The existing literature on SME internationalization has inadequately integrated joint innovation capabilities, organizational unlearning, and the internationalization process. Previous studies have primarily examined these concepts separately, obscuring their interconnection and reciprocal impact. This study fills in a gap in the literature and responds to calls for more studies (e.g., Du, Zhu & Li, 2023; Genc, Dayan & Genc, 2019) by developing and testing a moderated mediation model to examine how joint innovation capabilities affect exploratory innovation through the mediating role of organizational unlearning. The research also examines the moderating effect of the degree of internationalization on this relationship. A cross-sectional survey was conducted with 300 logistics and general managers from SMEs in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), utilizing partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) to evaluate the measurement models' validity and reliability, and to test the hypothesized relationships. The results demonstrate that organizational unlearning is a key mechanism linking collaborative innovation capabilities with exploratory innovation. Additionally, the degree of internationalization significantly moderates this relationship, with a stronger mediation effect when internationalization is low. These findings provide practical implications for SMEs and managers, especially in overseeing innovation and unlearning processes while accounting for the degree of internationalization in their growth strategies. Managers in SMEs must recognize the complexities introduced by internationalization, such as diverse cultural norms and regulatory frameworks, which can impede the process of unlearning. To address these challenges, SMEs should consider adopting region-specific innovation strategies or investing in cross-cultural training to effectively manage the integration of diverse knowledge sources.

In today's fast-paced global market, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) must balance competitiveness with continuous innovation. One way SMEs can enhance innovation is through partnerships with suppliers, where joint innovation capabilities—built on shared knowledge, resources, and expertise—play a key role in developing new products and services (Cen et al., 2023; Ndubisi et al., 2020). However, for these collaborative capabilities to effectively drive exploratory innovation—focused on experimentation and knowledge creation—both collaboration and organizational unlearning are vital. Organizational unlearning, the process of discarding outdated knowledge and practices, enables SMEs to adapt to changing environments and embrace new ways of innovating (Hedberg, 1981; Leal-Rodríguez et al., 2015; Tsang & Zahra, 2008; Xi et al., 2020). Moreover, the degree of internationalization—reflecting how extensively a firm operates in global markets—further shapes these dynamics, as SMEs are exposed to diverse cultural, regulatory, and competitive environments, demanding agility and adaptability (Hilmersson et al., 2021; Reim et al., 2022).

This study examines how organizational unlearning mediates the relationship between joint innovation capabilities and exploratory innovation, and how the degree of internationalization moderates this relationship. By incorporating supplier collaboration and global presence into a unified framework, the study aims to shed light on how SMEs can leverage these factors to foster innovation. The analysis is grounded in dynamic capabilities and organizational learning theories. According to dynamic capabilities theory (Brewis et al., 2023), firms must constantly adjust their resources and abilities to thrive in changing environments. Joint innovation capabilities—SMEs’ ability to collaborate with suppliers to boost their innovation potential—are seen as a type of dynamic capability that enhances a firm's ability to innovate (Lin et al., 2022). However, to fully exploit these capabilities, firms must also engage in organizational unlearning to discard obsolete practices and adopt new approaches that better suit evolving market conditions, particularly in international contexts. Organizational learning theory (Argyris and Schön, 1978) emphasizes the need for ongoing learning and adjustment, with unlearning playing a critical role when companies face new challenges in global markets where previous knowledge may no longer be applicable (Klammer et al., 2024). The degree of internationalization influences how well firms can unlearn and apply new knowledge to enhance their innovation outcomes.

Previous research has demonstrated the importance of collaborative innovation capabilities in promoting exploratory innovation in SMEs. These capabilities enable firms to harness supplier knowledge and resources to create innovative products and processes (Robertson et al., 2023). However, the success of these partnerships often depends on the company's ability to adapt and respond to new challenges, making organizational unlearning an essential factor (Klammer & Gueldenberg, 2020). By discarding outdated practices, firms create space for new, market-relevant knowledge and methodologies, which is critical for remaining competitive and innovative (Zhao & Wang, 2020). Exploratory innovation is particularly vital for SMEs, as it allows them to experiment with new possibilities and drive future success (Sayed & Dayan, 2024).

Internationalization also has a direct impact on a firm's innovation and performance (Pastelakos et al., 2023). Engaging in global markets exposes firms to a broader range of experiences, challenges, and opportunities, which can enhance their ability to innovate (Zahra, Ireland, & Hitt, 2000). However, this increased exposure also requires firms to unlearn practices that may be effective in domestic markets but are less suitable internationally (Appiah et al., 2023).

Despite the extensive research on innovation, gaps remain. First, joint innovation capabilities, organizational unlearning, and internationalization have rarely been integrated into a single framework. Most studies have examined these concepts separately, limiting our understanding of their interplay (Du et al., 2023). Second, much of the existing literature focuses on large corporations, overlooking the unique challenges faced by SMEs, which often encounter different obstacles and opportunities in innovation and international expansion compared to larger firms. Finally, although the impact of internationalization on innovation has been well studied (Evers et al., 2023; Hilmersson et al., 2023), its role as a moderator between joint innovation capabilities, unlearning, and exploratory innovation—especially in SMEs—has not been thoroughly explored. This study aims to address these gaps by analyzing the relationships between joint innovation capabilities, organizational unlearning, and SME internationalization. In light of the identified gaps in the literature, this study examines the following research questions: “How does organizational unlearning mediate the relationship between joint innovation capabilities and exploratory innovation, and to what extent does internationalization moderate this relationship in SMEs?”

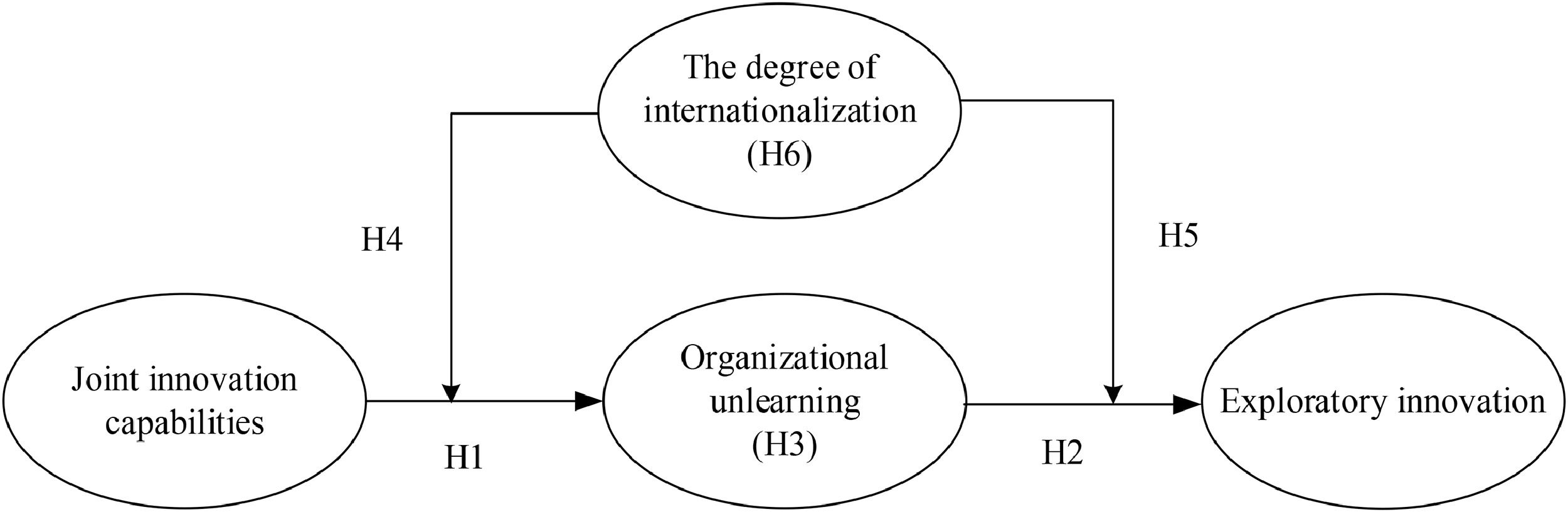

This research advances both dynamic capabilities and organizational learning theories in several ways. It expands the dynamic capabilities framework by emphasizing the role of organizational unlearning in enabling SMEs to adapt their joint innovation capabilities for exploratory innovation, stressing that unlearning is essential in dynamic environments. Additionally, the study contributes to organizational learning theory by highlighting the importance of unlearning in the internationalization process, demonstrating how SMEs must consistently abandon outdated practices to maintain competitiveness in global markets. By examining the moderating effect of internationalization on the relationship between joint innovation capabilities, unlearning, and exploratory innovation, the study offers practical insights into how SMEs can enhance their innovative performance through global expansion. The conceptual model outlining these relationships is depicted in Fig. 1.

