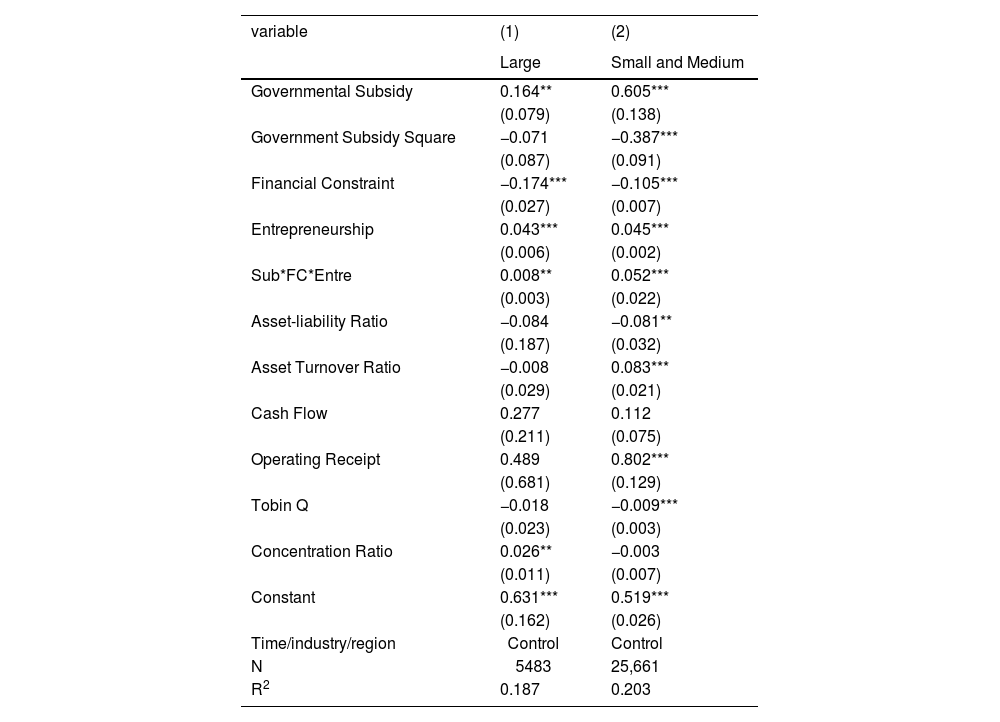

Heterogeneity analysis: different business scaleGovernment subsidies have different effects on companies of various sizes. Özçelik and Taymaz(2008) suggest that government subsidies have a greater impact on innovation in small businesses than large businesses. In contrast, Méndez-Morales et al. (2019) argue that government subsidies have a crowding-out effect on innovation investment within small and medium-sized enterprises.

To examine the moderating effect of entrepreneurial spirit on innovation in enterprises of different sizes, we classified the enterprises based on their annual revenue. Enterprises with annual revenues exceeding 5 billion yuan were classified as large enterprises, while those with revenues below 5 billion yuan were classified as small and medium-sized enterprises.

Table 11 presents the regression results of different moderating effects. Model (1) shows that government subsidies and entrepreneurial spirit were positively related to firm innovation, while financial constraints were negatively related to firm innovation. The interaction coefficient of 0.008 was at the significant 5% level which indicates that in large enterprises, entrepreneurial spirit promotes the effect of government subsidies on firm innovation.

Different business scale regression results.

| variable | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Large | Small and Medium | |

| Governmental Subsidy | 0.164** | 0.605*** |

| (0.079) | (0.138) | |

| Government Subsidy Square | −0.071 | −0.387*** |

| (0.087) | (0.091) | |

| Financial Constraint | −0.174*** | −0.105*** |

| (0.027) | (0.007) | |

| Entrepreneurship | 0.043*** | 0.045*** |

| (0.006) | (0.002) | |

| Sub*FC*Entre | 0.008** | 0.052*** |

| (0.003) | (0.022) | |

| Asset-liability Ratio | −0.084 | −0.081** |

| (0.187) | (0.032) | |

| Asset Turnover Ratio | −0.008 | 0.083*** |

| (0.029) | (0.021) | |

| Cash Flow | 0.277 | 0.112 |

| (0.211) | (0.075) | |

| Operating Receipt | 0.489 | 0.802*** |

| (0.681) | (0.129) | |

| Tobin Q | −0.018 | −0.009*** |

| (0.023) | (0.003) | |

| Concentration Ratio | 0.026** | −0.003 |

| (0.011) | (0.007) | |

| Constant | 0.631*** | 0.519*** |

| (0.162) | (0.026) | |

| Time/industry/region | Control | Control |

| N | 5483 | 25,661 |

| R2 | 0.187 | 0.203 |

Note: Standard errors in parentheses *p<0.1, **p<0.05, ***p< 0.01. Robust standard errors are in brackets.