Conceptual background and relevance of the contextOrganizational unlearning, dynamic capabilities and internationalizationModern markets are defined by constant change and uncertainty due to rapid technological advancements, economic volatility, and political instability (Schmitt et al., 2018). In this unstable environment, organizations must not only utilize their existing capabilities but also cultivate new ones to attain long-term success and sustain a competitive advantage (Kyrdoda et al., 2023). The notion of strategic renewal pertains to this adaptive process, emphasizing the significance of ongoing capability enhancement (Issah et al., 2023). Organizational learning is a critical element of strategic renewal, allowing firms to address the challenges posed by increasing global competition, diminishing product lifecycles, and technological advancements by harmonizing the utilization of existing knowledge with the pursuit of innovative approaches (Rashman et al., 2009). Exploration necessitates the adoption of innovative business models and the execution of disruptive, transformative processes within the organization (Zhou et al., 2020).

The dynamic capabilities framework, based on the resource-based view of the firm, elucidates how organizations can reorganize internal and external resources to attain a competitive advantage (Abraham et al., 2012). These capabilities develop over time and entail organizational routines that may require modification to alleviate competitive pressures. Dynamic capabilities are advantageous even in stable environments (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000) and can be classified into incremental dynamic capabilities and renewing dynamic capabilities (Ambrosini & Bowman, 2009).

Incremental dynamic capabilities denote gradual alterations of existing resource configurations, typically linked to exploitative innovation (Pang et al., 2023). These capabilities enable firms to utilize existing skills and competencies, thereby augmenting their products and services for current customers through enhanced internal processes and structures. Conversely, renewing dynamic capabilities requires a more intentional rejuvenation of the organization's resource foundation. This renewal necessitates the development, implementation, or reorganization of new resources to fundamentally alter the organization (Ambrosini & Bowman, 2009). Renewal capabilities are intricately associated with exploratory innovation, which aims to introduce novel business models and disruptive renewal processes (Anand et al., 2024). Incremental and renewing capabilities require alterations to the resource base: incremental capabilities enhance existing resources, whereas renewing capabilities intentionally expand or alter them (Mehralian et al., 2024). A third category, regenerative dynamic capabilities, is essential for enhancing an organization's dynamic skills rather than merely its resource base (Ambrosini & Bowman, 2009). These capabilities allow firms to shift from obsolete practices to new adaptive competencies that are key for survival in volatile environments (Kyrdoda et al., 2023). In this context, organizational unlearning is essential, as it enables firms to question and supplant entrenched knowledge and practices, thereby fostering innovation. Regenerative capabilities can generate new dynamic skills or augment existing ones, and their existence frequently influences a firm's success or failure (Das & Bocken, 2024).

This study promotes a transition from a static to a dynamic capability framework in the conceptualization of organizational unlearning. This framework integrates dynamic capabilities theory and organizational learning theory to elucidate the relationships among joint innovation capabilities, organizational unlearning, exploratory innovation, and internationalization. Dynamic capabilities emphasize the necessity of reconfiguring resources to adjust to evolving environments, whereas organizational learning highlights the importance of unlearning obsolete knowledge to enable this adaptation (Teece et al., 1997). These concepts are essential for companies aiming to maintain competitiveness in today's swiftly changing environment, as they underscore the importance of cultivating new skills and eliminating outdated practices.

In this context, internationalization profoundly influences the interplay between joint innovation capabilities, organizational unlearning, and exploratory innovation. As SMEs enter international markets, they face varied cultures, competitive landscapes, and external pressures that can either facilitate or obstruct their ability to unlearn and innovate (Berns, 2023). The dynamic capabilities of resource reconfiguration and the unlearning of obsolete knowledge are vital for firms operating in global markets, where adaptation to external demands is essential for maintaining competitive advantage. Companies with significant internationalization frequently need to undertake extensive unlearning to adapt to diverse external conditions and customer preferences (Zhou et al., 2010). The capacity to unlearn is essential for SMEs to eliminate domestically oriented practices and embrace globally pertinent knowledge and competencies (Johanson & Vahlne, 2009). In contrast, companies with reduced internationalization may encounter diminished external pressures to adapt, thereby restricting the necessity for unlearning. This insulation may limit their capacity to fully utilize joint innovation capabilities for exploratory innovation, as they are less exposed to varied knowledge sources (Hitt et al., 1997). The level of internationalization can either enhance or reduce the influence of organizational unlearning and collaborative innovation capabilities on exploratory innovation, contingent upon the degree of a firm's involvement in international markets.

Relevance of the study contextWe conduct a comprehensive examination of this theoretical framework in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), as elaborated in the Methods section (Section 4). Here, we provide a rationale for the theoretical significance of this context. Typically, we extend our attention beyond the usual emphasis on Western or Eastern Asian situations and respond to the demand for further investigation into innovation and internationalization process in Middle Eastern nations (Genc et al., 2019; Younis & Elbanna, 2022). However, it is worth noting that the economic and financial profile of the UAE is also intriguing, and our experiments with the suggested framework in the UAE provide valuable insights for countries with comparable cultural profiles.

Specifically, we argue that there are distinct factors that can enhance the robustness and credibility of the suggested connections, pertaining to both the mediation and moderation processes. First, the UAE has recently implemented a National Innovation Strategy in order to position itself as one of the world's most innovative countries within a span of seven years. The country delineates the seven priority sectors for these initiatives. SMEs, which are decisive to the country's economy, have the potential to take a prominent position in this national strategy by adopting a more innovative approach. The economic activities and overall adoption of the strategy can be significantly influenced by the government's initiatives as well as the capacity and inclination of SMEs to innovate. Hence, it is vital to bolster the internationalization and innovativeness of SMEs in the UAE in order to foster economic growth in the country. Second, the rapid expansion of global markets over the past three decades has had an impact on SMEs in the country, leading to a growing significance of internationalization (Caiazza, 2016). Due to the reduction of trade barriers and advancements in transportation technologies (Harris et al., 2015), SMEs have been experiencing accelerated growth in international markets. SMEs not only experience the advantages of increased internationalization, such as accessing more consumers and growth prospects, but also encounter significant difficulties due to rising global competition. Specifically, companies that fail to innovate are highly susceptible to international competition. Third, the UAE has made significant strides in diversifying its economy away from its traditional reliance on oil and gas, which have traditionally served as the foundation of its economy. Currently, industries such as tourism, aviation, real estate, trade, and financial services have a substantial impact on the country's gross domestic product (GDP), despite not being related to the oil sector. As of 2023, the non-oil sector accounts for around 70% of the UAE's GDP, indicating the effectiveness of the country's efforts to diversify its economy. Fourth, The UAE's advantageous geographical position at the crossroads of Asia, Europe, and Africa has established it as a pivotal global trade hub. The UAE is a prominent participant in the international aviation industry, boasting Emirates Airlines and Etihad Airways as two of the foremost global carriers. The nation's free zones, such as Jebel Ali Free Zone (JAFZA) and Dubai International Financial Centre (DIFC), entice foreign investments by providing incentives including tax exemptions and complete foreign ownership rights.

Hypotheses developmentMediating role of organizational unlearningThe integration of external knowledge into an organization's existing systems is a multifaceted process significantly shaped by the organization's current knowledge base, routines, and cognitive frameworks (Markus et al., 2002; Odec & Ayavoo, 2020). Organizational learning theory posits that organizations develop by assimilating, analyzing, and retaining knowledge, which subsequently influences their established processes and behaviors (Argote et al., 2021). Nonetheless, these established routines and cognitive frameworks can obstruct the effective utilization of new information, particularly when it challenges the status quo (Leifer & Mills, 1996). Unlearning is fundamental, as the entrenched routines and cognitive frameworks that once facilitated an organization's achievements may become rigid and resistant to transformation. This rigidity obstructs the organization's capacity to adopt new knowledge and innovations (Zaidi, 2023). Organizational learning theory posits that learning encompasses both the acquisition of new knowledge and the alteration or replacement of outdated knowledge structures that do not meet the organization's requirements (Joseph et al., 2023).

In the realm of SMEs, engagement in collaborative innovation endeavors with external partners introduces them to novel concepts, technologies, and methodologies. External partners, including suppliers, frequently present new perspectives and insights that may contradict the SME's established practices. Consequently, SMEs must actively participate in the unlearning process, which entails relinquishing outdated routines and embracing new practices that correspond with the novel knowledge introduced by these partners (Wong & Vongswasdi, 2024).

Furthermore, the theory of dynamic capabilities underscores the significance of reconfiguration, which involves modifying a firm's asset structure and transforming its operational capabilities to adeptly address new opportunities or threats. Joint innovation capabilities emerge from this reconfiguration process (Girod & Whittington, 2017). When SMEs participate in collaborative innovation, they not only gain new knowledge but also modify their existing capabilities to integrate this knowledge into their business operations (Rajapathirana & Hui, 2018). This reconfiguration frequently necessitates the relinquishment of obsolete skills and competencies rendered irrelevant by recent advancements (Henfridsson et al., 2009). An SME renowned for large-scale manufacturing may partner with a supplier to develop customized, high-quality products. In this context, the benefits of mass production, dependent on economies of scale, may become obsolete as customization and flexibility gain paramount importance (Kılıç & Atilla, 2024). Therefore, the SME must relinquish its current capabilities and obtain new ones that are more appropriate for personalized manufacturing.

The interaction of unlearning and reconfiguration is essential for the firm's dynamic capabilities, allowing it to adjust its strategies and operations in response to changing market demands influenced by collaborative innovation initiatives (Antunes & Pinheiro, 2020). These arguments highlight the beneficial correlation between collaborative innovation capabilities and organizational unlearning. As SMEs increasingly participate in collaborative innovation, it is imperative for them to abandon obsolete practices to effectively assimilate and utilize the new knowledge and capabilities acquired from these collaborations. Consequently, we put forth the subsequent hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1

There is a positive relationship between joint innovation capabilities and organizational unlearning for SMEs.

Organizational memory functions as a collective repository of an organization's historical data, safeguarding effective routines, procedures, and strategies (Megill, 1997). This memory offers stability and continuity, beneficial for maintaining consistency and efficiency, especially in repetitive tasks. In the realm of exploratory innovation, this stability can present both benefits and drawbacks (Lin et al., 2021). Organizational amnesia, on the other hand, refers to the inability to retain or effectively utilize knowledge, frequently leading to recurrent errors and inefficiencies. This memory loss may arise from elevated employee turnover, alterations in leadership, or insufficient knowledge-sharing systems. A robust organizational memory facilitates adaptation and innovation, whereas organizational amnesia hinders these processes, resulting in a cycle of relearning and setbacks (Shortt & Izak, 2021). Recent studies highlight that preserving organizational memory is essential to prevent the expensive repercussions of amnesia, especially in volatile business contexts (e.g., Leon et al., 2024).

Enduring organizational memory can result in cognitive and procedural inertia, thereby hindering an organization's ability to innovate. This inertia manifests in various forms, chiefly through the reinforcement of entrenched mental models and cognitive frameworks that impede employees from acknowledging the merit of innovative strategies (Moorman & Miner, 1997). For example, when an organization has previously achieved success with a specific strategy or process, there is a pronounced tendency to persist with those methods, even in the face of new and potentially disruptive innovations (Kuhlmann et al., 2023). This reliance on past accomplishments can significantly hinder an organization's capacity to adjust to evolving market dynamics and suppress creativity and innovation.

The retention of obsolete knowledge, combined with the acquisition of contemporary market expertise, may result in an excessive influx of information (Alshanty & Emeagwali, 2019;Cegarra-Navarro & Sánchez-Polo, 2007). This phenomenon, termed information overload, arises when the quantity of accessible information surpasses an organization's ability to process and comprehend it efficiently (Arnold et al., 2023). This overload presents considerable difficulties, especially in the exploration phase, where adaptability and swift adjustment are crucial. As organizational memory increases, it can elevate cognitive load, leading to protracted decision-making, overlooked opportunities, and a reduced ability to swiftly adjust to market changes (Laamanen et al., 2018).

Organizations must develop regenerative dynamic capabilities to address these challenges (Dixon et al., 2014). Regenerative dynamic capability denotes an organization's capacity to eliminate outdated knowledge and routines, consequently adopting innovative practices. The concept of unlearning is fundamental to this capability, allowing organizations to liberate themselves from the limitations of past experiences and adapt to new market realities. In the absence of the ability to unlearn, organizations may become ensnared in a cycle of diminishing returns, where entrenched practices no longer yield equivalent value, yet they resist adopting new strategies (Argote, 2012).

The significance of unlearning is amplified by the swift evolution of contemporary markets. Dougherty (1992) underscores that market knowledge can rapidly become obsolete, requiring ongoing renewal and adaptation of organizational knowledge. Organizations that excessively adhere to established knowledge jeopardize their competitive advantage by not adapting to market changes. Unlearning is essential for organizations to eliminate obsolete knowledge, thereby promoting collaborative sensemaking and improving information sharing throughout the organization (Cegarra-Navarro & Wensley, 2019). Organizations can enhance their capacity for innovation by updating their institutional knowledge to better align strategies with current market demands.

Furthermore, the capacity to unlearn is not only essential for organizational learning but also functions as a vital enabler of it. The unlearning process facilitates the cognitive capacity required for new learning to transpire (Klammer & Gueldenberg, 2019). When an organization actively participates in unlearning, it eradicates obsolete knowledge, thus facilitating the assimilation of novel ideas, methodologies, and practices. This dynamic is vital for cultivating a culture of ongoing learning and innovation, especially in rapidly evolving environments where adaptability is a must for sustaining a competitive advantage.

In conclusion, although organizational memory ensures stability and continuity, it may also obstruct innovation by fostering cognitive and procedural inertia, leading to information overload and reduced adaptability. Organizations must enhance their ability to unlearn, which is essential for fostering organizational learning and innovation. By participating in this vital practice, companies can refresh their knowledge base, improve their adaptability to changing conditions, and maintain a competitive edge in swiftly evolving markets. Consequently, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 2

There is a positive relationship between organizational unlearning and exploratory innovation for SMEs.

Within the context of SMEs, Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2 suggest that organizational unlearning is involved in the process of linking the capabilities of collaborative innovation and exploratory innovation. In order for SMEs to successfully utilize their external collaborations and achieve exploratory innovation, it is essential for them to engage in organizational unlearning. This is accomplished by fostering the fusion of knowledge (Argote, 2012), facilitating the development of cognitive ability (Klammer & Gueldenberg, 2019), overcoming challenges in adapting to changing market conditions (Moorman & Miner, 1997), and optimizing the value of collaborative innovation capabilities (Girod & Whittington, 2017). When it comes to transforming the potential of collaborative innovation capabilities into concrete innovative outcomes, mediation plays a vital role. This enables SMEs to maintain their competitiveness in markets that are constantly evolving. Therefore, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 3

Organizational unlearning mediates the relationship between joint innovation capabilities and exploratory innovation for SMEs.