Model (2) shows that government subsidies and entrepreneurial spirit were positively related to firm innovation, while financial constraints were negatively related to firm innovation. The interaction coefficient of 0.052 was at the significant 1% level. This indicates that for small and medium-sized enterprises, entrepreneurial spirit has a direct impact on innovation and moderates the effect of government subsidies.

Based on the comparison between Models (1) and (2), the impact of government subsidies on innovation in small and medium-sized enterprises was greater than in large enterprises. Due to economies of scale, large enterprises can rely more on internal resources for innovation activities and less on government subsidies. In contrast, small and medium-sized enterprises face greater financial constraints which led to the incentive mechanism of government subsidies being more critical.

DiscussionThe impact of government subsidies on firm innovation from the perspective of entrepreneurship and financial constraints was analyzed using data from Chinese-listed firms. The empirical evidence proves that government subsidies have an incentive effect on firm innovation.

The results of this study are not consistent with some scholars. They argue that there is a substitution and crowding out effect of government subsidies on private investment under efficient market conditions. This reduces economic growth and welfare, and the peer effect also puts new entrants at a disadvantage (She et al. 2021; Acemoglu et al., 2013; Takalo et al., 2013). There are three main reasons for this conclusion:

- 1)

A segment of scholars emphasizes the importance of institutions and property rights. They argue that under conditions of efficient markets and comprehensive property rights, the market was optimized in allocating resources, and the intervention of government subsidies will break this optimum (Redford,2020). Aschhoff (2008) finds that firms that have previously received government funding are likely to receive it again which may lead to innovation market failures (Takalo, 2013).

- 2)

Another segment of scholars has highlighted the relationship between the size of government grants and innovation efficiency. They argue that government grants and innovation show a U-shape. Arqué-Castells and Mohnen (2012) argue that sunk costs were an R&D entry barrier for some firms. Thus, Huang et al. (2016) argue that a firm's innovation efficiency increases only when government subsidies reach a certain size.

- 3)

In addition, some scholars analyze the crowding-out effect of government subsidies in terms of knowledge externalities. Radicic (2020) argues that the non-competitive and exotic nature of technological knowledge leads to government subsidies squeezing private investment.

The explanations for the differences in the research findings are: First, existing studies generally ignore the driving force of entrepreneurship in the process of corporate innovation. The innovation bias of entrepreneurs is strongly goal-oriented and destructive. This determines that entrepreneurship has a regulating effect in resource allocation and the development of corporate innovation. Thus, productive entrepreneurship will rationalize the use of resources and promote corporate innovation.

Second, the assumption of efficient markets is invalid. Information asymmetry and transaction costs dictating that firms face factor-bound dilemmas in innovation markets. While government subsidies have an incentive effect on firm innovation, there is considerable heterogeneity which is highlighted by two things:

First, the nature of property rights is more efficient for private firms than their state-owned counterparts. Our findings are also a confirmation for Ren (2022), Takalo (2013), Wenqi et al.(2022), and others. They argue that under conditions of innovation market failure, the cost of external financing is much lower for state-owned firms than for private firms. Government support for a private firm's innovation has an additional effect that reduces that firm's fixed R&D costs and external financial costs. As a result, it leads to a spillover effect on a firm's innovation.

The second is the scale of operation. We find that government subsidies have a larger effect on innovation in small firms than in large firms. Similar conclusions have been reached by Méndez (2019), Ozcelik & Taymaz (2008), Xu et al. (2021), and others. In addition, we find that private entrepreneurships are better able to optimize government subsidies than state-owned firms, and SME entrepreneurship weakens the impact of government subsidies on firm innovation.

Conclusions and recommendationsThe innovation-driven strategy leading to the high-quality development of enterprises has become an important driving force for China's economic development. Against the backdrop of a century of unprecedented changes, scientific adherence and technological innovation has an important role to play in China's response to emergencies, environmental pollution, and climate change.

By using entrepreneurship as an entry point, this research explores the impact of government subsidies and financial constraints on corporate innovation based on data from China's A-share unlisted companies from 2012 to 2020. In the benchmark regressions, it is found that government subsidies stimulate a firm's innovation activities while financial constraints hinder them. The robustness of the findings was tested by the alternative and instrumental variables method.

By generating interaction terms for the following, the moderating effects were found to be decreasing from east to central for entrepreneurship on government subsidies and from central to east for financial constraints. Private entrepreneurships are better able to optimize government subsidies than state-owned enterprises. Our research has important implications for formulating policies and implementing innovation-driven strategies.

First, government subsidies play a crucial role in stimulating enterprise innovation activities. This indicates that government subsidy policies have significant effects on promoting technological innovation in enterprises. Therefore, the government should continue to increase R&D subsidy investment, expand the subsidy scope, encourage more enterprises to participate, and further stimulate enterprise innovation potential by promoting industrial upgrading.