Moderating role of the degree of internationalizationAs small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) expand their operations internationally, they confront increasingly intricate and varied market conditions. According to dynamic capabilities theory, firms must continuously adapt their resources and capabilities to effectively navigate these complex environments. However, this complexity often diverts attention from collaborative innovation capabilities, as firms become preoccupied with managing diverse regulatory frameworks, cultural disparities, and unique market circumstances (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000). This dispersion of focus can weaken the effectiveness of collaborative innovation capabilities in fostering organizational unlearning. As a result, SMEs may struggle to recognize and discard obsolete practices in favor of novel ones, leading to a potential weakening of the correlation between joint innovation capabilities and organizational unlearning as the level of internationalization rises (Hitt et al., 2012).

Dynamic capabilities theory further emphasizes the significance of resource reconfiguration to adapt to evolving environments. However, SMEs often operate with limited resources, which, upon internationalization, are frequently allocated to manage the complexities of various markets (Sui & Baum, 2014). This allocation reduces the focus on collaborative innovation and the process of organizational unlearning, as firms prioritize immediate operational efficiency over long-term innovation. Consequently, the redirection of resources and attention may undermine the connection between collective innovation ability and the unlearning process, as the essential skills required for unlearning might remain underdeveloped due to these resource constraints (Knight & Cavusgil, 2004).

Additionally, dynamic capabilities theory posits that organizations need to overcome resistance to change to effectively reconfigure their capabilities. However, the process of internationalization can exacerbate organizational inertia, as SMEs must maintain consistency and stability across multiple markets. This inertia fosters a reluctance to change, which hinders the firm's capacity to engage in unlearning, even when joint innovation capabilities are present (Zhang et al., 2022). The emphasis on maintaining stability in international operations can complicate the unlearning of existing routines and practices, thereby diminishing the positive correlation between joint innovation capabilities and organizational unlearning, particularly at higher levels of internationalization (Vermeulen & Barkema, 2002).

Furthermore, entering culturally and institutionally distant markets often necessitates dynamic capabilities that enable SMEs to adapt their joint innovation capabilities to new contexts. However, the challenges associated with transferring and adapting these capabilities across various markets can hinder organizational unlearning (Xi et al., 2020). SMEs may struggle to reconcile their existing practices with the new demands required in diverse international settings, leading to a weakened connection between collaborative innovation capabilities and organizational unlearning (Gaur et al., 2022).

As SMEs expand globally, they are also compelled to learn new practices and adapt to different market conditions, both of which are fundamental components of dynamic capabilities. However, the emphasis on acquiring new operational methods can paradoxically impede the process of abandoning old practices, particularly when those older practices have yielded success in the domestic market (Klammer et al., 2023). This simultaneous focus on learning new international practices while preserving effective domestic practices can create a paradox, where the necessity to absorb new knowledge hinders the ability to discard outdated knowledge (Erdogan et al., 2020). Consequently, this paradox can undermine the strong correlation between joint innovation capabilities and organizational unlearning, as the firm's focus shifts toward adapting to new markets rather than letting go of obsolete practices (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990).

In summary, the insights from dynamic capabilities theory and the challenges posed by internationalization suggest that as SMEs expand their global operations, a range of factors—including complexity, limited resources, cultural and institutional differences, organizational resistance to change, and the difficulties associated with learning and unlearning—contribute to a diminished positive correlation between joint innovation capabilities and organizational unlearning. These factors complicate the ability of SMEs to actively engage in organizational unlearning, even when they possess strong joint innovation capabilities. Thus, we propose that:

Hypothesis 4

The positive relationship between joint innovation capabilities and organizational unlearning is moderated by the degree of internationalization for SMEs.

According to dynamic capabilities theory, organizations must continually adapt their resources and capabilities to effectively respond to changing environments (Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997). However, in highly internationalized small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), the focus on managing the complexities of global operations can detract from the firm's ability to engage in organizational unlearning, which is a key factor for fostering exploratory innovation. As resources become stretched thin across multiple international markets, the processes necessary for unlearning—such as discarding outdated practices and experimenting with new ideas—may be deprioritized. This deprioritization can lead to a weakened relationship between unlearning and exploratory innovation (Novelo, 2015).

The increasing demand for resources to handle diverse regulatory environments, cultural differences, and market conditions can further limit the attention and capacity that SMEs have to engage in the deep unlearning processes required to drive exploratory innovation (Klammer et al., 2024). This shift in focus from innovation to operational efficiency and market adaptation reflects the challenges posed by internationalization, where the need to maintain day-to-day operations across varied contexts takes precedence over the longer-term goal of fostering innovation. As a result, the positive relationship between organizational unlearning and exploratory innovation becomes increasingly strained in highly internationalized firms (Hitt et al., 2012).

Moreover, the degree of internationalization often entails entering markets that are culturally and institutionally distant from the SME's home country. The greater the distance between the home and host countries, the more challenging it becomes to implement and benefit from organizational unlearning (Surdu & Narula, 2021). Unlearning is inherently disruptive, requiring organizations to question and discard established practices and cognitive frameworks. In international contexts, cognitive dissonance caused by cultural and institutional differences can exacerbate the challenges of unlearning, making it harder for SMEs to align their existing practices with new ones necessary for effective innovation in these diverse environments (Gaur et al., 2022).

When SMEs operate in culturally distant markets, they often struggle to reconcile their established practices with the new ones required for effective innovation. This difficulty in aligning organizational unlearning with diverse international practices further weakens the relationship between unlearning and exploratory innovation, particularly in SMEs that operate across multiple culturally and institutionally distant markets (Yoruk et al., 2021). The tension between maintaining established practices and adapting to new, unfamiliar environments often leads to a compromise that hinders the firm's ability to fully engage in the unlearning necessary for radical innovation.

As SMEs continue to internationalize, they tend to develop routines and practices aimed at ensuring stability and consistency across different markets. While these routines are essential for maintaining operational coherence, they can also lead to organizational inertia, making it difficult to implement the changes necessary for unlearning. Organizational inertia, defined as the resistance to change that organizations experience as they become more established (Hannan & Freeman, 1984), poses a significant challenge in highly internationalized SMEs. The need to maintain consistent operations across diverse markets can intensify this resistance, ultimately weakening the relationship between organizational unlearning and exploratory innovation. As firms become more focused on maintaining stability, they may neglect the experimentation required for new, potentially radical innovations (Vermeulen & Barkema, 2002).

Furthermore, internationalization often necessitates the learning of new practices and the adaptation to different market conditions. However, this focus on learning new international practices can paradoxically inhibit the process of unlearning old practices, particularly in SMEs that have experienced success in their home markets but now face the challenge of adapting to international contexts (Tran & Truong, 2022). The dual focus on learning new practices while maintaining successful home market practices creates a tension where the need to learn undermines the process of unlearning. This paradox can weaken the relationship between organizational unlearning and exploratory innovation, as SMEs struggle to balance the demands of adapting to new markets with the need to innovate through unlearning (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990).

In summary, the positive relationship between organizational unlearning and exploratory innovation is moderated by the degree of internationalization in SMEs. As these firms expand their operations internationally, various factors—including increased complexity, resource allocation demands, cultural and institutional barriers, organizational inertia, and the paradox of learning and unlearning—contribute to a weakening of this relationship. These challenges make it increasingly difficult for SMEs to effectively engage in the unlearning processes necessary to drive exploratory innovation, particularly in highly internationalized contexts. Insights from dynamic capabilities theory highlight the delicate balance that internationalized SMEs must maintain between operational stability and the pursuit of innovative breakthroughs through unlearning. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5

The positive relationship between organizational unlearning and exploratory innovation is moderated by the degree of internationalization for SMEs.

Based on the arguments presented, it can be predicted that there will be a moderated mediation process (Hayes & Rockwood, 2020). The correlation between the ability to innovate together and the ability to explore new ideas is affected by the level of internationalization. This acts as a contingency factor that moderates the indirect positive link through the process of unlearning within the organization, as suggested by Hayes (2018). Therefore, we propose that organizations with a high degree of internationalization exhibit a robust inverse correlation between joint innovation capabilities and exploratory innovation.

The suggested interaction suggests that the relationship between joint innovation capabilities and exploratory innovation through organizational unlearning is influenced by the combined effect of organizational unlearning and the level of internationalization. Greater levels of organizational unlearning, combined with lower levels of internationalization, strengthen the positive impact of joint innovation capabilities on exploratory innovation. Reduced levels of internationalization enhance the execution and utilization of organizational unlearning, leading to improved outcomes in exploratory innovation. Higher levels of internationalization may weaken the connection between joint innovation capabilities and exploratory innovation through organizational unlearning. Organizations with a high level of internationalization may encounter difficulties in effectively integrating joint innovative ideas into successful exploratory innovations.

We propose that the interaction acts as a moderator, influencing the indirect positive connection between joint innovation capabilities and exploratory innovation by strengthening organizational unlearning. This relationship is particularly pronounced at lower levels of interaction. We propose:

Hypothesis 6

The indirect positive relationship between joint innovation capabilities and exploratory innovation, mediated by organizational unlearning, is influenced by the level of internationalization in SMEs.

MethodsResearch designTo evaluate the interconnectedness depicted in Fig. 1, a sample of 450 logistics and general managers from the list of SMEs associated with a research group at a research-intensive university in the UAE was chosen and contacted. As a result of this initial screening, a total of 325 logistics/general managers chose to participate in this study. A total of 300 respondents were gathered from 150 enterprises situated in the emirates of Abu Dhabi, Dubai, and Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The participating companies range in size from 2 to 5000 full-time employees, with an average of 121 employees. Out of the total of 151 firms, 24 are engaged in the manufacturing sector, accounting for 16% of the total. The service industry is represented by 42 firms, making up 28% of the total. The retail sector has the highest number of firms, with 78 companies, constituting 52% of the total. The remaining 6 firms, which make up 4% of the total, operate in other industries. The mean firm age was 11.75 years; the youngest firm was merely one year old, while the oldest had been operational for 33.4 years.

The research team, which included a full-time research assistant, conducted data collection by visiting each SME to distribute the survey instruments. Data collection began in April 2018 and ended in September 2018. To ascertain the eligibility of the participants for our target demographic, initial contact was made via telephone. Subsequently, two sets of questionnaires, which served as the survey instruments, were distributed to each business. Throughout this period, the respondents were periodically contacted and prompted to finalize the survey. Both the general manager and a senior logistics manager employed within the enterprise were administered the same survey instrument. We obtained data from both of these respondent categories in order to avoid the issues typically linked to single-source bias (Zacca, Dayan, & Ahrens, 2015; Dayan et al., 2016). Joint innovation capabilities was assessed using data collected from logistic managers, as they were deemed to possess more objective and dependable information regarding these variables. The measurement of exploratory innovation, organizational unlearning, and the degree of internationalization was based on the responses provided by general managers. General managers were chosen for their macro perspective, which makes them more likely than logistic managers to have a broader view of the organization. The survey instruments were translated from English to Arabic by a native Arabic speaker who is also proficient in English. Subsequently, a different bilingual speaker translated the survey back into English. Subsequently, the research team and translators implemented the required modifications in accordance with the findings of Dayan et al.'s study (2016). Before collecting data, we carried out a sequence of preliminary tests. A group of twelve randomly chosen senior managers evaluated the substance and significance of the items. Afterwards, we reached out to four academics from relevant fields to obtain their feedback on the usability of the scale items. Subsequently, we made revisions to the questionnaires based on their comments. The procedures were conducted to guarantee the clarity and precision of the instruments (Dayan, Zacca, & Di Benedetto, 2013; Zacca, Dayan, & Ahrens, 2015).

MeasuresThe degree of Internationalization has been utilized as a measure to assess the extent to which businesses have expanded their operations internationally (Reuber & Fischer, 1997; Sullivan, 1994). Prior research in the context of SMEs has typically assessed the degree of internationalization using a single measure, specifically the ratio of a firm's export sales to its total sales (Ren et al., 2015). The excessively simplistic method of measuring the degree of internationalization was identified as a contributing factor to the inconsistencies observed in various studies within the field of international business literature (Pangarkar, 2008). We contend that the concept of internationalization is excessively intricate to be quantified by a solitary factor. Alternatively, it should be assessed using a framework that encompasses various dimensions of the level of internationalization. While previous studies (Reuber & Fischer, 1997; Sullivan, 1994) have developed constructs for the context of large multinational companies, these measures are not appropriate for SMEs (Genc et al., 2019). The rationale behind this is that certain components of the current frameworks may not be applicable to SMEs, especially in developing economies. For instance, inquiries related to foreign direct investment or the count of foreign staff may not be pertinent (Reuber & Fischer, 1997). In this study, a composite of certain elements from established constructs (Manolova et al., 2002; Ruzzier et al., 2007; Sullivan, 1994) that are relevant to the SME context were employed to assess various aspects of SME internationalization. The formative measurement items utilized to assess the degree of internationalization construct in our study encompass 1) the duration of internationalization; 2) the monetary value of exports; 3) the level of international experience possessed by management; 4) the extent of global vision; 5) the geographical separation between entities; 6) the proportion of foreign sales in relation to total sales (FSTS); and 7) the degree of import intensity.

We utilized ten reflective measurement items pertaining to three constructs to assess the proposed framework. These constructs were modified from established research to suit the UAE context. The measurement items for joint innovation capabilities were derived from Martin and Grbac (2003), whereas those for organizational unlearning and exploratory innovation were modified from Leal-Rodríguez et al. (2015) and He and Wong (2004), respectively. We utilized a five-point Likert-type scale for these assessments, with a rating of “1″ indicating “strongly disagree” and “5″ denoting “strongly agree.” A 5-point Likert-type scale was employed due to its user-friendliness and the presence of a neutral midpoint, enabling respondents to adopt a neutral position by selecting the 'Neither Disagree nor Agree (NDNA)' option. It is regarded as having an optimal balance between providing sufficient response options to enable significant distinctions in the responses and preventing excessive granularity that could result in confusion or response fatigue. The utilization of this prevalent 5-point Likert-type scale will enable subsequent research to compare their results and findings with this study. The Appendix includes a list of all reflective measurement items.

In order to isolate the effects of certain factors on the dependent variables (organizational unlearning and exploratory innovation), we employed control variables such as firm size, firm age, and venture life cycle. Based on previous research (e.g.,Sørensen & Stuart, 2000), which has found a connection between a company's age, its ability to collaborate on innovation, and its tendency to engage in exploratory innovation, the study controlled for the variable of firm age. Firm age was determined by calculating its natural logarithm. In order to isolate the impact of economies and diseconomies of scale (Bain, 1968), we adjusted the dependent variables for firm size, which was measured as the natural logarithm of total assets. We also accounted for the stage of the venture's life cycle. In order to consider the various stages of a venture's life cycle and mitigate any potential impacts, we requested the respondents to indicate the specific stage of their venture (startup, growth, maturity, or decline). To minimize the common method bias effect, we took measures to control the dependent variables for negative affectivity bias (Watson et al., 1988), which is not theoretically related to any of the variables used in our study. The items for the negative affectivity scale, with a rating scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), include the following statements: "Minor setbacks tend to irritate me too much", "I often get irritated at little annoyances", and "There are days when I am 'on edge' all of the time" (Yannopoulos et al., 2012). In line with Flynn, Pagell, and Fugate's (2018) approach, we aim to address common method bias concerns by incorporating the negative affectivity bias scale as a control variable.