Second, the inhibitory effect of financial constraints on enterprise innovation activities cannot be ignored. This suggests that the government should further expand direct channels to relax financial restrictions of small and medium-sized enterprises. At present, the government should also increase innovation efforts by having financial institutions develop specialized products and services for them. The improvement of the financial environment will help them unleash their innovation vitality.

The specific content includes several points: First, encourage banks to open green channels for innovative enterprises. Second, support the establishment of innovation projects to support enterprises subject to financial constraints. Third, establish a digital financial service platform to solve the dilemma of innovative information asymmetry.

Third, the moderating role of entrepreneurial spirit on government subsidies and financial constraints indicates that various enterprises respond differently to policy tools. This suggests that the government should consider the different characteristics of enterprises and adopt a more refined and targeted policy for them. This can improve the effectiveness of policies, avoid duplication, and waste of resources.

Fourth, the moderating role of entrepreneurial spirit in the effects of government subsidies and financial constraints cannot be ignored. The government should strengthen the support of entrepreneurial spirit and encourage entrepreneurs to play an active role in the innovation process. Entrepreneurs should enhance their awareness of innovation and use new technologies to transform their business models. We should also pay attention to team synergy and create an environment that encourages innovation. In addition, a scientific incentive mechanism should be established to transform innovative thinking into practical actions to achieve results. At the same time, relevant policies and regulations should be improved to provide a better ecology to take advantage of entrepreneurs' talents.

Fifth, private and state-owned enterprises have their respective advantages in responding to government subsidies and financial constraints. This suggests that the government should adjust industrial policies, consider the needs of various enterprises, and coordinate the development of the private and state-owned economies.

LimitationsThis study explores the impact of government subsidies on enterprise innovation from the perspective of entrepreneurial spirit. It has made certain innovations in theoretical perspectives and content, but there are still some shortcomings that may inspire research ideas for other scholars and researchers.

First, our analysis focused on the available data on listed companies in China and disregarded unlisted small and medium-sized enterprises. Listed companies are more likely to obtain external financial support and have more active innovative activities. Thus, it difficult to generalize the research conclusions on a range of small businesses. Future research can obtain more comprehensive conclusions on small and medium-sized enterprises through other channels.

Second, regarding the quantitative analysis of innovation, many scholars measure innovation by the number of patent applications, but innovation is a multi-dimensional concept that cannot be solely reflected by the patent indicator. Evaluating the level and quality of enterprise innovation needs to be further explored, and more innovation measurement indicators will help improve the accuracy of the conclusions.

Third, entrepreneurial spirit plays an important role in innovation, but quantifying it is still a controversy. Although innovation investment was used as a substitute variable for entrepreneurial spirit, this is only one aspect of entrepreneurial spirit. Entrepreneurial spirit is a comprehensive quality that includes vision, wisdom, courage, perseverance, and many other aspects limited not only to a single variable. Therefore, it is important to accurately measure entrepreneurial spirit and design a comprehensive index system that reflects the study of enterprise innovation.

Re-entrepreneurship also plays an important role, but quantifying it is controversial as well. Although innovation input was considered a substitute variable, it is only one aspect of entrepreneurship. In fact, entrepreneurship is a multi-dimensional comprehensive concept. The core lies in the entrepreneur's vision, the courage to practice the action force and break the conventional innovation consciousness, the ability to handle risks, and so on.

Many challenges remain in quantifying entrepreneurship. First, the abstract aspects of foresight, insight, and decision-making power are difficult to be directly observed and quantified. A series of indirect proxy variables for measurements increases the difficulty. Second, different types of enterprises may require a variety of quantitative indicator systems. For example, enterprise value innovation and risk-taking are mature enterprises that need stability and collaboration.

This requires the complex task of designing the appropriate quantitative tools for each enterprise. Moreover, entrepreneurship is dynamic and changes with the life cycle of the business and the operating environment. Most quantitative tools rely on cross-sectional data, which makes it difficult to capture this dynamic evolution. Finally, many exogenous environmental factors affect entrepreneurship, such as cultural background, policy system, market conditions, and etc.

The combined impact of these factors also makes the quantification process complex. Therefore, the significance for enterprise innovation research is to accurately measure entrepreneurship and design a comprehensive index system to reflect it. This contributes a deeper understanding of the impact of entrepreneurship on enterprise innovation as well as provide quantitative tools for business management practice.

Fourth, innovation is an eternal research topic. The differences in conclusions are largely due to the shortcomings of theoretical frameworks. Most existing theories are based on the assumptions of complete rationality and information. Limited rationality and incomplete information are the norm in real markets. The construction of an enterprise innovation theoretical model under a limited rationality market environment still needs further exploration.

Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province No. KYCX20_1274): Study on Occupational Characteristics, credit Cost and borrowing behavior of grain Brokers.