Data analysesThe data analyses were performed using SmartPLS 4.1.0.3, a software developed by Ringle, Wende, and Becker in 2024. The hypotheses were evaluated through process procedure analyses utilizing 5000 bootstrapped samples. The analysis utilized bias-corrected and accelerated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) with centered variables, in accordance with the recommendations of Aiken and West (1991). The SmartPLS-Process was used to calculate bootstrapped confidence intervals (CIs) for evaluating the mediation effect (Hayes, 2018). Bootstrap methods are considered more effective than alternative tools, such as the Sobel test, for conducting mediation analysis. We performed a bootstrap analysis with 5000 iterations and bias-correlated estimates, as advised by Hayes (2018). The mediation effects were considered statistically significant if the confidence intervals (CIs) for both the lower and upper bounds did not include zero.

ResultsAssessment of common method varianceVarious methodologies were employed to tackle the problems associated with common method variance bias. To mitigate this bias, we utilized diverse data collection methodologies. To ensure the protection of personal information from unauthorized access, the survey required respondents to complete it anonymously from the very beginning. The survey questions clearly indicated that there is no definitive or incorrect response to these inquiries. To avoid any ambiguity, Podsakoff et al.(2003) advised against using questions that include multiple concepts or intricate language. After collecting the data, we assessed the existence of common method variance by employing various methodologies. Podsakoff et al. (2003) performed a comparative analysis of two measurement models using the partial least squares method. The initial measurement model included all features, while the subsequent model added an extra one. The statistics showed that the path coefficients were not statistically significant.

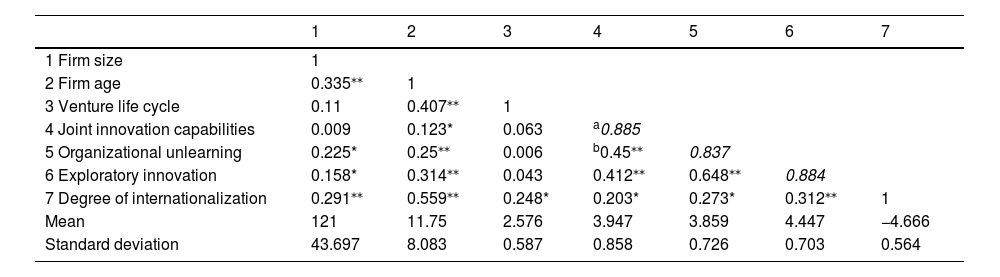

Construct validityTo assess convergent validity, the average variance extracted (AVE) value was determined by calculating the mean-squared loadings for the items on each scale. The minimum acceptable threshold for Average Variance Extracted (AVE) is 0.5. This value represents the extent to which the construct accounts for a minimum of 50% of the variability in the indicators on the scale, as specified by Fornell & Larcker in, 1981. The approach used in this study involved calculating the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio. The ratio in question functions as a measure of the relationships between all survey items, across various categories, in relation to the correlation among items that are classified as belonging to the same category. The HTMT values should be less than 0.85, indicating sufficient differentiation between the constructs, as recommended by Henseler et al., Ringle and Sarstedt (2015). The HTMT ratio analysis results (see Table 1) indicate that the data demonstrates satisfactory discriminant validity.

Together, these metrics offer ample evidence that a reflective measurement model, comprising four latent constructs, accurately represents the data. The reliability tests have confirmed that the model meets the criteria for item reliability, internal consistency reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Hence, the model possesses the capacity to address the aforementioned research inquiries. Afterwards, we utilized the variance inflation factor (VIF) to evaluate the existence of multicollinearity among the constructs, as recommended by Wilden et al. (2013). The VIF values for the reflective measures ranged from 1.086 to 1.743, which is well below the acceptable threshold of 5 (Hair et al., 2010). The results demonstrate that every variable has a high level of statistical significance, thereby confirming that the measurement model is well-suited for the data (Table 2).

Correlation table and descriptive statistics.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Firm size | 1 | ||||||

| 2 Firm age | 0.335⁎⁎ | 1 | |||||

| 3 Venture life cycle | 0.11 | 0.407⁎⁎ | 1 | ||||

| 4 Joint innovation capabilities | 0.009 | 0.123* | 0.063 | a0.885 | |||

| 5 Organizational unlearning | 0.225* | 0.25⁎⁎ | 0.006 | b0.45⁎⁎ | 0.837 | ||

| 6 Exploratory innovation | 0.158* | 0.314⁎⁎ | 0.043 | 0.412⁎⁎ | 0.648⁎⁎ | 0.884 | |

| 7 Degree of internationalization | 0.291⁎⁎ | 0.559⁎⁎ | 0.248* | 0.203* | 0.273* | 0.312⁎⁎ | 1 |

| Mean | 121 | 11.75 | 2.576 | 3.947 | 3.859 | 4.447 | −4.666 |

| Standard deviation | 43.697 | 8.083 | 0.587 | 0.858 | 0.726 | 0.703 | 0.564 |

Notes: n = 150.

Table 1 demonstrates the absence of multicollinearity, as none of the zero-order Pearson correlation coefficients surpasses the specified threshold 0.90. The relationship between organizational unlearning and exploratory innovation showed the strongest correlation (r = 0.648), followed by the correlation between organizational unlearning and innovation capabilities (r = 0.450). For all cases, these correlations are lower than the square root of the AVE (shown on the diagonal), thus confirming the distinctiveness of these constructs. The variable being studied, service innovation, shows moderate correlations with the main concepts of the research.

FindingsTable 3 presents the zero-order correlation coefficients and descriptive statistics of the study variables. On the other hand, Table 2 displays the mediation results produced by the SmartPLS-Process. Empirical evidence supports Hypothesis 1, as we discovered a robust and statistically significant positive relationship (β = 0.370, p < .001) between joint innovation capabilities and organizational unlearning. We gathered empirical evidence that confirms the connection between organizational unlearning and exploratory innovation (Hypothesis 2). This is evident in the significant and positive relationship we discovered (β = 0.524, p < .001). The indirect relationship between joint innovation capabilities and exploratory innovation, mediated by organizational unlearning, had a significant effect size of 0.194. The confidence interval [.119, 0.297] did not include 0, providing support for the mediation effect proposed in Hypothesis 3.

Mediation results (SmartPLS-Process).

| Organizational unlearning | Exploratory innovation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firm size | .000 | −0.000 | ||

| Firm age | .001 | .001 | ||

| Venture life cycle | −0.141 | −0.058 | ||

| Joint innovation capabilities | .370⁎⁎⁎ | .122* | ||

| Organizational unlearning | 0.524⁎⁎⁎ | |||

| R2 | .272 | .466 | ||

| Effect size | Bootstrap SE | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Indirect effect | .194 | .053 | .119 | .297 |

Notes: n = 150; SE = standard error; LLCI = lower limit confidence interval; UCLI = upper limit confidence interval.

In our theoretical discussions, we also hypothesized that the extent of internationalization has a negative moderating effect on the relationship between joint innovation capabilities and organizational unlearning (Hypothesis 4), as well as between organizational unlearning and exploratory innovation (Hypothesis 5). Table 4 shows that the joint innovation capabilities × degree of internationalization term has a negative, weak significant effect (β = −0.163, p < .10 [0.058]) on organizational unlearning. Additionally, the organizational unlearning × degree of internationalization term has a negative, moderate significant effect (β = −0.272, p < .05) on exploratory innovation. Based on the Process results, it was found that the connection between joint innovation capabilities and organizational unlearning became more pronounced at lower levels of the degree of internationalization. Specifically, the correlation coefficients were 0.442 at one standard deviation below the mean, 0.337 at the mean, and 0.231 at one standard deviation above the mean. This finding supports Hypothesis 4. Similarly, the correlation between organizational unlearning and exploratory innovation was found to be stronger when the degree of internationalization was lower. Specifically, the correlation coefficient was 0.625 at one standard deviation below the mean, 0.448 at the mean, and 0.270 at one standard deviation above the mean. These findings support Hypothesis 5. Fig. 2 and 3 shows a visual representation of this analysis.

Moderated mediation results (SmartPLS-Process).

| Organizational unlearning | Exploratory innovation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firm size | .001 | .001 | ||

| Firm age | .001 | .001 | ||

| Venture life cycle | −0.130⁎⁎⁎ | .057 | ||

| Joint innovation capabilities | .337⁎⁎⁎ | .103* | ||

| The degree of internationalization | .131 | .124 | ||

| Joint innovation capabilities × the degree of internationalization | −0.163+ | |||

| Organizational unlearningOrganizational unlearning × the degree of internationalization | .448⁎⁎⁎−0.272* | |||

| R2 | .101 | .173 | ||

| Conditional direct effect of joint innovation capabilities on organizational unlearning | ||||

| Effect size | Bootstrap SE | LLCI | ULCI | |

| −1 SD | .442 | .111 | .244 | .612 |

| Mean | .337 | .076 | .217 | .467 |

| +1SD | .231 | .090 | .113 | .419 |

| Conditional direct effect of organizational unlearning on exploratory innovation | ||||

| Effect size | Bootstrap SE | LLCI | ULCI | |

| −1 SD | .625 | .097 | .460 | .778 |

| Mean | .448 | .091 | .306 | .605 |

| +1SD | .270 | .148 | .044 | .530 |

| Conditional indirect effect of joint innovation capabilities on exploratory innovation | ||||

| Effect size | Bootstrap SE | LLCI | ULCI | |

| −1 SD | .276 | .074 | .164 | .412 |

| Mean | .151 | .048 | .085 | .251 |

| +1SD | .061 | .046 | .011 | .178 |

Notes: n = 150; SE = standard error; LLCI = lower limit confidence interval; UCLI = upper limit confidence interval.

A direct test was conducted to examine the proposed moderated mediation dynamic (Hypothesis 6). This dynamic suggests that the extent of internationalization weakens the role of organizational unlearning in explaining the relationship between joint innovation capabilities and exploratory innovation (Hayes, 2018). The results showed that the strength of the indirect relationship between joint innovation capabilities and exploratory innovation decreased as the degree of internationalization increased. More precisely, the indirect effects varied from 0.276 when the moderator was one standard deviation below the average, to 0.151 at the average, to 0.062 when the moderator was one standard deviation above the average. The confidence intervals (CIs) for the degrees of internationalization did not encompass the value of 0 at all levels ([.164; 0.412; for one standard deviation below the mean], [.085; 0.251; at the mean], and [.011; 0.178; one standard deviation above it]).

The level of internationalization reduced the positive indirect connection between joint innovation capabilities and exploratory innovation, due to organizational unlearning. This finding supports Hypothesis 6 and aligns with our overall conceptual framework.

DiscussionsTheoretical contributionsThis study responds to the numerous calls for future research on the internationalization of SMEs in emerging economies (e.g., Du et al., 2023; Genc et al., 2019). While SMEs are catalysts for economic growth, particularly in emerging markets, their contribution to value added is relatively limited. The lack of innovation in SMEs relative to large corporations may be a significant factor contributing to this issue. Therefore, enhancing the innovation performance of SMEs is critical for both these enterprises and the economies of emerging nations (Hilmersson et al., 2023). Conversely, internationalization has proliferated among SMEs, attributed to advancements in communication technologies and reduced transportation costs. In emerging markets, SMEs are progressively engaging in international activities daily, aided by government support (Pastelakos et al., 2023).

Despite the research regarding the relationship between internationalization and innovation (e.g., Evers et al., 2023; Hilmersson et al., 2023), the specific dynamic capabilities that firms cultivate through their internationalization endeavors, which subsequently enhance their innovative capacity, remain ambiguous. Understanding these generative mechanisms requires analyzing the mediators and moderators essential for enhancing the impact of joint innovation capabilities on the exploratory innovation performance of SMEs during their internationalization process. These mechanisms have significant business implications concerning the role of internationalization in generating innovative outcomes. We investigate this gap by inquiring: What mechanisms enable firms to transform their collaborative innovation capabilities into tangible innovation outcomes? The response to this inquiry holds considerable consequences for SMEs in developing markets. This study modeled the degree of internationalization as a moderator in the relationship among joint innovation capabilities, organizational unlearning, and exploratory innovation. Subsequently, we evaluated the proposed model within the framework of an emerging market, specifically the United Arab Emirates.

First of all, the results of this study offer important insights into the interconnectedness between a firm's innovation capacity, the process of organizational unlearning, the exploration of novel innovations, and the degree of internationalization within SMEs. Together, these findings shed light on how these factors interact to shape innovation outcomes in SMEs. This understanding not only clarifies the dynamics at play but also extends existing research on dynamic capabilities, organizational unlearning, and internationalization. Previous studies have highlighted the importance of dynamic capabilities in driving innovation and competitive advantage (e.g., Pang et al., 2023; Robertson et al., 2023), while the role of organizational unlearning has been emphasized as a necessary precursor to embracing new knowledge and practices (Kyrdoda et al., 2023). By linking these processes with SMEs' international activities, this study enriches the internationalization literature, suggesting that firms capable of unlearning outdated routines and fostering innovation are better positioned to navigate global markets and pursue new opportunities. This reinforces prior research that underscores the need for organizational flexibility and the ability to adapt to rapidly evolving global business environments e.g., Anand et al., 2024).

The results of this study align closely with dynamic capabilities theory, which underscores the significance of a firm's capacity to integrate, develop, and reconfigure internal and external resources to adapt to swiftly evolving environments (Teece et al., 1997). Notably, this research highlights the significant relationship between innovation capabilities and the process of organizational unlearning, particularly within SMEs. This aligns with prior studies that have pointed to the critical role of dynamic capabilities in allowing SMEs to continuously adapt and realign their knowledge resources to maintain a competitive edge, especially when engaging in collaborative innovation (Zahra et al., 2006). The concept of organizational unlearning emerges as a key element within the dynamic capabilities framework, as it involves shedding outdated routines and practices to accommodate new knowledge, thereby stimulating innovation. Recent studies endorse this perspective, indicating that the capacity to unlearn is essential for promoting organizational renewal and maintaining agility in response to evolving market demands (Klammer et al., 2024, 2023).

This study shows that organizational unlearning mediates joint innovation capabilities and exploratory innovation using dynamic capabilities theory. This mediating role suggests that unlearning is a proactive dynamic capability that helps SMEs optimize collaborative innovation. Discarding outdated knowledge helps SMEs absorb and integrate new insights from external partnerships, enabling transformative exploratory innovations. This finding highlights unlearning as a critical process that supports organizational resource adaptation and reconfiguration, which helps explain how dynamic capabilities work in SMEs, particularly in innovation. It supports Eisenhardt and Martin ((2000)), who argue that firms need dynamic capabilities like unlearning to compete in fast-changing environments. Previous research suggests that unlearning helps firms innovate by allowing them to break from routines and adopt new knowledge (Zahra et al., 2006). Unlearning helps SMEs leverage joint innovation capabilities, making it an essential innovation mechanism, according to this study.

Moreover, this study investigates the impact of internationalization on unlearning and exploratory innovation, offering a novel viewpoint on organizational unlearning. The results indicate that international operations may influence the innovation-enhancing capacity of unlearning. The challenges of managing diverse international markets—aligning with various institutional frameworks and satisfying market demands—can diminish the innovation advantages of unlearning. The influence of unlearning on innovation is contingent upon the context. Tsang and Zahra (2008) assert that contextual factors, such as the firm's environment and its capacity to adapt to external pressures, influence unlearning outcomes. Internationalization amplifies organizational complexity, complicating the process of unlearning as firms must relinquish obsolete knowledge and assimilate new, diverse perspectives across various markets (Klammer et al., 2024). These findings underscore the significance of context in unlearning, particularly in international environments where adaptation difficulties may hinder innovation.

In addition, this study examines how internationalization levels affect SME joint innovation, organizational unlearning, and exploratory innovation. Internationalization complicates innovation because firms must adapt to different cultural, regulatory, and market environments. While SMEs expand globally, internationalization weakens the positive link between joint innovation capabilities and organizational unlearning, making external knowledge integration harder. Previous research has shown that multinational companies struggle to manage knowledge across contexts. International markets' diverse knowledge sources make unlearning outdated practices and integrating new knowledge harder for firms, according to Prange and Pinho (2017). Hitt, Tihanyi, Miller, and Connelly (2006) suggest that cross-border operations complicate knowledge transfer, limiting firms' unlearning and innovation. These studies show that internationalization provides access to more external knowledge, but the added complexity can hinder unlearning, affecting SMEs' innovation capabilities.

Furthermore, the correlation between organizational unlearning and exploratory innovation decreases in internationalized SMEs, according to this study. This result improves internationalization research by revealing the trade-offs firms face when expanding globally while maintaining innovation. It suggests that international operations' complexity may reduce unlearning's benefits, limiting a company's exploratory innovation. The internationalization process model (Johanson & Vahlne, 2015) shows that firms gradually improve their ability to navigate international expansion, despite transient disruptions in unfamiliar markets. Internationalization requires companies to learn, which may slow innovation in the short term (Casillas & Moreno-Menéndez, 2014). Thus, while companies may overcome these challenges, the initial complexities of managing different markets can reduce the innovation benefits of organizational unlearning.

In conclusion, this study offers significant insights into the relationship among dynamic capabilities, organizational unlearning, and internationalization. It underscores the significance of organizational unlearning as a dynamic capability that empowers SMEs to optimize their collaborative innovation endeavors for exploratory innovation. Simultaneously, it underscores the intricacies introduced by internationalization, which may diminish the interrelations among these fundamental components. These findings indicate that SMEs must meticulously evaluate the interplay between their innovation capabilities, unlearning processes, and international expansion strategies to enhance their innovation outcomes. This study enhances theoretical comprehension of these dynamics and provides practical insights for SMEs seeking to address the challenges of innovation in a globalized market.

Managerial implicationsThe results of this study have significant implications for managers of SMEs who are interested in improving their innovation outcomes through joint innovation capabilities, organizational unlearning, and internationalization strategies.

The correlation between joint innovation capabilities and organizational unlearning implies that SMEs should actively pursue partnerships with external collaborators to create a favorable environment for discarding outdated knowledge and practices. Managers ought to give priority to strategic partnerships that question the existing state of affairs and promote the adoption of fresh viewpoints and methods. SMEs can preserve a dynamic and flexible organizational culture, which is crucial for remaining competitive in rapidly evolving markets. For instance, establishing partnerships with cutting-edge start-ups or research institutions can offer the external input necessary for successful unlearning and subsequent innovation.

The discovery that the process of unlearning within an organization has a positive impact on exploratory innovation emphasizes the significance of establishing a corporate culture that places importance on ongoing learning and the readiness to discard outdated practices. Managers ought to allocate resources towards training programs that promote critical thinking and the challenging of established routines, thereby fostering an environment conducive to innovation. Creating a secure environment that encourages employees to freely explore new ideas without the fear of failure is essential for promoting exploratory innovation. This type of innovation is particularly important for SMEs that want to distinguish themselves in the market (Lecuona & Reitzig, 2014).

The study demonstrates that organizational unlearning acts as a mediator between joint innovation capabilities and exploratory innovation. This suggests that unlearning plays a decisive role in transforming collaborative efforts into tangible innovation outcomes. Managers must understand that merely investing in joint innovation activities is not enough; they must also proactively oversee the process of unlearning within their organizations in order to fully reap the advantages of these collaborations. One possible approach is to establish systematic procedures for evaluating and eliminating obsolete information, while also fostering a receptive attitude towards innovation and novel concepts.

The results also indicate that the level of internationalization influences the connections between joint innovation capabilities, organizational unlearning, and exploratory innovation. More precisely, these connections become less strong as the level of internationalization increases. This suggests that SMEs that operate in highly globalized environments encounter extra difficulties in effectively managing the process of unlearning and innovation. Managers in SMEs should be cognizant of the intricacies brought about by internationalization, including varied cultural norms and regulatory environments, which can hinder the process of unlearning (Hitt et al., 2006). In order to address these difficulties, SMEs should contemplate implementing more region-specific innovation strategies or allocating resources to cross-cultural training in order to effectively handle the incorporation of diverse knowledge sources.

Considering that the correlation between joint innovation capabilities and exploratory innovation through organizational unlearning becomes less significant as the level of internationalization increases, SMEs should customize their innovation strategies according to their degree of international exposure. For example, SMEs that have a strong global presence could gain advantages by creating stronger systems for combining knowledge and improving communication across different cultures. This would help reduce the risk of losing valuable knowledge during the process of unlearning (Vahlne & Johanson, 2017). However, SMEs that have not expanded internationally may prioritize utilizing their collaborative innovation abilities to promote unlearning and subsequent innovation, without the additional complications of managing international operations.

For SMEs that have a significant presence in international markets, it can be advantageous to create tailored strategies that tackle the distinct obstacles associated with operating in multiple markets. One approach could be to establish decentralized innovation hubs that specifically target regional markets. Another option is to form specialized teams that are dedicated to managing the processes of unlearning and innovation in various cultural contexts. By doing this, SMEs can more effectively match their innovation efforts with the varied requirements of their global markets. As a result, they can optimize the influence of their collaborative innovation capabilities and processes of unlearning.

Limitations and directions for future researchThis study highlights the interconnections between joint innovation capabilities, organizational unlearning, exploratory innovation, and internationalization in SMEs. However, it faces several limitations that must be addressed to enhance the generalizability and applicability of its findings.

One significant limitation is that the socio-economic, cultural, and regulatory conditions of the Middle East may constrain the study's generalizability to this region. Local customs, religious beliefs, and government policies heavily influence business practices in the Middle East, meaning that innovation strategies that work in Western contexts may not be applicable here. Therefore, future research must take these contextual differences into account when attempting to apply the study's findings to the Middle Eastern environment.

Additionally, the impact of internationalization on SMEs in the Middle East, particularly in the UAE, may differ significantly from the dynamics observed in other regions. While the UAE serves as a hub for global trade and benefits from political and economic stability, internationalization is not a uniform process. SMEs in politically unstable areas may face more challenges, leading to varied outcomes in terms of innovation and organizational unlearning. Hence, the influence of internationalization on innovation in the Middle East is likely to vary based on the political and economic conditions of individual countries. Future research must, therefore, explore these differences by examining how international exposure and market conditions influence innovation and unlearning in Middle Eastern SMEs.

Another important factor is the diverse nature of innovation ecosystems across the Middle East, which complicates the application of study results to the region as a whole. For instance, while the UAE benefits from advanced infrastructure and government support for innovation, other countries in the region may lack the resources and institutional backing required for innovation. These disparities in innovation ecosystems suggest that joint innovation capabilities, unlearning, and internationalization will interact differently across the region, making it imperative for future research to investigate these variations to fully understand their impact.

Furthermore, the challenge of transparency and data availability in the Middle East poses additional hurdles for research. The cultural inclination to avoid discussing failures or challenges may skew self-reported data, particularly when examining concepts like organizational unlearning and innovation. This bias could compromise the accuracy of the study's conclusions. To address this issue, future research should employ multiple data sources and methodologies to cross-verify findings and reduce the potential biases associated with self-reported data.

The use of cross-sectional study designs is another limitation, as this approach collects data at a single point in time. While such designs can highlight correlations between variables, they cannot explain causal relationships or track changes over time. Longitudinal studies are necessary to capture the temporal dynamics of joint innovation capabilities, organizational unlearning, and exploratory innovation, particularly as SMEs engage in international expansion. These longitudinal approaches will provide a more nuanced understanding of how these variables evolve over time.

The study's assessment of internationalization may also be overly simplistic, as it fails to account for the cultural, regulatory, and market diversity inherent in international activities. Internationalization involves more than just geographic expansion; it also encompasses adapting to varied cultural norms and regulatory landscapes. Therefore, the study's methodology may overlook these essential dimensions, limiting its ability to fully capture how internationalization affects the relationships between innovation and unlearning. Future research should adopt more comprehensive internationalization metrics to account for these complex factors.